Autism and Affect: An Exploration of Emotionally Disordered

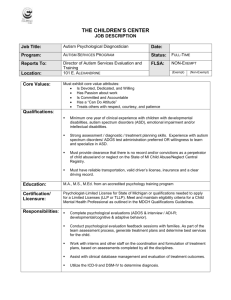

advertisement

Joyce Davidson Draft only “More labels than a jam jar…” The Gendered Dynamics of Diagnosis for Girls and Women with Autism Draft only Joyce Davidson Department of Geography Mackintosh-Corry Hall Queen's University Kingston, Ontario Canada, K7L 3N6 Email – joyce.davidson@.queensu.ca 1 Joyce Davidson Draft only “More labels than a jam jar…” The Gendered Dynamics of Diagnosis for Girls and Women with Autism1 Abstract The term autism, coined by Bleuler in 1911, derives from the Greek autos (meaning ‘self’) – it connotes separation, aloneness - and descriptions of those diagnosed with Autistic Spectrum Disorders (ASDs) frequently suggest they are very much apart from the shared, experientially common space of others. The subjects of clinical literature are very often male children, perhaps unsurprising given the recognized need for early intervention, and the fact that studies suggest four times as many boys receive an ASD diagnosis as girls. This understandable bias does however mean that a significant minority are often overlooked, and this paper focuses on the experience of those girls and women who frequently struggle to obtain diagnosis and treatment for a predominantly male – and thus for them, contested - disorder. Drawing particularly on autobiographical accounts – including the narratives of Temple Grandin, Dawn Prince Hughes and Donna Williams – the paper reveals a strongly felt need to communicate and thus connect their unusual spatial and emotional experience with others, in a manner not typically associated with autism. It explores the gendered dynamics of diagnosis and complex challenges of ASD life-worlds, and the ways in which ASD women use social and spatial strategies to cope with and contest the expectations and reactions of neuro-typical others.2 Introducing Autistic Experience It is well known that individuals with autism and autistic spectrum disorders (ASDs) experience and express involvement with the world in a way that is not ‘typical’, and published accounts imply such different social and spatial dynamics that they might be 2 Joyce Davidson Draft only thought to imply an ‘other’ world. The author of a recent text for family and carers writes that ASD individuals “live in a mysterious world of direct perception and immediacy; they see a world without metaphors […and understanding this world] means traveling to a ‘foreign country’ and learning a new language.” (Szatmari 2004: viii) Jacket reviews of the text claim that it takes the reader on “a journey through uncharted terrain”, and such metaphors of exploration highlight a powerful sense of separation between the world of the familiar, the taken-for-granted and everyday, and ASD worlds that, as this author states, “revolve around a different axis” (Szatmari 2004: 16). Szatmari suggests that understanding this alien land requires work of an imaginative as well as explorative nature: he says, “the ASDs are so mysterious, the behaviours seemingly so inexplicable. It takes a feat of imagination to leap across the boundary of our mind to the mind of the child with autism.” (2004: xi) In this paper, I want to suggest that a spatially sensitive interpretation of ASD women’s own narratives – that is, re-presentations drawn from autobiographical literature - might help facilitate that leap. It may thus further understanding of the production and experience of contested emotion and space, and provide insights into the gendered dynamics of diagnosis. This preliminary study of textual characterizations of ASD is motivated by a feminist social and health geographer’s compulsion to understand something of the quality and extraordinary variety of women’s embodied, and somehow disordered, emotional encounters with the world, an interest emerging initially from experience of panic and subsequent study of its role in agora and other overwhelmingly ‘feminine’ phobias. I’ve felt, in other words, that the material substance of the world shapes and is shaped by emotion – the phobic object ‘causes’ fear, but fear ‘makes’ the world a more frightening place. The emotional texture of our lives is thus continually reconstituted through dynamic interaction across shifting boundaries between people and places, and I want to begin to investigate the possible relevance and resonance that such geographical insights might have for understanding diagnosis, experience and treatment of women with ASDs. The text-based qualitative approach to the subject matter differs considerably from the intensive involvement with individuals and groups that has characterized the majority of 3 Joyce Davidson Draft only my own and others’ work on emotional disorder (Bankey 2001; Davidson 2003; Parr 1999). Empirical reliance on the written rather than spoken word may, at first glance, seem less appropriate for the conduct of explicitly feminist research (Moss 2003). It is, clearly, communication at a distance, both materially and metaphorically. Almost by definition, it allows less space for the development and expression of personal involvement and empathetic interaction. However, I would argue that this method is in fact uniquely suitable for research on ASD experience, a conclusion supported by ‘participants’ themselves.3 Gunilla Gerland (2003: 53) for example, writes in her autobiography that “[e]xpressing words in writing was much easier for me than taking the long way round, as I experienced it, via speech.”4 Dawn Prince-Hughes, in the preface to an edited collection of ‘personal stories of college students with autism’, is similarly emphatic about the limitations of speech, and repeatedly states that writing is the best way for an autistic person to communicate: “It allows time to form one’s thoughts carefully, it has none of the overwhelming intensity of face-to-face conversation, and it affords the writer space to talk about one question or thesis without limit” (2002: xiii). Stressing a perceived need among ASD individuals for research on their experience, she refers to writings in the anthology as self-produced “ethnographic narratives” containing “their truth. Our truth”. Such “autistic autobiography is rare”, she states, “and in my opinion valuable” (Prince-Hughes 2002: xi): “There is simply no way for nonautistic people to gather this kind of information through questionnaires or interviews, or through reading what nonautistic people have said about us” (Prince-Hughes 2002: xiv). The view that insufficient and / or inappropriate research has taken place on ASD women’s experience is relatively common in writings I’ve encountered, as is the sense that there are right and wrong ways to address this absence. In the introduction to Women From Another Planet: Our Lives in the Universe of Autism, Jean Kearns Miller (2003: xxiii) writes: “Given the relative inattention of the research community to women with AS and our own dismay at the inadequacy of diagnostic description, especially as it pertains to women, we began the process of self-definition through interaction with each other… We were, in effect, observer-participants in our own ethnography.”5 The women involved in the project explicitly challenge the reader to “look beyond the clinical 4 Joyce Davidson Draft only contours of their experience”, and I aim to take seriously this invitation and recommendation from insider experts in the account that follows. I hope eventually to engage some of the authors in discussion about my outsider interpretations of their autoethnographies.6 However, for the time being at least, I feel relatively comfortable in ‘using’ their words, for a purpose I imagine most would approve of; namely, the attempt to communicate and further understanding of their personal and often painful experience. Highlighting these minority reports of an overwhelmingly male disorder (see below) does however demand a degree of background involvement with the largely masculinist - and so alien and alienating – body of clinical literature. Clinical Contours and Beyond The term autism, coined by Bleuler in 1911 (Stanghellini 2001) derives from the Greek autos (meaning ‘self’) – it connotes separation, aloneness - and in fact, one of the most common complaints of parents seeking diagnosis is that their child acts as if “in a world of his own” (Daley 2004: 1327), descriptions that suggest the child is very much apart from the shared, experientially common space of others. The male pronoun used in clinical accounts is clearly not incidental, given that studies suggest four times as many boys currently receive an ASD diagnosis as girls (Gillberg and Wing 1999).7 As we’ve seen, I’m especially interested in the minority, who, as we might well imagine, could struggle to obtain a diagnosis for and then cope with a predominantly male disorder. As with the emotional geographies of women’s health that I’ve done in the past, the work I propose to do on ASDs won’t intervene in on-going, important and often fascinating clinical debates about the disorders’, for example, etiology, incidence and prevalence. Social scientific perspectives are obviously different, but nonetheless valuable, and so far surprisingly scarce. Recent years have seen conceptualizations (and arguably experiences) of other disorders benefit from geographical interventions, including disability (Chouinard 1999), chronic illness (Moss 1999), mental ill-health (Parr 1999; 2000: Segrott and Doel 2005), eating disorders (Dias 2003) and other ‘a-typical’, often gendered and contested, embodied and emotional experiences (Bondi, Davidson and Smith 2005). (As we’ll see, many such disorders, including, for example, anorexia, 5 Joyce Davidson Draft only phobias and obsessive compulsive disorder, have in fact been among the misdiagnoses obtained by ASD women.) However, despite this increasing attention to socio-spatial aspects of embodied and affective disorder, ASDs themselves have been largely neglected by social scientists (but see Daley 2004; Gray 2001; 2002; 2003 on parents’ perspectives) and little is known about what it means and how it feels to experience and cope with ASDs beyond the immediate realm of affected individuals. I want to suggest that feminist geographers might inform and enhance understandings of enigmatic ASD experience of the world, offering theoretical as well as therapeutic insights that might benefit those directly involved, whether personally or professionally. Clinical and lay conceptions of autism and diagnostic criteria have, inevitably, changed over the years since Leo Kanner published the first account in 1943, closely followed by a similar study by Hans Asperger in 1944 – he described children who seemed as though they had just fallen from the sky - what remains relatively stable is the view that autism is part of a wide spectrum of disorders characterized by “impairments in social and communicative development, and by the presence of repetitive and routinised behaviours, in preference to imaginative and flexible patterns of behaviour and interests” (Charman 2002: 249). Autistic traits are often referred to in terms of the “triad of impairments” social, communicative and behavioural. Accounts suggest that the ASD child; spends more time with objects and physical systems than with people; communicates less than other children do; shows relatively little interest in what the social group is doing or being part of it; and has a strong preference for experiences that are controllable rather than unpredictable (Baron-Cohen 2000: 490). It won’t have escaped our notice that these traits and their discursive representations are culturally coded as masculine rather than feminine. In a fascinating and gendered twist on recent clinical approaches, director of the Cambridge, UK based Autism Research Centre, Simon Baron-Cohen, argues that autism can be understood in terms of ‘essential difference’ and is in fact an example of what he terms ‘the Extreme Male Brain’ (EMB). His populist book on the subject – it has glowing jacket reviews by the Washington and National Posts – is crying out for feminist critique, but time and space preclude…. 6 Joyce Davidson Draft only In considering, first, the social and communicative aspects of impairment that position ASD individuals in their own worlds, descriptive accounts emphasize an obvious inability to employ the usually intuitive language ‘of hand and eye’. Non-verbal behaviours – gestures, eye contact, ‘body language’ - communicate little if anything to the ASD individual, who often finds others’ ability to understand and respond to such ‘cues’ entirely mysterious. Any supplementary input to conversation beyond the strictly verbal and straightforward (non-metaphorical and preferably factual) - only serves to confuse, to obfuscate rather than enrich or clarify the respondent’s intentions. The literature suggests that factual information, and often in large quantities, can be taken on board at an intellectual level, imported wholesale into the ASD experiential island, but it rarely makes broader connective ‘sense’. Few ever learn to ‘intuit’ information from social cues independently, but rather learn to deduce information by entirely logical means. Autistic people do not usually, therefore ‘get’ small talk, and the inability to engage in ‘gossip’, constructed as central to the stereotypically feminine social identity, can present particular difficulties for women. While many can learn to ‘make the right sounds’, such that questions can be asked and apparently appropriate answers given, there are usually clear indications to the non-autistic person that information or understanding cannot be said to have been ‘shared’. The ASD individual remains alone in that a-socially separate sphere. To give an illustrative example, I’m going to draw here on the writings of probably the most famous autistic author, Temple Grandin – a high functioning and highly accomplished academic – who writes at length and often eloquently of her struggle to learn, cognitively, to ‘read’ and respond to others appropriately. As a child trying to figure out why she didn’t ‘fit in’, she was aware that “something was going on between the other kids, something swift, subtle, constantly changing – an exchange of meanings, a negotiation, a swiftness of understanding so remarkable that sometimes she wondered if they were all telepathic.” (Sacks 259) Grandin has famously described herself as feeling like ‘an anthropologist on Mars’ – Oliver Sacks used her phrase to title his popular book – as trying to ‘figure out the natives’ or ‘aping human behaviour’ with its seemingly 7 Joyce Davidson Draft only magical unspoken elements. Grandin thus doesn’t understand others, but she can partially compensate intellectually, by bringing “computational power to bear on matters that others understand with unthinking ease”. She has to “‘compute’ others’ intentions and states of mind, to try to make algorithmic, explicit, what for the rest of us is second nature.” (258) Donna Williams also, and fairly typically, uses technological metaphors to convey something of ASD women’s communicative coping techniques: “Like files in a computer, people can mentally store copied performances of emotions, retrieve them and act them out. But that doesn’t mean that performance is connected to a real feeling or that there is any understanding of a portrayed emotion beyond the pure mechanics of how and possibly when to emulate it” (Williams 1995: 214). Mind-reading and decoding the inner states of others is clearly extraordinarily hard work, and Grandin describes her still frequent feelings of being “excluded, and alien” (260). She can try to act, but never feels, or fits in, like a native. ‘Acting normal’ can thus be a purely imitative project, and authors refer to learning the art of mimicry in order to perform an(y) identity and survive the complexities of a necessarily social and unbearably demanding world: “I was an empty jar that could be filled with anything. People’s behaviour simply fell into the jar and I used it to try to feel myself someone, like a real person” (Gerland 2003: 209). The acts of imitation are, however, never managed entirely successfully and at no point is the project completed. While ASD individuals differ markedly from each other in their ability to accomplish and perform normality, none do so without enormous and exhausting effort, and few fail to be marked out as different and labeled accordingly, always detrimentally: “All the years of watching and studying what the normal people were about, I created my own piece of normality. In the eyes of my co-workers they thought of me as the crazy lady, bag lady or a drug user… Trying to be normal made me act like a nut…but at least [my co-workers] accepted me as some kind of person, even if some of them had me pegged as a big coke head.” (Lawson 2005: 29) Being anything or anyone is better than being nothing or nobody. 8 Joyce Davidson Draft only Enacting normalcy may present particular challenges to women with ASD - challenges more easily avoidable for men - given the gendered stereotypes and expectations around communicative styles. That is to say, women’s speech and body language is culturally constructed around co-operation and connection rather than competition and distinction, and doing gender appropriately for women arguably involves being more sociable, sympathetic and insightful. Obviously, ASD men also have difficulties with social relations and spaces where ‘mind-reading’ appears to take place. However, it is widely considered less permissible, more deviant, for women to perform inadequate interaction in social (skills-based) spheres. As Miller explains: “Consider how much of femininity is about taking a precise reading of all the social currents of a given moment and aligning (and if necessary, abnegating) oneself to serve the stability of the moment and the wellbeing of all those who inhabit it, whether this means sniffing out the exact social dress code… the subculture, and occasion, or reading all the social clues in a group and occupying the niche most guaranteed to soothe, nurture, and harmonize all who are in it. This is not the role our wiring has created for us” (Miller 2003: xii). The everyday ‘telepathy’ that takes place between typical individuals of both sexes is an inexplicable mystery to those with ASDs, and Jane Meyerding (in Miller 2003: 159) describes her own painful awareness of difference and disability at an early age. Those around her simply knew “how to be little girls together…as if everyone else had studied a script and learned their parts beforehand.” She was baffled by the “natural ease with which they acquired their gender identity from the culture around them” and feels that our culture makes it harder for girls and women to survive without such mysterious social skills than it is for boys and men. Such potentially significant experiential and cultural considerations have been absent from clinical accounts, which invariably model the ASD individual in gender ‘neutral’ (and so singularly male) terms. 9 Joyce Davidson Draft only In a well-documented clinical attempt to understand why such imitation and ‘active’ (rather than ‘natural’) learning should be necessary - to ‘unravel the mysteries of autism’ - Uta Frith and others have developed a theory of ‘central coherence’. This suggests that non-autistic people are able, arguably compelled, to draw diverse aspects of experience and situations together in a way that forms a coherent pattern. This ‘drive’ for central coherence entails a tendency to make things meaningful by integrating information into a larger system or context, such that deeper meaning can be derived from the gestures and expressions of others, when combined with what they simply ‘say’. In stark contrast, it is characteristic of ASD individuals, as we’ve seen, not to connect linguistic and supplementary information with a wider context, but to perceive it discreetly. This can apply at all levels, to all kinds of perceptions, and at all spatial scales, including the supposedly intimate human face, which can be perceived in discrete parts. If you can imagine the disturbing image or rather sense of disjointed mouth, nose and so on, this helps us understand why eye contact can be so frightening and impossible to maintain – faces have been described as “blurry objects exploding with invasive stimuli” (PrinceHughes 2004: 169). ASD individuals can be thought to look through other people, as if they weren’t there, and we might think that indeed those others don’t have any meaning in the autistic person’s world. Faces often make little ‘sense’, and if we consider the common shared space of communication and understanding with others that facial expressions often facilitate, we can perhaps get a sense of the extent of taken for granted shared space from which those with ASDs are excluded. Typical individuals rely heavily on such information in everyday life, and such perceptual difference can help ‘us’ (nonautists) understand behavioral patterns and difference, as well as atypical – ‘unfeminine’ - social, communicative experience. Because they are often more sensitive to sensory stimuli, the worlds of ASD individuals can be overwhelming - many notice everything, often in painful, indiscriminate detail – as one writer states, they might not be able to see the wood for the trees but they can see each tree in its minute and exquisite complexity. As a consequence of what’s described as a sensory onslaught, personal space can become over-populated with anxiety provoking stimuli that cannot be processed and properly placed, but cannot be blocked. Descriptions 10 Joyce Davidson Draft only include accounts of sensations heightened to an excruciating degree, and complete lack of modulation of senses, such that ears are helpless microphones, transmitting everything, irrespective of relevance, at full, overwhelming volume. Sight and smell too can clash to create a multi-sensually overwhelming attack on the self, and even the light wellintentioned touch of another can be unbearable. Prince-Hughes (2004: 67) writes that “I lived in a kaleidoscope […] looking down a narrow tunnel at broken colored fragments of people and dreams”. Williams offers a remarkably similar account of ASD tunnel-like experience in her book Nobody Nowhere (2002: 74): Explaining that ordinary physical environments could be felt to disappear, she writes that “perceptually, the hall did not exist. I saw shapes and colors as it whooshed by.” Perhaps surprisingly, given the central coherence account referred to above, both of these ASD authors describe a reliance on context for a sense of security amidst this spatial and sensual confusion. Prince-Hughes thinks she experiences attachment to places like others do with people and Grandin describes being upset when a favourite aunt died, but absolutely distraught when she found out “that her ranch was for sale. The idea of the loss of the place made me grief-stricken”. I think we can understand this attachment to place in terms of a desperate need for some sense making context of stability and predictability in a world peopled with never-ending, frightening surprises. PrinceHughes, for example, writes: “often I would not accept changes, and if we passed the site of a fallen tree or a new building I would close my eyes and remember it the way it was until we had moved on to the safety of the sacred permanent”. There are many similar examples of such passive, protective deployment of a geographical imagination; Grandin’s descriptions of her own internal “visual symbol world that allowed her to keep going” is incredibly illuminating. She imagines doors, gates, passageways as mental boundary markers that help her negotiate real barriers in the jungle of the real world beyond the symbolic. There are, however, many different ASD responses, where change is resisted far more forcefully. Fearing they’re losing their grip on the world, that it’s shifting and so wresting control from them, some others initiate a form of counter action, using some physical and / or psychical means to block the world out or stop it in its tracks - placing hands over ears and screaming at full volume isn’t unusual. Another autistic 11 Joyce Davidson Draft only writes that “nobody ever asked me why I stomped my feet, or screamed, or thrashed around with my arms. […] I just wanted everyone to shut up. It was overwhelming – horrible.” (Collins 102) In such a meltdown, self-injurious behavior can also be used to apparently cut through all other sensation and restore a sense of the familiar, redrawing a boundary on the body itself. Williams (2002: 215) explains that self-harm can also involve “testing as to whether one is actually real. As no one person is experienced directly, because all feeling gets held at some sort of mental checkpoint before being given to self by self, it is easy to wonder whether one in fact exists.” Those at the higher functioning end of the spectrum able to articulate such experience at least in written form, in their own space and at their own time, are perhaps able to learn the rules of appropriate behaviour and social and spatial tactics to help them cope with or contest change, in ways less disruptive, or obvious to ‘the natives’. Prince-Hughes (2004: 127) describes finding small spaces “where no change would occur”, shutting herself in this “small sanctuary” from the “sensory onslaught of the outside world” for literally hours at a time. Such “containment [she explains] silently reminded me of my physical boundaries – never solid and always in danger of disappearing.” With the outside world thus shut out, she thought often about death, hoping that heaven would be a place where nothing ever changed (Prince-Hughes 2004: 39). Given ASD worlds are so perceptually chaotic, it is surely unsurprising that individuals struggle to impose an order of sorts through resistance to environmental change, and repetitive and ritualized behaviour. Therese Joliffe writes from personal experience: “Reality to an autistic person is a confusing interacting mass of events, people, places, sounds and sights. There seem to be no clear boundaries, order or meaning to anything. A large part of my life is spent just trying to work out the pattern behind everything. Set routines, times, particular routes and rituals all help to get order into an unbearable chaotic life.” (76) ASD narratives such as this are reminiscent of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, recently examined from a geographical perspective by Segrott and Doel (2004) in an analysis that 12 Joyce Davidson Draft only demonstrates very powerfully that OCD sufferers constantly need to re-order space using an imaginative variety of tactics intended to protect psycho-social as well as physical boundaries. Order is obviously of crucial importance in the perceptual experience of ASD individuals, perhaps considered especially precious because it’s such a rarity in the ‘natural’, chaotic course of their lives. Gerland (2003: 53) explains: “I used to write labels for various things. I wanted everything to be orderly, clear and separate. This was not some way of keeping inner chaos under control, but an attempt to arrange the external world according to the same system as my inner world, a way of establishing a slightly better accord between me and everything else.” Order has to be cultivated and nourished, protected precisely because of its own perceived protective properties. In the words of Prince-Hughes (2004: 25): “Autistic people will instinctively reach for order and symmetry: they arrange the spoons on the table, they line up matchsticks or they rock back and forth, cutting a deluge of stimulation into smaller bits with the repetition of their bodies’ movements.” Many accounts describe rocking movements as deeply calming, suggesting the body itself can be used to soothe the effects of over stimulation through smooth, repetitive, predictable behaviors – this extends to the way it is clothed. Prince-Hughes would always, if possible, wear the same pair of favourite pants – she says, “I felt like I would disappear if I were not hemmed in by the familiar and unchanging” (p. 20)8 - and goes further in attempts to deploy clothing as protective armor against the world. Thus: “I wore leather jackets because their weight and thickness calmed me; dark glasses, sometimes even at night, because they cut out some of the stimulation to my nervous system; and heavy boots that made me feel secure and grounded as I clomped around in them [she says she might have looked tough but was …] withdrawn and armored primarily out of anxiety and confusion.” (p. 79) Such performances of emboldened boundaries present at least outward challenges to expectations around gendered norms, in contrast to the ‘internal’ state of affairs: ASD women in social space are more likely to feel introverted, insecure and otherwise more stereotypically feminine. I’ve been really struck in sartorial accounts such as that of Prince-Hughes by similarities with phobic coping mechanisms aimed at averting a perceived crisis in the integrity of weakened psycho-corporeal boundaries. There’s a world of difference in many ways between such 13 Joyce Davidson Draft only phobic anxiety disorders and affective disorders like ASDs, but perhaps the experiential similarities in terms of social and spatial coping mechanisms are worthy of further, geographical, investigation. So far, I’ve tried to demonstrate that ASD experience might be conceptualized and theorized spatially in a way that is sympathetic and respectful, as well as valuable. I’ve suggested there may well be some experiential linkages between ASD women’s ‘geographies of exclusion’ and previous work on emotional disorders that should be further explored, and would tentatively suggest that a study of the experience and production of space by and for people with ASD might also provide insights into the production of space in everyday, perhaps more typical and typically social life. However, I now want to move on to consider in more depth the nature and implications of gendered dynamics of diagnosis for ASD women, continuing to use their own words as far as possible. Diagnosis: Engendering Autism Awareness In Peter Szatmari’s A Mind Apart, he recounts the events following his receipt of a letter from Sharon, who articulates her reasons for writing in a way that is clear, insightful and moving: “Since I first heard of autism I have thought of it as ‘my problem,’ and this conviction only deepens as I learn more, and as I fail to change myself despite my best efforts. While professional diagnosis may be a comfort, professional denigration would be painful, which is why I have avoided exposing myself to anyone qualified to deny my self-diagnosis. The main reason for writing now is the hope of finding a support group of fellow adult recoverees. I would really like to find some company.” (in Szatmari 2004: 59/60) Szatmari describes his meetings with Sharon at some length, and also provides us with some detail regarding the complex nature of diagnosis from a clinician’s perspective. 14 Joyce Davidson Draft only Clearly, “there is no blood test or brain scan that will tell us who has ASD and who does not”, and with an adult patient such as Sharon, there are particular ‘challenges’ relating to the lack of corroborating evidence and the need to rely on the individual’s own account of their developmental history. The difficulties may thus be significant, and although Szatmari explains that “[w]hat she described to me was certainly analogous to the experiences of people with ASD”, “in the end” he decides that he could not, in fact, “give” her this diagnosis: “Sharon’s insights into her own predicament were just too good and her accomplishments too impressive” (Szatmari 2004: 77). The extent to which he claims to have learned about the nature of ASD from her experience is then puzzling, given that she does not (is not allowed to) own the identification. Nonetheless, Szatmari is clearly pleased to have gained such considerable insight from her contributions, and puts a self-satisfied end to the story by saying goodbye to his ‘sub-clinical’ patient and going to collect his mail, “in hopeful anticipation of other gifts that might come my way” (p.78). What Szatmari might give back, albeit unwittingly, is an increased awareness of the strategic (political and methodological) importance of prioritizing women’s own accounts and interpretations of their experiences over and above those that are clinically reductive and / or dismissive. This strategy includes taking seriously those diagnostic categories with which women choose to identify, the labels they elect to apply to themselves in preference to those many others they have often been stuck with. As Prince-Hughes (2002: xxii) points out “[m]any people with autism care little for the fine distinctions of category, preferring to focus on the common underpinnings of the phenomenon.” I intend to follow this lead and stay faithful to labels deemed significant by writers themselves. We have already noted that misdiagnoses among ASD women are common-place, and many of the alternative explanations and labels they collect are of a more stereotypically ‘appropriate’ and common feminine form. Michelle, for example, was cast as anorexic because of her troubled and apparently strange – but in fact typically autistic relationship with food.9 She had managed to ‘pass’ as relatively normal in relation to her own and others’ eating habits prior to leaving home to attend college. In this new and 15 Joyce Davidson Draft only overwhelming environment, she was expected to eat with other students in the very public cafeteria, a ‘nerve-wracking’ place that failed to facilitate the development of a protective, comforting routine – few other students would request and indeed require the exact same foods everyday. Michelle’s intolerance for disturbing colour and texture combinations severely restricted her options, and so she ate very little, with the following distressing results: “After a couple of weeks of telling me continuously that I wasn’t fat (which struck me as odd, as I never thought I was) pressuring me to eat more, and monitoring every bite I took, they finally ‘turned me in’ to the school counselor…. It was a matter of shape up, or ship out” (in Prince-Hughes 2002: 46). Michelle was in fact threatened with admission to a psychiatric ward, which, predictably, sent her anxiety “through the roof. I took to rolling up into a little ball and rocking under tables again, something I hadn’t done much since pre-school” (in Prince-Hughes 2002: 46). Though Michelle was eventually able to negotiate a compromise satisfactory to the ‘authorities’, the consequences for her own health were dire. Forcing herself to eat in public, but literally unable to stomach available food combinations, she began regurgitating her meals, and felt forced to do so for some time until she was able to create a more mutually acceptable routine. The compromise required displaying two kinds of food on a plate at the one time: Less than two was unacceptable to others, more than two was unmanageable for her, but so long as “they were the kinds of items that said, ‘We comprise a normal meal’ to everyone who looked” two items were satisfactory to all (in Prince-Hughes 2002: 48).10 As with other ASD women, Michelle had a great many unusual habits, but it was her disordered eating – more typical of women than men - that attracted the greatest attention and attempts at intervention and control. Other misdiagnoses – including forms of ‘severe and enduring’ mental ill-health - may be somewhat less stereotypically feminine in nature than anorexia or the chronic depression and anxiety so commonly encountered in diagnosis. However, the simple avoidance of ASD as a potential diagnostic outcome is in itself potentially significant for our gendered analysis. Misdiagnoses can be at least partially understood in terms of clinicians’ presuppositions about ‘male’ and ‘female’ problems: when disordered women come to 16 Joyce Davidson Draft only the attention of medical professionals, ASD will not be the first – and may not even be the last – of those labels that enter their minds. The results can be immensely disruptive to the course of a woman’s life. Patricia Clarke, for example, felt forced to adopt and adapt to the label ‘bipolar’, applied to her in her thirties. She took the prescribed medication for 13 years, “terrified that I would end up institutionalized for insanity, having no idea what was going on, or that my behaviour was actually normal for a person in my circumstances” (in Miller 2003: 82). Others undergo a series of more typical and less disturbing ‘diagnoses’ over many years before such disturbing labels were finally applied. At school, Lawson was “considered lazy, slow and immature for my age … I remember one teacher saying that I was ‘educationally subnormal’…. Other children called me ‘crazy’ or ‘mad’ and some didn’t like to play with me.”11 Gerland (2003: 80) suffered similar misunderstandings as a school child, and was described in the following terms: “Lazy. Doesn’t listen. Doesn’t help. Careless. Inattentive. Drags her feet. Hears only what she wants to hear. Sulks.” (She later adds “silly, willful, stubborn, rude, spoilt, and defiant” to the growing list.) Negative behavioural judgements and pseudo-diagnoses based particularly around perceived mental deficiencies are perhaps the most commonly applied to ASD children: “I was a nut, a retard, a spastic. I threw ‘mentals’ and couldn’t act normal” (Williams 2002: 11).12 Many of the common perceptions become increasingly harsh with the growth of the girl towards womanhood: “the older I grew the more was demanded of me, while at the same time I had increasingly less access to any childish charm that might have compensated for my failings. A withdrawn chubby four year old could be met with a little more indulgence from the world around her than a suspicious and overweight ten year old” (Gerland 2003: 122). The labeling process often becomes increasingly explicitly feminized: “To some people my attitude either came off as being a bitch or mad” (Cowhey 2005: 21); “I was also thought of as being a witch” (Cowhey 2005:127).13 17 Joyce Davidson Draft only Following Lawson’s troubling girlhood, she left school and experienced increasing difficulty in the ‘outside’ world. She ‘crashed’ and entered an institution. Although Lawson doesn’t remember the events leading up to her admission at all clearly, “[t]he doctors saw my agitation and constant mobility as undesirable and prescribed Largactil to calm me down. [After a few months…] my very lifeblood felt sucked dry and I had no desire to relate to anyone or anything” (Lawson 2005: 67). She attempted suicide at age 20 and entered the institution for a second time, considered to be having ‘another schizophrenic episode’. She describes the place as deeply depressing, feels lucky to avoided ECT and resolved never to return to the hospital again, deciding that “[i]f they think I am mad, then I must prove them wrong” (Lawson 2005: 77).14 For Lawson, it was 25 years before the diagnosis of schizophrenia was overturned. “I was diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome after spending time with a psychologist at a wellknown Melbourne University in August 1994. It was a relief to be told I was not schizophrenic – but also scary to realize I had some other ailment that had no cure” (Lawson 2005: 77). She then worked hard to educate herself about her new disorder: “My hunger for information and understanding pursued me like a lost dog. The more I read about depression and schizophrenia, the more I was convinced these conditions did not belong to me” (p. 92). Williams too describes searching for insight in the medical section of her local library: “I buried my head in books on schizophrenia and searched desperately to find a sense of belonging within those pages that would give me a word to put to all of this. / Suddenly it jumped out at me from the page… ‘Autism’, it read, ‘not to be confused with schizophrenia’.”15 Following further research, “I felt both angered and found. The echoed speech, the inability to be touched, the walking on tiptoe, the painfulness of sounds, the spinning and jumping, the rocking and repetition mocked my whole life.” She was twenty six years old, and had no satisfactory sense of self understanding, having felt forced to accept the probable accuracy of others’ words for such a significant part of her life: “Until I had actually met someone who was like me, I hadn’t realized that my ‘quirks’ and ‘difficulties’ were anything other than my mad, bad, or sad personality” (Williams 1995: 80). Although she is reassured by the discovery of autism, it is not a label welcomed by all those who knew her, and her problems have been 18 Joyce Davidson Draft only altered rather than resolved.16 For many others, the perceived accuracy of the new label at least provides some comfort and potential access to a community of others: “At the time that we as autistic people finally get a diagnosis – especially if that diagnosis occurs in adulthood – we are relieved just to know there are others like us out there.” Prince-Hughes is among those for whom obtaining a diagnosis served as an enormous relief, helping her to finally make some sense of her unusual life. At the age of thirty six, she felt able, at long last, to take some control over her circumstances, and such relatively simple steps as changing her diet and taking medication to help with compulsive symptoms, improved her quality of life almost immediately.17 Despite the sense that such changes could have been made much earlier had an appropriate diagnosis been forthcoming, she and other ASD women are largely sympathetic to the challenges clinicians face when presented with their complex and changing, oddly contextdependent symptoms. Often, these are further complicated when presented through the prism of wildly differing quirks, characteristics, and ‘eccentric’ personalities. Miller (2003: xix), for example, recognizes that: “the diagnostic difficulty is rooted in the diversity of autism itself, which is neither unitary, nor binary, but plural [and is further complicated by the] likelihood of comorbidity. Many autism spectrum people have one or more other conditions, such as Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD), chronic or recurrent mood disorders, Tourette’s Syndrome traits, learning disabilities, Prosopagnosia [inability to read faces] and others.” Accordingly, whichever symptom the person presents most prominently, whether intentionally or not, tends to become the primary diagnosis. Further barriers to diagnosis face those who are high functioning - for example, maintaining jobs and relationships “or otherwise not needing, or at least not getting social or medical intervention”. The DSM-IV checklist “imposes the criterion of significant impairment in critical areas of the person’s life. A number of people have been refused diagnosis on this basis” (as with Szatmari’s patient Sharon, who simply ‘had too much insight’ to be on the autism spectrum). The extent of the effort that ASD women have made to survive despite their profound difficulties can then serve to significantly 19 Joyce Davidson Draft only undermine their efforts to obtain an accurate diagnosis. As Angie explains - not unsympathetically - “I know it is hard to diagnose in adulthood because we can learn to compensate and cover” (in Prince-Hughes 2002: 77). Similarly, Miller (2003: xxii) states: “[m]ost high-functioning autistic people, not knowing what is ‘wrong’ with them, develop a lifetime pattern of using their intelligence to find ways to appear normal. … Like others who seek to be what they are not, we invariably end up with painful memories at best and self-loathing at worst.” Aside from the harmful implications for ASD women themselves, failure among clinicians to recognize the significance of women’s attempts at passing strange to be ‘normal’ means they continue to operate with and perpetuate an inaccurate picture of autism across its spectrum of affects. This is a picture from which women remain conspicuously absent, and efficacy of ASD theories and treatments suffer significantly as a result.18 Final Section and Conclusions…. There are a number of interconnected aspects that need to be further developed / teased apart: 1. Clinicians are less aware of the existence of ASDs in women and thus less likely to ‘see’ and then diagnose it. 2. ASDs may be manifested and experienced differently by girls and women, as evidenced by the following quotes: “In recent years, the growing number of women seeking diagnosis has called into question not only the condition’s prevalence in the female population, but its commonly accepted parameters as well. Professionals are beginning to speculate that AS often manifests differently in women… [girls may] have the same passion for facts but less drive to exhibit that knowledge. Clinicians who default to this boyish profile engendered by their own diagnostic narrowness may have a blind spot that keeps them from seeing the whole autistic spectrum. At the same time, little professorial girls may be seen as a social anomaly (not acting like girls), and their perceived socio-sexual deviance may obscure their neurological difference” (Miller 2003: xxi). 20 Joyce Davidson Draft only “AS is often diagnosed in response to a series of events originating in a school teacher’s observation of aberrant behavior. A child who is aggressive, noisy, exhibiting lack of motor inhibition (wild, acting out) is attended to, and this behavior is characteristic of boys. A child who is well behaved, quiet, and apparently compliant will often be overlooked, sometimes despite underachievement. Such a child is quite likely to be a girl” (Miller 2003: xxi). 3. Some of the acceptable roles open to women provide a cover for ASD traits, contributing further to their diagnostic marginalization. Entering into a partnership with a man can be a ‘survival decision’, giving the appearance of normality, as well as support, someone to copy and help navigate the world. (ASD women can and many do ‘choose’ to lead very private lives, based around home and family. Fulfilling a socially acceptable and even valued social role serves to deflect unwanted attention) 4. BUT, women are also expected to have social skills and display empathy in a way that men are not, meaning that ASD women may be labeled as ‘cold’, standoffish, snobbish, unfriendly, a ‘bitch’ and so on. Women lacking social skills may be criticized and devalued more than similarly incompetent men. 5. ASD women can and do experience and perform different versions of gender, and contest expectations of others in socially significant ways. “having autism underpinned much of my gender identity or rather lack thereof. I have since learned that most autistic people do not see gender as an internal or external category that is important or even applicable, especially to themselves”. (Prince-Hughes 2004: 59) “I never learned to see my body as a woman’s body in the sense that a woman’s body is an actor in socio-sexual relations. My body is the support structure for me, my intellect, my memories, my sensory experiences. If it has a gender, that gender lives on the outside, not in here where it would make a difference to how I feel or see the world (except in so far as I am shaped by how my gender causes the world to see and feel about me).” (Meyerding, in Miller 2003: 165/6) “I was an androgynous kid and most clearly perceive the world in a non-gendered way” (Jean, 38) 21 Joyce Davidson Draft only Conclusions need to think seriously about the multiple implications of gender for the experience of ASD women, in terms of approaches to diagnosis and development of coping mechanisms / educational interventions sensitive and appropriate to ‘other’ gendered experience. References Alvarez, Anne and Reid, Susan (1999) Autism and Personality: Findings from the Tavistock Autism Workshop London and New York: Routledge. American Psychiatric Association. (2000) DSM IV: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., Text Revision), Washington, DC: Author. Anderson, Kay, and Susan Smith (2001) Editorial: emotional geographies, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 26: 7-10. Bailey, Cathy, Catherine White and Rachel Pain (1999) ‘Evaluating Qualitative Research: Dealing with the Tension Between ‘Science’ and ‘Creativity’’, Area 31, 2, 169-183. Bankey, Ruth (2002) Embodying agoraphobia: rethinking geographies of women’s fear, in Liz Bondi, Hannah Avis, Amanda Bingley, Joyce Davidson, Rosaleen Duffy, Victoria Ingrid Einagel, Anja-Maaike Green, Lynda Johnston, Sue Lilley, Carina Listerborn, Mona Marshy, Shonagh McEwan, Niamh O’Connor, Gillian Rose, Bella Vivat, and Nichola Wood, Subjectivities, Knowledges, and Feminist Geographies Lanham MD: Rowman and Littlefield, pp. 44–56. Baron-Cohen, Simon (2000) Is Asperger syndrome / high-functioning autism necessarily a disability? Development and Psychopathology 12: 489 – 500. Baron-Cohen, Simon (2003) The Essential Difference: Male and Female Brains and the Truth About Autsim. Basic Books: New York. Blakemore-Brown, Lisa (2002) Reweaving the Autistic Tapestry. Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London and Philadelphia. Bondi, Liz, Davidson, Joyce, and Smith, Mick (2005) ‘Introduction: Geography’s Emotional Turn’, in Davidson, Joyce, Bondi, Liz and Smith, Mick (Eds.) Emotional Geographies (Burlington VT and Aldershot: Ashgate Press). Britten, Nicky (2000) ‘Qualitative Interviews in Health Care Research’, in Pope and Mays. Bruey, Carolyn Thorwarth (2004) Demystifying Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Guide to Diagnosis for Parents and Professionals. Woodbine House: Bethesda, MD. Capps, Lisa and Sigman, Lisa (1996) ‘Autistic Aloneness’, in Kavanaugh, Robert D., Zimmersely, Betty and Fein, Steven (eds.) Emotion: Interdisciplinary Perspectives (Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence Embaum Associates Inc.). Charman, Tony (2002) The prevalence of autism spectrum disorders: recent evidence and future challenges, European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 11: 249 – 256. Chouinard, Vera (1999) Life at the margins: disabled women’s explorations of ableist spaces, in Elizabeth K. Teather (ed) Embodied Geographies: Spaces, Bodies and Rites of Passage. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 142-156. 22 Joyce Davidson Draft only Clarke, D. and Fairburn, C. G. (1997) Science and Practice of Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Cohen, Judith H. (2005) Succeeding with Autism: Hear My Voice. Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London and Philadelphia. Cowhey, Sharon P. (2005) Going Through the Motions: Coping with Autism. Publish America: Baltimore. Daley, Tamara C. (2004) From symptom recognition to diagnosis: Children with autism in urban India, Social Science and Medicine 58: 1323 – 1335. Davidson, Joyce (2000) ‘A phenomenology of fear: Merleau-Ponty and agoraphobic lifeworlds’, Sociology of Health and Illness, 22, 5, 640-660. Davidson, Joyce (2001) “‘Joking Apart….’: A ‘Processual’ Approach to Researching Self-help Groups.” Social and Cultural Geography, 2, 2, 163-183. Davidson, J. (2002) ‘All in the Mind?’ Women, Agoraphobia and the Subject of SelfHelp. In, Bondi, L. (ed.) Subjectivities, Knowledges and Feminist Geographies, Colorado: Rowman and Littlefield. Davidson, Joyce (2003a) Phobic Geographies: The Phenomenology and Spatiality of Identity (Burlington VT and Aldershot: Ashgate Press). Davidson, Joyce (2003c) ‘‘Putting on a face’: Sartre, Goffman and Agoraphobic Anxiety in Social Space’, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 21, 1, 107 - 122. Davidson, Joyce (2005) ‘In a world of his own…’: An emotional geography of autism, paper presented to the annual meeting of the Association of American Geographers, Denver, Co., April 5-9. Davidson, Joyce (2005) ‘What’s Funny About Phobias?’ Mental Health Today, April, 2224. Davidson, Joyce (2005) ‘Contesting Stigma and Contested Emotions: Personal Experience and Public Perception of Specific Phobias’, Social Science and Medicine. Davidson, Joyce and Milligan, Christine (2004) ‘Embodying Emotion, Sensing Space: Introducing Emotional Geographies’, Social and Cultural Geography, 5, 4, 523 – 532. Davidson, Joyce and Smith, Mick (2003) ‘Bio-phobias / Techno-philias: Virtual Reality Exposure as Treatment for Phobias of ‘Nature’’, Sociology of Health and Illness, 25, 6, 644 – 661. Davidson, Joyce, Bondi, Liz and Smith, Mick (Eds.) (2005) Emotional Geographies (Burlington VT and Aldershot: Ashgate Press). Dias, Karen (2003) The Ana Sanctuary: Women’s Pro-Anorexia Narratives in Cyberspace, Journal of International Women’s Studies, 4: 2, http://bridgew.edu/SoAS/jiws/April03/index.htm Durig, Alexander (1996) Autism and the Crisis of Meaning. SUNY: New York. Fairclough, Norman. (1992) Discourse and Social Change (Cambridge: Polity Press). Fombonne, Eric (1999) ‘The Epidemiology of Autism: A Review’, Psychological Medicine 29: 769 – 786. Gerlai, Julia and Gerlai, Robert (2003) ‘Autism: A Large Unmet Medical Need and a Complex Research Problem’, Physiology and Behaviour 79: 461 – 470. Gerland, Gunilla (2003) A Real Person: Life on the Outside. Souvenir Press: London. 23 Joyce Davidson Draft only Gillberg, C. and Wing, L. (1999) Autism: Not an extremely rare disorder, Acta Psychiatrica Scandanavia 99: 399 – 406. Grandin, Temple (1996) Thinking in Pictures: And Other Reports From My Life With Autism. New York: Vintage Books. Grandin, Temple and Scariano, Margaret M. (1996) Emergence Labelled Autistic. Warner Books: New York. Gray, D. E. (1994) Coping with autism: stresses and strategies, Sociology of Health and Illness 16 (3): 275 – 300. Gray, David E. (2001) Accommodation, resistance and transcendence: three narratives of autism, Social Science and Medicine 53: 1247 – 1257. Gray, David E. (2002) ‘Everybody just freezes. Everybody is just so embarrassed’: felt and enacted stigma among parents of children with high-functioning autism, Sociology of Health and Illness 24 (6): 734 – 749. Gray, David E. (2003) Gender and coping: the parents of children with high functioning autism, Social Science and Medicine 56: 631 – 642. Haddon, Mark (2004) The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time. Anchor Canada. Houston, Rab and Frith, Uta (2000) Autism in History. Blackwell Publishers: Oxford. Lajoie, M. (1996) Psychoanalysis and Cyberspace. In Shields, R. (ed) Cultures of Internet: Virtual Spaces, Real Histories, Living Bodies. London: Sage, 153-69. Lawson, Wendy (2005) Life Behind Glass: A Personal Account of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London and Philadelphia. Lupton, Deborah. (1994) Medicine as Culture: Illness, Disease and the Body in Western Societies (London: Sage). Miller, Jean Kearns (2003) Women From Another Planet: Our Lives in the Universe of Autism. Dancing Minds: Bloomington, IN. Moore, D. and Taylor, J. (2000) Interactive Multimedia Systems for Students with Autism, Journal of Educational Media, 25, 169-177. Morse, J. M. (1992) Qualitative Health Research. London: Sage. Moss, Pamela (1999) Autobiographical notes on chronic illness, in Ruth Butler and Hester Parr (eds) Mind and Body Spaces: Geographies of Illness, Impairment and Disability. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 155-166. Nash, M. J. (2002) The secrets of autism: the number of children diagnosed with autism and Asperger’s in the US is exploding. Why? Time 159: 47 – 56. Park, Clara Claiborne (2001) Exiting Nirvana: A Daughter’s Life with Autism. Little, Brown: Boston, New York and London. Parr, Hester (1998) ‘The politics of methodology in ‘post-medical geography’: mental health research and the interview’, Health and Place Parr, Hester (1999) Delusional geographies: the experiential worlds of people during madness and illness, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 17: 673-690 Parr, Hester (2000) ‘Interpreting the Hidden Social Geographies of Mental Health: Ethnographies of Inclusion and Exclusion in Semi-Institutional Places’, Health and Place, 6, 225-237. Parsons, Sarah, and Mitchell, Peter (2002) ‘The Potential of Virtual Reality in Social Skills Tarining for People with Autistic Spectrum Disorders’, Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, Vol. 46, Part 5, pp. 430-443. 24 Joyce Davidson Draft only Parsons, Sarah, Mitchell, Peter and Leonard, Anne (2004) The use and understanding of virtual environments by adolescents with Autistic Spectrum Disorders, in Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, Vol. 34, No. 4, pp. 449-466. Pope, C., Ziebland, S. and Mays, N. (2000) Analysing qualitative data. In Pope, C. and Mays, N. (eds.) Qualitative Research in Health Care. London: BMJ. Pope, Catherine and Mays, Nicholas (eds.) (1999) Qualitative Research in Health Care (London: BMJ). Prince-Hughes, Dawn (ed.) (2002) Aquamarine blue 5: Personal Stories of College Students with Autism. Swallow Press: Athens, Ohio. Prince-Hughes, Dawn (2004) Songs of the Gorilla Nation: My Journey Through Autism. New York: Harmony Books. Quill, K. A. (2000) Do-Watch-Listen-Say: Social and Communication Intervention for Children with Autism. Baltimore: Brooks. Riva, Giuseppe (2003) Virtual Environments in Clinical Psychology, Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, Vol. 40, No. 1/2, pp. 68-76. Sacks, Oliver (1995) An Anthropologist on Mars. Picador: London. Seltzer, M. M., Krauss, M. W., Shattuck, P. T., Orsmond, G., Swe, A. and Lord, C. (2003) The symptoms of autism spectrum disorders in adolescence and adulthood, Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 33 (6): 565 – 581. Smith, Mick and Davidson, Joyce (in press) “It makes my skin crawl….” The Embodiment of Disgust in Phobias of ‘Nature’, Body and Society, 12: 1. Szatmari, Peter (2004) A Mind Apart: Understanding Children with Autism and Asperger Syndrome. The Guilford Press: New York and London. Weiss, M. J. and Harris, S. L. (2001) Reaching Out, Joining In: Teaching Social Skills to Young Children with Autism. Bethesda, MD: Woodbine House. Wilensky, Amy (1999) Passing for Normal: A Memoir of Compulsion, New York: Broadway Books. Williams, Donna (1992) Nobody Nowhere: The Extraordinary Autobiography of an Autistic (New York: Random House). Williams, Donna (1994) Somebody Somewhere: Breaking Free from the World of Autism (New York: Random House). Williams, Donna (2003) Exposure Anxiety, The Invisible Cage: An Exploration of SelfProtection Responses in the Autism Spectrum and Beyond. Jessica Kingsley Publsihers: London and New York. Williams, Donna (2004) Everyday Heaven: Journeys Beyond the Stereotypes of Autism. Jessica Kingsley Publsihers: London and New York. Wing, Lorna (1997a) Syndromes of autism and atypical development, in Cohen, D. J. and Volkmar, F. R. (eds) Handbook of Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorders. New York: Wiley, pp. 148 – 170. The title is taken from a biographical note in Donna William’s (2004) Everyday Heaven: Beyond the Stereotypes of Autism: “She grew up with more labels than a jam jar and like many people with autism born in the 60s and earlier, she was not formally diagnosed with autism until adulthood.” 2 The paper that follows is very much a draft version in its early stages; the argument is in many places underdeveloped and incomplete, and the majority of the footnotes contain ‘extras’ and personal reminders. 1 25 Joyce Davidson Draft only I’m hesitant about using a term that attributes agency and active involvement to the women who contribute to this research – I’ve never spoken to them, they have signed no consent form. However, I think ethical appropriation of their (albeit published and publicly available) words demands some recognition of the extent to which their experience and ideas have shaped my own. They have thus participated significantly in the production of this paper. 4 This, in fact, was the case even with her own family, about whom she explains: “We scarcely came from the same planet” (Gerland 2003: 13). 5 There are many other similarly persuasive accounts. For example: “I could write essays all day – they do not bite back at me. The written word has a form all its own. The pen between my fingers feels solid and tangible. It moves with me and allows the symbols of my pain or ecstasy to reveal themselves. Words express my distress through the pen and onto the paper and back into my mind. I can see them on the paper; they talk to me and help me make sense of my life.” (Lawson 2005: 97) “I find the written word much easier to comprehend than the spoken word. It takes me a lot longer to process conversation and work out the meaning behind the words than it does to scan the words on a written page.” (Lawson 2005: 9) 6 I am no sense an insider in relation to ASD experience - my own sense of ‘alienation’ in a masculinist, marginalizing / medicalizing environment is on another plane entirely. 7 Though as we might expect, ASD women have used the same phrase in relation to themselves. For example: “To my family, I was always different because I lived in a world of my own.” (Lawson 2005: 12) 8 “I also liked being in small cramped spaces where it was quiet and calm, especially when I fitted exactly into the space. I wanted to put on a space, put on a sort of cave, like a garment.” (Gerland 24) 9 Susan, for example, “made the same thing for dinner for two years (club sandwiches with French fries and a pickle pear)”, eaten while listening to the same music. Gunilla Gerland (104) was frequently told that “‘food doesn’t bite you’, they said, laughing. But what did they now about it?” Describing fairly typical difficulties with food, she describes how she blends foods together to cope with different textures, causing a friend to say “you’re not pregnant or something are you?” My mind wondered what the ‘or something’ meant.” Lawson 9 10 The requirement to keep up appearances still exists for her, and she continues to make “attempts at normalcy – I keep a wide enough variety of foods stocked in my kitchen so that it looks normal [but..] there are probably less than 20 foods I eat at home on a regular basis. And even now, I tend to revert to my ‘one food only’ routine when I’m especially stressed or anxious.” 48 11 “For so many years, my disability was never acknowledged in my family. It was just a case of an unappreciative daughter / sister who liked to ‘do her own thing’. Once, during a conversation, my mother said to me, ‘you were never normal, you probably got it from your father’s side.’ / Got what, I wondered?” 13 12 “Sometime during the third grade, the realization that I was different began to grow. .. why were things that seemed so easy for other people so difficult for me? Was I perhaps backward? … Why wasn’t I a real person? / I sank into a sense of pointless ness, began comfort eating and grew fat. Now at least I had an externally tangible feature to be teased about.” 116 13 Cowhey states that “My life would not have been so confusing if I was diagnosed at a younger age. [However] I do believe forty-six years ago [that] probably would not have been much help, because that many years ago they would probably have put me in a nut house!” 160 “A crazy person is a good example of how most describe me [“Her elevator doesn’t reach the top floor!” 105] …. Autism has given me an odd and weird personality, but I’m not crazy, I’m different…being accepted in the normal world is hard and frustrating for me.” 67 14 ASD behaviour can look like “inattention, apathy, boredom, or worse: drug abuse, a rebellious nature, or perhaps a dangerous mental illness” xvii 15 Similarly, Gerland systematically went through books on psychology, medicine and psychiatry, trying to find out what might be wrong with her. When she picks up a book about autism by chance, “suddenly I had turned the right page in the right book. I recognized myself.” 234 “There was far too much of me described for it to be sheer chance.” “Now I was hunting for someone who might help me understand... and at last I had come to a place where I was taken seriously and where they knew a lot about my kind of difficulties. 16 “In the part-time job I had at my father’s workplace, I had been called a ‘smart kind of crazy-backward’. I explained to one of the people there about autism… I had made my father ashamed by their knowing I was autistic. / I don’t get it. Why would he be happier that people thought of me as crazy or backward but 3 26 Joyce Davidson Draft only ashamed that they knew I was autistic (which means that I am not very crazy at all, intelligent in many ways, and not necessarily mentally retarded)” 17 She was determined her partner should know that she doesn’t intend to live as a diagnostic description. Rather, she intends to put her research into autism to constructive use. Prince-Hughes keeps a journal to record and help her understand patterns in her behaviour and allows herself to use some of the more innocuous comfort rituals. In addition, she joins an online discussion group for adults on the autism spectrum who have been to university, all of which are experienced beneficially, and given her a sense of partial control over her life and disorder. (176) 18 As Miller contemplates: “I wonder how completely professionals can understand AS [used here to refer to both “Autism Spectrum and Aspergers Syndrome] without the bigger picture of those who live with AS everyday but have not seen fit to show up at their doors.” There is thus recognition among the women who record their experiences that there are aspects of autism that never reach clinicians’ radar: “AS is a neurological difference that often turns clinical in a culture that doesn’t value AS strengths. Much of our survival requires us … to become better functioning according to the cultural hegemony of NTs, the neurotypicals, who call the shots about what is valued in people.” Xix 27