Pakistani English & Creolistics: Sociolinguistics Lecture

advertisement

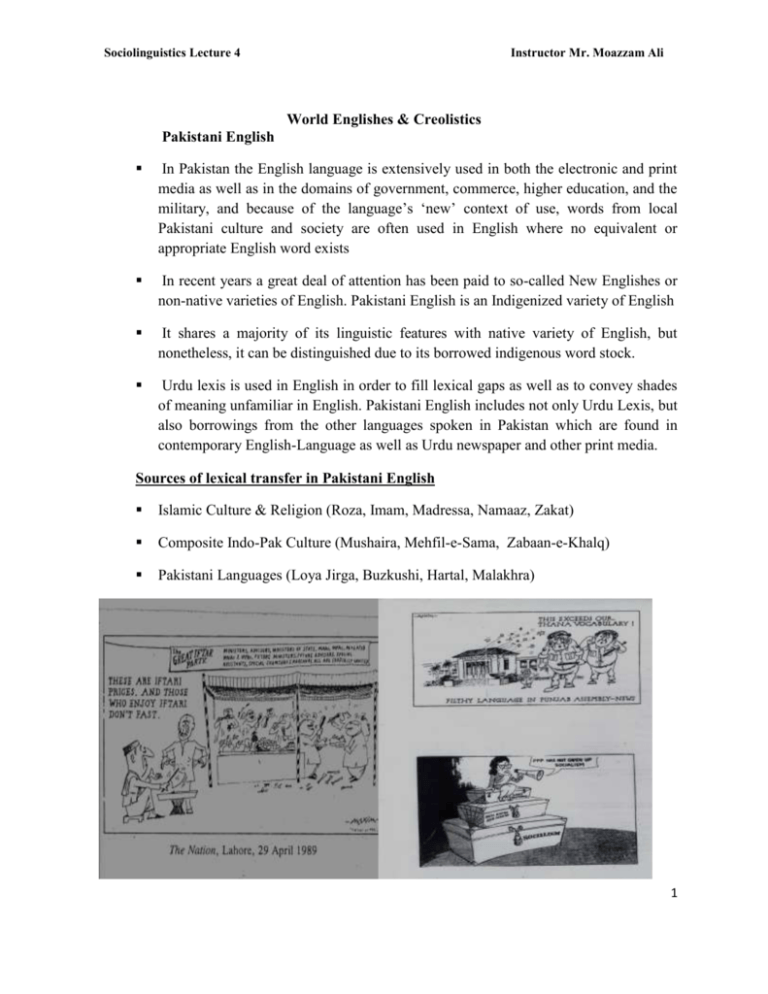

Sociolinguistics Lecture 4 Instructor Mr. Moazzam Ali World Englishes & Creolistics Pakistani English In Pakistan the English language is extensively used in both the electronic and print media as well as in the domains of government, commerce, higher education, and the military, and because of the language’s ‘new’ context of use, words from local Pakistani culture and society are often used in English where no equivalent or appropriate English word exists In recent years a great deal of attention has been paid to so-called New Englishes or non-native varieties of English. Pakistani English is an Indigenized variety of English It shares a majority of its linguistic features with native variety of English, but nonetheless, it can be distinguished due to its borrowed indigenous word stock. Urdu lexis is used in English in order to fill lexical gaps as well as to convey shades of meaning unfamiliar in English. Pakistani English includes not only Urdu Lexis, but also borrowings from the other languages spoken in Pakistan which are found in contemporary English-Language as well as Urdu newspaper and other print media. Sources of lexical transfer in Pakistani English Islamic Culture & Religion (Roza, Imam, Madressa, Namaaz, Zakat) Composite Indo-Pak Culture (Mushaira, Mehfil-e-Sama, Zabaan-e-Khalq) Pakistani Languages (Loya Jirga, Buzkushi, Hartal, Malakhra) 1 Sociolinguistics Lecture 4 Instructor Mr. Moazzam Ali Semantic Aspect of Lexical Transfer Lexical transfer or borrowing is generally found where lexis refers to culture-specific concepts. The notion of achieving greater degree of clarity through the use of borrowing Lexis in journalistic writings can be well illustrated by the given example. Some loan words, like chaddar, mazar, maulvi, chittar and parchi, are used in variety of contexts in Pakistani English in both their literal as well as figurative senses. It is also related that he (Haddu Khan) would begin his khayals in a very restful and slow tempo. After singing both asthai and antara in that way he would sing boltaans and taans, and then the slow khayal would be followed by a fast chhota khayal. (The Frontier Post) Translations of the music lexis in the above given example cannot capture the true essence of such lexis. 2 Sociolinguistics Lecture 4 Instructor Mr. Moazzam Ali Grammatical Aspect Lexical transfer is frequently accompanied by structural changes in which Urdu borrowings under go a morphological restructuring according to the grammatical rules of the recipient language. Example: Big Jagirdars (Landlords) heartlessly oppress poor people living on their land. Agitational politics, jalsas (meetings) and jallooses (processions) have become the preoccupation of political party workers in Pakistan. Islamic lexis; on the other hand, often take Arabic plurals. consider, for example, the following Arabic plurals ending in -een and –aat. 1) Four Mujahideen embraced shahadat. 2) Takbiraat were recited after Eid-prayer. Urdu noun compounds borrowed into English frequently contain the Persian ezafe (-e- or -i-) construction (meaning ‘of’) or the Persian co-ordinating conjunction -o- (meaning ‘and’), while the Arabic article -ul- (meaning ‘of’) often serves as compound enclitic between two nouns. 3 Sociolinguistics Lecture 4 Instructor Mr. Moazzam Ali Borrowing as an Abrogational Tool Abrogation of language refers to the practice in vogue in the post-colonial literatures to defy the notions of ‘centrality’ and ‘purity’ as far as Standard English is concerned. This practice is a major step towards the process of decolonization. 4 Sociolinguistics Lecture 4 Instructor Mr. Moazzam Ali Many Pakistani writers use Urdu lexis as an abrogational tool in their English writings. Some of the examples from Bapsi Sidwa’s ‘Crow Eater’ are cited below where she uses Urdu lexical items as an abrogational tool. As soon as we are settled near a fire temple, I will order a jashan of thanks-giving at our new home. (pg 17) ‘Why not? Ask him to see me at thana tomorrow morning.’ (pg 118) At home she was full of prattle about the mela. (pg 229) He wished for the tenth time he were a Mohammedan and could cover her up in a burqa. (pg 240) He was wearing loose cotton pyjamas and a sleeveless V-necked sudreh.( pg. 283) Lexical Integration Urdu borrowings are integrated into English in many ways. Pakistani journalists writing in English, for example often indicate the degree of integration of a particular Urdu lexical item through the use or non-use of certain graphic conventions. Some of the conventions used to write Urdu lexis in Pakistani English dailies include italics, single or double quotation marks, capital or bold lettering, and underlining. Pidgins, Lingua Franca and L2 A variety of language without native speakers which arises in a language contact situation of multilingualism, and operates as a lingua franca. Pidgins are examples of partially targeted or non-targeted second-language learning, developing from simpler to more complex systems as communicative requirements become more demanding. Pidgin languages by definition have no native speakers, they are social rather than individual solutions, and hence are characterized by norms of acceptability. (Peter Muhlhausler; 1986: 5) The word pidgin, formerly also spelled pigeon derives from a Chinese (Cantonese) language which means ‘business’ In an educational publication related to vernacular languages in Paris 1953, UNESCO defined a lingua franca related to vernacular languages as ‘a language which is used habitually by people whose mother tongues are different in order to facilitate communication between them’. Pidgin Classification according to Grammatical Complexity A jargon (or pre-pidgin) has relatively unstable structure, draws on a limited vocabulary and is frequently augmented by gestures. A stable pidgin (usually just labeled ‘pidgin’, and to which Muhlhausler’s definition best applies) is one which has a recognizable structure and fairly developed vocabulary, but which is in practice limited to a few domains (for example, the workplace, a marketplace and so on). An expanded pidgin is one which has developed a level of sophistication of structure and vocabulary as a consequence of being used in many contexts, including 5 Sociolinguistics Lecture 4 Instructor Mr. Moazzam Ali interpersonal and domestic settings, as well as some formal uses like public speeches or political pamphlets. Creoles are languages which develop out of pidgins and become the first language of a speech community. Pidginization The process by which a pidgin develops is called pidginization. This process of pidginization involves: Admixture Reduction Simplification Creation of Pidgin and Creoles Pidgins and creoles arise out of a diversity of circumstances, including certain types of trade, some situations of war and large-scale movements of people. We shall sample some of these below. New World Slavery In the seventeenth century, Europeans established settler colonies in the New World in order to develop plantations for crops like tea and tobacco. Many indigenous peoples of the Caribbean (for example the Carib Indians) resisted attempts by the European colonists to enslave them, and were often decimated in the process. Those who survived often fell prey to European diseases. The plantation involved the use of imported labour on a massive scale under the control of small numbers of European masters. The Sale Triangle (Europe – Africa – ‘New World’) 6 Sociolinguistics Lecture 4 Instructor Mr. Moazzam Ali Creolists are concerned with the type of communication that must have taken place not only between slave master and slave (‘vertical communication’) but also between slave and slave (‘horizontal communication’). Since masters and slaves did not share a common language, and slaves from different areas would also have had difficulties in communicating with each other, it was inevitable that a pidgin should develop. One unresolved question is whether this pidgin crystallised in the slave factories or during the middle passage or only in the New World plantations. Sociolinguists now accept a dichotomy between fort creoles and plantation creoles. The former developed at the fortified posts along the West African coast, where European forces held slaves until the arrival of the next slave ship (Arends 1995: 16). Guinea Coast Creole English, according to Hancock (1986), is one such fort creole. Plantation creoles, which are more numerous, evolved in the New World colonies, under the dominance of different European languages. These languages are called superstrate languages, since they were socially dominant, in contrast with the substrate languages of the slaves. Under these conditions, a pidgin is assumed to have evolved for both vertical and horizontal communication, drawing on elements from various languages including several African languages and the dominant European language. Trade Pidgins may develop in certain types of trading activities where several linguistic groups of people are involved and interpreters are initially unavailable. Naga Pidgin is a contemporary pidgin of the mountain regions of north-east India, spoken by people in Nagaland and Arunachal Pradesh. It seems to have originated as a market language in Assam in the nineteenth century among the Naga people. It is based on Assami (or Assamese), an Indo-European language of Assam, whereas the Naga people speak Tibeto-Burmese languages which are historically unrelated to Assami. Today the pidgin serves as a linking language (or lingua franca) between people who have about twentynine distinct languages among them (Sreedhar 1974). It is being creolised among small groups like the Kacharis in the town of Dimapur, and among the children of interethnic marriages. European settlement The movement of settlers from Europe to places where the indigenous population had not been decimated or moved into reservations, and where a slave population did not form the labour force (e.g. Papua New Guinea, China, India, East Africa), necessitated the learning of the indigenous languages (e.g. of Hindi in North India and Swahili in East Africa). Sometimes pidgins developed especially where contacts between Europeans and indigenous people were restricted to the domain of employment. Fanakalo is a stable pidgin, spoken in parts of South Africa, which probably originated from contacts between English people and Afrikaners with Zulus in the province of Natal in the mid-nineteenth century (Mesthrie 1989). Its vocabulary is drawn mainly from Zulu and to a lesser extent from English and Afrikaans. The structure of Fanakalo, however, seems closer to English than any 7 Sociolinguistics Lecture 4 Instructor Mr. Moazzam Ali other language. This stable pidgin, which later proved useful in the highly multilingual mines of South Africa, shows no sign of creolising. War American wars in Asia (Japan, Korea, Vietnam and Thailand) since the end of the Second World War have resulted in a marginal, unstable jargon or pre-pidgin called Bamboo English. It seems to have been a simplified form of English, with many words taken from local languages (Schumann 1974). Labour migration Within a colonised country, people belonging to different areas or different ethnic groups might be drawn into the work sphere without being overtly forced. Such accelerated contact might necessitate a quick means of communication, giving rise to pidgins. This has happened in many of the Pacific Islands, where a form of pidgin English developed, for example Tok Pisin in the island of Papua New Guinea. Some linguists believe that industrial pidgins have come into being in Western and Middle Eastern centres which have attracted a large, multinational workforce in recent times (see the box on Gastarbeiterdeutsch below). Whether these are pidgins or forms of second-language acquisition that resemble pidgins is not clear. Linguistic Characteristics of Pidgin Since a Pidgin strives to be a simple and effective form of communication, the grammar, phonology, etc, are as simple as possible. Phonology Pidgin consists of basic Vowel, like /a/ /i/ /u/ /e/ /o/ and consonants. There are less codas within syllables (Syllables consist of a vowel, with an optional initial consonant). There are no tones, such as those found in West African and East Asians languages. Stress is at fixed locations. Lexicon Words from lexifier languages and they belong to open classes (nouns, verbs, adjectives). There are no or few prepositions, conjunctions, determiners, etc. Polysemy (water--‘water, lake, river, spring, tear’) Multifunctionality (sik—as verb and as a noun) 8 Sociolinguistics Lecture 4 Instructor Mr. Moazzam Ali Circumlocution (gras bilong fes-- ‘beard’) Compounding (big maus ‘conceited --literally big mouth’) Grammatical Structure Pidgins have very few suffixes and grammatical markers of categories that are mandatory in the ‘input’ languages. Tense often has to be inferred from context in many pidgins, or is expressed by temporal adverbs like before, today, later, by-and-by and already. Sentences are simple and short with no embedding No can----------- cannot. Talk stink---------- speaking bad about someone. Wat doing--------- what are you doing? If I come stay go, an you no stay come, wat foa I go?-----------If I come and you are not there, why should I go? The following is “A Mother Goose” nursery (The Old Woman Who Lived in a Shoe) translated into Hawaiian Pidgin: Dere waz one ol Tutu(Tutu-grandmother) Stay living in one slippa(slippa-sandals) She get choke kids---(choke- a lot) Planny braddahs and one sistah- ( sistah-sister) (braddahs-brothers) (Planny- plenty) But no da poi(Poi-a Hawaiian food made of taro) Den broke dere okoles (Okoles-butt) And sent dem moi moi (Moi Moi-sleep) 9 Sociolinguistics Lecture 4 Instructor Mr. Moazzam Ali Depidginization The linguistic processes of complication, purification and expansion, by which a pidgin or pidginized variety of language comes to resemble or become identical with the source language from which it was originally derived. This may occur if the speakers of pidgin have extensive contacts with the speakers of source language. Depidginization consists of three processes 1. Complication 2. Purification 3. Expansion Creole When a pidgin is acquired as a first language by a generation of children, it becomes a creole. A creole thus, unlike a pidgin, is a natural language. The term comes from the Portuguese crioulo, and originally meant a person of European descent who had been born and brought up in a colonial territory. Later, it came to be applied to other people who were native to these areas, and then to the kind of language the spoke. Creoles are typically classified based on their lexifier language, e.g., English-based, French based, etc. Decreolization Creoles tend to co-exist with their lexifier languages in the same speech community. Since they are based on these languages, at least lexically, they come to be viewed as “nonstandard” varieties of the lexifier language. Under desires for overt prestige, some speakers start to move away from the creole to the standard lexifier language, in what is often called decreolizatoin. Post-Creole Continuum As a result of decreolizatoin, a range of creole varieties exist in a continuum. The variety closest to the standard language is called the acrolect, the one least like the standard is called the basilect, and in between these two is a range of creole varieties that are called mesolects: 10 Sociolinguistics Lecture 4 Instructor Mr. Moazzam Ali <--------------------------------------------------> Acrolect Mesolect Basilect Theories about the Origins of Pidgin Language These theories can be broadly grouped into three types: (1) monogenetic theories; (2) theories of independent parallel development; and (3) theories of linguistic universals. 1. Monogenesis 2. Independent Parallel Development 3. Linguistic Universals References Karchu,Braj B. 1978. The South Asian English, The University of Michigan Press. Kachru , Yamuna. 1980. Aspects of Hindi Grammar.Delhi,1989. Baumgardner, Robert j. 1987. Utilizing Pakistani Newspaper English to Teach Grammar. World Englishes : 241-52 The English Language in Pakistan National Book Foundation, Islamabad Baumgardner, Robert j. 1990. The Indigenization of English in Pakistan .The English Language in Pakistan National Book Foundation, Islamabad. Rehman,T.1992, Pakistani English, NIPS,Islamabad. Todd,L.1987.AnIntroduction to Linguistics,Longman Group Uk Limited. Jack richards,Platt John, Weber Heidi .1985. Longman Dictionary of Applied Linguistics 11