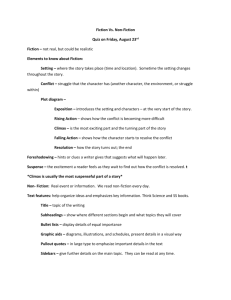

Science fiction`s use of Utopian and Dystopian visions of the future

advertisement

Science fiction’s use of Utopian and Dystopian visions of the future in relation to challenging boundaries of gender and / or sexuality: Ghost in the Shell and Tenkuu no Escaflowne. Science fiction has been used from the beginning to explore issues that have been dubbed controversial and ‘taboo’ in the society in which they arose. Both gender and sexuality in the last century have fallen into this category, and as such have been popular subjects for exploration within many science fiction circles and sub-genres, for example in the two closely linked themes of utopia and dystopia. Both have been used to examine the nature and issues surrounding gender and sexuality, although dystopic visions of the future tend towards looking at and analysing the problems, whereas the pastoral utopic vision of society does not see them as problems, and it is only the inevitable foreigner or invader of such a society that views, for example, gender transcendence and homosexuality as abnormal. Japanese science fiction, often realised in the form of manga or anime, very frequently attempts to deal with issues of gender and sexuality within a dystopic, and sometimes a utopic, framework. Within manga in general and particularly shoujo, or girls’ manga, there is a developed interest in ‘alternative’ representations of sexuality and gender. However, this essay will firstly look at the concept of the ‘female’ cyborg within dystopia, focussing on both the manga of Ghost In the Shell, by Masamune Shirow, and its adaptation into anime by Mamoru Oshii, and the differences in the representation of gender in cyborgs between the two versions. After this it will briefly explore various types of utopia, including El Hazard and Tenkuu no Escaflowne, and the representations and challenges to gender within them. Some of the most frequently explored dystopic visions of the world in the last two decades are the cyberpunk texts. These tend to be set in the near future, on earth as opposed to in space, and primarily in an urban technological surrounding of degeneration and decay, in which the cityscape plays an integral part in creating an appropriate space for the characters to move across. Such texts include Akira, Bubblegum Crisis 2040 and Macross Plus, all emerging from the late 1980s and ‘90s wave of Japanese cyberpunk. Both the anime and manga of Ghost In The Shell contain the above elements, as well as, more predominantly, the cyborg, which is an important theme in many feminist and non-feminist science fiction texts. The story centres on a ‘female’ cyborg, Major Kusanagi, an amalgamation of biological and technological material containing a human soul or ‘ghost’. Her cyborg nature 1 and her body of a “female model cyborg” as Masamune Shirow terms it become critical themes throughout the text of both the manga and anime versions, as well as her authority and the abilities granted her by her human makers. Mary Catherine Harper says of the cyborg in context of the interpretations of gender politics: “Especially important… is the figure of the cyborg, part technology and part biology, for this figure stands at the center of a feminist biology, a feminist Alien Other.”1 In non-feminist texts, the ‘female’ cyborg, like the alien, can be seen as either less than or more than human, because it is not composed of entirely human matter. Whether inferior or superior to humans it is, along with the entirely technological robot, the Other. It cannot be viewed as equal in either case with the typically male political and scientific forces that created it. Cadora argues in Feminist Cyberpunk that: “Cyborgs are made possible… by a blurring of three boundaries: between human and machine, between human and animal, and between the real and the unreal.”2 These boundaries pre-empt any possibility that cyborgs can be viewed on an equal footing with their human counterparts; in the ‘human’ world, these boundaries are very clearly drawn. The film version of Ghost In the Shell reinscribes firstly the difference between the cyborg and the human with Kusanagi’s lack of any biological ‘sex’: cyborgs have no genetalia and so are unable to reproduce in the human way: “…We see she is as sexless as a Barbie doll, which serves the demands of the story and of Japanese censorship…”3 However, this also attempts to prevent Kusanagi from being viewed as an eroticized object in terms of her sex. In Shirow’s original manga, on the other hand, female designated cyborgs are equipped with genetalia, which makes them vulnerable in one sense to the male ‘gaze’. It could be said, however, that Kusanagi’s body is eroticized even without genetalia in the animation, as in order to use part of her work equipment – camouflage gear – she must first remove her clothes, allowing the viewer to see her apparently developed ‘female’ form, Harper, Incurably Alien Other…, SFS 1995, pp 403 Cadora, Feminist Cyberpunk, SFS 1995, pp360 3 Newman, Sight and Sound, 1996, pp 39 1 2 2 whereas in the manga the camouflage is in the form of extra clothes, so she is not only literally becoming invisible, she is removing signifiers of her femininity also. Both versions of Ghost In the Shell portray the cyborg as physically superior to humans because of their artificial parts, but there is also a hierarchy amongst cyborgs. Kusanagi is the leader of the military division of cyborgs, thanks to her abilities above and beyond those of any of the male-designated cyborgs: “Her incredible competence at her job and her positioning as the narrative’s central protagonist effectively invert the gender roles conventionally allocated to fictional characters…”4 This is shown particularly in the relationship she has with her back-up and driver, Togusa. Togusa is far less able than Kusanagi, as his body is almost all human, and she is clearly holding a great deal of power over him; he envies her speed, her strength, her intelligence: clearly defying common conventions of narrative, where it is nearly always the male as the central role and in a position of power. In the anime she is cold, precise, and logical, making no mistakes and having all those qualities that are popularly attributed to males within science fiction. Added to this is the collection of guns, weaponry and tanks that she uses, a large amount of phallic imagery that reinforces her masculine role in the world of technology she inhabits. Shirow’s version of Kusanagi is just as competent, but she has more ‘human’ characteristics: she becomes frustrated, irritated, happy and joking within the space of a few pages; Shirow also employs the popular technique of making characters appear more ‘cartoony’ and stylised, more humorous, whenever they feel high irritation or amusement. Kusanagi, in asides, repeatedly mutters “I’m the pretty one!”, as though trying to affirm her own attractiveness and sexuality as a ‘woman’. This is not used in the anime, making Oshii’s Kusanagi seem emotionless, more of a machine. Despite the fact that Kusanagi holds power and leadership over all the military cyborgs, she is ultimately answerable to her makers, who are both human and male. They have the ability to destroy her body and her ghost, and they are her superiors: her commands come from the military leaders, although she carries them out however she sees fit. Even though 4 Silvio, Refiguring the Radical Cyborg…, 1999 3 she has more physical power, more abilities and certainly more intelligence than these men, she does not become liberated until she is able to overcome the supposed gender boundary with the aid of her enemy. Kusanagi’s nemesis, the being known as the ‘Puppet Master’, is also an interesting study in gender. The Puppet Master is a master hacker of the cyber-system that links cyborgs and gives them information, a ‘ghost’ without form. It ‘borrows’ cyborg bodies to aid it in its quest to find a higher type of existence. The Puppet Master takes on a female body, although the voice in the anime inscribes it as male, and intends, and eventually succeeds, to ‘merge’ with Kusanagi to achieve a life - form that is neither male nor female, one that is stronger than both of them; the ‘child’ of this merging will be powerful beyond belief, as gender boundaries are overstepped and all that is combined are the strength and abilities of their two ghosts: “It would seem that this transcendence of the body allows the transcendence of sexual specificity…”5 However, as things do not work out exactly as the Puppet Master planned; the new entity still needs a body, and the one that is provided is that of a young girl, with a girl’s voice, which leads the viewer to think of the ‘child’ as female-designated. This shows that, even with the intended reading that cyborgs are sexless, the body leads us to put male and female values on the characters. Thus we can see that the mixture of technology, biology and the ‘ghost’ have granted Kusanagi unnatural power, but that she is only free to use this power within the jurisdiction of her makers, who are male. The female cyborg is only an equal among her own kind, and the social inequalities of a dystopia remain despite the fact that cyborgs are inhuman and technically ‘higher’ beings. This is further developed in Bubblegum Crisis, where cyborgs, despite their superior physical and mental abilities, are not permitted to hold positions of power, and are employed only for menial work or, in the case of some ‘females’, the sex industry (although it is human women who are attempting to put an end to this). Gender issues in this type of dystopia are not resolved even among the non-human, and the problem is either ignored or exacerbated by the human males controlling society. 5 Silvio, Refiguring the Radical Cyborg…, 1999, pp 61 4 The concept of a utopian society in science fiction, however, deals with gender issues and sexuality in different ways. Gordon says: “Virtually every feminist Science-fiction utopia dreams of a pastoral world, fuelled by organic structures rather than mechanical ones, inspired by versions of the archetypal Great Mother.”6 Feminist utopia or not, manga science fiction versions do tend towards the pastoral in terms of setting; rather than the cityscapes of the dystopia, they are an idyll of the natural world, often with costumes and buildings that lead us to think of an earlier time. This said, it is quite difficult to find any straightforward utopias in manga science fiction, as artists seem to prefer dystopic visions of the future. Utopias are more generally found in the sci-fi / fantasy crossover group. Hiroki Hayashi’s 1992 anime El Hazard: The Magnificent World, and the follow-up manga, is a good example of the pastoral utopia. It is set, as are many Japanese utopias, in another world that can occasionally be reached from Earth – not another planet, but an alternative dimension that allows comparison with the less perfect world that we inhabit. A high school student, Makoto Mizuhara, his inept alcoholic teacher, and his nemesis Jinnai, are mysteriously transported through the dimensions to the world of El Hazard, a place of exotic countryside, ruled by two women. These women, sisters and princesses, command all the power, but there seems no discrimination against gender; males and females hold positions of power with no acrimony. It is a peaceful world that appears to have no problems. However, in order to compare it against something, every utopic vision of the future must be threatened at some point in the narrative. The country neighbouring El Hazard is a technological institution, inhabited mainly by mechanical ‘bugs’ – giant insects that are viewed as male throughout the series, although Jinnai later gives them all female names as a derisive act. What is interesting is that these are led by a woman against El Hazard, and an invasion of the pastoral by the technological takes place. One of the princesses is abducted just before Makoto reaches El Hazard. When he does, it is discovered that he looks identical to the princess, and is forced to impersonate her while she is found. Thus he spends the majority of the series crossdressing, in the process becoming miraculously attractive to both sexes, including the princess’s lover, Alielle. It is shocking only to the visitors from Earth, 5 the ‘foreigners’, that the princess’s lover is a woman, who is extremely sexually active and desires practically every other woman they meet. Thus we see in the utopia that ‘alternative’ sexualities are not even seen as an issue among the inhabitants, and that only the visitors see anything amiss in this or in Makoto’s crossdressing: “Over feminist SF always grapples with the definition of femaleness and at least implies the possibility of a world whose values support a feminist definition of female identity. Covert feminist SF ignores the definition, showing a sexually egalitarian world; furthermore, its values often ignore specifically feminist issues, making its morality a more generally implied one.”7 The latter view of the world is more applicable to El Hazard: gender and sexuality issues are not regarded as issues until the inhabitants of Earth arrive to make them so. We see a different version of gender in Shouji Kawamori’s mecha–fantasy Tenkuu no Escaflowne (Vision of Escaflowne). Again, this involves another world – Gaea – which is intended as a utopia by its inhabitants. It was created, so the story goes, by the people of Atlantis, a historical utopia. It appears to be pastoral and fantastic, and the costumes seem more from a fairytale than futuristic as we commonly see it. Nevertheless, this is once again a utopia threatened by civil war, and its destruction may only be prevented by a girl from Earth, Hitomi Kinzake, who unwittingly possesses psionic powers and the ability to change the course of the future by fortune telling. Unlike El Hazard, however, Escaflowne has a different view of the role of women. Women and girls in Gaea are to be protected by the historical tradition of chivalry. It is seen as the male’s duty to look after females, even those who possess grater power and abilities. This attitude is not contested by the female characters, who appear almost perfectly content with the state of affairs, and regard it as their privilege to be protected in this fashion. It is only Hitomi, the ‘alien’ figure to the inhabitants, who is unhappy with being cared for and protected constantly; she argues that it makes her inferior. This utopia is based on an acceptance that men and women do have different roles. There is no discrimination against women; rather, the discrimination is speciesist, by the humans and beast-people against the 6 7 Gordon, Yin and Yang Duke It Out, Storming the Reality Studio…, 1991, pp 199 Gordon, Yin and Yang …, 1991, pp 196 6 Draconians, the winged descendants of the people of Atlantis. The main male protagonist is Draconian, and it is he more than any of the women who suffer from prejudice. It is interesting that the only place we see females taking on male roles is on the side of the ‘bad guys’, those attempting to destroy the utopia. Here, the most prized fighters are two catgirls, “Intensified Luck Soldiers”, whose extraordinary capabilities allow them the ‘privilege’ of doing a male job. It is on this side, also, that we see tampering with gender and biology. One of the main aggressors, who throughout the whole series has been taken as male, turns out to have been originally female, until his biology was tampered with in order to produce a better fighter. This shows us that in this alternative world, the male is viewed very much as taking on active and aggressive roles, whether as protector or fighter, and the female within the utopia is content to be cared for so that she can use her abilities in safety. Again, this is only an issue worthy of comment by the foreigner. Thus we can see from all this that dystopias and utopias view gender and sexuality issues in very different ways. The urban dystopia of the near future uses the cyborg and the cybernetic world to represent the ‘Other’; because of her differences from human men, the female cyborg can never be represented as a figure of equality with them. There will always be sexual and gender-based discrepancy within a dystopic vision of the future until the nonhuman and the female have stopped being regarded as the ‘other’. Technology can be viewed as a tool of both liberation and oppression. Utopias in general, apart from overt feminist writings, do not view gender and sexuality as an issue. Whether men and women have equal roles, or whether they are unequal, their roles are only seen as problems by the foreigners: the visitors to said utopias from another place. The inhabitants themselves do not attempt to challenge the boundaries of gender, and it could be said that therefore they are not representative of today’s world or society, because in real life we are constantly challenging them. 7 BIBLIOGRAPHY Critical Texts Bergstrom, J., Lyon, E., Penley, C., & Spigel, L., Eds., Close Encounters: Film, Feminism and Science Fiction (Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press LTD, 1988) Cadora, K., Feminist Cyberpunk, Science Fiction Studies vol.22 no.67, 1995 Fernbach, A., The Fetishization of Masculinity in Science Fiction: the Cyborg and the Console Cowboy, Science Fiction Studies vol. 27 no.81, 2000 Harper, M.C., Incurably Alien Other: A Case For Feminist Cyborg Writers, Science Fiction Studies, vol.22 no.67, 1995 Hollinger, V., Doing It For Ourselves: Two Feminist Cyber-readers, Science Fiction Studies, vol.28 no.85, 2001 Lefanu, S., In the Chinks of the World Machine: Feminism and Science Fiction (London, the Woman’s Press LTD, 1988) McCaffrey, L., Ed., Storming the Reality Studio: a Casebook of Cyberpunk and Postmodern Fiction (USA, Duke University Press, 1991) Miller, J., Post-Apocalyptic Hoping: Octavia Butler’s Dystopian/Utopian Vision, Science Fiction Studies, vol.25 no.75, 1998 Moylan, T., Demand The Impossible: Science Fiction and the Utopian Imagination (Methuan, 1986) Newman, K., Ghost In the Shell Review, Sight and Sound, vol.6 no.1, 1996 Schodt, F.L., Manga! Manga! Manga! The World Of Japanese Comics (New York / Japan, Kodansha International LTD, 1983) Schodt, F.L., Dreamland Japan: Writings on Modern Manga (Berkeley, Stone Bridge Press, 1996) Siivonen, T., Cyborgs And Genetic Oxymorons: The Body and Technology in William Gibson’s Cyberspace Trilogy, Science Fiction Studies, vol.23 no.69, 1996 Silvio, C., Refiguring the Radical Cyborg In Mamoru Oshii’s Ghost In The Shell, Science Fiction Studies, vol.26 no.77, 1999 8 Fictional Texts Hayashi, H., Dir., El Hazard: The Mysterious World (Pioneer, 1992) Kawamori, S., Dir., Macross Plus (Manga Entertainment LTD, 1997) Kawamori, S., Dir., Tenkuu no Escaflowne (1999) Oshii, M., Dir., Ghost In The Shell (Manga Entertainment Ltd, 1995) Shirow, M., Ghost In the Shell (Kodansha LTD, Studio Proetus & Dark Horse Comics, 1991) Tsubura, H., El Hazard (Viz Comics, 1996, 2001) 9