A framework for the role of narratives in educational use of computer

advertisement

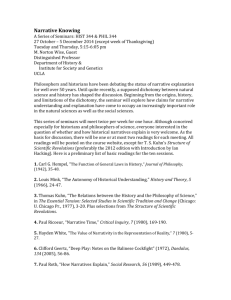

Version 0.5 17. June 2003 A framework for the role of narratives in educational use of computer games PhD student, Simon Egenfeldt-Nielsen Dept. of Digital Aesthetics & Communication IT-University of Copenhagen Glentevej 67, DK-2400 NV Copenhagen sen@it-c.dk This article explores how to progress beyond the traditional use of narratives in computer games with focus on the educational implications. The article starts with a general discussion of narratives in digital media, specifically computer games to establish the current understanding of narrative. Afterwards I move on to discuss narrative from a psychological point of view, where narrative is seen in relation to our everyday actions. The last step is to discuss the theoretical framework in an educational context, and examine the consequences. Initially narratives are not conceived as the exclusive property of computer games, neither of learning, but as one element in a complex process of interaction between subject and object, in a given context. Furthermore I will not treat learning in computer games from a narrow perspective, where learning is perceived as occurring only in games specifically constructed for educational purposes. Rather I see all computer games as possessing a potential for educational use, with some computer games more explicitly catering for this dimension. Learning should not only be seen as an intrinsic quality of computer games but also as constituted in a social context, where certain computer games have different potential for supporting a learning experience. For example SimCity has often been accentuated as a significant example of the possibilities for learning through computer games, specifically about urban space and city planning through experimentation with building and running a virtual city (Adams, 1998; Betz, 1996; Miklaucic, 2001; Prensky, 2001; Squire, 2002; McFarlane, Sparrowhawk & Heald, 2002). In the case of SimCity the intrinsic potential of games is used, the game design lends itself to educational purposes, and a there exist a potential for establishing an environment of social interaction around the game. It has almost become a mantra for people talking about computer games and their learning potential to bring forward SimCity, a second after Simcity has been mentioned, other familiar titles will emerge like Civilization and Railroad Tycoon. However it seems that SimCity is the game when it comes to having a metaphor for learning through computer games. Therefore it is also interesting that SimCity is quite an unusual computer game. First of all nobody expected SimCity to become a success – some even question if it qualifies as a computer game. Mainly the objections are connected with the lack of explicit goals in the game: how and when did you win. Will Wright, the designer of SimCity, has since become well known for his design style that he characterises with: 1/17 Version 0.5 17. June 2003 "Instead, we give them [the player] a rich environment with goals embedded in it [...] I’m interested in rewarding imagination: letting them leverage creativity to build an interesting external artifact of their imagination." (Brown, 2002)1. It is not the lack of goals that are central but rather the possibility to create a more open game universe: The goals are set by the player but are still a part of the game context. Especially the last part is quite interesting from a learning perspective, where Wright specifically label a large part of the game process, as the building of an external artifact of their imagination. From his perspective it seems that computer games are not well defined and finite for the player but instead a mental construction set. The player can interact and construct a game session, where his own prior knowledge and the game artefacts are combined. By this I do not mean to state that SimCity should be our preferred game form for educational use, however the success of SimCity point to the factors in games that educators and researchers find are interesting properties for educational purposes. These ideas seem to be that games for educational use should be open-ended, creative and toy-like, however this also implies that a lot of game titles would not be suited for educators’ purposes. These properties seem to limit the scope of games for education and favour the simulation genre, which have been the most discussed and researched genre since games entered education in the 1960’s (Dempsey et.al, 1993). The simulation genre lends itself well to the underlying learning paradigm in the game research community, namely experiential learning. We should however be careful not to perceive the ideas of experiential learning to literal, and we should not make experiential learning the only theory. On this background you can speculate that the Simcity is a natural extension of earlier work and research in game research, however we should not confuse the metaphor with the content. Simcity is an excellent metaphor and champion for educational use of computer games, however there are certainly our game genres, which are worth while to pursue – they may not be so obvious but still have the necessary content and form. In the following I will sketch the current discussion of, what a game is, and prepare the ground for a look at narratives in computer games. Although a computer game on the surface may seem quite simple and straightforward, built on simple rules, this is a faulty position based on inadequate external observations of the play situation 2. The focus on simple rules will formally describe a game, however the importance of rules in games is far from enough to give the full picture A game is more than meets the eye, you might say. It is worth remembering one of the first formal analyses of a computer game by Patricia Greenfield back in 1984, where she looks closer at Pac-Man. Much to her surprise the computer game is far from simple but requires the player to analyse the ghost’s behaviour, set-up strategies for different levels, and acquire the necessary navigation skill. The game is open to construction, interaction, and change over time, as the player's abilities improve. In an interview with Pearce (2002) at Game-studies.org Will Wright’s design style is even more fleshed out. 2 I am referring to several discussions here for example on emergence in computer games (Wright, 2003; Johnson, 2001) and the social interaction around computer games (Jessen, 1999). 1 2/17 Version 0.5 17. June 2003 When Henry Jenkins (2002) in his paper Game Design as Narrative Architecture, points to the obvious problems of applying film theory to computer games, the flexibility of the game universe is one of the key points. He states that he wants to formulate a position “examining games less as stories than as spaces ripe with narrative possibility” (Jenkins, 2002:2). A game supports different interpretations and routes through the game. He is trying to follow in the footsteps of legendary game designers like Will Wright and Sid Meier. The game is not characterized by linearity, like other media, but he stresses that this doesn’t mean, that the narrative potential is all lost. He advocates for diversity in the genres, the aesthetics and the use of narrative in games. Although I sympathies with his ambition I do not agree with his analysis of the current game industry, as one trying new concepts like the examples he brings forward: The Sims and Black & White. The Sims is a mainstream game borrowing heavily from old games like Mud1 and Little Computer People. And although Black & White have a clearer angle on the option for being a good or bad god, the basic principle is close to the old Bullfrog title Populous and similar godgames. However the point is still valid; narratives should have different roles, and be allowed to have different strengths and roles to play in computer games. Indeed this is the case, when we look at the use of narrative in different game genres (EgenfeldtNielsen, 2003a). A look at different definitions of narratives The discussion of the role of narrativity in games is often closely linked to the discussion of the nature of computer games. On one side narratologist is struggling to fit computer games into an existing paradigm, where the story is the significant part. Until now they have not been faring very well, and have been heavily criticized, with Espen Aarseth (1997) as one of the most well known critics. The so-called ludologists see computer games as an extension of games and play (Frasca, 1999; Eskelinen, 2001). I will not go in depth with what ludology have to offer in this paper but concentrate on the narrative part. Before venturing into a discussion of the potential of narrative in computer games for learning, it will be worthwhile to take a closer look at, what is meant with the term narrative. The definitions are many, and I will not go into all the definitions but concentrate on three different views on narrative. I have chosen Marie-Laure Ryan’s, and Janet Murray’s as a starting point as their work on narratives in digital media have influenced the field considerable over the last years. Furthermore they supplement each other, and illustrate some of the main problems in using narratives in computer games. This discussion will show the problems of current digital narrative theory, and leads the way for a new perspective on narrative by Jerome Bruner, which is informed by a psychological tradition. This tradition is closer to the goal of this paper, namely to address the role of narrative in educational application of computer games from a learning perspective. Murray (1997:180) stress that “we cannot bring to a transformative, shape-shifting medium the same expectations of static shapeliness and finality that belong to linear media.” Murray is not talking specifically about computer games but it seems that her 3/17 Version 0.5 17. June 2003 account of the consequences for using narratives in digital environments, is especially true for computer games, these in some ways being the very front-runner of transformative and shape-shifting media. Her account offers us three different perspectives on what aesthetics and pleasures the new medium offers us: Immersion, agency and transformation, which she believes will have to be staged through a new narrative style called procedural authorship. The procedural authorship is characterised by an ability to draw the user into the digital experience, and provide a frame for the experience, building blocks, more than a fixed linear pattern. In this way Janet Murray’s description of the digital universe lies close to Will Wright’s design philosophy and Henry Jenkins’s ideas. However her insistence on keeping the narrative in the foreground clouds the picture. Towards the end Murray (1997:275) points specifically to computer games, as a place, where we see this future almost in place. She is not only referring to classic narrative game examples like Myst and Kings Quest but also points to a game like Mario Brother’s. By pointing to a platform game like Mario Brother’s she is entering into dangerous territory. It seems obvious that the adventure genre, and it’s sub genre roleplaying games (RPG), draws on narratives elements. These two genres do obviously have immersion, agency and transformation as important parts, where magical spells of change, immersion into the fantasy world, and the power to make things right through righteous agency, are important ingredients. However these characteristics are not so clear when we turn to other computer game genres like action, strategy, and simulation 3. But, lets start with the game Murray uses as an example it belongs within the action genre. The game Mario Brothers is about controlling a plumber, jumping between platforms, avoiding obstacles while getting different objects for extra points. Starting with agency, it is clear, that there is a high degree of player control, but it is not as such a very immerse experience into the digital environment, as a plumber. There are some transformative aspects like jumping on obstacles so they go flat but they are not that noticeable in the game. It seems that when the player is focused on the game, it is the navigation and movement that are fascinating: Running, jumping and stopping at the exact right time, to avoid holes or monsters. Living up to the games rules, not because they are interesting from a narrative point of view, but because the rules are challenging and intrigue your explorative desire. When you observe children playing computer games their fascination and experience is seldom described by drawing on narrative theory (Jessen, 1999). In the old days, where piracy also where common, many players didn’t have a clue that Mario was a plumber. The narrative in the game was lacked the usual support of the cover, manual, and often hackers also removed the intro to the game. The players just saw an avatar, which should avoid obstacles and gain points by gathering objects. In this perspective the agency, immersion and transformation becomes to weak for describing the experience. Although they have bearing on the game experience, they do not grasp the fundamental dynamics and structures. The procedural authorship offers us some indications of, what goes on in the game but somewhat out of focus, as it still holds on to a narrative scripting of an event, that isn’t really conceived as narrative by the player. We have to turn to ludology for an explanation of games’ basic aesthetics and 3 For an explanation of my definition turn to Egenfeldt & Smith (2000). 4/17 Version 0.5 17. June 2003 pleasures. It is not by chance that we call it computer games, as computer games have a lot in common with games as such. Jesper Juul (2003) has described some of these mechanisms focusing on properties like for example; a game have rules, goals, and emergent patterns. However in this paper I will stay with narratives for a little longer, still pursuing the scope of narrative in games. Murray’s definition of a narrative is a framework, which only gets us so far. The metaphor is not very precise; instead we should find a metaphor, which more clearly demonstrates the process of games as affordances for the player’s experience. In The Design of Everyday Things (1988) Donald A. Norman defines affordances, as the actual properties of an object, a user perceive, and determines what the object can be used for. In respect to the objects we encounter. “Affordances provide strong clues to the operation of things” (Norman, 1988:9). In this perspective Henry Jenkins (2002) and Jonas H. Smith’s (2002) architecture metaphor is more fitting. Buildings and surroundings support different ways of perceiving an environment and your scope of action. I would argue that it is more constructive to see game elements from an affordances perspective, where the player can choose between different operations. This way the actions in the game is not necessarily contained in a narrative perspective but the narrative is still maintained as an opportunity. This is also what Murray is looking for with her concept of procedural authorship but she keeps it within a narrative framework. Still I believe narrative have a place in a computer game theory, and that we can come a bit closer to the difference between narrative in computer games and other digital media, through Marie-Laure Ryan’s transmedial definition of narrative. Ryan’s definition is more basic, than Murray’s thoughts. In her paper Narrative: A Transmedial Definition Marie-Laure Ryan (2004) identifies three properties of a narrative script, which are necessary for a narrative script to function: 1. A narrative has a world with characters and objects (Immersion) 2. The world must change either as a consequences of user actions or events (Agency). 3. It must be possible for the user to ‘speculate’ around the events hereby creating a plot (Transformation). In this perspective the basic building blocks of Ryan and Murray are close to each other with Murray’s concept in brackets behind each point above. The obvious difference is in point one, where Ryan identifies characters and objects. Murray on the other hand focus on immersion, where a world with characters and objects is a necessary prerequisite. In this sense Murray is more focused on describing the narrative experience where Ryan focuses on the narrative structure. Both perspectives are relevant but Ryan’s definition has the advantage of making it possible to distinguish between levels of narrativity in games, which is quite useful, if we want to discuss narratives across computer game genres, and the place of narratives in learning. The levels of narrativity can be thought of as a continuum reaching from “possessing narrativity” to “being a narrative”. Marie-Laure Ryan (2004) advocate this distinction and sees being a narrative as attributable to the text (game), however in order to posses narrativity the text must be able to evoke the 5/17 Version 0.5 17. June 2003 narrative script in the user through immersion, agency, and transformation. So even though a game is a narrative it doesn’t necessarily posses narrativity in the sense that the player is able to construct a meaningful narrative out of the game universe and its affordances. For example the game Mario Brother’s has a world with characters, object, and these changes as a consequence of a player’s actions, or by a random pattern, however the game do not necessarily posses narrative qualities from the players view. It is possible to speculate around the events of the plumber, killing monsters, getting closer to freeing the princess in the end, but the players only engage in this behaviour to a limited degree, and it is not the primary dynamic of the game. The distinction between being a narrative, and possessing narrativity, is especially important in relation to computer games for two reasons. We can observe that games are often set in a game universe with some resemblances to the real world, and the player’s actions are fundamental for the game experience. Excluding very abstract computer games like Tetris, and Pong, games often do have objects, obstacles, and characters, which are interconnected, and change during the game as a consequences of the player’s action. It is possible to speculate around the game events but in a lot of games, it doesn’t really make sense. The meaning attributable to the narrative is so insignificant that it doesn’t qualify as a narrative, in the player’s interaction with the game. This is primarily because the player’s actions are not meaningful in relation to the game’s narrative. It does not make sense to connect, the plumber on a rescue mission for his loved one, with head butting little boxes to gain points. Even though the narrative potentially is there, and the objects, characters and events are interrelated, it is not deep and relevant enough to engage the player meaningfully. An example from the related world of board games might prove useful to demonstrate, the fuzzy border between possessing narrative and being narrative. It has become popular to make classic games with a brand attached to it like for example the board game Risk has lately been published in a Lord of The Rings version. The first version of Risk was quite abstract, and the only background story, was something like conquering the world. You had a world map, some plastic pieces, rules, and cards with cannons, soldiers, and cavalry. Through these few clues the scene was set: A war for world domination sometime in the Century4. Picture 1: The game board for Risk with plastic pieces and cards. beginning of 19. In the Lord of the Rings game, the setting is a little different but the rules are basically the same. The question is if the setting in the Lord of The Rings version has an 4 Later a version was released with more detailed pieces, and a more colourful map, which could be seen as a first step towards ‘other’ versions of Risk. 6/17 Version 0.5 17. June 2003 impact on the game experience. The two games have the same amount of narrative scripting (Ryan’s three basic elements), however the Lord of The Rings world are initially much stronger supported with the alleged target group of Tolkien’s fans and we would expect the experience to posses some degree of narrativity. So, despite the fact that narrativity remains weak in the Lord of The Rings version of the game, it still seems to have a bearing in the Risk game, where it is actually possible to connect the game actions with the overall narrative. The narrative elements have an impact but it is outside part of the game experience. The border remains fuzzy, and do both depend on the narrative scripting and the player’s capacity for understanding these narrative elements. The relation between narrative, language and mental images Marie-Laure Ryan (2004) states that she finds that language is one of the best carriers of narrative but that narrative is not a linguistic phenomenon but rather a cognitive phenomenon, where we construct a mental image of the experience we participate in. Taking this further, the mental image comes before the narrative. We construct a mental image of the activity we are engaged in and only when we reflect over it, under special circumstances, do we turn it into a narrative. In this way narratives become a way to understand and handle the world by making it meaningful. If we turn to the psychologist Jerome Bruner (1990: 67-99) the importance of seeing narrative as something very fundamental becomes clear. According to Bruner, language is learned through praxis, which he calls an everyday drama: narratives without a narrator. Bruner sees the first drive for acquisition of language as a way to control these everyday narratives, and frame them according to ones own goals and pleasures. Therefore it is not strange that to understand and communicate narratives the natural medium is language, which originally is a way to master our everyday life, and frame it to our benefit, by using narratives. However it is also very clear that the experience of a narrative is not related to language per se. It doesn’t really make sense to call our everyday experiences for a narrative, even though they resemble them. Our everyday experience is life but when we talk about them and change them through language manipulation, they become narratives. To make events manageable we narrate them, and put perspective on. Therefore the experience through agency of a computer game player is not to be seen as a narrative but rather the other way around. The player venturing into a game, experiencing things, and dealing with these, is participating in virtual life. Like life itself it can with different degrees of relevance and success be transformed into a narrative. But, just like life, the game is not a narrative as such although it as life may have narrative potential (Remember Ryan’s distinction between being a narrative and possessing narrative). Drawing on Bruner (1990) the narrating process is often activated when it violates canonical narratives. Although life in action is not a narrative we still constantly live and navigate in and through narratives. Everyday life is framed within a social praxis that consists of canonical narratives, but these are not explicit in our everyday life, rather background noise. When the background noise comes to much out of tune with our life (narratives are violated), we search for ways to make these deviances meaningful. The language becomes a tool for the narrative process. 7/17 Version 0.5 17. June 2003 With this theoretical framework it is important to hold on to a genre definition, where we can pinpoint games that heavily draw on language for supporting the game experience and thereby lend itself more easily to narratives, games like Baldurs Gate II and Gabriel Knight III.5. In games like Deus Ex and Metal Gear Solid we see extensive use of language to construct the story in the game, thereby supporting the story by making the user reflects on it constantly through the dialogue. In games like Age of Empires II and Civilization III the setting is supported through a written introduction. The narrative is not really a part of the game but still sets the scene. Just like in real life where we accommodate to a specific social praxis, where the norms, rules and expectations are set through narratives (Bruner, 1990) when going to a fine restaurant or a soccer match. In game genres like action, strategy and simulation we do not need language to ‘sort out’ the narrative. Life is played out through the game, with physical actions within the game. We are not just dealing with narratives but engaging in virtual life – where we can try different paths, with limited consequences. We do not reflect it; we do it. This is perhaps also why some people acclaim games with the power to make real changes through their simulation power (Schank, 2000). Allegedly it should be important whether a game is linear or non-linear. Some considers this one of the true blessings of computer games, and what sets them aside from other media - they are interactive and non-linear (i.e. Crawford, 1982). This implies that games should be more like life, and more non-linear than other media forms. Often a comparison is made between classic linear narrative media and new non-linear narrative media (among others computer games). This distinction is not very adequate as it is a matter of perspective. A typical game is not more or less linear than a traditional book or movie. What is apparently meant by non-linearity is that the player can choose different endings, and ways through the game but emphasising specific parts. But this is not necessarily different from a book or movie. Here the viewer can also choose to pay more attention to a specific scene, concentrate on a specific chapter or sympathize with a specific character. The difference is in the enactment of the narrative. In the book or movie, it is a mental image constructed, modulated by language, visuals and perhaps even discussed and formed with other people through discussion. In a computer game the experience is formed as a physical process through your senses, where you choose to focus on specific elements in the game universe. You are forming mental images but more importantly enacting them. In this process you are not choosing between different narratives but being a human in a certain social setting – doing things. In other media the narratives are (merely) perceived and processed by the subject but in computer games the elements for the potential narrative are constructed. The player must choose between different options, and by doing this make different narrative possible 6. 5 This does not imply that audiovisual elements do not have an important role to play in constructing narrative but merely that they are not the primary vehicles. It is significantly harder to construct narratives merely through music or silent movies but not impossible. 6 Frasca (1999) argues along similar line of perspective underlining the difference between ludus and stories. 8/17 Version 0.5 17. June 2003 Murray is also thinking along these lines but doesn’t consider the difference between computer games and other media an unsolvable problem. She concludes: “Games are limited to very rigid plotlines because they do not have abstract representations of the story structure… That is, ‘level two’ of a fighting game always refers to the same configuration, not to a set of rules by which it can be constructed.” (1997:198, my italics). Therefore the narratives and plots in a game are not very varied. The point is that it is really hard to build, frame and manipulate a narrative, when you do not have language (abstract representations) as the primary communication form. You may argue that films are capable of this but it seems that even the most language limited film genres like Westerns do use language to frame and manipulate the narrative. The game universe is not build through language but through a wide range of means like genre awareness, kinetic activity, spatial, and audiovisual dynamics. Language plays a smaller role, and is usually not necessary to come to terms with, what is going on in the game, by creating a narrative. 7 At least not until someone ask you, and you thereby reflect on your practice. Or when you have to make sense of a specific conflict or problem in the game, these usually being objects, characters or events that deviate from traditional genre, narrative or medium scripts. The point I want to stress is that we should not be fooled into believing that games are necessarily better off by drawing more heavily on abstract representation (language). Games have other means and effects for achieving its goals. Games are closer to our everyday activities than to other media types, and we should not built on top of classic media theory. Instead you will have to move closer to theories of everyday life, to understand, what goes on in computer games. For some reason the discussions of the nature of games are often waged within a narrative or ludologic setting, when it is really closer to an everyday encounter. A notable exception is Goffman (1972). An everyday encounter is non-linear, interactive, physical, and audiovisual in the sense that we move between contexts and perform actions, which are not necessarily linked beyond being connected in time. The distinctions between contexts are often made through narratives but then we have different narratives for different situations, depending on the activities. Our involvement and activities in life are perhaps motivated and framed by narratives – stories about who we are (i.e. Giddens, 1991; Bruner, 1990) but they do not explain, why it is fun to bungee jump, drive fast, get a massage or other activities. However they do to a large degree explain why it is fun to watch a movie, read a book, socialize with people, or gossip. Characteristics of games in a learning context from a narrative perspective So in the majority of games (action, strategy and simulation genre), narratives are not the main attraction. In these games the dynamics comes from playing with life in a social 7 This also partly explains the text-MUDS continuing popularity, and game designers frustration, when building open online-worlds (Smith, 2002). 9/17 Version 0.5 17. June 2003 praxis with another frame than everyday life. Just like everyday life happens within an overall narrative (Bruner, 1990), so does games but without taking on immediate consequences to our everyday life. The narrative is framing the perception. From a learning perspective this is quite interesting, as this is actually close to the very definition of a learning environment. It is a place where we can experiment and gain important experiences and knowledge, without too much risk (Dewey, 1938). It has long been argued that games are well suited for offering the opportunity to practice and experience different areas without the consequences of real life (Boocock, 1968). The main question is how strong the relation between the digital learning environment and everyday life is. Adventure computer games are a popular way to create a digital learning environment through games although the evidence on the learning outcome and the correct teaching application is limited (Cavallari et al., 1992). In a study by Oluf Danielsen, Birgitte Ravn Olesen & Birgitte Holm Sørensen (2002) a school class plays an environmental adventure game, and experience different events, thereby forcing them to think about environmental issues. What is interesting in their research project is that the degree of success is measured through test questions on environment, and it supports the researchers in their conclusion that learning do occur. The environmental information are presented through language, and tested through language. However this does not mean that the children change their everyday practice, in this study the researchers found this to be unlikely8. With the exception of the few homes, where the children parallel with the computer game playing in school, engaged in environmental relevant behaviour. When the children at home engaged in environmental issues it became possible for the players to cross the border between the narratives constructed through language by playing the game, and their everyday activities. Adventure games are quite traditional and close to the written media in their learning process, using language as the primary requisite 9. Therefore it also makes sense to talk about a narrative to a certain degree although it is rather clumsy implemented in this particular environment game. However the adventure game rest heavily on traditional learning theory, where we acquire information and then learn about them. We read or hear information, and then learn them (Schank, 1999). In opposition to this learning theory I will point to experiential learning represented by John Dewey (1938) and David Kolb (1984), which stress then importance of ‘Learning by Doing’. In their perspective it is not enough to simply hear or read some information, we have to engage with them, and connect it with our existing knowledge and concept. Another example of a learning game, which lends itself more to experiential learning perspective is Bronkie the Bronchiasaurus presented by Debra A. Lieberman (2001), which is within the action genre, in the sub genre called platforms games. You control Bronkie, a little dragon that must fight the bad Tyrannosaurus Rex to assemble a wind machine to clean the air. During the game you must fight evil dinosaurs, and engage in proper asthma management to win the game. The story has minor significance except setting the scene, and is quickly forgotten, when you jump over enemies and avoid 8 This finding is supported by another Danish study by Estrid Sørensen (1997) on a health game to teach children on healthy food, where the problems of transfer is highlighted although the focus in not on the limits of language. 9 This is probably also the explanation for literature, film, and media studies higher interest in adventure games compared to other genres. 10/17 Version 0.5 17. June 2003 obstacles that will deteriorate your asthma, trying to make it to the next level. In the game a lot of necessary asthma management tools are embedded in the game universes and the activities you perform. The use of language is limited to a few multiplechoice questions between levels. The pre- and post-test are not done through language, but is rather observed directly in the children’s everyday life, where the game leads to significant improvement. These improvements were for example observed in communication about asthma with peers, clinical staff and parents. Bronkie the Bronchiasaurus. Packy & Marlon In another similar game called Packy & Marlon the same guidelines were used for helping children to improve their management of diabetes’s. Here, in addition to improved communication, a post-test showed a 77-percent drop in visits to urgent care and medical visits (Lieberman, 2001). In best case the information the game designer wishes to convey to the player is part of the game experience like in Bronkie the Bronchiasaurus and Packy & Marlon. Here primers for the information you wish to convey have been integrated as a natural part of the game activity and are necessary for succeeding in the game - the game actions are directly related to the behaviour you want to learn the player. The adventure games do have a potential for learning as have been argued by Amory et.al (1999) but I argue that the real potential for learning through games lies in other game genres like the action, strategy and simulation genres, where virtual life is to a higher degree practised. Here the social virtual praxis is constituted through narratives but as in real life the narrative is a distant, framing device. In everyday life it is possible to manipulate these narratives through language, framing a situation differently, or exploring other narratives by reading them. But the narrative part comes after the game experience, after we have done something. Before challenging our experience through narratives we have to experience ‘something’ – both in life and virtual life. We have to get the small blocks for toying with in the game before we engage in reflection, and narrative discourse. Computer games can very well be the carrier of this something, providing it can give the necessary physical sensations (audiovisual, tactile, kinetic, and motor skills) for a given situation to be constructed meaningfully by the player. The real challenge when using computer games for learning, is to stay focused on the areas, where computer games can give a better learning experience: Not because the player is ‘tricked’ into the learning processes through his favourite pastime but because the computer game can offer a safer, better, and fuller experience. With a safer, better, and 11/17 Version 0.5 17. June 2003 fuller experience I am referring to the game as environment, where you can explore, experience, and manipulate without the same risk as other environments, and get input that is otherwise more restricted. One example is the use of Simcity for illustrating the dynamics of urban planning (Adams, 1998), where you get a fuller experience in the teaching situation than if you read about urban planning or the teacher lectured about it. The use of Simcity in a course does not make the other contributions obsolete but rather add another dimension. The safe environment of games should be understood in relation to for example actually running a city, which could have dire consequences. The finding that games makes for a better experience is one of the most widespread if you look at earlier research on games and learning as retention over time increased, and the students are more motivated (Egenfeldt-Nielsen, 2003b). Although this research focuses on games in general the claim is also supported in the few studies currently conducted with computer games. In the genres, action, strategy, and simulation, the simulation potential of games is a much more interesting feature than language driven adventure games. The narrative experience is formulated and constructed by the player (under the right circumstances) for example about how he managed asthma in a game, or changed light bulb from a normal bulb to a low-energy bulb. Although this is beyond the scope of this paper it could be argued that a design strategy for games for facilitating learning could be to strengthen the game’s narrativity by leaving it to the player’s imagination to form a narrative interpretation, rather than explicitly telling a story through language. Perhaps this explains the attention that SimCity have drawn in educational circles. As I explained at the start of this paper Simcity is characterized by giving the player more options for setting own goals, and playing the game. It becomes possible for the player to play a game of own device, and to construct a narrative experience, which supports their game experience, and not the game designers. I believe I have argued that all learning cannot reasonably be reduced to a narrative. However the narrative does have significant importance as it gives the concrete elements in the learning experience meaning, affective strength and situate it in accordance with the player’s perception. The narrative is not the knowledge but supports acquisition of knowledge. It is like the string that pearls are put on, and the string never bends the same way. This is just to say that a game’s success as learning tool cannot only be measured as its ability to facilitate the player’s construction of narratives. Other factors will certainly come into play for example the precision of information depicted in the game, the degree of freedom to interact with the information, and the presentation of information. However I will not elaborate more on these topics here. In this perspective the closer a game simulate real life, the better. This is not necessarily the whole truth. In the future work will have to be done on identifying different learning set-ups in computer games. For example some games will benefit from a realistic representation, where other games are characterised by reducing the information complexity. The reduced complexity could be seen as a way of empowering the player, a virtual guided tour. Hereby facilitating a zone of proximal development in a Vygotskian sense (Vygotsky, 1978:86). When examining learning games from a simulation perspective (learning by doing) we would be wise to be cautious with games trying to communicate abstract information, 12/17 Version 0.5 17. June 2003 concepts and ideas, which are learned through language, and are primarily represented by language. By using language we run the risk of reducing the player’s creative options severely to the process of constructing a narrative. This is not sufficient; instead we should stress the importance of actually engaging in play, and do things in a safe environment. We should also be wary of our tendency to fit our conception of learning games within the current educational practices, which clearly supports learning through language. Furthermore we should be aware that the computer game genres today are quite rigid, and the expectations of the players make it limited what activities they will engage in. Computer games are conservative in their content, interface, narrative, use of time, space perception, and progression. 13/17 Version 0.5 17. June 2003 References Adams, Paul C. (1998). Teaching and Learning with SimCity 2000. Journal of Geography; Vol. 97, No. 2. 47-55. Aarseth, Espen (1997). Cybertext: Perspectives On Ergodic Literature. John Hopkins University Press Amory et. al (1999). The use of Computer Games as an Educational Tool: Identification of Appropriate Game Types and Game elements. British Journal of Educational Technology. 30(4). 311-322. Betz, Joseph A.. (1996). Computer Games: Increase Learning in an Interactive Multidisciplinary Environment. Journal of Educational Technology Systems. Vol. 24, No 2. 195-205. Boocock, Sarane (1968). From Luxury Item to Learning Tool: An overview of the Theoretical Literature of Games. In: Boocock, Sarane & Schild, E.O. (1968). Simulation Games in Learning. London: Sage Publications. Brown, Janelle. “Payoff = Points: A False Equation”. New York Times. Oct 24, 2002. Bruner, Jerome (1990). Acts of Meaning. Cambridge: Harvard University Cavallari, John, Hedberg, John & Harper, Barry (1992). Adventure games in education: A review. Australian Journal of Educational Technology. Col. 8, No. 2:172-184. Danielsen, Oluf, Birgitte Ravn Olesen & Birgitte Holm Sørensen. ”From Computer Based Educational Games to Actions in Everyday Life.” In: Danielsen, Oluf, Nielsen, Janni & Sørensen, Birgitte Holm (eds.) Learning and Narrativity in Digital Media. Aarhus: Samfundslitteratur, 2002. 67-81. Dempsey, J., Lucassen, B., Gilley, W. & Rasmussen, K.. (193). Since Malone's theory of intrinsically motivating instruction: what's the score in the gaming literature? Journal of Educational Technology Systems, Vol. 22 No.2, 173-83. Dewey, John (1938). Experience and education. Kappa Delta Pi. Egenfeldt-Nielsen, Simon (2003a). Exploration in games – a new starting point. Version 0.4, May 2003. Work in progress. Egenfeldt-Nielsen, Simon (2003b). Getting to the right question: A review of the literature on simulations, games and computer games for learning. Version 0.4, June, 2003. Work in Progress. Egenfeldt-Nielsen, Simon & Jonas Heide Smith (2000). Den Digitale leg – Om børn og computerspil [Digital Play – About children and computer games]. Copenhagen: Hans Reitzel Forlag. 14/17 Version 0.5 17. June 2003 Eskelinen, Markku (2001). ”The Gaming Situation.” Game studies, volume 1, issue 1 (2001). 23.10.2002 http://www.gamestudies.org/0101/eskelinen/ Frasca, Gonzalo (1999). Ludology meets Narratology: Similitude and differences between (video)games and narrative. Parnasso 3 (1999): 365-371. Giddens, Anthony (1991). Modernity and Self-Identity. Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Cambridge: Polity Press. Goffman, Erving (1972). Fun in games. I: Goffman, Erving (1972). Encounters. London: The Penguin Press. 15-31. Greenfield, Patricia (1984). Mind and Media: The Effects of Television, Video Games, and Computers. Harvard University Press. Jenkins, Henry (2002). "Game Design as Narrative Architecture. In: Harrington, Pat & Frup-Waldrop, Noah. ” First Person. Cambridge: MIT Press. http://web.mit.edu/21fms/www/faculty/henry3/games&narrative.html Jessen, Carsten (1999). Computer games and play culture - an outline of an interpretative framework. In: Christensen, Christa Lykke (red): Børn, unge og medier. Nordicom: Nordiske forskningsperspektiver. http://www.carsten-jessen.dk/compgames.html Juul, Jesper (2003). The Game, the Player, the World. A transmedial definition of games. Version 20, April 2003. Work in progress. Johnson, Steve (2001). Emergence: The connected lives of ants, brains, cities, and software. London: Allen Lane Penguin Press Kolb, David A. (1984). Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, N.J. McFarlane, Angela, Sparrowhawk, Anne & Heald, Ysanne (2002). Report on the educational use of games. Teachers Evaluating Educational Multimedia. Date of access: 1 May 2002: http://www.teem.org.uk/howtouse/resources/teem_gamesined_full.pdf Norman, Donald A. (1998). The design of Everyday Things. Cambridge: MIT Press. Pearce, Celia. Sims, Battle Bots, Cellular Automata God and Go. A Conversation with Will Wright by Celia Pearce. Game studies, Volume 2, issue 1 (2002). 23.10.2002 http://www.gamestudies.org/0102/pearce/ Prensky, Marc. Digital Game-based learning. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2001. Ryan, Marie-Laure (2004). “Narrative: A Transmedial Definition.” In: Ryan, Marie-Laure. (2004). Narrative Across Media. University of Nebraska Press. In press. Schank, Roger (1999). Learning by Doing. In: Schank, Roger (1999). Dynamic Memory Revisited. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Schank, Roger (2000). Colouring outside the lines. New York: Harper Collins. 15/17 Version 0.5 17. June 2003 Shawn Miklaucic (2001). Virtual Real(i)ty: SimCity and the Production of Urban Cyberspace, 2001, http://www.game-research.com/art_simcity.asp Smith, Jonas J. (2002). The Architectures of Trust: Supporting Cooperation in the Computer-Supported Community. Master's Thesis. Film- and Media studies Copenhagen University, 2002. Smith, Jonas J. (2002). Stories from the sandbox. Game-Research.com. http://www.game-research.com/art_stories_from_the_sandbox.asp Squire, Kurt (2002). Cultural Framing of Computer/Video. Game studies, Volume 1, issue 1 (2001) 23.10.2002 http://www.gamestudies.org/0102/squire/ Sørensen, Estrid (1997). Kan man lære noget af fiktion? [Can you learn anything from fiction?]. Master Thesis. Copenhagen University, Psychology. Vygotsky, (1978) Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Harvard. Wright, Will (2003). Dynamics for Designers. Talk at GDC march, 2003. 16/17 Version 0.5 17. June 2003 Relevant game titles Age of Empires II (Microsoft, 1999) Baldurs Gate II (Interplay, 2000) Black & White (Electronic Arts, 2001) Bronkie the Bronchiasaurus (Raya Systems 1994) Civilization (Microprose, 1991) Civilization III (Infogrames, 2001) Deus Ex (Eidos Interactive, 2000) Gabriel Knight: Sins of the Fathers (Sierra, 1993) Kings Quest (Sierra, 1984) Little Computer People (Activision, 1985) Lord of The Rings: Risk clone (Parker Brothers, 2002) Mario Brother’s (Nintendo, 1983) Metal Gear Solid(Konami, 1998) Mud1 (Bartle, 1978) Myst (Brøderbund, 1994) Packy & Marlon (Raya Systems 1997) Pac-Man (Bally/Midway. 1981) Populous (Electronic Arts, 1989) Railroad Tycoon (Microprose, 1990) Risk (Parker Brothers, 1959) SimCity (Maxis, 1987) The Sims (Electronic Arts, 2000) Biography PhD student IT-university of Copenhagen, master degree in psychology, founder of Game-research, reviewer Game studies, and student officer Digra. Have done research on educational games, online gaming, exploration in games, effects of computer games, and play theory. Authored two Danish books on computer games and education, written several articles in the field, and regularly give talks on the subject. 17/17