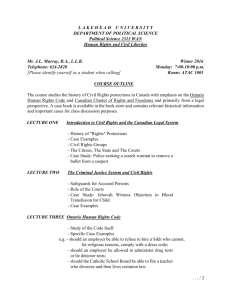

- Human & Constitutional Rights

advertisement