Accuracy of Self-Report of Pregnancy Smoking in a Southern

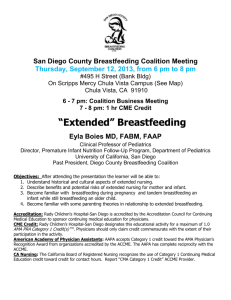

advertisement

1 Breastfeeding Initiation in a Rural Sample: Predictive Factors and the Role of Smoking Beth A. Bailey, PhDa, Heather N. Wright, BSb a Associate Professor of Family Medicine, Quillen College of Medicine, East Tennessee State University; nordstro@etsu.edu b Medical Student, Quillen College of Medicine, East Tennessee State University; hwright28@gmail.com Please send all correspondence to Dr. Beth Bailey at: P.O. Box 70621, Johnson City, TN 37614 Phone: (423)439-6477; Fax: (423)439-2440 Dr. Bailey is a Developmental Psychologist with a research background in behavioral teratology and pregnancy health behaviors. She is director of the Tennessee Intervention for Pregnant Smokers (TIPS) Program, a prenatal initiative to improve birth outcomes in Tennessee. Ms. Wright is a second year medical student who was a member of the TIPS Program staff. She is interested in maternal child health issues and in rural medicine. Funding: Provided by the Tennessee Governor’s Office on Children’s Care Coordination Summary Statement: This study examined factors that predict breastfeeding in a rural sample with low rates of breastfeeding initiation. Initiation was associated with older age, higher levels of education, private insurance, non-smoking and non-drug using status, and primiparity, with current smoking the single strongest predictor of failure to breastfeed after control for confounding. Findings can inform interventions and also point to the need for education emphasizing that breastfeeding is not contraindicated even if a mother continues to smoke. 2 Abstract The study objective was to identify demographic, medical, and health behavior factors that predict breastfeeding initiation in a rural population with low breastfeeding rates. Participants were 2,323 women who experienced consecutive deliveries at two hospitals, with data obtained through detailed chart review. Only half of the women initiated breastfeeding, which was significantly associated with higher levels of education, private insurance, nonsmoking and non-drug using status, and primiparity after control for confounding. Follow-up analyses revealed that smoking status was the single strongest predictor of failure to breastfeed, with non-smokers nearly twice as likely to breastfeed as smokers, and those who had smoked a pack per day or more the least likely to breastfeed. Findings reveal many factors placing women at risk for not breastfeeding, and suggest that intervention efforts should encourage a combination of smoking cessation and breastfeeding while emphasizing breastfeeding is not contraindicated even if the mother continues to smoke. Keywords: breastfeeding initiation, smoking, failure to breastfeed 3 Introduction Over the past 15 years, the rate of breastfeeding initiation in the United States has increased from 60% of infants born in 1993 to 74% of infants born in 2008.1 Despite this trend, regional variations exist. The northwestern states exhibit the highest rates of initiation, but rates are still disparately low for women living in the southeastern United States.2 The CDC Breastfeeding Report Card analyzed breastfeeding rates and “friendliness” toward breastfeeding for every state.1 In the 2009 report, the seven lowest rates of initiation were all in southeastern and/or Appalachian states (KY, TN, WV, OH, MS, LA, AL), and together these states had an average initiation rate of 55%.1 This discrepancy (adjusted odds of not being breastfed 2.5-5.15 times greater) exists even after controlling for sociodemographic factors. 2 Additionally, when states were grouped based on a number of indicators of “friendliness” toward breastfeeding, including presence of La Leche League groups, breastfeeding coalitions, and state legislation regarding breastfeeding in public places, these seven states were in the lowest quartile.1 The benefits of breastfeeding for maternal and child health have been well documented, 312 and the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the World Health Organization all recommend exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life.13-15 Research studies have revealed a number of factors related to breastfeeding initiation and point to those women most likely to breastfeed. Actual initiation of breastfeeding, regardless of intent during prenatal care, is consistently related to many background factors. For example, it is well documented that as maternal age16,17 and years of education 18-21 increase so does the likelihood of breastfeeding. Findings regarding other associated factors are somewhat less consistent across studies. Being married2,18-20 and higher socioeconomic class2,21 are both usually associated with a higher likelihood of breastfeeding. 4 Prenatal care advice and the availability of resources like LeLeche League tend to influence a mother’s decision to breastfeed,22 and may play a role in the regional differences in breastfeeding that have been observed.1 Racial differences in breastfeeding initiation exist, however, results are inconsistent.21 For example, many investigators have found that Caucasian and Asian mothers have the highest rates of breastfeeding2 while others have found that Hispanics are more likely to breastfeed.23,24 African Americans often show low breastfeeding rates,2,20 but a handful of studies have found African American mothers to be more likely than Caucasians to breastfeed.20,23,25 Confounding factors, including education level and other socioeconomic variabilities, likely play a role in these discrepancies. Infant health at delivery may encourage or discourage breastfeeding—results are mixed. Babies who require intensive care admission may be more difficult to breastfeed; however, having a baby with health problems may make a mother more motivated to breastfeed, especially if she believes it will improve the infant’s health.26,27 Smoking and the use of other substances has also been found to be associated with breastfeeding decisions. Several reports have suggested that women who smoke are significantly less likely to initiate and continue breastfeeding than those who do not smoke.21,28 A population-based study in Oregon revealed that non-smokers were twice as likely as smokers to be exclusively breast feeding at two weeks post-partum.29 A population-based study in Canada also found that women who smoked were half as likely to initiate breast feeding as non-smokers.30 Clinically-based studies have also found significantly decreased rates of breastfeeding initiation among smokers.16,17,19,31 In addition, several recent comprehensive reviews of the literature have concluded that maternal smoking status is a significant and consistent predictor of failure to breastfeed, 5 even after control for confounding demographic factors, and that overall smokers are 15% to 40% more likely to formula feed than non-smokers.21,28,32 Finally, women who drink alcohol heavily, and those who use illicit substances have also been found to be less likely to initiate breastfeeding than those who do not.21,30,33 The aim of the current study was to evaluate demographic, medical, and health behavior factors that predict breastfeeding initiation in a sample of women from rural Southern Appalachia with suspected low rates of breastfeeding initiation and known high rates of smoking during pregnancy.34,35 Of particular interest was the potential role of maternal smoking in the decision to begin breastfeeding in this population. Methods Participants Eligible study participants were all women who gave birth in two hospitals in Southern Appalachia between January 1, 2006 and December 31, 2007. The first hospital was the sole delivery hospital in the county, serving that county as well as women from several neighboring counties without delivery services. The second hospital was the largest of three delivery hospitals in a nearby county, serving women residing in that county and from over a dozen counties with and without delivery services. During the study period, 2556 women delivered infants who survived to nursery assignment at the target hospitals. Inaccuracies in the recording of medical record numbers (which precluded collection and match up of all data of interest in the study) reduced the sample size to 2403. Missing data on the primary variables of interest (feeding choice and smoking status) further reduced the final sample size to 2323, representing over 90% of all deliveries in the two hospitals during the study period. 6 Measures and Methods The study and all procedures were approved by the affiliated university Institutional Review Board and the hospital system research department. Data of interest were obtained through detailed chart review. Maternal delivery charts, complete prenatal charts, and corresponding newborn hospital charts were reviewed by three trained research staff members. The initial 2% of charts were reviewed by all three staff members, and inter-rater reliability for all variables of interest exceeded 98%. Consequently, the remaining charts were each reviewed by a single examiner, with any concerns about variable recording that arose brought to the principal investigator for resolution. Data collected from the medical charts included demographic characteristics, delivery outcomes, and health behaviors. Breastfeeding initiation and smoking during pregnancy were the primary variables of interest. A woman was considered to have initiated breastfeeding if the newborn chart indicated the baby was breastfed at least once during the delivery hospitalization. All women were asked one or more times during prenatal care (more than two thirds were asked at every visit) and at delivery admission whether or not they smoked. A woman was considered to be a pregnancy smoker if she self-reported, either at delivery or at any point during prenatal care, that she smoked. Women were also asked at delivery how much they smoked (number of cigarettes per day), and how long they had been a smoker (number of years), and this information was also recorded. Demographic and health characteristics recorded included maternal age, education level, marital status, race/ethnicity, participation in a government insurance program (proxy for family income), number of other children, and mental health history (considered positive if any self-report, either prenatally or at delivery, of any previous or current mental health problems, or 7 any prescriptions for medications typically used for mental health treatment were recorded). Delivery outcomes recorded included delivery type (vaginal or cesarean section), newborn nursery assignment (regular, special care, or neonatal intensive care), preterm birth (prior to 37 weeks gestation), and low birth weight (less than 5.5 pounds). Health behaviors recorded included infant feeding choice and smoking status as described above, pregnancy drug use (indication of illicit drug use, either via self-report during pregnancy or at delivery, or via universal urine drug screening conducted at the first prenatal visit and at delivery), pregnancy alcohol use (indicated by self-report during pregnancy or at delivery) and prenatal care utilization (adequate, intermediate, or inadequate, based on Kessner Index).36 Data Analysis Descriptive analyses were used to detail the characteristics of the sample, including breastfeeding initiation and pregnancy smoking rates. Power analysis revealed adequate power (β=.8) to detect small effect size differences between those who did and did not initiate breastfeeding on all variables of interest. Chi-square analyses identified demographic, delivery, and health behavior factors predictive of breastfeeding status. Relative risk was also computed. Logistic regression analysis was used to look at the unique predictive ability of each significant factor in predicting breastfeeding status, and to determine which factors were most strongly associated with breastfeeding initiation. Results of the logistic regression analysis led to the computation of relative risk of not initiating breastfeeding when considering multiple factors together. Finally, follow up chi-square analyses were conducted to examine the associations between amount of and length of time smoking and breastfeeding initiation. Results 8 Description of Sample Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1. The vast majority of participating women (over 95%) were Caucasian, and more than two thirds had completed at least a high school education. Half were married, with two thirds of women either having no medical insurance or qualifying for a government insurance program. The vast majority of the newborns were full term and assigned to the regular nursery. Many of the women had pregnancy risk factors including one in ten with a history of mental health problems, one third with less than adequate prenatal care utilization, one in ten with illicit drug use during pregnancy, and more than two in five smoking during pregnancy. Finally, only half of the women initiated breastfeeding. Insert Table 1 About Here Factors Associated with Breast Feeding Initiation Bivariate Analyses As detailed in Table 2, several demographic and health factors, as well as health behaviors, were significantly associated with breastfeeding initiation. Women 20 years of age and older, those with more than a high school education, those who were married, and those with private medical insurance were significantly more likely to initiate breastfeeding than the remaining women. Additionally, those for whom this was their first child were significantly more likely to breastfeed than those who had other children. Further, women who had adequate prenatal care utilization and did not use illicit substances during pregnancy were significantly more likely than remaining women to breastfeed. Finally, women who did not smoke were nearly twice as likely to initiate breastfeeding as those who smoked. Maternal mental health history and infant health status were not significantly related to breastfeeding initiation. 9 Insert Table 2 About Here Multivariate Analyses Results of the logistic regression analysis, used to examine the unique predictive ability of each factor in determining breastfeeding status as well as to determine which factors were most strongly associated with breastfeeding initiation, are also presented in Table 2. After control for all other significant factors, maternal education, marital status, type of insurance and primiparity all remained significant predictors of breastfeeding initiation. In addition, even after control for all demographic and health factors, women who smoked and women who had used illicit substances were still significantly more likely to not initiate breastfeeding. In fact, after controlling for all other potential predictors examined, other than childbearing history (i.e. having had another child), smoking status was the single strongest predictor of failure to initiate breastfeeding. Based on the results of the logistic regression analysis, a composite variable was computed for each woman based on her status on the four most highly predictive and common characteristics associated with breastfeeding initiation. Results of this analysis revealed that compared with remaining women, those who smoked, had never been to college, had other children, and were unmarried (13.3% of the current sample), were more than three times as likely to fail to initiate breastfeeding (RR=3.36, Χ2(1)=106,7, p<.001). In fact, only 24% of these women made the decision to attempt to breastfeed. Given the strong association between smoking status and breastfeeding status, follow-up analyses were performed to examine aspects of smoking that may be important in the decision to formula feed rather than breastfeed. Specifically examined were amount of smoking and number of years as a smoker. Women who smoked at higher rates were significantly less likely to initiate 10 breastfeeding (Χ2(4)=192.1, p<.001) than those who smoked lesser amounts. Half of those (51%) who smoked less than half a pack per day initiated breastfeeding, while only one quarter (25%) of those who smoked a pack or more per day breastfed. Similarly, number of years a women smoked was also predictive of breastfeeding (Χ2(2)=104.7, p<.001). Those who had been smoking fewer than five years were more likely to breastfeed than those who had been smoking longer than five years (41% vs 34%). Discussion The rate of breastfeeding initiation was barely 50% in the study sample, consistent with what we know about breastfeeding rates in the region. In addition, the findings of the current study point to many demographic and health characteristics that predict failure to initiate breastfeeding. While several factors emerged, whether or not a new mother was a smoker was the single strongest risk factor for not breastfeeding, with those who smoked at the highest levels also the most likely to formula feed in this primarily rural sample from the South. The southeastern states have traditionally had elevated levels of a number of risky health behaviors and, in particular had the highest rates in the U.S. for smoking, obesity, and physical inactivity.37-39 These rates are even more excessive in the region within Appalachia where the women in our sample reside (southeastern Kentucky, southwestern Virginia, northeast Tennessee, and southern West Virginia). For smoking specifically, we know that more than 30% of adults in the region smoke, with rates of smoking during pregnancy exceeding 40% in some of our local counties.34,35 This and other negative health behaviors are likely related to the low socioeconomic status, low educational attainment, and lack of access to medical care also found in the region. What this study has revealed about low rates of breastfeeding initiation and factors 11 most predictive of this specific health behavior further emphasizes the health disparities in this region of Appalachia. The results of the current study support, clarify, and expand on findings from previously published reports examining predictors of breastfeeding. As has been found in most other studies,16-21 maternal age and educational level were strongly associated with breastfeeding initiation in the current sample. In addition, our findings provide support for other studies that have identified links between breastfeeding initiation and factors such as marital status, socioeconomic status, and drug use.2,18-21 Our failure to find an association between breastfeeding initiation and both maternal mental health and infant physical health status may mean the current study is in line with other studies that have also not found such links.2,27 It could also be that these factors were not measured precisely enough in the current study for an existing association to emerge. Infant health status was classified simply by whether the infant went to a specialized nursery after delivery, and did not take into account how sick he/she might have been or how long he/she may have stayed. Similarly, maternal mental health status was rather crudely measured and relied primarily upon self-report and. Thus, we cannot definitively conclude that these factors are not predictive of breastfeeding initiation. A very powerful finding from the current study is the association between smoking and failure to initiate breastfeeding. Many other investigations have identified this link as well,16,17,19,29-31 although only a few have found the effect to be as large as that revealed in the current sample.29,30 Some have suggested that the link between smoking status and breastfeeding initiation may be spurious and merely reflects social status or level of education.17,21 However, our sample consisted of primarily low SES women and, even after controlling for other variables, the relationship between smoking status and breastfeeding initiation persisted. In addition, the 12 dose response finding that women who smoked the most were the least likely to initiate breastfeeding is consistent with one other study that examined amount of smoking,17 and may provide further evidence of a biologic effect. It could also be that smokers are choosing to formula feed based on the belief that their breast milk would be harmful to their babies. Contraindications and concerns about harming their infants by breastfeeding while smoking have been documented in women choosing to formula feed.33 Indeed, qualitative studies have noted that one of the primary reasons smokers fail to initiate breastfeeding, or discontinue it early, is because they believe that formula would be better for their baby than breast milk “contaminated” by smoking.40 This is not surprising due to the aggressive public health campaigns against smoking and the increasing awareness that unborn babies and children can be harmed by their mother’s smoking. Indeed, not a single smoking new mother in one qualitative study reported knowing or having heard from a health care provider that the benefits of breastfeeding might outweigh the harms of smoking while breastfeeding,40 consistent with the findings of a recent quantitative study.41 Certainly, all pregnant women and new mothers should be encouraged to stop smoking, both for their own health and the health of their infants. When a woman smokes, nicotine, or one of its metabolites cotinine, transfers to her blood, with the amount directly proportional to the number of cigarettes smoked. Circulating cotinine is also transferred to a woman’s breast milk.42 Consequently, the composition of smoking mothers’ breast milk differs from non-smokers’ milk in the amount of important lipids and fatty acids.43 Additionally, although most breast milk contains approximately 5-6 ng/mL of nicotine (from the diet), this level is significantly increased for smokers,32 and is directly related to the number of cigarettes smoked, putting infants of heavy smokers at highest risk.44 High levels of nicotine 13 in breast milk can lead to decreased pulse, respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation after the infant is fed.32 This effect is not seen in infants breastfed by non-smokers, and could be evidence of addiction to nicotine in the infants after a “withdrawal period” between feedings.32 Urinary cotinine levels of infants being breastfed by mothers who smoke are also higher, providing further evidence of the presence of nicotine in the infant’s system.45 Evidence is mounting that even in the absence of smoking cessation, breastfeeding is still the best choice and may even provide protection against the baby’s exposure to smoke.46 The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that breastfeeding should be encouraged, regardless of smoking status,47 and guidelines related to smoking reduction and timing of smoking and breastfeeding are available to reduce the impact of smoking exposure.32 Unfortunately, additional provider education regarding current recommendations is needed, as a recent state-wide survey of pediatricians in Pennsylvania revealed that fewer than half felt breastfeeding was safe for smoking mothers.48 Many experts agree that formula feeding is thought to only compound the negative health consequences of smoking as the infant is denied the benefits of breast milk and is exposed to environmental smoke.49,50 While additional research is needed, preliminary evidence suggests that compared with formula fed infants of smokers, breastfed babies of smokers do not experience growth restriction as a result of breast milk exposure to nicotine.51,52 Another study found that for children who were exposed to smoking in utero, breastfeeding appeared to ameliorate the effects on cognitive development, as breastfed babies of smokers had better school performance at age nine than did those who were formula fed by smokers.46 Finally, even though cotinine can be detected in the serum, saliva, and urine of infants breastfed by smokers, the levels are substantially lower than those observed in fetal blood, amniotic 14 fluid, and placental tissue of pregnant smokers.53 Thus, based on available evidence, breastfeeding while smoking does not appear to confer significant negative effects on the infant, especially compared with the likely substantial nicotine exposure that occurred prenatally, but does provide the infant with the substantial health and developmental advantages that breastfeeding offers. While the contributions of the current investigation to what we know about breastfeeding initiation are important, this study is not without limitations. Data were collected through chart review, and thus were limited to information routinely charted at the two hospitals. In the case of many of our variables of interest, which relied on self-report, social desirability responding bias may have played a role. In addition, questions about demographic factors and health behaviors were likely asked and potentially charted in different ways by different hospital staff, adding additional error and variation in responses. Finally, although the current sample is relatively representative of the rural Appalachian region from which it was drawn, it is very possible that the associations identified here may not be present in a demographically different sample. More research is needed to understand the reasons pregnant smokers are choosing to formula feed. Further research is also needed to examine the associations identified in the current study in other populations, and to determine which might be specific to a rural Appalachian sample. However, the current findings indicate that a number of demographic, medical, and health behavior factors place women at increased risk for failure to initiate breastfeeding, and this knowledge can further efforts to target these women for intervention. Finally, clinical efforts should be made to encourage a combination of smoking cessation and breastfeeding while emphasizing that breastfeeding is not contraindicated even if the mother continues to smoke. 15 References 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Breastfeeding Report Card – United States, 2009. At: http://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/pdf/2009BreastfeedingReportCard.pdf. Accessed 1/5/10. 2. Kogan MD, Singh GK, Dee DL, et al. Multivariate analysis of state variation in breastfeeding rates in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2008 98:1872-1880. 3. Mezzacappa ES, Guethlein W, Vaz N, et al. A preliminary study of breast-feeding and maternal symptomatology. Ann Behav Med. 2000;22:71-79. 4. Newcomb PA, Storer BE, Longnecker MP, et al. Lactation and reduced risk of premenopausal breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:81-87. 5. Yang CO, Weiss NS, Band PR, et al. History of lactation and breast cancer risk. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;138:1050-1056. 6. Altemus M. Neuropeptides in anxiety disorders: Effects of lactation. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1995;771:697-707. 7. Chantry CJ, Howard CR, Auinger P. Full breastfeeding duration and associated decrease in respiratory tract infection in U.S. children. Pediatrics. 2006;117:425-432. 8. Sacker A, Quigley MA, Kelly YJ. Breastfeeding and developmental delay: Findings from the millennium cohort study. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e682-e689. 9. Lawlor DA, Najman JM, Batty GD, et al. Early life predictors of childhood intelligence: Findings from the Mater-University study of pregnancy and its complications. Pediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2006;20:148-162. 10. Dee DL, Li R, Lee LC, et al. Associations between breastfeeding practices and young children’s language and motor skill development. Pediatrics. 2007;119(suppl):S92-S98. 11. Howie PW, Forsyth JS, Ogston SA, et al. Protective effect of breastfeeding against infection. Br Med J. 1990;300:11-16. 16 12. Forsyth JS. The relationship between breast-feeding and infant health and development. Proc Nutr Soc. 1995;54:407-418. 13. Gartner LM, Morton J, Lawrence RA, et al. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2005;115:496-506. 14. No Authors. Breastfeeding: Maternal and infant aspects. ACOG Educational Bulletin 258. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2000. 15. Protecting, promoting, and supporting breastfeeding: The special role of maternity services. A joint WHO/UNICEF Statement. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1989. 16. McInnes RJ, Love JG, Stone DH. Independent predictors of breastfeeding intention in a disadvantaged population of pregnant women. BMC Public Health. 2001;1:10. 17. Leung GM, Ho LM, Lam TH. Maternal, paternal and environmental tobacco smoking and breast feeding. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2002;16:236-245. 18. Yang Q, Wen SW, Dubois L, et al. Determinants of breast-feeding and weaning in Alberta, Canada. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2004;26:975-981. 19. Noble L, Hand I, Haynes D, et al. Factors influencing initiation of breast-feeding among urban women. Am J Perinatol. 2003;20:477-483. 20. Park YK, Meier ER, Song WO. Characteristics of teenage mothers and predictors of breastfeeding initiation in the Michigan WIC program in 1995. J Hum Lact. 2003;19:50-56. 21. Scott JA, Binns CW. Factors associated with the initiation and duration of breastfeeding: a review of the literature. Breastfeed Rev. 1999;7:5-16. 22. Sable MR, Patton CB. Prenatal lactation advice and intention to breastfeed: Selected maternal characteristics. J Hum Lact. 1998;14:35-40. 17 23. Hurley KM, Black MM, Papas MA, et al. Variation in breastfeeding behaviours, perceptions, and experiences by race/ethnicity among a low-income statewide sample of Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, infants, and Children (WIC) participants in the United States. Matern Child Nutr. 2008;4:95-105. 24. Petrova A, Hegyi T, Mehta R. Maternal race/ethnicity and one-month exclusive breastfeeding in association with the in-hospital feeding modality. Breastfeed Med. 2007;2:9298. 25. Peterson CE, DaVanzo J. Why are teenagers in the United States less likely to breast-feed than older women? Demography. 1992;29:431-450. 26. Ford K, Labbok M. Who is breastfeeding? Implications of associated social and biomedical variables for research on the consequences of method of infant feeding. Am J Clin Nutr. 1990;52:451-456. 27. Clements MS, Mitchell EA, Wright SP, et al. Influences on breastfeeding in southeast England. Acta Pediatr. 1997;86:51-56. 28. Amir LH, Donath S. Does maternal smoking have a negative physiological effect on breastfeeding? The epidemiological evidence. Birth. 2002;29:112-123. 29. Leston GW, Rosenberg KD, Wu L. Association between smoking during pregnancy and breastfeeding at about 2 weeks of age. J Hum Lact. 2002;18:368-372. 30. Yang Q, Wen SW, Dubour L, Chen Y, Walker Mc, Krewski D. Determinants of breastfeeding and weaning in Alberta, Canada. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2004;26:975-981. 31. Edwards N, Sims-Jones N, Breithaupt K. Smoking in pregnancy and postpartum: Relationship to mothers’ choices concerning infant nutrition. Can J Nurs Res. 1998;30:83-98. 18 32. Stepans MBF, Wilkerson N. Physiologic effects of maternal smoking on breast-feeding infants. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 1993;5:105-113. 33. England L, Brenner R, Bhasker B, et al. Breastfeeding practices in a cohort of inner-city women: the role of contraindications. BMC Public Health. 2003;3:28-36. 34. Bailey BA, Wright HN. Assessment of pregnancy cigarette smoking and factors that predict denial. Am J Health Behav. 2010;34:166-176. 35. Bailey BA, Jones Cole LK. Rurality and birth outcomes: Findings from Southern Appalachia and the potential role of pregnancy smoking. J Rural Health. 2009;25:141-149. 36. Kessner DM, Singer J, Kalk CE, Schlesinger ER. Infant Death: An Analysis by Maternal Risk and Health Care. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine and National Academy of Scientists; 1973. 37. No Authors. State specific prevalence of obesity among adults. MMWR Wkly. 2006;55:985988. 38. No Authors. State specific prevalence of cigarette smoking among adults and quitting among persons 18 to 35 years. MMWR Wkly. 2007;56:993-996. 39.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. U.S. Physical Activity Statistics. At http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/PASurveillance/StateSumV.asp. Accessed 8/24/09. 40. Goldade K, Nichter M, Nichter M, Adrian S, Tesler L, Muramoto M. Breastfeeding and smoking among low-income women: Results of a longitudinal qualitative study. Birth. 2008;35:230-240. 41. Bogen DL, Davies ED, barnhart WC, Lucerno CA, Moss DR. What do mothers think about concurrent breastfeeding and smoking? Ambul Pediatr. 2008;8:200-204. 19 42. Steldinger R, Luck W, Nau H. Half lives of nicotine in milk and smoking mothers: Implications for nursing. J Perinatol Med. 1988;16:261-262. 43. Agostoni C, Marangoni F, Grandi F, et al. Earlier smoking habits are associated with higher serum lipids and lower milk fat and polyunsaturated fatty acid content in the first 6 months of lactation. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57:1466-1472. 44. Woodward A, Grgurinovich N, Ryan P. Breast feeding and smoking hygiene: Major influences on cotinine in urine of smokers’ infants. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1986;40: 309–315. 45. Becker AB, Manfreda J, Ferguson AC, et al. Breast-feeding and environmental tobacco smoke exposure. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:689-691. 46. Batstra L, Neeleman J, Hadders-Algra M. Can breast feeding modify the adverse effects of smoking during pregnancy on the child’s cognitive development? J Epidemiol Community Health 2003;57:403-404. 47. AAP-American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Drugs. Transfer of drugs and other chemicals into human milk. Pediatrics. 2001;108:776-89. 48. Lucerno CA, Moss DR, Davies ED, Colborn K, Barnhart WC, Bogen DL. An examination of attitudes, knowledge, and clinical practices among Pennsylvania Pediatricians Regarding Breastfeeding and Smoking. Breastfeed Med. 2009;4:83-89. 49. Dorea JG. Maternal smoking and infant feeding: Breastfeeding is better and safer. Matern Child Health Journal. 2007;11:287-291. 50. Minchin MK. Smoking and breastfeeding: An overview. J Hum Lact. 1991;7:183-188. 20 51. Boshulzen HC, Verkerk PH, Reerink JD, Herngreen WP, Zaadstra BM, Verloove-Vanhorick SP. Maternal smoking during lactation: Relation to growth during the first year of life in a Dutch birth cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147:117-126. 52. Little RE, Lambert MD, Worthington-Roberts B, Ervin CH. Maternal smoking during lactation: Relation to infant size at one year of age. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;140:544-554. 53. Luck W, Nau H. Nicotine and cotinine concentration in serum and milk of nursing mothers. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1984;118:9-15.