PYGMY RABBIT - Center for Science in the Public Interest

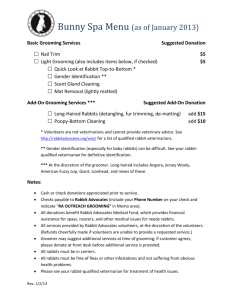

advertisement