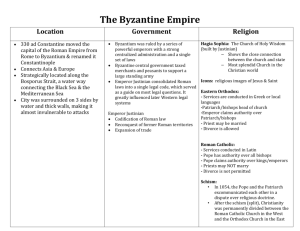

THE BREAK BETWEEN THE ROMAN AND BYZANTINE CHURCHES

advertisement

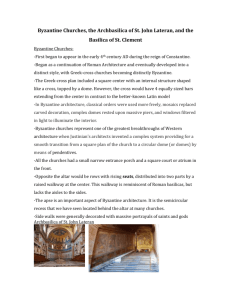

THE BREAK BETWEEN THE ROMAN AND BYZANTINE CHURCHES As Western Europe and the Byzantine Empire became more and more isolated from each other, differences between the Christian religious practices of Rome and Constantinople increased. Romans said their religious services in Latin; the Byzantines used Greek. Roman priests were clean-shaven and were expected not to marry; Byzantine priests were bearded and often married. Roman bishops were supposedly free from secular (political) control; Byzantine patriarchs were considered state officials, and head of the church in Byzantium, the patriarch of Constantinople, was appointed by the emperor himself. Byzantine emperors bitterly resented the alliances of the popes with the Frankish rulers, whom they considered their inferiors in rank, power, and culture. They also resented, and strongly resisted, the attempts of the popes in distant Rome to regulate a church that in Byzantium was looked upon as a part of the government. THE ICONOCLASTIC CONTROVERSY, 726 – 843 During the reign of the Byzantine Emperor Leo III (emperor 714-741), a dispute over theology drove the popes and patriarchs further apart. Leo, a devout but practical man, was worried by two developments in the church: the growing wealth of the monasteries, whose monks, landholders as they were, opposed his efforts to reform the system of landowning; and the increasing veneration of icons (sacred paintings or statues), which he feared would lead to paganism. His efforts to reduce the power of the monks and to rid the church of icons led to a major struggle between the church and state called the “Iconoclastic Controversy.” In 726 Leo ordered the destruction of all icons in the churches and monasteries, and his followers enthusiastically rushed around smashing statues and earning the name “Iconoclasts” (image-breakers). Many monks and priests, eager to defend both their beloved icons and their property rights, opposed the Iconoclasts. The pope, who favored icons, excommunicated Leo, denied him the right to take part in religious services, and declared him and his followers to be heretics. The struggle over icons that Leo had begun continued for more than a century after his death. It was not until 843 that the Emperor Michael III (emperor 842-867) admitted defeat and allowed the icons to be restored to Byzantine churches. The controversy left the eastern and western Christians more divided than they had been, for most western Europeans had supported the popes, while many Byzantines had supported their emperors. THE SEPARATION OF THE ORTHODOX AND CATHOLIC CHURCHES, 1054 During the two centuries after the end of the Iconoclastic Controversy, the Byzantine Empire enjoyed its greatest power and cultural achievement, and its church leaders shared the power and self-confidence of the emperors. At the same time western Europe was divided among weak, poverty-stricken, and often short-lived kingdoms, and church leaders there were frequently occupied in resolving disputed among themselves over matters of faith and church government. Not surprisingly, differences between eastern and western Christians became ever greater. In 1054 the pope sent a legate (representative) to Constantinople. Largely as a result of political and cultural differences (although supposedly because of a dispute over the nature of the Trinity), the papal legate and the patriarch of Constantinople excommunicated each other. After this event the Roman and Byzantine churches drifted so far apart that their separation was generally taken for granted; although it was not so regarded at the time, 1054 later came to be accepted as the definite date of the schism (split). After the schism, the church of the Byzantines called itself the Orthodox Church. Reflecting the Greek Byzantine tradition in its language and forms of worship, it was tied closely to the Byzantine government and was headed by the patriarch of Constantinople. The Roman Catholic Church, using the Latin language of ancient Rome and headed by the Roman pope, continued to dominate the religious life of western Europe. Each church considered itself to be the true heir of the pure Christian tradition, catholic in the sense that it included all true Christians and orthodox in the sense that its beliefs truly reflected Christ’s teachings. Whatever the merits of the claims of each church, one fact was certain: the Christian Church, like the old Roman Empire, had divided into two different and often hostile parts.