Shared Reading Correlates of Early Reading Skills

advertisement

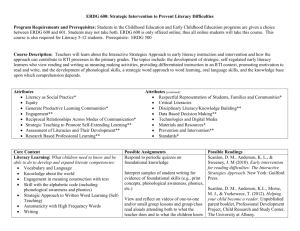

Shared Reading Correlates of Early Reading Skills Stephen Burgess Abstract This article describes a study that examined the relations between shared reading and the development of phonological sensitivity and oral language skills in very young children. Preschool measures of shared reading were found to be correlated significantly with these developmental outcomes, but the magnitude of these relations varied by outcome and measure of shared reading. Results are discussed in the context of calls for improved home literacy environments for young children and their implications for early intervention programs. Introduction Learning to read is a difficult process that involves a number of different skills and experiences. It depends on learning to decode individual words as well as having the necessary knowledge of concepts and the world to comprehend the meaning of the text. According to Carroll, Davies, and Richman (1971) and Adams (1990), children are expected to recognize and understand more than 80,000 words by the end of third grade (at age 8 or 9). However, the process of learning to read starts before school for many children. It is well documented that children enter school differentially prepared to benefit from formal educational experiences and that these differences often translate into subsequent differences in achievement in reading and in other subject areas (e.g., Adams; Wagner, Torgesen, & Rashotte, 1994; Wagner et al., 1997). When asked about the origins of these initial differences, parents, educators, and researchers most commonly cite some aspect of the home literacy environment (HLE) that parents provide for their preschool children. The presumption that exposing children to a home environment rich in literacy activities is beneficial to literacy and language development has come increasingly to influence contemporary educational theory and practice. In the United States, for example, where educators strive to meet the federal mandate that every child read well by the end of third grade, there is a nationwide call for parents to read to their children along with numerous government initiatives to increase children’s exposure to literacy activities (e.g., the America Reads Challenge proposed by former President Clinton, provisions of the Reading Excellence Act supported by Presidents Clinton and Bush). However, despite the almost universal consensus that HLE, especially in the form of shared reading activities, is important in the development of language and literacy skills, evidence suggests that the association between HLE and educational and developmental outcomes is small to modest in size. Scarborough and Dobrich (1994) identified only 31 research samples that examined the relations of shared reading during the preschool years to a variety of tasks designed to assess oral language, literacy-related skills (e.g., letter knowledge), and literacy achievement measured during preschool or later school years. A similar number of studies (29) was identified by Bus, van Ijzendoorn, and Pelligrini (1995) in their review of the effectiveness of shared reading in the preschool years. The authors of both reviews concluded that individual differences in preschool exposure to shared reading explained approximately 8 percent of the variance in the academic outcomes studied, with a median correlation of .26 reported by Scarborough and Dobrich. This is an area in need of additional research and clarification. Early studies of the HLE’s influence tended to reduce its complexity to social status measures (e.g., parental education, occupation, income). It was generally found that children from lower socioeconomic status (SES) and non-mainstream cultural communities performed less well on reading tests and demonstrated lower levels of interest in literacy (e.g., Dickinson & Snow, 1987; Teale, 1986). However, social status is a marker variable that represents a number of attitudes, activities, and opportunities and does not identify the specific aspects of the home environment that are important in different stages of literacy and language development. More recently, researchers have sought to identify these specific aspects that relate to literacy and language development. It has been found that certain aspects of the HLE, especially shared reading activities, explain more adequately the relation between home environment and educational and developmental outcomes than do more global social class measures (e.g., Iverson & Walberg, 1982; Share, Jorm, Maclean, & Matthews, 1984; Walberg & Tsai, 1985; White, 1982). Lonigan (1994) and Scarborough and Dobrich (1994) suggested that future researchers attempt to take into account that different aspects of HLE may exert their influence on different outcomes and that the relative importance of HLE may vary by outcome and developmental period. For example, shared reading may influence oral language development, whereas letter knowledge may come from more direct parental instruction. Senechal, LeFevre, Thomas, and Daley (1998, online document) found that storybook exposure accounted for a statistically significant amount of unique variance in kindergarten and Grade 1 children’s oral language skills, but not in their written language skills. In contrast, a measure of parental teaching (e.g., number of instances a parent taught a child to read words and to print words in a typical week) explained statistically significant unique variance in children’s written language skills, but not in their oral language skills. Other researchers have also found that different aspects of HLE influence different outcomes (e.g., Meyer, Stahl, Wardrop, & Linn, 1994; Whitehurst, Arnold, Epstein, Angell, Smith, & Fischel, 1994). In order to extend our understanding of the potential role of the preschool HLE in the development of individual differences in language and literacy development, studies are needed to test the relations of different aspects of the HLE with a variety of ageappropriate developmental outcomes (Dunning, Mason, & Stewart, 1994; Ehri & Sweet, 1991; Hess, Hollaway, Dickson, & Price, 1984; Hiebert, 1980; Lonigan, 1994; Whiteurst & Lonigan, 1998). These studies should directly address how particular features of family experience map onto children’s developing components of language and literacy at various stages. The present study examined the relations of shared reading to oral language, represented by receptive and expressive vocabulary and phonological sensitivity. These outcomes were selected because of their importance in the development of literacy-related skills during the preschool years; later, more complex literacy skills in alphabetic languages; and eventual success in school. They are well-established precursors of individual differences in word reading and comprehension development (e.g., Adams, 1990; Senechal et al., 1998; Wagner, Torgesen, & Rashotte, 1994). Vocabulary knowledge is necessary for reading comprehension (e.g., Juel, 1994; Stanovich, 1986). Phonological sensitivity refers to sensitivity to and ability to manipulate the sound structure of oral language. Children who are better at detecting and manipulating syllables, rhymes, or phonemes are quicker to learn to read, and this relation is present even after variability in reading skill due to factors such as intelligence quotient, receptive vocabulary, memory skills, and social class is partialled out (e.g., Bryant, MacLean, Bradley, & Crossland, 1990; Wagner, Torgesen, & Rashotte, 1994). Phonemic awareness (often called phonological awareness) is the ability to manipulate the individual phonemes within words and is considered to be the most complex or most developed stage of phonological sensitivity (e.g., Adams). Recent studies have demonstrated that individual differences in phonological sensitivity are relatively stable across time from late preschool (e.g., Byrne, Freebody, & Gates, 1992; Lonigan, Burgess, & Anthony, 2000; Wagner, Torgesen, & Rashotte), and that individual differences in preschool levels of phonological sensitivity are related to subsequent individual differences in literacy development (e.g., Lonigan, Burgess, & Anthony). However, despite the importance of phonological sensitivity to the emergence of literacy skills, little is known about the relation of HLE to its development (e.g., Burgess, 1999). Questions concerning the HLE and its relation to different educational and developmental outcomes are important for several reasons. First, the call for parents and schools to provide more and better literacy resources for children has become an educational priority, but we have a relatively poor understanding of the factors within the HLE that explain its influence on literacy’s development and maintenance over time or of the specific aspects of the HLE that are important at different developmental stages for a variety of educationally relevant outcomes (e.g., letter knowledge, phonological sensitivity) (Burgess & Lonigan, 1997; Debaryshe, 1995; Senechal et al., 1998). Therefore, in order to design more effective and long-lasting interventions, more research on the HLE is needed (Debaryshe; Leseman & de Jong, 1998, online document). Second, in order to develop models of the development of literacy and language outcomes that incorporate the influence of the HLE, more studies are required to untangle the web of correlations among elements of the HLE and the various developmental and educational outcomes researchers have examined. Overview of the Study The study described in this article sought to extend earlier work on the relationship between the preschool HLE and developmental and educational outcomes related to early literacy acquisition. More specifically, the relations between shared reading and oral language and phonological sensitivity were examined in 115 four- and five-yearold children from middle-income homes. Information regarding HLE was obtained via a survey completed by parents. It was expected that shared reading would be significantly related to language and phonological sensitivity but that the relation would vary by developmental outcome. Methods Participants. The participants were 115 four- and five-year-olds (mean age, 60.4 months; SD = 5.41; range, 48 to 70 months) recruited from childcare centers serving predominately middle-class families for a larger longitudinal study exploring the development of phonological sensitivity. Only those children for whom home literacy environment data were available were included in the analyses (N=97). The sample consisted of approximately equal numbers of boys and girls. The children were all from middle-class families, as established by Hollingshead’s (1975) Four Factor Index. This index combines parental occupation and education level to estimate socioeconomic status. Procedure. After the researchers obtained informed consent from parents, children were tested individually by trained research assistants in their childcare centers. Test administration for individual children was conducted over two to four sessions within a 2-week period to ensure optimal performance on all tasks. Children completed two standardized tests of oral language and four tests of phonological sensitivity. The HLE was assessed via a survey completed by parents. Oral language measures. The grammatical closure subtest of the Illinois Test of Psycholinguistic Abilities (Kirk, McCarthy, & Kirk, 1968) requires the child to provide a grammatically correct word to complete a sentence prompt that describes a sequence of two pictures. This test was used as an estimate of children’s expressive language abilities. The grammatical understanding subtest of the Test of Language Development--Primary (Newcomer & Hammill, 1991) requires children to select the correct picture out of three possible choices that corresponds to a sentence spoken by the examiner. This test was used as an estimate of children’s receptive language abilities. Phonological sensitivity measures. Four tasks were used to assess different aspects of children’s phonological sensitivity. Previous analyses of these four tasks indicated that they have moderate to high internal consistencies for young children (Lonigan et al., 1998; Wagner, Torgesen, & Rashotte, 1994) and are predictive of subsequent phonological sensitivity and word-reading abilities (Burgess & Lonigan, 1998; Lonigan, Burgess, & Anthony, 2000). Previous analyses also indicated that different word units (i.e., word, syllable, phoneme level) are best described by a single phonological sensitivity factor (Lonigan, Burgess, & Anthony; Wagner, Torgesen, & Rashotte). A rhyme oddity detection task, patterned after the task developed by MacLean, Bryant, and Bradley (1987) and using their word list, required children to demonstrate awareness of rhyme. Children were presented with three pictured words (e.g., boat, nail, sail) and were asked to select the one that did not rhyme with (or that sounded different from) the other two. Two practice trials and 11 test trials were presented to all children. Corrective feedback was given during the practice trials, but no feedback was given during the practice trials. Internal consistency at Time 1 (alpha = .71) was moderate. An alliteration oddity detection task, also patterned after the task developed by MacLean, Bryant, and Bradley (1987), using their word list, required children to demonstrate awareness of singleton word onsets. Children were presented with three pictured words (e.g., car, cat, sun) and were asked to select the one that did not sound the same at the beginning (or that sounded different) at the beginning of the word as the other two. Two practice trials and eleven test trials were presented to all children. Corrective feedback was given during the test trials. Internal consistency at Time 1 was moderate (alpha = .68). A blending task, patterned after the task used by Wagner, Torgesen, and Rashotte (1994), required children to combine word elements to form a word. Three practice items and the first eight trials were presented both verbally and with pictures; the remaining test trials were presented verbally only. In both picture [view 288K video clip] and nonpicture trials, the first five items required blending single-syllable words to form compound words, and the remaining items required blending syllables or phonemes. For picture items involving compound words, the examiner showed the child two pictures and named them (e.g., “This is a cow and this is a boy”) and then asked the child what word would be produced if you said them together (e.g., “What do you get when you say ‘cow’ and ‘boy’ together?”). All practice items required the blending of compound words, during which the experimenter emphasized the nature of the task by physically putting the picture together while presenting the trial. Practice items were followed by correction, explanation, and readministration (up to three times) if the child did not produce the correct response, and confirmation and explanation if the child provided the correct answer. There was no feedback on the test trials. There were 18 test trials, consisting of 10 word-blending items, 4 syllable-blending items, and 4 phonemeblending items. Testing was discontinued after a child missed five consecutive trials. The internal consistency of the task was high (alpha = .91). An elision task, also patterned after a task used by Wagner, Torgesen, & Rashotte (1994), required children to say a word minus a specific sound. Two practice items and the first eight test trials were presented both verbally and with pictures; the remaining test trials were presented verbally only. In both picture [view 400K video clip] and nonpicture trials, the first four items required deleting a single-syllable word from a compound word to form a new word. Subsequent items in both picture and nonpicture trials required deletion of a syllable or a phoneme from a word to form a new word. Both practice items used compound words. For picture items involving compound words, the examiner showed the child two pictures and named them (e.g., “This is a bat, and this is a man”) and then asked the child to say the compound (i.e., “batman”) prior to being asked to delete part of it. During practice trials, the examiner emphasized the nature of the task by physically removing the picture of the word to be deleted. Practice trials were followed by correction, explanation, and readministration (up to two times) if the child did not produce the correct response, and confirmation and explanation if the child provided the correct answer. There was no feedback on the test trials. There were 15 test trials, consisting of 8 word-level items, 4 syllable-level items, and 3 phoneme-level items. Testing was discontinued after a child missed five consecutive trials. Internal consistency of the task was high (alpha = .88). Home Literacy Environment Questionnaire. The HLE was assessed via parental responses to a written questionnaire. The questionnaire was designed to assess a wide range of elements of the HLE (e.g., family demographics, parental leisure reading habits, family storybook reading habits) and was patterned after the survey developed by Whitehurst and colleagues (e.g., Payne, Whitehurst, & Angell, 1994). Social class information was detailed with questions about family income, parental occupation, and parental educational level. The shared reading patterns of the family were described by questions asking parents to estimate the number of children’s books in the home, the age at which they first read to their child, and the current frequency and duration of shared reading episodes. Results Preliminary examination of the data indicated that some variables deviated from normality (e.g, elision scores were negatively skewed). Transformation of these variables (see Tabachnick & Fidell, 1989) improved their distributions but did not change the pattern of correlations between variables or the pattern of results for the correlation or multiple regression analyses reported below. Therefore, all analyses were carried out using the untransformed variables. The number of child variables was reduced by forming unit-weighted composite variables for phonological sensitivity and oral language. Each composite variable was created by averaging the standard scores of the relevant variables (e.g., the phonological sensitivity composite was the average of the four z-scored transformed phonological sensitivity tasks). The use of unit-weighted composite variables does not eliminate task-specific variance to the same extent as latent variables; however, it does reduce the possibility that estimates of relations in regression analyses will be specific to one particular set of stimulus materials or method of measurement (Torgesen, Wagner, Rashotte, Burgess, & Hecht, 1997). The HLE variables were scaled such that higher z-scores represented more desirable outcomes. For example, a lower age of first shared reading experience would be more desirable. This was done to take into account the likely negative correlations between some variables (e.g., shared reading onset and oral language). The children attended seven different childcare centers. No formal observational data were collected regarding the educational activities the centers provided the children, but the activities varied in terms of the number of educational materials available and the willingness of the staff to engage in activities such as shared reading. A separate series of analyses were also conducted to determine if the observed results were due in part to differences in the educational experiences the children received in their childcare environments. Controlling for the center attended did not alter the pattern of results reported in the following analyses. Descriptive statistics. Descriptive statistics for age and the measures of phonological sensitivity, oral language, and the HLE are shown in Table 1. There was substantial variability in all the measures for this age group. These results indicate that, despite their young age, the children were able to perform the phonological sensitivity tasks. Parents reported a wide range of literacy experiences and their responses indicated that, for many children, shared reading activities were an established and frequent part of the home routine. For example, parental reports of children’ age at the first shared reading ranged from birth to 18 months, with an average of 7.3 months; parents reported a range of 5 to 500 children’s books in the home, with an average of 137.8 (SD = 92.8). Table 1 Means, Standard Deviations (SD), and Ranges for Children’s Ages and Indices of Phonological Sensitivity, Oral Language, and Home Literacy Environment (HLE) (N=97) Variable Mean SD Range (min.max.) Chronological age (months) 60.4 5.41 48-70 Phonological sensitivity (%)a 58.9 18.58 16-98 Rhyme oddity 6.49 2.75 1-11 Alliteration oddity 5.46 2.64 0-11 Blending 12.22 5.03 0-18 Elision 8.87 4.21 0-15 Grammatical understandingb 10.7 2.78 3-16 Grammatical closureb 43.01 10.03 21-66 Age first read to (months) 7.32 4.48 0-18 No. children’s in home 137.75 92.85 5-500 Shared reading frequency (no. times per week) 5.71 2.35 2-14 Shared reading duration (no. minutes per week) 146.64 89.31 15-420 48.01 7.13 30.5-66.0 Oral language HLE Hollingshead (1975) indexc Average percent correct on the four phonological sensitivity tasks. Standard scores from tabled values. c Composite index of socioeconomic status combining levels of parental education and occupation. a b Bivariate correlations. Correlations between HLE and measures of oral language and phonological sensitivity are shown in Table 2. The correlations varied extensively in magnitude across, as well as within, the different outcomes examined. The average correlation for the oral language composite with the different measures used was .25, with three of the five relations significant. The average correlation was .20 for the measure of receptive vocabulary and .19 for expressive vocabulary, with three of the five relations significant in each case. The average correlation of the home environment with phonological sensitivity was .16, with only the estimate of first age read to being significant. The finding that socioeconomic status was not significantly related to these outcome measures was not completely unexpected given the predominately middle-class nature of the sample. The magnitude of the correlations between the home environment and the two measures of oral language found in the present study was similar to those obtained in the reviews conducted by Scarborough and Dobrich (1994) and Bus, van Ijzendoorn, and Pelligrini (1995). Table 2 Correlations of Measures of Phonological Sensitivity, Oral Language, and Shared Reading (N=97) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1. Phonological sensitivity 2. Oral language composite .50** --- 3. Receptive vocabulary .31** .78*** --- 4. Expressive vocabulary .53** .66*** .21* --- No. of children’s books .18 6. Age at onset of shared reading .32** .32** .25* .25* .26* 7. Shared reading frequency .16 .29** .27* .23* .36** .40** --- 8. Shared reading duration .03 .10 .05 .10 .23* .32** .53** --- 9. Socioeconomic status .12 .17 .14 .05 .19 .19 .19 .10 --- 10. Age .39** --- --- --- .04 .01 .08 .00 .05 --- .36** .26* .31** ----- *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001 Multiple regression analyses. Multiple regression was used to determine the extent to which individual differences in the preschool HLE explained individual differences in the measures of oral language and phonological sensitivity. Separate sets of regression analyses were conducted for oral language and phonological sensitivity. In each model, chronological age and socioeconomic status were entered first and then the shared reading variables were entered in the second step. See Table 3 for the results of the multiple regressions. Table 3 Regression of Shared Reading Measures on Language Ability and Phonological Sensitivity (N=97) Dependent Variable Predictor Step Age 1 Oral Language Receptive Vocabulary Expressive Vocabulary Phonological Sensitivity -.04 -.02 .03 .39** .06 .06 -.04 .04 .26* .19 .22* .09 Age at onset of shared reading -.22* -.18 -.16 -.31* Shared reading frequency .16 .04 .20 .09 Shared reading duration -.12 -.03 -.16 -.20 R2 change for step 2 14.6% 8.3% 14.4% 12.6% Total R2 15.6% 10.7% 16.3% 29.3% Socioeconomic status Step No. of children’s 2 books * < .05, ** < .01 For the oral language composite, the addition of the shared reading variables added 14.6 percent explained variance to the model. The number of children’s books in the home and the age at onset of shared reading were the only significant unique predictors. When the oral language measures were examined individually, the shared reading variables added 8.3 percent explained variance to the prediction of the measure of receptive vocabulary, but none of the individual predictors was significant. The addition of the shared reading variables added 14.4 percent unique variance to the prediction of the measure of expressive vocabulary, with the number of children’s books the only significant unique predictor. For the phonological sensitivity composite, the addition of the shared reading variables added 12.6 percent explained variance to the model. Age at onset of shared reading and age were the only significant unique predictors. The bivariate correlations and multiple regression results indicate that shared reading is associated with oral language and phonological sensitivity development in this subject sample, but that the magnitude of this relation depends on the manner in which shared reading was conceptualized and the particular outcome examined. For example, the measures of shared reading which more closely tapped the longterm nature of the home environment, such as the number of children’s books in the home and the age at onset of shared reading, were more highly associated with the developmental outcomes assessed in this study. Discussion Literacy acquisition is thought to start at an early age, long before formal reading instruction begins. An early introduction to books and participation in literacy and literacy-related activities with parents are seen as important in the preparation of children for school-based formal instruction. There are differences in the home literacy environments provided by families and thus, in the preparation of children for school learning (e.g., Neuman & Celano, 2001, online document). The present study highlights the importance of early and sustained shared reading experiences in the development of oral language and phonological sensitivity in young children. This study adds to the growing body of evidence demonstrating that early exposure to literacy in the form of shared reading is related to educational and developmental outcomes (e.g., Bus, van Ijzendoorn, & Pelligrini, 1995; Koskinen, Blum, Bisson, Phillips, Creamer, & Baker, 2000). It extends previous research by including multiple measures of shared reading and books as well as multiple measures of language outcomes thought to be important to the development of literacy. Results of the study indicate that shared reading is related to language outcomes in preschool-aged children and that the magnitude of the relation varies by the manner in which shared reading is measured and language outcome assessed. The shared reading variables were significantly related to the oral language composite, expressive and receptive vocabulary, and phonological sensitivity. This finding is important because it demonstrates that shared reading is associated with a variety of language outcomes and not just with variables such as environmental print and letter knowledge. This is one of the first studies to demonstrate a relationship between phonological sensitivity and shared reading. As mentioned previously, deficits in phonological sensitivity are thought to be most significant factor for most children having difficulty learning to read (e.g., Wagner, Torgesen, & Rashotte, 1994). Future studies designed to explore the role of shared reading in the development of phonological sensitivity are needed. In addition, the present study examined a sample of families from predominately middle-class homes. Therefore, the results must be interpreted with caution until studies are undertaken with families from more diverse social and economic backgrounds. Interestingly, measures of shared reading were more likely to be significantly related to the outcomes when they took into account more cumulative than concurrent aspects of shared reading. For example, the earlier a child is read to, the more likely he or she is to be exposed to a greater number of shared reading episodes over time. The cumulative measures may reflect a greater emphasis on literacy behaviors over time in the home than the concurrent measures. The concurrent measures may fluctuate more freely with activities that compete for time in the family (e.g., work, seasonal sports) and thus be a poorer and less consistent estimate of the overall quality of the literacy environment of the child (e.g., Debaryshe, 1995). The continued examination of the relations between shared reading and other home literacy variables with educational outcomes is necessary for several reasons. First, the growing demand for parental participation in the educational process is reflected in the widespread call for parents to read more to their children. This begs the question of how parental time and effort is best expended. We need continued examination of the kinds of activities parents engage in with children and which outcomes they influence. A number of studies have documented that specific shared reading practices effect vocabulary and other reading-related skill development (e.g., Murray, Stahl, & Ivey, 1996; Whitehurst et al., 1994). For example, Murray, Stahl, and Ivey found that parents’ reading of alphabet books to children was associated with children’s gains in phonological sensitivity. This is consistent with the idea that letter knowledge aids in the development of phonological sensitivity (e.g., Burgess & Lonigan, 1998). Others have suggested specific books that may develop readingrelated skills such as phonological awareness (e.g., Opitz, 1998). More attention has to be given to educating parents, those asked by educators and politicians to put these practices into place. Second, if programs designed to increase literacy levels by manipulating some aspect of the home literacy environment are to be effective, we need to understand not only which aspects of the environment to manipulate but also why parents provide the kinds of environments they do (e.g., Leseman & de Jong, 1998). For example, there a number of possible reasons why a parent may not read to a child: perhaps he or she is not comfortable reading aloud, or does not have easy access to literacy materials. Therefore, changing the home environment may require more than merely an understanding that it relates to certain outcomes; it may require an understanding of the complex factors that determine the literacy environment’s development and maintenance. A recent analysis of family literacy programs emphasized a need to include social and cultural factors in programs designed to encourage literacy activities in the home (Neuman, Caperelli, & Kee, 1998). Therefore, as mentioned previously, we must examine how to put into practice most effectively the shared reading methods that have been shown to improve readingrelated skills. In conclusion, this study adds to the growing body of evidence suggesting that the home environment of young children is important in the educational process. It extends prior research by including phonological sensitivity and multiple measures of language development. I now join in the call for a greater emphasis on educating parents on the specific methods they can use in the home to better prepare children to benefit from the formal educational environment. I also add a note of caution: merely asking parents to read may not be enough. We need to better understand the motivators within the home environment so educators can provide parents the knowledge and resources which will increase the effectiveness of parental practice as well as the likelihood that parents will continue the targeted behaviors. References Adams, M.J. (1990). Beginning to read: Thinking and learning about print. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Bryant, P.E., MacLean, M., Bradley, L.L., & Crossland, J. (1990). Rhyme and alliteration, phoneme detection, and learning to read. Developmental Psychology, 26, 429-438. Burgess, S.R. (1999). Parental characteristics that predict children’s home literacy environment. Poster presented at the annual meeting of the Southwestern Psychological Association, Albuquerque, NM. Burgess, S.R., & Lonigan, C.J. (1997, March). A meta-analysis examining the influence of the home literacy environment on early reading development: Paper lion or king of the reading jungle. Paper presented at a meeting of the Society for the Scientific Study of Reading, Chicago, IL. Burgess, S.R., & Lonigan, C.J. (1998). Bidirectional relations between phonological awareness and reading extended to preschool letter knowledge: Evidence from a longitudinal investigation. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 70, 117-141. Bus, A.G., van Ijzendoorn, M.H., & Pelligrini, A. (1995). Joint book reading makes for success in learning to read: A meta-analysis on intergenerational transmission of literacy. Review of Educational Research, 65, 1-21. Byrne, B., Freebody, P., & Gates, A. (1992). Longitudinal data on the relations of word-reading strategies to comprehension, reading time, and phonemic awareness. Reading Research Quarterly, 27, 141-151. Carroll, J.B., Davies, P., & Richman, B. (1971). Word frequency book. New York: American Heritage. Debaryshe, B.D. (1995). Maternal belief systems: Linchpin in the home reading process. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 16, 1-20. Dickinson, D.K., & Snow, C.E. (1987). Interrelationships among prereading and oral language skills in kindergarten from two social classes. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 2, 1-25. Dunning, D.B., Mason, J.M., & Stewart, J.P. (1994). Reading to preschoolers: A response to Scarborough and Dobrich (1994) and recommendations for future research. Developmental Review, 14, 324-339. Ehri, L.C., & Sweet, J. (1991). Fingerpoint-reading of memorized text: What enables beginners to process print? Reading Research Quarterly, 26, 442-463. Hess, R.D., Hollaway, S.D., Dickson, W.P., & Price, G.G. (1984). School readiness and later achievement in vocabulary and mathematics in sixth grade. Child Development, 55, 1902-1912. Hiebert, E.H. (1980). The relationship of logical reasoning ability, oral language comprehension, and home experiences to preschool children’s print awareness. Journal of Reading Behavior, 12, 313-324. Hollingshead, A.B. (1975). Four factor index of social issues. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Iverson, B.K., & Walberg, H.J. (1982). Home environment and school learning: A qualitative synthesis. Journal of Experimental Education, 50, 144-151. Juel, C. (1994). Learning to read and write in one elementary school. New York: Springer-Verlag. Kirk, S.A., McCarthy, J.J., & Kirk, W.D. (1968). Illinois test of psycholinguistic abilities. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. Koskinen, P.S., Blum, I.H., Bisson, S.A., Phillips, S.M., Creamer, T.S., & Baker, T.K. (2000). Book access, shared reading, and audio models: The effects of supporting the literacy learning of linguistically diverse students in school and at home. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92, 23-36. Leseman, P.P., & de Jong, P.F. (1998). Home literacy: Opportunity, instruction, cooperation and social-emotional quality predicting early reading achievement. Reading Research Quarterly, 33, 294-319. Available: www.catchword.com/ira/00340553/v33n3/contp1-1.htm Lonigan, C.J. (1994). Reading to preschoolers exposed: Is the emperor really naked? Developmental Review, 14, 303-323. Lonigan, C.J., Burgess, S.R., & Anthony, J.A. (2000). Development of emergent literacy and reading skills in preschool children: Evidence from a latent variable longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 36, 596-613. Lonigan, C.J., Burgess, S.R., Anthony, J.L., & Barker, T.A. (1998). Development of phonological sensitivity in 2- to 5-year-old children. Educational Psychology, 90, 294311. MacLean, M., Bryant, P., & Bradley, L. (1987). Rhymes, nursery rhymes, and reading in early childhood. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 33, 255-281. Meyer, L.A., Stahl, S.A., Wardrop, J.L., & Linn, R.L. (1994). The effects of reading storybooks aloud to children. Journal of Educational Research, 88, 869-884. Murray, B.A., Stahl, S.A., & Ivey, M.G. (1996). Developing phoneme awareness through alphabet books. Reading & Writing, 8, 307-322. Neuman, S.B., Caperelli, B.J., & Kee, C. (1998). Literacy learning, a family matter. Reading Teacher, 52, 244-252. Neuman, S.B., & Celano, D. (2001). Access to print in low-income and middleincome communities: An ecological study of four neighborhoods. Reading Research Quarterly, 36, 8-26. Available: www.catchword.com/ira/00340553/v36n1/contp11.htm Newcomer, P.L., & Hammill, D.D. (1991). Test of language development--primary (2nd ed.). Austin, TX: ProEd. Opitz, M.F. (1998). Children’s books to develop phonemic awareness -- for you and parents, too! Reading Teacher, 51, 526-528. Payne, A.C., Whitehurst, G.J., & Angell, A.L. (1994). The role of the home literacy environment in the development of language ability in preschool children from lowincome families. Early Child Research Quarterly, 9, 427-440. Scarborough, H.S., & Dobrich, W. (1994). On the efficacy of reading to preschoolers. Developmental Review, 14, 145-302. Senechal, M., LeFevre, J., Thomas, E.M., & Daley, K.E. (1998). Differential effects of home literacy experiences on the development of oral and written language. Reading Research Quarterly, 33, 96-116. Available: www.catchword.com/ira/00340553/v33n1/contp1-1.htm Share, D.L., Jorm, A.F., Maclean, R., & Matthews, R. (1984). Sources of individual differences in reading acquisition. Journal of Educational Psychology, 76, 1309-1324. Stanovich, K.E. (1986). Matthew effects in reading: Some consequences of individual differences in the acquisition of literacy. Reading Research Quarterly, 21, 360-407. Tabachnick, B.G., & Fidell, L.S. (1989). Using multivariate statistics (2nd ed.). New York: HarperCollins. Teale, W.H. (1986). Home background and young children’s literacy development. In W.H. Teale & E. Sulzby (Eds.), Emergent literacy: Writing and reading. Norwood, NJ: Ablex. Torgesen, J.K., Wagner, R.K., Rashotte, C.A., Burgess, S.R., & Hecht, S.A. (1997). Contributions of phonological awareness and rapid autonomic naming ability to the growth of word-reading skills in second- to fifth-grade children. Scientific Study of Reading, 2, 161-185. Wagner, R.K., Torgesen, J.K., & Rashotte, C.A. (1994). Development of readingrelated phonological processing abilities: New evidence of bidirectional causality from a latent variable longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 30, 73-87. Wagner, R.K., Torgesen, J.K., Rashotte, C.A., Hecht, S.A., Barker, T.A., Burgess, S.R., Donahue, J., & Garon, T. (1997). Changing relations between phonological processing abilities and word level reading as children develop from beginning to skilled readers: A 5-year longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 33, 468479. Walberg, H.J., & Tsai, S. (1985). Correlates of reading achievement and attitude: A national assessment study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 78, 159-167. White, K.R. (1982). The relation between socioeconomic status and academic achievement. Psychological Bulletin, 91, 461-481. Whitehurst, G.J., Arnold, D.H., Epstein, J.N., Angell, A.L., Smith, M., & Fischel, J.E. (1994). A picture book intervention in daycare and home for children from lowincome families. Developmental Psychology, 30, 679-689. Whitehurst, G.J., & Lonigan, C.J. (1998). Child development and emergent literacy. Child Development, 69, 848-872.