Counseling Students with Emotional and Behavioral Disturbances

advertisement

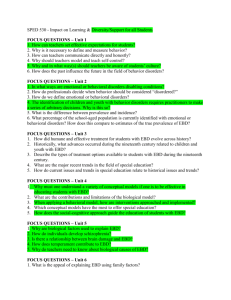

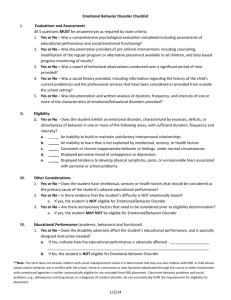

Definition/Diagnostic Criteria Emotional and behavioral disturbance (or EBD) are difficult to identify and classify because they span a range and spectrum of problem behavior, including mood disorders, intense feelings of anger and frustration, anxiety, violent or aggressive behavior and many others. Students who are classified EBD, range in intensity of characteristic behavior, include specific DSM labeled mental illnesses, as well as a range of behaviors that fall into the categorization without falling into a DSM label. IDEA defines children with EBD as meeting one or more of the following characteristics over a long period of time: 1. An inability to learn which cannot be explained by intellectual, sensory, or health factors; 2. An inability to build or maintain satisfactory relationships with peers and teachers; 3. Inappropriate types of behavior or feelings under normal circumstances; 4. A general pervasive mood of unhappiness or depression; or 5. A tendency to develop physical symptoms or fears associated with personal and school problems. Such characteristics must adversely affect a child's educational performance in order for the child to qualify (IDEA, 2004). Students are usually identified by observation in which parents, teachers, and others involved with the child provide checklists and feedback on the frequency, intensity, and range of behaviors identified by IDEA, through the process of a functional behavioral assessment. Prevalence including gender and ethnicity According to the U.S. Department of Education (2001), students with EBD represent 8.1% of all students between 6-21 being served under IDEA. EBD is the third most served disability following speech and language impairments and mental retardation (table II-4, II-20). Most research shows boys who classify as emotional disturbance or behavioral disorders outnumber girls significantly. Compared to the average number of students being served for EBD, more Black students receive services by more than 2%. On the other hand, compared to the average percent of students receiving services for EBD, Hispanic students receive less services for EBD by almost 4% (U.S. Department of Education, 2001, Table II-5, II-22). Impact on the educational pursuits As stated by the first qualifier of the IDEA definition, children who are emotionally disturbed have a difficult time learning and often function two or more years below grade level. The cause for the lower academic functioning varies from student to student. For some the inappropriate social skills prevents success, while for others affective disorders may be part of the cause. According to the U.S. Department of Education (2001) students with EBD are five times more likely to drop out of school at a rate of 51.4% than students with other disabilities (IV-2). Personal/Social development implications (psychosocial) By definition, emotional disturbance is a problem with social behavior and psychosocial skills. Students who are classified emotionally disturbed often act less mature or show inappropriate social skills, respond poorly or inappropriately to discipline and rules, act out in class, act aggressively to peers, and sometimes become very isolated from others. Treatment and Intervention A widely known and researched intervention for students with behavioral problems is called PBIS. Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports is a “school-wide systems of support that include proactive strategies for defining, teaching, and supporting appropriate student behaviors to create positive school environments”. P.B.I.S. is... ● A systems approach for enhancing capacity ● A process for capacity‐ building ● Advocates a continuum of behavioral supports ● Prevention focused ● Instructionally focused ● Based on empirically sound practices ● Supportive of using assessment information ● Focused on establishing organizations with commitment to using effective practices The levels of this systematic approach look like this: ● Universal Interventions ○ For all students; risk status is not considered ● Selected Interventions: ○ For some students; at-risk status is identified for small groups ● Intensive Interventions: ○ For few students; high-risk status is identified for individuals General educational interventions Students that have been determined to have EBD can function in general education classroom with some adaptations. One problem that often arises with this disability is how well the student is able to respond to their peers and in social settings. It is important for teachers to create an environment of inclusiveness and tolerance. Finding ways for these students to stay included in the classroom and take on responsibilities might also help them to stay connected and involved in the general education classroom. Understanding how that specific student is able to learn, whether that be small or large group instruction, or independent learning are important aspects to take into account. Teachers and administrators should develop rules and guidelines that are consistent and appropriate for the entire school. These routine and systematic guidelines should be applied throughout the entire school, from classrooms, to recess, lunch, or the gym. Keeping consistent boundaries can help to teach and explain acceptable and appropriate behavior to students that are struggling. Providing a strengths based perspective for students with EBD is also crucial. Reinforcing good behavior and looking for the students strengths and helping to teach social skills can also be effective tools for these students. Token economies and reward systems are often beneficial tools to use with this population school-wide. School Counselor’s Role and Approaches for Students with EBD School counselors should provide early intervention to provide for support for these students. By providing classroom guidance lessons around healthy social-emotional development. Often students with EBD are struggling with general social skills and teaching these at very young ages can help prevent these behaviors, or find the students that are really struggling and need more assistance. Another form of early intervention that school counselors should implement is training teachers and staff about EBD and how to identify and support the disability. Trainings around crisis management and prevention are also necessary to educate and prepare the staff. School counselors should also be responsible for collaboration, teaming, and advocacy. Because counselors are often the mental health experts in the school, it is important for them to be knowledgeable about community agencies and resources. Teams need to be formed around the student to use all of the available resources and influences. Stakeholders can then share information about the students strengths and abilities as well as getting to the root of their problem behaviors. It is also important to collaborate with teachers so that best practices are being used and all information is being given to best support the student. Counselors are expected to advocates for their students, and to be liaisons between parents, teachers and students when necessary. Specific Interventions Some specific interventions that school counselors should utilize when working with EBD students are peer involvement, and social and coping skills training. Peers are an often easy and effective strategy when working with struggling students. Counselors could pair students in order to model appropriate behavior. Peer tutoring can also be beneficial and some students with EBD would benefit from tutoring or mentoring younger students as well. Running small groups can help students to practice their behavior. These are also helpful in building a support group for the students that are feeling alienated and isolated because of their EBD. Not all students with EBD externalize their emotions and it is important for the school counselor to recognize those students that are struggling more internally and finding effective strategies for them. Groups can also connect students with peers that are similar to themselves and give them a sense of belonging in the school culture. Social and coping skills training is also another important part of working with students with EBD. Often times these students will be on IEP’s and while their academic performance is being taken care of by the SPED department, they are still lacking in the personal and social realms. Helping these students to develop and maintain friendships, resolve conflicts, and increase their independence can be very effective in improving their school performance and experience. Because this condition can be so isolating, it is important to teach coping skills such as stress relief, relaxation, and mindfulness to give the students coping mechanisms to use while at school. These strategies and tools can be extremely helpful for students with EBD. Classroom Guidance/Lesson Plans Students with EBD can lack the necessary skills to cope with even the most basic classroom social demands. Firstly, they commonly come from families who possess few physical and emotional resources with which to support their children's efforts in school; secondly, they have not acquired basic social skills and have found themselves in constant conflict with other people, their peers, their families, and their teachers; and lastly they have or are beginning to establish a history of failing both academically and socially in school. School, with its demands for compliance, cooperation and focused thinking usually becomes an increasingly unattractive place for students with EBD. Because of these deficits students with EBD have spent a small percentage of their school time engaged in productive, on-task behaviors. Commonly students with EBD cannot cope with the demands of their classroom and become extremely disruptive and distracting to the other students in their classroom and through out the school. This failure of coping requires a significant amount of time to be consumed for them, their peers, teachers, staff, and other resources. Devoting school time to learning valuable, academic survival skills for students with EBD can contribute to a more successful school experience. A more focused and intensive approach to teaching social skills for the classroom and encouraging more frequent use of such skills should be emphasized. According to Roy George (1993) the most common social skill deficits that need to be targeted for students experiencing EBD are: Knowing Their Feelings, Using Self-Control, Deciding What Caused A Problem, Staying Out Of Fights, Asking For Help, and Joining In. Oderman, Dillon, & Pratt (2009) suggest that through social skills instruction one can give students more behavioral choices that are healthier and more productive for them and for their overall learning environment. As school counselors it is our job to guide young people towards new ways of thinking, new ways of feeling good and new ways of behaving that can will ultimately have a transformative effect in the classroom and their overall success. Research shows (Oderman et al., 2009) that social skills instruction, in addition to other classroom management practices, can decrease aggressive behavior and increase academic engagement for students who are experiencing EBD. It is important to choose and modify the curriculum and lesson plans for students with EBD based upon their levels development and understanding. For elementary grades it would be important to cover basic and simple social skills; whereas in junior high utilizing basic lessons as reviews while reinforcing behavioral expectations would be important. For students in high school lessons that focus on more advanced skills related to inappropriate language and unhealthy boundaries are critical. The goal is for students to acquire and use these new learned social skills as their behaviors shift in a healthier more positive direction. Additionally the benefits from implementing appropriate and effective lessons can help forge deeper connections with students, making it easier to work through and move past behavioral mistakes in the future. Most importantly applying successful lessons and curriculum to students with EBD can create a learning community where everyone gives and shows respect and feels emotionally secure. References Davis, L.E. (2006). Effects of Social Skills Role Play for Emotional and Behavior Disordered Students. Instructional Technology Monographs 3 (2). Retrieved <July 30, 2012>, from http://projects.coe.uga.edu/itm/archives/fall2006/ldavis.htm. Education.com Fontana, Leonard, Beckerman, &Adela.(2004). Childhood Violence Prevention Education: Using Video Games. Information Technology in Education Annual, 49-62. George, R. (1993). The Development and Implementation of a Group Social Skills Program for Emotionally Disturbed Children in a Special Education School. Master's Practicum Report/Dissertation. Retrieved from Eric EBSCO Database. IDEA of 2004, § 300, D 300-309, a, 3, iii LAUSD Division of Special Education http://sped.lausd.net/ Miller, Lynne Guillot and Rainey, S. John (2008). “Students with emotional disturbances: how can school counselors serve.” Kent State University. http://jsc.montana.edu/articles/v6n3.pdf Odermann-Mougey, M., Dillon, J. C., & Pratt D. (2009). More tools for teaching social skills in schools: grades 3-12. Boystown Press. PBIS.org U.S. Department of Education (2001). Twenty-third annual report to Congress on the implementation of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. Washington, DC: Author.