Business Research Methods

advertisement

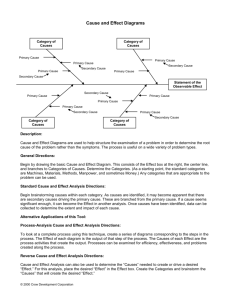

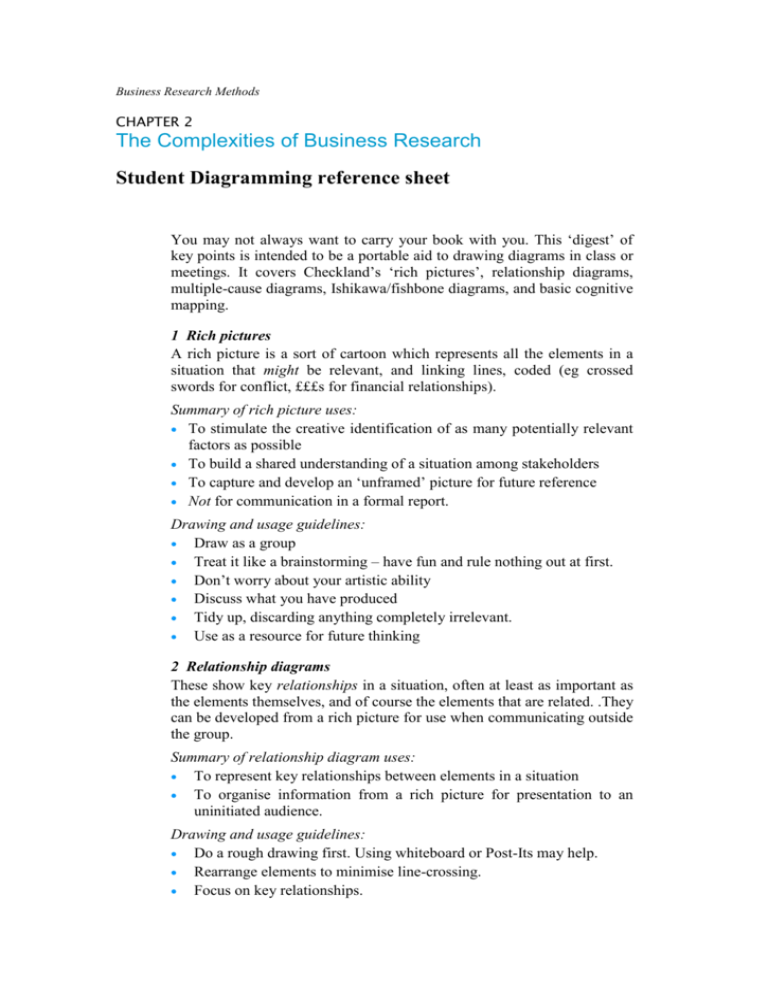

Business Research Methods CHAPTER 2 The Complexities of Business Research Student Diagramming reference sheet You may not always want to carry your book with you. This ‘digest’ of key points is intended to be a portable aid to drawing diagrams in class or meetings. It covers Checkland’s ‘rich pictures’, relationship diagrams, multiple-cause diagrams, Ishikawa/fishbone diagrams, and basic cognitive mapping. 1 Rich pictures A rich picture is a sort of cartoon which represents all the elements in a situation that might be relevant, and linking lines, coded (eg crossed swords for conflict, £££s for financial relationships). Summary of rich picture uses: To stimulate the creative identification of as many potentially relevant factors as possible To build a shared understanding of a situation among stakeholders To capture and develop an ‘unframed’ picture for future reference Not for communication in a formal report. Drawing and usage guidelines: Draw as a group Treat it like a brainstorming – have fun and rule nothing out at first. Don’t worry about your artistic ability Discuss what you have produced Tidy up, discarding anything completely irrelevant. Use as a resource for future thinking 2 Relationship diagrams These show key relationships in a situation, often at least as important as the elements themselves, and of course the elements that are related. .They can be developed from a rich picture for use when communicating outside the group. Summary of relationship diagram uses: To represent key relationships between elements in a situation To organise information from a rich picture for presentation to an uninitiated audience. Drawing and usage guidelines: Do a rough drawing first. Using whiteboard or Post-Its may help. Rearrange elements to minimise line-crossing. Focus on key relationships. Label your diagram clearly. It is useful as adiagnostic tool. It can help identify relevant systems. It may also be useful later to check the likely impact of changes. 3 Multiple-cause diagrams These are used to explore the ‘Why?’ of a situation. Why does the problem exist? What is causing it? Wicked problems or messes usually involve many causes which together bring the situation about. Multiplecause diagramming can stop you assuming a ‘single cause’ and help you understand different levels of underlying causal factors. The elements in a multiple-cause diagram are the event or situation you are investigating (this is often circled to distinguish it), phrases representing events or states that contribute to the causation of that situation or to other causal factors, and arrows. An arrow pointing from event A to event B means that event A causes or contributes to event B. Summary of multiple-cause diagram uses: To explore the factors causing or contributing to an issue To find root causes. Multiple-cause diagrams can be used individually, in interviews or by groups. Note: diagrams are always drawn backwards from the issue in question. Drawing and usage guidelines: Identify the situation you want to explore. Write this in a blob. Ask why is this happening – look for all the contributory causes. Draw an arrow from each to your blob.. Take each causal factor in turn and ask what might be causing that. Join these causes to the relevant causal factor. Repeat until you have all the factors involved. Check that your arrows point toward the thing being caused – it is easy to reverse the logic by accident. Label your diagram clearly. Use it to ensure that you – or a team – understand the underlying causes of an issue. Use it in an interview to ensure that you have elicited the underlying causes of an issue from an informant. 4 Cause-and-effect or Ishikawa/fishbone diagrams In contrast to a multiple-cause diagram which explores existing causes, an Ishikawa or fishbone diagram seeks to capture all possible causes. It is commonly used in quality management. Each major ‘bone’ represents a type of error or quality fault, with subsidiary bones showing factors which might contribute to or cause these (as shown in the following example [slide]). Fishbone diagrams are useful in suggesting what data to look for. Summary of the key uses of Ishikawa diagrams: To identify possible causes of faults To guide future thinking To indicate what data may be needed. Drawing and usage guidelines: Work from logical possibilities rather than using only actual data. Involve those who fully understand the process in question. Keep the diagram tidy. Label your diagram clearly. 5 Cognitive mapping Cognitive mapping refers to a variety of approaches to attempting to represent cognitive structures, or people’s tacit theory, as part of a group’s exploration of an aspect of an issue, or as an interviewing technique. Typically, cognitive maps seek to represent and link ideas that people are using, and often also to arrange them in a hierarchy. Multiple-cause diagrams are a very simple example of a cognitive map, but you might wish to map perceived causes and effects, show different sorts of effects, and use a variety of symbols to distinguish (for example) positive from negative effects. Summary of cognitive mapping uses: To help the researcher structure his/her initial thinking To surface, structure and analyse ideas during an interview or workshop To analyse qualitative data after it is collected To communicate findings in a report. Drawing and usage guidelines: Decide on the purpose for your diagram. Provide a key to any symbols used. Use cognitive mapping with either individuals or groups. Ensure that interviewees and groups understand the process. Use for surfacing assumptions and tacit theory. Final checklist for any diagram Is it clearly titled? Is it clear what all symbols indicate? Is the diagram uncluttered enough for its message to be clear? Yes/No