April 21, 2011

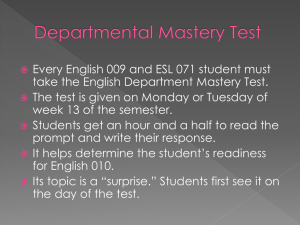

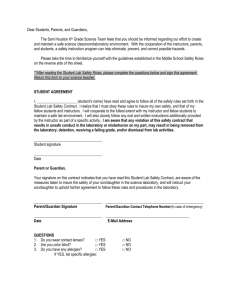

advertisement