Chapter 13 Honing Our Sweeter Skills (Days 46 to

advertisement

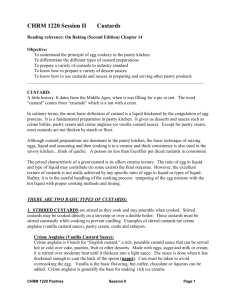

Chapter 13 Honing Our Sweeter Skills (Days 46 to 50) The final phase of our training program, a few days of making baked goods, pastries, and sweets, is the dessert end of the menu. We’re introduced to choux, a simple pastry, but one that’s very difficult to make. It’s one of the cornerstones of the French pastry château. The choux is the little round pastry puff that is the base of many of the decadent concoctions that we all love. The patisserie in France is one of my favourite destinations. Only in France could you have a shop that specializes in desserts. Hundreds of desserts, all lovingly made in the dark of night, freshly displayed each morning like fashion models on a runway and, when sold, carefully wrapped and presented to the purchaser with the pride, care, and attention matched only by Japanese gift-givers. To learn to make choux is to open the door into that patisserie. Chef Patrice promises that we’ll all make choux several times on his watch. It requires a short list of ingredients: water, butter, salt, sugar, flour, and eggs. Gathering the mise en place is crucial, because steps move forward at a very demanding and specific pace. If you don’t have everything ready in advance, your risk of failure rises exponentially. Even the piping bag has to be set. Double-baking pans are necessary because of the high heat in the oven. Chef Patrice walks us through each stage of our preparation and execution to give us a marker for what we need to accomplish to be successful. Finally, we pipe the choux onto the baking tins and pop them into the oven. My first attempt is successful. Although large and slightly misshapen, they’re light, empty in the centre, and an inviting brown colour. Choux pastry must be empty inside. They’re a vessel for carrying goodies. They must taste perfect in their own right, but they’re produced to be filled with various concoctions and to become their better known final transformations – cream puffs, profiteroles, and several other French celebratory sweets. Chef demonstrates the fillings for that empty space inside the choux. First, he shows us how to make crème Chantilly. Basically, it’s whipped cream with some sugar – simple and easy to make, especially with a KitchenAid mixer. We also make crème Anglaise and pastry cream, which are necessary recipes for any chef who makes desserts from scratch. We learn to make quick breads. A quick bread uses some combination of baking soda and/or baking powder but no yeast to provide a chemical reaction that produces carbon dioxide, a gas that lightens and aerates any bakery product. Heat enhances and accelerates the process. These products are characterized by careful measurement and mixing of ingredients in precise formulas according to strict and careful procedures. We make cranberry muffins, cornbread, and sour cherry scones. These are all quick breads. The cornbread is delightful. We enhance it with the addition of some hot green peppers left over from our Indian cooking lessons. Who says we can’t be a bit creative? Culinary chefs describe pastry-makers as glorified chemists, slavishly adhering to formulas set down for them. By contrast, these chefs see themselves as artists, carefully adjusting a myriad of factors to deliver a perfectly tasting dish that’s unique. We learn to strictly adhere to recipe instructions in pastry-making and baking, because failures can’t be tinkered back to life. If it calls for eggs no allowance for mistakes, wrong measurements, substitute ingredients, or changes in procedures. Cooking and ingredient temperatures must be followed exactly. A flop usually goes in the garbage. In a restaurant, these flops are time-consuming, expensive, and embarrassing. Keeping a customer waiting while you redo the dessert doesn’t lead to return customers. If you do exactly as told, you can make a dessert that will weaken the knees of grown men. Who knows what a good dessert does to women? Baking and pastry-making offers some long periods of waiting between stages of the baking process. Dough must be proofed, buns must rise and be punched down, and baking times can be long. It allows us to talk. During one of these breaks, Chef Patrice talks about changing traditions in cooking. “Few of my students come to this school with much experience cooking with their family,” he says. “They do not learn to cook at home at an early age, and not many of them sit down for family meals anymore. “We learned to cook and we ate together as a family,” he reminisces. “We shared meals at home, and we had family events at restaurants only once in a while. Every celebration involved food and family.” My remembrances are similar. We all ate at home, and we all ate together. My mother made almost everything from scratch. She made bread weekly. Every Friday afternoon, we came home to a house that smelled like a bakery. Bread was everywhere, cooling and set to be bagged for the freezer. After making the bread, she usually made a tray of cinnamon buns. They would still be warm when we came in the house, and they became our after-school snack. We learned our way around the family kitchen and learned to cook serviceable meals. By the time I left home, I could cook pretty well. A few of my student colleagues knew how to keep from starving, having mostly learned from their moms along the way. Baking brought back a flood of memories of learning to cook as a child. It was reassuring that the lessons learned long ago had stayed with me, and that those traditions of cooking with friends and family were now back in vogue. Adventures in baking continue, and we create dessert after dessert. We work pastry dough, using pastry shells to make flans, fruit creams, and other delicacies, including one stuffed with frangipane. Frangipane is one of those concoctions that only the French could have dreamed up. It’s a gooey creation of eggs, sugar, flour, and ground almonds that can be used to fill a cavity in any pastry you wish. Then we master custards. My favourites on the dessert menu and the cornerstones of my guest menu for the next decades are laid out before me. Crème caramel, crème brûlée, pastry creams that fill the choux, and of course, crème Anglaise – they’re all here. There’s a world of custards, and I hope to master them all. We make crème caramel and crème brûlée first (recipes are in the Appendix). While everything ends well, we have a few near misses. The simplest things destroy a simple recipe, and mine are some classic rookie errors. I have to make molten caramelized sugar to pour into a ramekin – the first step in making crème caramel. It’s simple. Put some sugar into a saucepan and add water, then cook it until the water evaporates and the sugar caramelizes and turns a delightful amber colour. Next, put the saucepan on ice for a moment to arrest the caramelization process, and pour the caramel sauce into a ramekin. I try and fail twice. The first time, I use too little water and stir it with a wooden spoon. It’s not supposed to be stirred with anything, and it crystallizes harder than diamonds before it turns amber. I start over. I wash the saucepan out and remeasure and replace all the ingredients. Clean saucepan on the stove, I add water and sugar. All it does is froth. The saucepan isn’t clean enough, and I have contaminated the sugar solution. So, I start a third time. I clean the pot thoroughly this time. I add sugar and water, then heat the sugar solution in the saucepan. For a moment my culinary future is suspended between survival and abject failure. I look at the pan, and it’s working! The sugar water caramelizes nicely, turning golden amber. I rush to cool the pot and capture the perfect colour, setting it into an ice bath. Oops, I cool it too much and my caramel hardens. I slowly reheat the pot so as not to deepen the amber colour or burn the caramel. I finally pour a few ounces of gorgeous, pure, amber caramelized sugar into the bottom of our two ramekins. Not bad for a rookie on the first day of custard school. It takes three attempts, three times as long, and three times the ingredients, but I finally have caramel for my crème caramel. Are all my desserts going to be this cruelly challenging? At least I don’t cry. Apparently, as in baseball, there’s no crying allowed in cooking. I don’t swear or yell at my pots, my stove, or my station mate. I don’t lose it and run screaming from the kitchen. I don’t panic – completely. Well, okay, a little. It might be a bit grandiose to quote Rudyard Kipling at this point, keeping my “head when all about you are losing theirs” . . . blah, blah, blah. Since it isn’t life-threatening, caramelizing sugar should not be a drama. There’s something about the kitchen that fuels such meltdowns. Beside us, Felix and Antonio, another top student, are charging ahead. They’re a good team. They’ve done both their crème caramel and their crème brûlée without a hitch and are getting ready to put them in the oven. They need ours to go in the oven we share, but because of my do-overs, we’re way behind. We all decide they should go ahead, and we’ll find another oven. Felix loads the oven with his completed crème caramel and crème brûlée. Then he, too, confronts the cruel nature of fate. A splash of water in the bain-marie, a heated, shallow, water-filled pan that provides a temperature-controlled bath for cooking the custard, spills into his crème brûlée as he’s loading it into the oven. We’ve been told that if water contamination occurs, the crème brûlée will not set. We must throw it out and start over. I’m just putting my crème brûlée together when this happens. Felix has some of his original recipe left over and, combined with mine, we end up with four ramekins of crème brûlée, enough for both stations. We’re back in the game. We pop them straight in the oven. Over the rest of the afternoon, we make several other pastries, cook a rather elaborate dinner for ourselves, and watch a few demos. Luckily, we remember to check the crème caramel and crème brûlée in the oven and find they’re done. They’re removed carefully from the water bath and put in the fridge. After dinner, we go back to the kitchen for a demo from Chef Patrice on how to remove the crème caramel from the ramekin without breaking it into pieces. Broken crème caramel in a restaurant goes in the garbage. At home, we change its name to pudding and eat it. The crème brûlée is easier to complete and much more fun. It stays in the ramekin, and we spread a thin dust of sugar on it, then use the blowtorch to caramelize the sugary surface to make a hot caramelized crust. This is the most fun of the evening. Chef gives us a moneysaving hint. “If you want to buy a torch to caramelize the sugar on your crème brûlée,” he says, “don’t buy those stupid little flambeaus in the kitchen supply houses. Go to a hardware store and buy a good plumber’s propane torch. Get a flame thrower. It works much better.” Too late, I’ve already bought one of those silly little candle lighters. I’m delighted to be sent to a hardware store to buy kitchen supplies, so I vow to regift the baby torch to an unsuspecting acquaintance. After we each caramelize our crème brûlée, we get to consume as much of our custards as we think healthy, then we clean up. What’s healthy got to do with it? I eat both of mine. They’re both delicious, and I vow to practise making them until they’re perfect. Of course, constant practice demands the custards must be consumed, a necessary consequence of my diligence and desire to learn. In the hour left, we clean up our mess and put the kitchen back in perfect shape, because chef releases us only when it’s in perfect shape. As I walk out into the dark at 8:30 p.m., I feel like I’ve been spit out of a huge spaceship from another planet. I’m out on the street, tired yet exhilarated, beat up pretty bad, yet strangely happy about it all. I look back at what we accomplished in one day, and I realize how far we’ve come since our first day of class. We can multitask – we can prep and cook several recipes at the same time and in sequence. We work as a team, helping each other through each process, making results better, building efficiency. We do most of what we’re doing with more confidence, authority, and certainty. We know when we’ve screwed up, and we can recover. Meltdowns are not allowed. I drop off several tarts and seven choux filled with pastry cream for Kristen and Chris. I’m Mr. Pillsbury whistling “Nothin’ says lovin’ like somethin’ from the oven” all the way home. Call me sentimental, but it feels good. In pastry-making, machines really make sense. I already have my eyes peeled for my next big acquisition – a KitchenAid mixer. It’s a real industrial-strength mixer, with a bowl, a powerful motor, and enough attachments to make bread and pizza dough, grind meat, and whip meringues. They even come in a wide array of colours to match your kitchen decor. So far, it looks like one of these will cost more than my first car, but a serious cook needs professional equipment. Right? During our last night in the teaching kitchen with Chef Patrice, we make ladyfingers for tiramisù. While we’re working, Chef tells us his favourite story of this delicious Italian dessert. At some point in the eighties, a tiramisù craze swept through Vancouver like some flu virus. Every customer wanted it for dessert. Chef Patrice developed a recipe that he could make consistently in his restaurant and added it to his dessert menu. “I didn’t like to serve it,” he says. “It is complicated to make, and the ingredients are expensive.” But his customers demanded it, and he responded and served it up. In the middle of the tiramisù craze, he had a call from a friend who ran a hotel kitchen. The hotel was facing the same demand from their customers, and they were looking to secure a supply of tiramisù. They asked if Chef Patrice could send over a sample of his dessert, then possibly supply the hotel needs. When an opportunity to make a lot of money presents itself, such as Chef’s restaurant supplying a large hotel kitchen with a huge inventory of an expensive dish, it’s gold nuggets on the ground. Chef tweaked his recipe to make it easy to prepare in large volume, sent several samples over, and waited. None were quite what the hotel chef wanted. This went on for a few weeks, with none of his submissions quite hitting the target. In the meantime, a local frozen food supplier had jumped on the tiramisù bandwagon, too. The supplier had called and offered to supply Chef Patrice with his frozen concoction. In exasperation, Chef ordered some, and when it was delivered, he ripped the label off the frozen factory product, repackaged it as his own, and sent it off to the hotel. They were delighted! Could he supply the quantities they needed? Could he name a price? “Yes, yes, no problem,” he said. A deal was struck. Chef then called the frozen tiramisù fellow and cut a deal. “Send me all you have.” he said. “My customers love it.” He even negotiated a lower price based on the high volume he ordered. “It was perfect,” he says. “The frozen food man sent the tiramisù over with no need for logos on the boxes, so I got a better price. I then put my restaurant logo on the boxes and shipped them to the new customer. No one was the wiser, and everyone made money. “I did very well with that tiramisù. Every chef has to be a businessman first,” Chef suggests.