Abstract:

advertisement

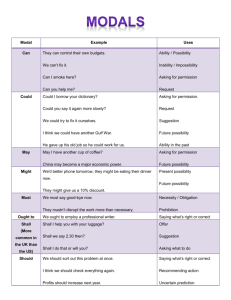

Asking and Giving Permission 1 Running head: ASKING AND GIVING PERMISSION Asking and Giving Permission In Vietnamese and English: A Contrastive Analysis Le Thi Thu Le University of Education Contrastive Analysis Mr Nguyen Ngoc Vu December 30, 2010 Asking and Giving Permission 2 Asking And Giving Permission In Vietnamese And English: A Contrastive Analysis No one can deny the fact that cultural values have a strong influence on the use of language, especially speech acts. Many researchers have conducted the studies of the contrastive analysis of speech acts between learners’ native language and the target language for the purpose of helping learners improve their communicative competence. In my essay, I have the attention of doing a research on the speech act of permission in Vietnamese and English because the speech act of permission is widely used in everyday interactions and plays a major role in communication. Specifically, I focus on the way to ask for permission and some expressions of giving permission to point out similarities and differences in terms of syntactic and semantic formulas between Vietnamese and English. In Vanderveken ‘s view, “By uttering sentences in the contexts of use of natural languages, speakers attempt to perform illocutionary acts such as statements, questions, declarations, requests, promises, apologies, orders offers and refusals.” (Vanderveken, 1990, p. 7). They are called speech acts. It may not be an exaggeration to say that mastering the use of speech acts is essential and practical. More importantly, the cross- culture study of speech acts needs to be invested because “the cross-culture study of speech acts is vital to understanding of international communication” (Eisenstein, 1989, p. 199) and Rosaldo also cautions that “Violations of cultural norms of appropriateness in interactions between native and nonnative Asking and Giving Permission 3 speakers often lead to sociopragmatic failure, breakdowns in communication and the stereotyping of nonnative speakers.” (Rosaldo, as cited in Hinkel, Long, & Richards, 2006). That’s why permission which is one of the commonly used speech acts should be considered in all respects. According to Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary (2000), the noun “permission” has two meanings. It is defined as the act of allowing somebody to do something, especially when this is done by somebody in a position of authority. Besides, another meaning of permission is an official written statement allowing somebody to do something. In my essay, I just focus on the first meaning to discuss permission speech act which makes up a high proportion in every interaction. So, asking for permission is the act of wanting to know whether a person can do something or use something or not. Ex: Can I use your bike? In Vietnamese dictionary (2010), the definition of asking for permission (xin phép) is quite similar to English definition. It is also used to make sure that a person is allowed to do something. Ex: Tôi có thể sử dụng máy tính của bạn được không? In daily life, whenever a person wants to do something or uses something that belongs to another person, it’s important to ask for permission. It is because asking for permission shows his/ her respect for others and increases the chances that his/her request will be granted. However, the expressions of asking for permission are differently expressed by different people in different cultures. The speech acts of asking for permission is indeed confusing and complicated. Therefore, the addressers should Asking and Giving Permission 4 pay much attention to the asking for permission expressions so as to make a polite permission that will be granted by the authority and avoid creating a permission which will be assumed as joking, rudeness or sarcasm. Also, utterances used to give permission should be deeply concerned in order to know the intentions which the addresser actually wants to say or to do. These intentions are revealed in the asking for permission expressions. In the previous studies, researchers take asking for permission into consideration. They investigated some unique factors involving in the way to ask for permission from others. They are: ethnic difference, gender difference, situation difference or social status difference. There is no doubt at all that “The way people ask for permission, to greater extent, is affected by the situation in which asking for permission is expressed different cultural background of the speakers.” (Soehartono & Sianne, 2003). In other words, cultural values or norms of behavior are likely to be responsible for producing different ways of asking for permission. After investigating the utterances expressed by the Chinese and Javanese students of SMU Krisyen petra 3 in asking for permission for taking leave, Soehartono & Sianne explain that ”Each ethnic has different opinion about what politeness is “(Soehartono & Sianne, 2003). Actually, according to Samovar and Porter, the notion that is deeply rooted in the English speaking culture is individualism (2000, p.67). One of the characteristic of individualism is that people in English speaking culture, especially the American believed all people have personal privacy. For instance, anybody mustn’t step into another’s house without permission. Nobody has the right to read any other’s letter even Asking and Giving Permission 5 parents mustn’t read their children’s private letters. That is the reason why people should ask for permission regardless of age, social status and relationship. People will be punished if they infringe upon any other’s personal privacy with the motivation of curiosity, profit or malice. It is because personal privacy is respected highly and protected by law in these countries. Similarity, the Vietnamese also highly regard asking for permission. In the past, Vietnamese ancestors create many valuable folk – songs, proverbs in order to teach posterity how to behave well, establish and maintain social rapports. For example: “Học ăn, học nói, học gói, học mở” Another proverb: “Đi thưa về trình” Moreover, Huynh explains that: In Vietnamese society, the predominant sentiment in the relation between members of a social group is respect. This is particularly evident in the attitude towards older people. Respect and consideration for old age no doubt derive from the obligation of filial piety that requires young people to respect and love their parents and parent-like members of the family. (Huynh, n.d.). Therefore, no one can deny the fact that people have to ask for permission to get married, stay overnight at the friend’s house, ect even though they are old enough to make decisions. Vietnamese people believe that if young people disobey the elders ‘advice, they will suffer bad consequences of their actions “Cá không ăn muối cá ươn Con cãi cha mẹ trăm đường con hư” Asking and Giving Permission 6 The elders are actually the carriers of the tradition and the embodiment of knowledge and wisdom. (Huynh, n.d.). In general, asking for permission in Vietnam and English speaking countries play the important role in every speech situation irrespective of culture. Regarding the frequency number of language functions, Soehartono & Sianne show that “There are four language functions that never occur in the permission utterances expressed to the teacher as the superior” (Soehartono & Sianne, 2003). They are: (1): Suggesting a course of action (2): Requesting others to do something (3): Advising others to do something (4): Instructing / directing others to do something By having analyzed the data, Soehartono & Sianne find out the predominant function seeking permission and conclude that: “Seeking permission function is followed by apologizing function that uses to show that they are in the lower position and reporting function that is used to convince the authority.” (Soehartono & Sianne, 2003). When it comes to this essay, its purpose is to systematically examine Vietnamese and English asking and giving permission to draw out some similarities and differences in terms of syntactic and semantic formulas and meet the requirements of language teaching and learning. In English language, the most familiar syntactic patterns are (1) Can I borrow your pen? Could he use your phone charger? Asking and Giving Permission 7 (Question head + S + Verb phrase with bare infinitive?) (2) Would it be OK if I borrow/ borrowed your pen? Would it be alright if he uses/ used your phone charger? (Question head + S + Verb phrase with simple present or past subjunctive?) (3) Do you mind if I borrow/ borrowed your pen? Would you mind if she uses/ used your phone charger? (Question head + S + Verb phrase with simple present or past subjunctive?) Meanwhile, syntactic formulas employed to ask for permission in Vietnamese language is quite limited. The most commonly occurring patterns are: (1) Tớ dùng điện thoại cậu nhé? (Can I use your cellphone?) (2) Em ngồi đây được không chị? (Would it be ok if I sit here?) (3) Con có thể đi chơi với bạn một chút được không mẹ? Con sẽ về liền. (May I go out with my friend for a while, Mom? I promise to come back home soon.) In Vietnamese language, there is a low frequency of the structures containing “if”. Even they are never employed. For Vietnamese people, the most commonly used syntactic patterns in English “Would it be ok if I borrow your pen?” or “Do you mind if I use your phone charger?” are the unusual patterns for the speech act of asking for permission. It is because that we can not translate two above utterances into Vietnamese “Would it be ok if I borrow your pen?” Asking and Giving Permission 8 ( Có được không nếu mình sử dụng bút máy của bạn?) “Do you mind if I use your phone charger?” (Bạn có phiền không nếu mình sử dụng cục sạc điện thoại của bạn?) It sounds unnatural and clumsy. That’s the reason why Vietnamese people seldom use these utterances to communicate. Instead, they have a tendency to say: “Mình mượn bút máy của bạn được chứ?” “Mình sử dụng cục sạc điện thoại của bạn được không bạn? When using these expressions to ask permission, Vietnamese people never forget to smile. It seems that they want to create intimacy and friendliness. Thanks to that, they can erase the strangeness and increase the possibility of granting. In term of semantic formulas, almost all the English expressions of asking permission contain modal verbs: can, could, may, might,…However, the choice of the appropriate modal verbs depends on age, social status, degree of acquaintance, respect, situation, ect. Ex- In the shop: a conversation between clerk and customer Clerk: May I help you? ( Tôi có thể giúp gì cho bạn?) - At school: a conversation between two friends (they have close friendship) P1: Can I use your pen? (Tớ dùng viết của cậu được không?) P2: Of course. (được mà) Moreover, when asking for permission to do something, the English usually use the word “please” to make the request sound more polite. It's not grammatically necessary to use “please” but a person may sound rude if he/she doesn’t use it. “Please” can be put in different places: at the start, end or before the verb Asking and Giving Permission 9 Ex: - Please can I borrow your car? - Can I please borrow your car? - Can I borrow your car, please? In addition, a more important way of showing politeness is the tone of intonation and voice. Even if a person use the word “please”, he/she can sound rude if his/her pronunciation is not correct. One characteristic difference from asking for permission in English is the word “có thể” (can, could, may, might…) used in Vietnamese. It doesn’t mention different degrees and types of modality. It just makes the permission more polite. Ex: Tôi có thể giúp gì cho bạn? (May I help you?) Furthermore, it’s interesting to note that, on the semantic level, the word “xin phép” is used not only to ask for permission but also to convey the meaning of saying goodbye. The expressions containing the word “xin phép” are employed to ask for permission from the authority, elder and superior. Ex: Em xin phép thầy cho em ra ngoài ạ? (May I go out?) In other cases, Vietnamese people want to show the courtesy and respect when saying goodbye. Therefore, they use expressions like this: Ex: - Xin phép bác con về (It means: chào bác con về.) - Xin phép mọi người mình đi trước (It means: chào mọi người mình về.) They are not expressions of asking for permission. Surprisingly, they are greetings. People often say these expressions with a smile or nod. Asking and Giving Permission 10 When it comes to giving permission, Vietnamese people express a preference for these words or expressions: “Ừ, được, được mà, không sao đâu, cứ lấy đi, cứ làm đi, cứ tự nhiên…” More interestingly, they also have the habit of adding the words including particles which express attitude and feeling toward the addressee:” dạ, vâng, ạ, ờ, ừa…” Ex: Dạ, được ạ! Meanwhile, in response to asking for permission, people in English-speaking countries seem to use these expressions frequently. (1) Yes: used when you are giving permission (2) Of course: used for giving someone permission in a polite way (3) Certainly: used for expressing agreement or giving permission (4) All right: used for saying that you will allow someone to do something, or you do not mind if they do it (5) If you want: used for giving permission or agreeing with a suggestion that someone has made (6) By all means: used for politely agreeing with someone, giving permission or saying “yes” (7) As you wish: used for telling someone that they can do or have whatever they want (8) I don’t see why not: used for saying “yes” when someone asks for your permission (9) Help yourself: used for giving someone permission to do or use something (10) If you (really) must: used for telling someone that it is all right to do something, even though you does not want them to do. Asking and Giving Permission 11 It’s interesting to note that in English, people can not know the power relations (social status or age) and relationship (close, normal or distant) between two speakers because the word “yes” can be used to give permission in all cases. In contrast, in Vietnamese, people may focus on the words “dạ, vâng, ạ, ừ, ờ,…” to know power relations and relationship between interlocurs. Ex: A conversation between grandparent and nephew Grandparent: Nội vào phòng con được chứ? (Can I come in?) Nephew: Dạ, nội vào đi ạ! (Yes) Ex: A conversation between two close friends F1: Bạn cho mình mượn tập nghen? (Can I borrow your book?) F2: Ừ, bạn lấy đi (Yes) In Vietnamese culture, people are willing to avoid unpleasantness by giving permission although they don’t want. This contradiction can lead to great misunderstandings. Therefore, “Yes” may not mean “Yes”. When Vietnamese people say: “No problem”, it can mean “Yes, there is a problem”. (“Vietnam,” n.d.). In this case, double and even triple check should be kept to maintain social rapport It’s clear that the English and the Vietnamese pay regard to the custom of asking for permission. They consider the choice of expressions very carefully. The way English people and Vietnamese people employ asking permission speech act is influenced by two factors: power relations (social status or age) and relationship (close, normal or distant) between interlocutors. However, the characteristic feature which makes English different from Vietnamese is the use of modal verbs. They are used to ask for permission with Asking and Giving Permission 12 different degrees and types of modality. Meanwhile, Vietnamese people have a habit of adding the particles “dạ, ừ, ạ, nhé...” to the expressions of asking and giving permission to show respect, courtesy or intimacy. One another difference between Vietnamese culture and English culture which affects the use of language is that Vietnamese people rarely refuse permission. They don’t want to create unpleasant and threatening atmosphere during conversation. Sometime, they give permission to maintain social rapport and satisfy the addresser’s positive face. To some extent, this should be avoided because it can cause great misunderstandings. In conclusion, “Language is a system of signs that is seen as having itself a cultural value” (Kramsch, & Widdowson, 1998, p. 3). Vietnamese culture is quite different from English culture. That’s why the way people ask for permission and give permission are not similar. Learners should take notice of that to achieve the success in learning the target language. When it comes to learning a second language, one of the problems learners have to face with is the influence of the first language and culture on the second language use. As a consequence of this problem, learners are not confident when communicating or even cause pragmalinguistic and sociopragmatic failure. To overcome the above difficulties, I would like to discuss some implications for language teaching and learning based on contrastive analysis between Vietnamese and English asking and giving permission. Firstly, it is necessary for English teachers to raise students’ awareness of culture similarities and differences between patterns of asking and giving permission in Asking and Giving Permission 13 English culture and Vietnamese culture. Teachers can combine many suitable teaching ways to help learners understand the conflicting patterns. For example, teachers can explain, describe, illustrate…Learners must be well aware of the influence of the culture on language to avoid communication breakdown or offence and converse with native speakers of English successfully. Secondly, English teachers should supply input as much as possible in order to improve students’ ssociopragmatic and pragmalinguistic competence. Teachers can apply the progress of technology to language teaching. Teachers compile and design real situations based on the Internet, on TV…for use in class. Besides, teachers need to provide more options for asking and giving permission to satisfy the requirements of everyday interaction. Finally, teachers should create communicative opportunities for students to practice asking and giving permission in English. Through role play, interview, dialogue, survey,…, students have chance to use the expressions they have learnt in real situations. Significantly, they know how to choose suitable expressions in different situations. Thanks to that, students are able to engage in successful communication with native speakers. These are some suggested activities I collected on the Internet to serve the needs of language teaching and learning. Activity 1 : Work in pairs and practice the dialogues For the lower level students: (a) F1: Can I move your card? F2: Yes, you can. Asking and Giving Permission 14 (b) F1: May I move your card? F2: Yes, you may. For the middle level students: (a) F1: Is it ok if I move your card? F2: Yes, it is ok. (b) F1: Do you mind if I move your card? F2: No, I don't mind. (c) F1: Would it be okay if I move your card? F2: Yes, it would be ok. For the more advanced level students: (a) F1: Would it be alright if I moved your card? F2: Sure, it'd be alright -OR- Of course it'd be alright. (b) F1: Would you mind if I moved your card? F2: No, I wouldn't mind. (c) F1: If you don't mind, I'd like to move your card. F2: Sure, I don't mind. (d) F1: Would it bother you if I moved your card over there? F2: No, it wouldn't bother me at all. (e) F1: Is it alright to move your card so I can pick up my card? F2: Sure, it's alright Activity 2: Many times, hotel staff will find themselves in situations where they will have to take some action that will effect the guest. In these cases, the staff should politely ask the guest for their permission before taking any action. The guest Asking and Giving Permission 15 may also ask permission to do something. It is only polite to ask for their permission before doing so. There are several expressions that can be used for asking for permissions. Look at the expressions below. Expressions Possible responses Is it OK if . . . I really wish you wouldn’t. Do you mind if . . . No, I don’t mind. Go ahead May I . . . Sure, no problem. Would it be a problem if . . . No problem at all. Would it be OK if . . . No, please don’t I would prefer that you didn’t. Dialogue: Work in pairs and practice the dialogue (a) Staff: May I pour you more wine, ma’am? Guest: Sure. (b) Staff: Do you mind if I clean the room now, sir? Guest: Actually, would it be possible for you to come back in half an hour? Staff: No problem, ma’am. (c) Guest: May I borrow you pen. Staff: Absolutely sir, here you go. (d) Guest: Would it be a problem if I left my luggage here for a few minutes? Staff: No problem at all, sir. I’ll, keep on eye on it. (e) Staff: Is it OK if I make a copy of your passport? Guest: Sure, whatever you need. Conversation Activities Asking and Giving Permission 16 1. Practice using the above expressions by having a dialogue similar to the ones above with a partner, one partner taking the role of the guest and the other the role of the staff. For additional practice, switch roles. Practice the dialogue several times, trying to use all of the expressions noted above. 2. Role play the following situations with a partner, one person taking the role of the guest and the other person taking the role of a hotel staff. Permission by Staff - Move some luggage out of the passage way - Open a window - Refill a coffee cup - Pull down a shade - Get their room key or card Permission by guest - Leave bags behind a counter - Smoking in a restaurant - Borrow a pen - Take newspaper from lounge to read in room - Leave a message for a friend Asking and Giving Permission 17 References Vanderveken, D. (1990). Meaning and Speech Acts: Principles of language use. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Eisenstein, M. (1989). The Dynamic interlanguage: empirical studies in second language variation. New York: Plenum Press. Hinkel, E., & Long, M., Richards, J. (Eds.) (2006). Culture in second language teaching and learning. Culture And The Individual, 2. Hornby, A., & Wehmeier, S., Ashby, M. (Eds.) (2000). Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary (6th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press Nguyen, N. Y., Nguyen, V. K., Vu, Q. H., & Phan, X. T. (2010). Vietnamese Dictionary (9th ed.). HoChiMinh, City: Vietnam National University Publishing House Soehartono, & Sianne (2003). A Study of asking for permission expressions produced by the Chinese and Javanese students of SMU Kristen Petra 3, Surabaya. Retrieved December 4, 2010, from http://repository.petra.ac.id/2579/ Samover, L.A. & Porter, R.E. (2000). Intercultural communication: A reader. USA: Wadsworth Publisher, 67-68. Huynh, D. T. (n.d.). Social relationships. Retrieved December 6, 2010, from http://www.vietspring.org/values/social.html Vietnam. (n.d.). Retrieved December 1, 2010, from http://www.ediplomat.com/np/cultural_etiquette/ce_vn.htm Kramsch, C. & Widdowson, H. (Eds.) (1998). Language and Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press.