to obtain the paper

advertisement

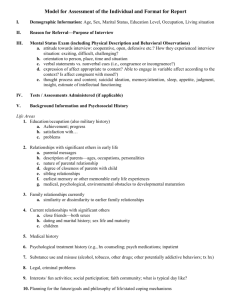

The financial practices and perceptions behind separate systems of household financial management Katherine J. Ashby 1,2 Carole. B. Burgoyne 1 1 2 School of Psychology, University of Exeter, UK Faculty of Law and Social Sciences, University of London, UK Key words: Independent money management, Household financial organisation, Cohabitation Address for correspondence: Katherine Ashby, Department of Development Studies, Faculty of Law and Social Science, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Thornhaugh Street, Russell Square, London, WC1H 0XG, UK. E-mail: KA10@soas.ac.uk; tel.: (+44) 7792445178 1 Abstract Qualitative research in the UK has revealed a diversity of financial arrangements underlying separate systems of household financial management, such as Independent Management (IM) and Partial Pooling (PP). Married and cohabiting couples seem to perceive money in a wide variety of ways, with different implications for how they handle money and for individual well-being. One factor, identified in previous work, is perceived ownership of money, with financial practices differing according to whether couples have distinct, blurred or shared ownership perceptions. The present work aims to build on and extend this research, using data from an online survey study with 190 cohabitants in the UK. The findings reveal that ownership perceptions transcend the money management categories of IM and PP, and can be a significant predictor of the type of contribution cohabitants make towards joint household expenses. Some theoretical implications for the measurement of money management are discussed. 2 1. Introduction ‘Some things are hidden if you just look at the way that money is arranged and you don’t know what lies behind it’ (Interview participant Harry, p.478, Ashby & Burgoyne, 2008) In studies of household financial management, it is often assumed that couples using separate systems of money management, such as Independent money management (IM) and Partial pooling (PP) are behaving as two separate financial entities (Blumstein & Schwartz, 1983; Elizabeth, 2001; Heimdal & Houseknecht, 2003; Oropesa, Landale & Kenkre, 2003; Singh & Lindsay, 1994; Waite & Gallagher, 2000; Vogler, 2005). However, a narrow focus on the money management system and the bank accounts used by couples can conceal some important differences in the way that money is both handled and perceived (Ashby & Burgoyne, 2008, also see Burgoyne, Reibstein, Edmunds, & Dolman, 2007; Nyman, 1999; Nyman & Reinikainen, 2007). One key factor that emerged from earlier research concerns the psychological – or perceived – ownership of money (Burgoyne et al., 2007). These authors identified a spectrum of ownership from distinct (where couples made a clear distinction between joint and individually-owned money), through blurred, where perceptions differed between partners or were in transition, to shared, where all money was regarded as being collectively owned, regardless of its source. In qualitative research by Ashby and Burgoyne (2008) the concept of ownership seemed to be an important determinant for the way that the money management systems of IM and PP operated in practice. Especially when there was a disparity in incomes between partners, there were different implications for individual well-being, depending on whether the couple had distinct, 3 blurred or shared ownership perceptions. Ashby and Burgoyne (2008) concluded that asking questions about ownership perceptions in future research might help to provide a more fine-grained and accurate picture of how couples deal with financial issues (cf. Burgoyne et al., 2006). In a similar vein, Nyman & Reinikainen (2007) advocate examining the meanings of money. In the latter’s qualitative study with married couples they found that the definition of money’s ownership, as ‘mine, yours or ours’ (p65) conferred different meanings upon money, which in turn had implications for how money was used (Nyman & Reinikainen, 2007). For women in particular, they found that having money that was defined as ‘mine’ versus ‘ours’ was an important source of economic independence. This research also has points of contact with Thaler’s (1999) influential work on mental accounting, which challenges the economic assumption of fungibility of money. Mental accounting is ‘the set of cognitive operations used by individuals and households to organize, evaluate, and keep track of financial activities’ (Thaler, 1999, p183). According to this theory individuals can hold a number of separate mental accounts for different expenditures (including for example, household bills, social expenses, personal spending), and the spending from each ‘account’ is constrained in different ways (see Burgoyne, 1995). For example, someone may not want to tap into resources from their household bills account to buy clothing for themselves (see Shefrin & Thaler, 1988). Ashby and Burgoyne’s (2008) research indicates that partners with distinct and also blurred ownership perceptions can hold different mental accounts for shared/joint money on the one hand and personal money on the other. Using data from a survey with 190 unmarried cohabitants in the UK, the present study builds on and extends Ashby and Burgoyne’s (2008) qualitative research on the financial practices and meanings behind IM and PP. 4 1.1 Separate systems of money management Pahl’s (1983) typology was initially developed on the basis of a substantial interview study with married couples to describe the different ways that partners could arrange their household finances. Figure 1 gives an outline of Pahl’s typology and identifies IM as a system where both partners keep their money in separate accounts, have their incomes paid into these accounts and typically do not have access to any joint sources of money (Pahl, 1995). PP has recently been identified for couples who keep a significant proportion of their money independently, but also have a joint account for household expenses (Burgoyne et al, 2007; Pahl, 2005). Couples usually have their incomes paid into their separate account and then transfer an agreed sum into their joint account for collective expenses (Burgoyne et al., 2007). Until recently little research attention has been paid to these separate systems of money management (Elizabeth, 2001). This is in part because the research focus has been on married couples who typically have had such low levels of IM (2% or less), that analysis of this system has often been excluded (Pahl, 1995). However, research with remarried, same-sex, and heterosexual cohabiting couples, has often found much higher levels of separate money management (Ashby & Burgoyne, 2008; Burns, Burgoyne & Clarke, 2008; Burgoyne & Morrison, 1997; Vogler et al., 2006; 2008). Recent studies with newly married couples have also found an increasing use of IM and PP (Burgoyne et al., 2007; Pahl, 2005). The rising use of separate systems of money management has highlighted and heightened the need to explore the financial practices and meanings behind IM and PP (see Elizabeth, 2001). From her qualitative research in New Zealand, Elizabeth (2001) found that IM was adopted by couples in order to avoid financial dependency, and to feel autonomous and independent in the relationship by: (i) maintaining individual 5 Figure 1 Summary of Pahl’s (1989; 1990) typology Money management system Independent management Description Where both partners typically have their own incomes and keep their money in separate accounts. Partial pooling Where partners typically have their own incomes paid into separate accounts, but also have a joint account they each contribute to (typically to pay for household expenses). Pooling (can be joint, male or female managed) Where couples pool all or nearly all of their money into a joint account. The joint pool of money can be managed jointly by both partners or individually by either the male or female partner. Housekeeping or allowance This typically involves a fixed sum being given to the wife for household expenses leaving the rest in the hands of the husband. Whole wage (male or female system) Where one partner manages all of the household finances. Traditionally, in the female whole wage system the husband hands his wages over to his wife (usually minus his personal spending money) and she uses the money plus any of her own to cover the entire household’s needs. In the male whole wage system the man has sole responsibility for running the household finances (which can leave non-earning wives with no access to money for themselves) control over money and (ii) contributing equally towards expenses. However, defining equality in terms of equal contributions without taking account of income can lead to traditional inequalities in access to money, with the higher earning partner (predominantly male) having greater access to and control over their own separate money (Elizabeth). Vogler et al (2006, 2008) draw comparable conclusions in their UK survey study with married and cohabiting couples. They found that IM and PP were most likely to be used by cohabiting respondents when one partner earned more 6 than the other, whereas those who earned similar amounts were most likely to use the joint pool. In a context where men earn more than women, they also argue this can leave the male partner with greater access to discretionary spending money, and allow gender inequalities in the labour market to feed into the household (Vogler et al., 2006; 2008). However, in an in-depth qualitative study, Ashby and Burgoyne (2008) found that it was not always possible to read off financial practices based on the category labels of IM and PP alone. Some couples treated money in a much more collective way than the category labels implied. Indeed just as pooled money could be seen as separately owned (Burgoyne et al, 2007), money held in separate accounts could be seen as belonging to both partners in the couple. Furthermore, it was this sense of ownership that appeared to determine the degree of autonomy for each partner over the use of money (see figure 2, also see Burgoyne, et al., 2007). As figure 2 shows it was specifically those with distinct ownership perceptions who were found to define equality in terms of equal contributions and who were more likely to split the cost of these expenses equally, regardless of each partner’s level of income. In contrast, when there was a disparity in earnings, those with blurred ownership were more likely to contribute proportionally to their earnings, which resulted in the lower earning partner having greater access to spending money than would have been the case if they contributed equally. Finally, for those using IM and PP with shared ownership perceptions, each partner felt they had access to all money, regardless of who earned it. In this way IM and PP resembled the joint pool. The present study investigates these nuances in definitions of equality, and explores whether contributions towards joint expenses differ between those with distinct, blurred and shared ownership perceptions. 7 Figure 2. Ownership perceptions cut across separate categories of money management: Summary of money management categories Distinct - Savings and debts perceived as private matter for the individual rather than a joint responsibility - Partners take financial responsibility for themselves - Pay 50/50 for joint expenses IM Blurred PP Shared - Give versus loan money - More flexible about paying for joint expenses – more likely to pay “roughly” 50/50 or “roughly” proportionally - Ultimately it is the individual’s choice how the money they earned/saved is used - Impossible to distinguish between money in different accounts - Joint decision how the money in each account is used. - Separate accounts are not private. 1.2 The psychology of ownership Etzioni (1991) pointed out that ownership is a ‘dual creation, part attitude, part object, part in the mind, part ‘real’’ (p.466). The psychology of ownership has been studied in a variety of contexts and across a range of disciplines, including psychology, anthropology, consumer behaviour, biology and philosophy (see Pierce, Kostova & Dirks, 2003, for a review). However, this research primarily focuses on the ownership of objects (both material and immaterial), rather than the ownership of money. Pierce, Kostova and Dirks (2003) conceptually define psychological ownership as ‘the state in which individuals feel as though the target of ownership or a piece of that target is ‘theirs’…..The sense of ownership manifests itself in the meaning and emotion commonly associated with my or mine or our.’ Etzoni (1991) and others have highlighted the distinction between psychological and legal ownership and the fact that 8 the former can exist in absence of the latter (and vice-versa). This was certainly true for cohabitants in Ashby and Burgoyne’s (2008) study with shared ownership perceptions who arranged their money in separate accounts. Although these cohabitants may have viewed the money as belonging jointly to both partners, the fact they did not legally have rights to money or property registered solely in their partners name could be problematic in the event of separation, or the death of one partner. This was highlighted in recent case law in the UK, where in an appeal case involving an unmarried cohabiting couple who had separated, the absence of a joint account and the use of separate accounts was taken as evidence of the couple’s financial independence (see House of Lords, 2007, reporting the case of Stack versus Dowden). 1.3 Expectations and hypotheses In light of the earlier findings, discussed above, the following hypotheses were developed: 1) Cohabitants will be more likely to use separate systems of management (including IM or PP), than the pooling, whole wage or housekeeping systems. 2) Ownership perceptions will be independent of the category labels of IM and PP. 3) Perceiving money as shared will be associated with contributing different amounts towards joint household expenses rather than equal contributions. 4) Cohabitants using IM and PP will be more likely to make equal contributions towards joint expenses when (i) they have no children; (ii) partners earn roughly the same amount; and (iii) they perceive money as distinctly owned. In addition to investigating the above hypotheses, the present study examines the relationship between the money management system cohabitants report and other financial information they provided (including for example the bank accounts they 9 had). Versions of Pahl’s (1989; 1995) typology are frequently used in surveys to classify how couples are managing their money. Yet there is very little research on the relationship between participants’ and researchers’ understandings of the money management systems (Sonnenberg, 2008). Exploring ownership perceptions in the present study provided an opportunity to investigate whether participants rely on objective or subjective information when indicating their money management system. For example, when participants perceive money as jointly owned but use separate accounts do they report IM or a pooling system? 2. Method 2.1 Recruitment and Sample Opportunity sampling was used; potential participants were required to be aged 16 years or older, in an unmarried heterosexual cohabiting relationship, and to be resident in the UK. Participants were recruited through a number of methods: a link to the survey was included on the main home page of the One Plus One website (www.oneplusone.org.uk); advertisements were sent via email to staff and students at three Universities in the Southwest (snowballing techniques were also used and those who received the email were asked if they could forward the information to any of their cohabiting friends or family); and posters and leaflets advertising the survey were placed in a number of venues in and around the southwest. 2.2 Participants The final sample comprised 190 unmarried cohabitants. The majority of the sample was white, educated, in full time employment (70.3%) and in a dual-earner relationship. Participants ranged in age from 20-63 years (median of 27 years). The majority of participants (96.8%) had been in a relationship with their partner for over one year. Just over 80% of the respondents had lived with their partner for over one year, 10 with the longest cohabitation being 25 years (median cohabitation length was three years). Just over 10% of the respondents had children with their cohabiting partner and 8.8% had one child or more from a previous relationship. The sample included a disproportionately high number of female cohabitants (79%, 149 out of 190 were female), and because of this any findings regarding gender differences need to be treated with some caution. Nevertheless, the study still provides novel insights into the financial practices and perceptions that underlie separate systems of money management and acts as a departure for further research in this area. It is also worth noting that Ashby and Burgoyne (2008) did not report any gender differences in ownership perceptions in their qualitative study. However, Vogler et al’s (2008) found that unmarried male, childless cohabitants were more likely to report using income pooling, whilst female, childless cohabitants were more likely to report using partial pooling. Yet as the male and female survey participants were not partnering one another in Vogler et al’s (2008) study, it is difficult to conclude that there were gender differences in perceptions of financial arrangements without further research. 2.3 Materials The online survey was 15 pages in length; each page contained a section of questions that participants completed before clicking ‘next’ and moving to the next page. It was possible for participants to go back to earlier sections to change or add to their responses by using the ‘back’ button. The software programme PhP Surveyor was used to facilitate the creation of the online survey (see Kulich, 2006, for further information). The sections of the survey included: (1) cover page, (2) instructions, (3) money management, (4) personal spending money, (5) joint expenses, (6) financial practices and beliefs, (7) control and ownership of money, (8) ownership perceptions, (9) reasons behind separate financial arrangements, (10) reasons for living together, (11) living 11 together background questions, including length of cohabitation, (12) legal understanding and views, (13) demographic details, (14) submission of answers, and (15) final ‘thank you’ page. See Ashby (2008) for further details. 2.4 Measures This study had two dependent measures: household financial management and ownership perceptions. Household financial management was a categorical measure that captured the system of money management that participants said came closest to their own. Initially the following nine categories, based on a modified version of Pahl’s (1989; 1995) typology were included: joint pool (managed by both partners); joint pool (managed by one partner); housekeeping or allowance system; PP (with equal contributions for joint household expenses); PP (with different contributions for joint household expenses); a version of pooling or PP where participants pool nearly all of their income but keep some separately for personal spending; IM (with equal contributions for joint household expenses); IM (with different contributions for joint household expenses); or another arrangement. For the final analyses household financial management comprised only five categories. Cohabitants using a jointly managed pool, a pool managed by one partner, or a version of pooling or PP where the majority of money is pooled but some is kept separately for personal spending1, were all included under one category of ‘pooling.’ Additionally, the housekeeping system was excluded from the analyses due to the small number of cohabitants using this system. Ownership perceptions. 17 ownership items were designed on the basis of Ashby and Burgoyne’s (2008) qualitative study, which represented how cohabitants with either 1 This was decided on the basis of similarities between this version of PP and total pooling, including that participants using this version of PP had their incomes paid directly into a joint account. 12 distinct, blurred or shared ownership perceptions viewed and treated money (see Ashby, 2008). The data were subjected to a principal-axis factor analysis (PAF) (see Table 1, also see Ashby, 2008, for further details). Table 1 PAF Analysis: Factor loadings for Oblimin two factor solution for the ownership perceptions questionnaire: Communalities, eigenvalues and percentages of variance. Item Factor loadings Communality (Pattern Matrix) 1 “I would say that overall I see the 2 -0.803 .71 -0.679 .57 -0.615 .47 -0.614 .72 -0.599 .40 0.549 .41 0.541 .63 0.445 .60 money I earn as money for the relationship rather than just my money” “It does not matter how much we each pay towards joint expenses as long as they all get paid” “I would say my partner and I usually just give rather than loan each other money” “It makes no difference which account or name money is kept in – all the money belongs to both of us” “I feel we are starting to view money as more shared than we used to” “Contributing equally to household expenses and splitting costs 50/50 is very important to me” “We see ourselves as separate from each other financially” “If I borrowed money from my partner I would always pay them back and I would expect them to do the same” “I have the final say over how my 0.952 13 .91 separate savings are used” “My partner has the final say over how 0.910 .89 0.421 .88 0.397 .86 his/her separate savings are used” “The money in my personal account is just mine to spend as I want” “The money my partner has in their personal account is just their money to spend as they want” (*These items were reversed to create the scale) Eigenvalue 8.78 1.27 % of variance 51.69 7.49 Factor correlation matrix Factor 1 2 1 1 .57 2 .57 1 Extraction method: Principal Axis Factoring Rotation method: Oblimin with Kaiser Normalization Factor 1: Shared versus distinct ownership perceptions ( =.88). The items loading highly on the first factor appeared to represent how participants perceived the ownership of money, ranging from a shared view of ownership to a separate (distinct) view of ownership. These eight items (see Table 2) were reversed where necessary and averaged to create a continuous measure of ownership perceptions with scores ranging from 1-5, where a score of one indicated that participants perceived money as shared and a score of five indicated that they perceived it as distinctly owned. A categorical variable for ownership perceptions was also created by dividing the scale into three categories: shared, blurred and distinct ownership perceptions. These were created using the percentiles; those in the distinct ownership group had scores ranging from 0 -2.5; those 14 in the blurred ownership group had scores ranging from 2.51-3.13; and finally those in the shared ownership group had scores ranging from 3.14-5. Table 2 The items that were used to create the ownership measure Different couples often think about and treat money in different ways. Please read the following statements and tick one box to indicate how you treat and/or view money (strongly agree, agree, neither agree or disagree, disagree, strongly disagree) “I would say that overall I see the money I earn as money for the relationship rather than just my money” “It makes no difference which account or name money is kept in – all the money belongs to both of us” “I would say my partner and I usually just give rather than loan each other money” “I feel we are starting to view money as more shared than we used to” “It does not matter how much we each pay towards joint expenses as long as they all get paid” “If I borrowed money from my partner I would always pay them back and I would expect them to do the same”* “We see ourselves as separate from each other financially”* “Contributing equally to household expenses and splitting costs 50/50 is very important to me”* *The scores on these items were reversed when creating the scale 3. Results This section is organised as follows: first, the descriptive survey findings are outlined, including the systems of money management cohabitants used (Hypothesis 1) and cohabitants’ ownership perceptions. Second, the association between money management systems and ownership perceptions is explored (Hypothesis 2). Third, the relationship between ownership perceptions (of those using a separate system of money management) and financial practices (including payment of household and social expenses, and access to money for personal spending) is examined (Hypotheses 15 2 and 3). Next, the results of a regression analysis, exploring the predictors of whether cohabitants using IM or PP made equal contributions (compared to different contributions) towards joint household expenses is presented (Hypothesis 4). Finally, the relationship between the money management system cohabitants said they were using and other financial information they provided is examined. 3.1 How did cohabitants organise their finances? (Hypothesis 1) Table 3 provides information on the percentage of cohabitants using each money management system. As Table 3 shows, consistent with Hypothesis 1, the majority of cohabitants organised some or all of their finances separately from their partner. Overall, just under 50% of cohabitants used PP and just under 30% used IM. The majority of participants using PP and IM paid equal rather than different amounts towards joint household expenses. A further 16.8% of cohabitants pooled all or nearly all of their money (of these cohabitants, over half had a jointly managed pool and the rest had a pool managed by only one partner). Only a very small minority of participants used a version of pooling or PP where participants pool their money together but keep some separately for personal spending, or the more traditional housekeeping system (where one partner takes overall responsibility for all or most of the income and the other receives a housekeeping allowance). Money management and background factors. Our findings indicate that there were no significant differences between male and female cohabitants in the money management system (pooling, IM equal, IM different, PP equal, PP different) used (p>0.05). The majority of both male and female participants used one of the separate systems of money management in comparison to income pooling (21.6% of male participants and 17.6% of female participants used pooling, with the remainder using IM or PP). In relation to cohabitants with children the main differences were between 16 participants using pooling, in comparison to separate systems of money management. Just over 40% (14 out of 34) of those using a pooling system said that they or their partner had children under 18 years. In comparison, only 10.8%, 7.7%, and 6.7% of Table 3 Money management systems used % of Money management system Cohabitants Total N using system Housekeeping/allowance 1.6 3 Pooling (managed jointly) 1.6 19 Pooling (managed by one partner) 6.8 13 Pooling (with money kept separately for personal spending) 1.6 3 PP equal 34.7 66 PP different 13.7 26 IM equal 21.1 40 IM different 7.9 15 Total % 100 100 Total N 190 190 those using PP with equal contributions, PP with different contributions and IM with different contributions, respectively, had children under 18 years. None of those using IM with equal contributions had children under 18 years. This is consistent with research showing that cohabitants with children are most likely to resemble married couples in terms of their use of income pooling (Vogler, 2005). Overall, 37% of participants reported that one partner earned a great deal more than the other, 48% said one partner earned slightly more, and the remainder earned roughly the same. As table 4 shows, when one partner earned a great deal more than the other, income pooling and PP with equal contributions were the most commonly 17 used systems. When one partner earned slightly more than the other, the highest percentage of cohabitants used PP with equal contributions followed by IM with equal contributions (see Table 4). Over half of those earning roughly the same as their partner used PP with equal contributions, followed by IM with equal contributions. Pooling was used by 14% of participants. These findings contrast with Vogler et al (2008) who found that pooling was most likely to be used by cohabitants earning similar amounts, instead our findings show the highest use of income pooling amongst those who reported the greatest disparity in earnings. Additionally, use of PP and IM with different contributions (compared to equal contributions) was highest amongst those who reported a great deal of difference in their earnings. Table 4 Money management systems by earning disparity Money management Earning disparity (percentages) system One partner earns a One partner earns Earn roughly Total Total great deal more slightly more the same % N Pooling 52.9 35.3 11.8 100 34 PP equal 27.3 48.5 24.2 100 66 44 56 0 100 25 IM equal 22.5 60 17.5 100 40 IM different 66.7 26.7 6.7 100 15 66 86 28 100 180 PP different Total N * A chi-square test was not used to explore the overall differences between the groups because some of the expected cell sizes were smaller than 5 (which can result in a loss statistical power; Field, 2005). In the majority of cases (66%) where there was a disparity in earnings between the partners, the male partner was the higher earner (earning slightly, or a great deal 18 more). However, as Table 5 shows, the pattern of use of money management systems was very similar when either the male and female partner were the higher earners. Table 5 Nature of earning disparity (male or female earns more) and money management system Money management Nature of earning disparity (percentages) system Female partner Male partner Total earns more earns more N Pooling 23.1 18 30 PP equal 32.7 33 50 PP different 11.5 19 25 IM equal 17.3 24 33 IM different 15.4 6 14 Total % 100 100 100 Total N 52 100 152 3.3 Ownership perceptions and money management systems (Hypotheses 2 and 3) Respondents were classified as follows: 29% of cohabitants had distinct ownership perceptions, 50% were classified as blurred, and 21% had shared ownership perceptions. There was a significant association between money management system and perceived ownership of money (i.e. shared, blurred or distinct), 2 (8) = 67.35, p<0.001. Figure 3 provides information on money management systems by ownership perceptions, and Table 6 shows ownership perceptions by money management systems. There were some important differences both between and within money management systems. One of the key differences was between those using pooling and separate systems of money management; a much higher percentage of those using pooling 19 viewed their money as shared, in comparison to those using a separate system of money management. Cohabitants using a separate system of management were more likely to have blurred or distinct ownership perceptions. None of the cohabitants with distinct ownership perceptions used income pooling. Table 6 Ownership perceptions by money management system Money management Ownership group system Distinct Blurred Shared Total N Pooling 0 5.7 51 30 PP equal 44.7 44.8 18.4 65 PP different 5.3 17.2 14.3 25 IM equal 42.1 24.1 6.1 40 IM different 7.9 8 10.2 15 Total % 100 100 100 Total N 38 87 46 174 * 2 (8) = 67.35, p<0.001 Consistent with Hypothesis 2, Figure 3 shows differences within the money management systems of IM and PP. Those making equal contributions towards household expenses (using IM or PP) were more similar in terms of their ownership perceptions than those making different contributions towards expenses (using IM or PP). In support of Hypotheses 2 and 3, a higher percentage of cohabitants making different contributions towards joint expenses had blurred or shared ownership perceptions, as compared to those making equal contributions. Additionally, a higher 20 Figure 3. Money management system by ownership category Ownership category (% of cohabitants) 100% 7.5 13.8 90% 29.2 33.3 80% 70% 52.5 60% 83.8 60 Shared 50% 40% 46.7 62.5 Blurred Distinct 30% 20% 40 26.2 10% 20 16.7 8.3 0% Pooling PP equal PP different IM equal Im different Money management system percentage of those using IM and PP and making equal contributions had a distinct view of ownership, as compared with those making different contributions. Therefore the findings show greater similarities in ownership perceptions across IM and PP based on the type of contribution partners made towards household expenses, than between IM and PP per se. Ownership perceptions and background factors. In line with the previous findings regarding the increased use of income pooling amongst participants with children, a higher percentage of cohabitants with children had shared ownership perceptions, compared to those without children. There was also a significant association between ownership perceptions (distinct, blurred or shared) and the sex of the participants, 2 (2)= 7.38, p = 0.025. A higher percentage of female cohabitants reported having distinct ownership perceptions in comparison to male cohabitants (25.5% of female cohabitants were classified as having distinct ownership perceptions, compared to 5.4% of males). Additionally, male cohabitants had a higher percentage of 21 shared ownership perceptions compared to females (37.8% of the male cohabitants were classified as having shared ownership perceptions, compared to 26.2% of the females). However, due to the small number of male cohabitants in this sample, and the fact that male and female participants in the study were not partnering one another it is not possible to draw any general conclusions about such gender differences. There was a significant association between ownership perceptions and earning disparity, 2 (4)= 2.068, p <0.001. In support of Hypothesis 4, a higher percentage (44.9%) of those who reported a large disparity in earnings were classified as having shared ownership perceptions, in comparison to those with a slight difference in partners’ earnings, or those who earned roughly equally (15.9% and 23.3% respectively). There was also a significant association between ownership perceptions and the nature of the earning disparity (i.e. if the female or male partner were the higher earner, or they earned the same), 2 (4) = 1.02, p < 0.05. As Table 7 shows when the female partner was the higher earner, there was a higher percentage of shared ownership perceptions, compared to when the male partner was the higher earner. However, it is also important to keep in mind that this difference could be related to the high number of female participants in the study, who were the lower earner in their relationship. As the lower earner, female partners are perhaps less likely to perceive money as shared, compared to when they are in the higher earner position (see Burgoyne, 1990; 1995). The descriptive findings seem to support this assertion; exploring the results for female participants separately showed that when the female partner was the lower earner, 21.5% reported shared ownership perceptions. 22 Table 7 Nature of earning disparity (male or female earns more) and ownership perceptions Nature of earning disparity (percentages) Ownership perceptions Female partner Male partner earns more earns more Earn the same Total N Shared 37.3 25 23.3 51 Blurred 33.3 54 66.7 91 Distinct 29.4 21 10 39 Total % 100 100 100 100 Total N 51 100 30 181 In comparison, when the female partner was the higher earner, 38.1% of females reported shared ownership perceptions. As already mentioned, caution needs to be taken in drawing any definite conclusions from these findings. However, they do indicate the need to examine potential gender differences in ownership perceptions in future research. In particular it will be important to explore the extent to which partner’s views of ownership coincide, especially where one earns more than the other. 3.4 A closer look at ownership perceptions and the financial practices of those using separate systems of money management (Hypotheses 2 & 3) Exploring payments of joint household expenses in more detail revealed that cohabitants using a separate system of financial organisation in the distinct ownership group were more likely to pay for expenses exactly equally (57.9%), than those who had blurred or shared perceptions of ownership (46.3% and 29.2% respectively). Those with blurred perceptions of ownership were most likely to say they paid for expenses “roughly” equally and to be unsure of the precise contributions they each made (32.9%, compared to 21.1% for those who viewed money as distinct and 29.2% for those who 23 viewed money as shared). In relation to spending on joint social expenses (for example, going out for meals, drinks and cinema trips together), consistent with the findings from Ashby and Burgoyne’s (2008) interview study those with shared and blurred ownership perceptions were the more likely to report that they took it in turns to pay but did not keep track of how much they each contributed (66.7% shared, 54.9% blurred and 36.8% distinct). Cohabitants with distinct ownership were the most likely to pay for social expenses equally: 15.8% of cohabitants with distinct ownership said that they took it in turns to pay and did keep track, whereas only 3.7% of those with blurred ownership said that they paid in this way, and none with shared ownership did. Also a further 26.3% of those with distinct ownership said that they shared the cost of social expenses 50/50, compared to only 4.2% with shared ownership and 3.7% with blurred ownership. Moreover, none of those with distinct ownership perceptions and only 1.2% of those with blurred ownership said that they paid from whichever account had money in at the time (it could be separate or joint), in comparison to 16.7% of those with shared ownership perceptions Ownership perceptions and personal spending money of cohabitants using separate systems of money management. The majority of participants in all of the ownership groups reported that they ‘always’ had access to money for personal spending, however, the percentage was highest for those with distinct ownership: 97.2% reported always having access to personal spending money, compared to 90.9% of those with shared ownership perceptions and 90% of those with blurred perceptions. In relation to source of money for personal spending the main differences were between participants with shared ownership in comparison to those with either blurred or distinct ownership. All cohabitants with distinct and blurred ownership perceptions 24 used money for personal spending money from their own earnings or savings, compared to 87.5% of those with shared ownership perceptions. The remaining 12.5% of those with shared ownership perceptions said that their spending money came from whichever account had the money in at the time (it could be either their own or their partners separate account or a joint account). Overall, in support of Hypothesis 2 these findings indicate that the ownership perceptions of cohabitants using separate systems of money management can have different implications for the way that money is used for various purposes. 3.6 Predicting contributions towards joint household expenses (Hypothesis 4) Hierarchical logistic regression analyses were used to explore which variables predicted whether cohabitants using a separate system of financial organisation (including both IM and PP) made equal contributions, in comparison to different contributions, towards joint household expenses. The first regression tested the effect of ownership perceptions by entering it as a second step (after the variables ‘children under 18’ and ‘earning disparity’). For each of the categorical variables the last named category was the reference group. Previous research has supported the role of the two variables entered at the first step of the regression (children under 18 years and earning disparity) in predicting type of contribution towards joint expenses (see Elizabeth, 2001; Vogler, 2005). Therefore, this procedure was chosen as it enabled the effect of new predictors of financial organisation to be tested (including ownership perceptions), whilst controlling for those which previous research had established as important (see Field, 2005, for discussion of this approach). The variables were entered in the following order (as separate steps) in the way described above: children under 18 years (yes, no) and earning disparity (one partner 25 earns a great deal more, one partner earns slightly more, earn roughly the same); ownership perceptions. The final model: Hypothesis 3 was partially supported; two variables were significant predictors of whether cohabitants using separate systems of organisation made equal contributions (compared to different contributions) towards joint household expenses: perceived earning disparity and ownership perceptions. At the first step, the predictors (children under 18 and earning disparity) accounted for 14.2% of the variance (Nagelkerke pseudo R Square), and 73.4% of cases were correctly classified using this predictor, 2 (3) =14.62, p<0.05 (note, the priori number of cases correctly classified was also 73.4%). The variable ‘children under 18 years’ was not a significant individual predictor of the type of contribution participants made. However, the model at the second step, including ownership perceptions, accounted for 28.1% of the variance (Nagelkerke pseudo R Square), and 79.7% of cases were correctly classified using this model, 2 (1) =16.01, p<0.001. Table 8 shows that one partner earning a great deal more than the other (rather than earning roughly the same) reduces the odds of cohabitants making equal contributions towards joint household expenses by a factor of 0.04 (or 96%), compared to the odds of making different contributions. However, the odds of making equal contributions (compared to different contributions), increases by a factor of 3.14 for every one point increase in ownership perceptions score (where a high score indicates money is perceived as separately/distinctly owned). Another way to understand these results is that cohabitants who have a great deal of difference in their earnings are 3.13 times less likely, and those who have a slight difference in their earnings are 2.44 times less likely, to make equal contributions towards joint household expenses. Also for every one point increase 26 Table 8 Summary of regression predicting equal contributions towards joint household expenses (compared to different contributions) Predictor B SE Wald Exp (B) statistic 95% confidence interval for Exp (B) (a) Children under 18 years Lower Upper 0.26 0.88 0.9 1.30 0.23 7.31 -3.13 1.10 8.17* 0.04 0.01 0.37 -2.44 1.09 5.01* 0.09 0.01 0.74 1.14 0.31 14.46** 3.14 1.70 5.78 (yes) (b) Earning disparity (one earns a great deal more) (b) Earning disparity (one earns slightly more) Ownership perceptions * p < 0.05. **p <0.001 a) The reference category is ‘no’ children under 18 years b) The reference category is ‘we earn about the same’ in ownership perceptions score (where a higher score indicates participants perceived money as distinctly owned) cohabitants are 1.14 times more likely to make equal contributions, compared to different ones. Overall, these findings indicate that cohabitants who earn roughly the same amount, and perceive the money they and their partner have as distinctly (separately) owned are more likely to make equal contributions towards joint household expenses, in comparison to different contributions. 27 3.5 Classifying money management systems In this section the relationship between the money management system cohabitants said they were using and other financial information they provided is examined. Money management system and income/earnings. All of the cohabitants using a separate system of management (IM or PP with equal or different contributions) had their incomes paid directly into a personal account in their name only, as did their partners. In comparison, 41.2% of those using a pooling system had their income paid directly into a joint account (held in joint names) and 55.9% had their income paid directly into a personal account in only their name, as did their partners. Joint accounts: Although the majority of those using a pooling system had a joint account, a substantial minority did not: 20% of cohabitants using a pooling system, 10.6% of those using PP with equal contributions, and 30.8% of those using PP with different contributions said that they did not have a joint account. Additionally, whilst the majority of those using IM did not have a joint account, 17.5% of those using IM with equal contributions and 6.7% of those using IM with different contributions did. This suggests that those participants (without a joint account) who indicated that they used a total pooling or PP system focused on how they perceived money when they chose which arrangement came closest to their own, rather than how money was physically arranged. This is supported by the fact that all of the participants using a pooling system who did not have a joint account were in the shared ownership category (indicating they viewed all of their money as jointly owned). Additionally over 80% of cohabitants using a pooling system that did not have a joint account said that they saw the money in their personal account as belonging equally to both partners. 28 None of the cohabitants using IM who also had a joint account used the latter to pay for joint household expenses. Instead, it was used for a range of purposes including joint savings, house related repairs and joint furniture, and joint holidays. Also one participant said that they used their joint account as an individual account for their own personal spending. Separate accounts: All of the cohabitants using separate systems of management (IM or PP) had personal accounts, as did their partners. In comparison, 34.3% of those using a pooling system had no personal account. Therefore, in line with the typology (Burgoyne, 1995; Pahl, 1989; 1995;), pooling was less associated with participants having their own personal accounts, than separate systems of management. However, the majority of those using pooling did have a separate account and, as mentioned earlier, just over 40% of pooling cohabitants had their incomes paid directly into a separate account in their name only. Yet the findings examined above also revealed that cohabitants using pooling (rather than a separate system of management), differed in how they perceived the ownership of money in their personal accounts. A higher percentage of those using pooling said that the money in their personal account belonged equally to both partners, compared to those using IM or PP. 4. Discussion In line with the existing literature (Ashby & Burgoyne, 2008; Elizabeth, 2001; Vogler, 2005; Vogler et al., 2006; 2008), there was a high level of separateness in the way cohabitants organised their finances. The majority of respondents used IM or PP, and the more traditional housekeeping and whole wage systems had to be excluded from the quantitative analyses because less than two percent were using the former system and none used the latter. 29 However, consistent with Ashby and Burgoyne (2008), cohabitants using separate systems of financial organisation did not always operate as separate financial entities and a more complicated picture emerged; within IM and PP cohabitants handled and perceived money in a range of ways. As predicted, ownership perceptions cut across IM and PP and had different implications for cohabitants’ financial practices and individual access to resources, depending on whether they had shared, blurred or distinct ownership perceptions (this echoes the findings of Burgoyne et al., 2007, with newly married couples). 4.1 Ownership perceptions and financial practices Distinct ownership was related to paying exactly equally towards both joint household and joint social expenses (and being aware of the precise contribution that each partner made). In comparison, cohabitants with shared and blurred ownership were much less aware of the exact amount each partner paid. They were more likely to make different contributions, and say that they paid ‘roughly’ equally or ‘roughly’ proportionally towards these costs. Overall, in terms of paying for joint expenses cohabitants with distinct ownership perceptions more closely resembled the separate financial entities usually associated with separate systems of management, whereas the more flexible approaches taken by those with shared and blurred ownership perceptions more closely matched the financial practices typically associated with total pooling (e.g., see Pahl, 1995; Singh & Lindsay, 1994). In relation to PSM, all of the cohabitants with distinct or blurred ownership perceptions took their PSM from their own earnings or savings. Fewer of those with shared ownership took their PSM from this source, with the remaining participants using whichever of their accounts (joint or separate) had the money in at the time. 30 Cohabitants with shared ownership also reported having slightly less frequent access to PSM than those with blurred or distinct ownership perceptions. These findings support previous research on income pooling showing that when PSM comes from a joint source each partners’ spending can be constrained by feeling that they need to consult one another before making purchases, or the lower earning partner feeling less entitled to spend money that they did not earn (see Burgoyne 1990; Burgoyne & Lewis, 1994). These findings add to previous research by indicating that this impact on personal spending can occur when money is perceived as shared (and is arranged partially or completely in separate accounts), in addition to when it is physically arranged as “joint” or shared (i.e. a pooling system is used). 4.2 Beyond categories of money management In summary, the findings indicate that the category labels of IM and PP can conceal important differences in how cohabitants perceive and handle money. Overall, the findings support the development of a multi-dimensional approach that takes into account how money is perceived, as well as the accounts used. However, in quantitative research, where the typology is the only source of information available, the findings indicate that subdividing separate systems of money management on the basis of whether partners make equal or different contributions towards joint expenses can begin to tap into how cohabitants perceive the ownership of money. This is because, as illustrated above, ownership perceptions relate to cohabitants’ financial practices, as well as how they view their relationship in terms of ideology and permanence. 4.3 Predicting equal contributions towards household expenses To our knowledge, this was the first survey study to investigate which variables predict whether cohabitants using separate systems of management (IM or PP) make equal or different contributions towards joint household expenses. Consistent with the 31 predictions, after controlling for whether cohabitants had children under 18 years, both earning disparity and ownership perceptions were found to play a significant role in predicting whether cohabitants made equal contributions towards joint household expenses. In line with previous qualitative findings (see Elizabeth, 2001), those with a disparity in earning were more likely to pay different amounts towards joint household expenses than those who earned roughly the same amount. Furthermore, when one partner earned a great deal more than the other, cohabitants were more likely to contribute different amounts than when one partner earned slightly more. Cohabitants who viewed money as more distinctly owned were more likely to make equal (rather than different) contributions to household expenses. These findings further demonstrate and support the role ownership perceptions can play in explaining how cohabitants deal with money. Vogler et al (2008) hypothesised that cohabitants’ use of separate systems of money management could reflect a desire by the higher earning partner to retain greater access to and control over separate money. However, the present findings indicate this is not always the case, as those with a disparity in earnings were more likely to perceive money as shared and to contribute different amounts towards expenses. Moreover, the extent to which partners using separate systems of money management feel they have separate control over and access to money seems to depend on how they perceive the ownership of money. On a descriptive level the analyses also suggest potential gender differences in ownership perceptions. First, a higher percentage of men reported shared ownership perceptions (and a lower percentage of distinct ownership perceptions) in comparison to female participants, and second, in cases where the male partner was the higher earner, female participants reported a lower level of shared ownership perceptions, in compared to when female participants were the higher earner themselves. These 32 findings are consistent with Burgoyne’s earlier work on the importance of the rights of the earner, and the finding that even when money is pooled, the partner contributing less (or not at all) can lack the sense of entitlement over money that seems to go handin-hand with earning (Burgoyne & Lewis; Burgoyne & Kirchler, 2008; Pahl 1995). These findings also resonate with Tichenor’s (1999) research showing that women who earned a lot more than their male partners, often defined all assets as joint, in an attempt to protect their husband’s masculinity. However, as mentioned earlier, due to the small numbers of male participants in the sample, and the fact male and female participants were not partnering one another, further work including both partners is required to investigate these potential gender differences in ownership perceptions. Furthermore, additional research is required to explore the relationship between participants’ beliefs about equality, and their actual financial practices. In particular, do those who value 50/50 payments always contribute equally towards joint expenses, even when there is a disparity in earnings? Also do cohabitants that define equality in terms of having equal access to money for discretionary spending, pay different amounts towards joint expenses when there is a difference in earnings? Do partners’ views of the meaning of equality always coincide? 4.4 Classifying money management systems: Exploring the relationship between subjective and objective information Frequently, one of the main criteria used for classifying participants as having a pooling or PP system is the presence of a physical pool of money that both partners have access to (usually a joint account). IM, on the other hand, is distinguished from PP by the fact that participants do not usually have a joint pool of money that they both have access to (Pahl, 1995). However, contrary to these definitions, the present findings revealed that a number of the cohabitants who reported that they were using pooling or 33 PP did not actually have a joint account. This indicates that these participants were relying on how they perceived money, rather than where it was located (that is, how it was physically arranged) when they selected which management system came closest to their own. This is supported by the findings that all of the participants using PP or pooling without a joint account said they viewed the money in their separate accounts as belonging to both partners. In addition, a small number of the cohabitants using IM had a joint account. However, it seems that they did not report they were using PP, as the primary purpose of their joint accounts was not to pay joint household expenses. Instead these participants used their accounts in a range of ways, including for joint savings, joint holidays or as an individual account. As discussed above, the findings on ownership perceptions challenge the assertion that all cohabitants using separate systems of management (IM or PP) operate as separate financial entities. They show that cohabitants within IM and PP perceive and handle money in a range of different ways, and whilst the majority perceive money as distinctly owned, others have blurred or shared ownership perceptions. Cohabitants with different ownership perceptions have varying financial practices and access to money. In particular, as mentioned above, when it came to paying for joint expenses the flexible approach taken by those with blurred and shared ownership perceptions more closely resembled those typically associated with total pooling than separate systems of management. Overall, these findings indicate that cohabitants with blurred and especially shared ownership perceptions (who selected IM or PP), were relying on objective information regarding the accounts they kept money in, rather than subjective information regarding how they perceived the ownership of money (and also how they 34 used money) when they reported which money management system came closest to their own. 4.5 Limitations, strengths and conclusions This study had a number of limitations which merit discussion. First, the hypotheses indicate that perceiving the ownership of money as shared, blurred or distinct, could lead to different financial practices. Whilst this is a plausible prediction based on our earlier qualitative findings, as the data were correlational in nature they cannot be used to support causal interpretations. It is also possible that ownership perceptions are influenced by the financial practices couples adopt. In future work, experimental research designs are needed for more certainty about causal relationships. Additionally, further research is required to investigate the origins of different ownership perceptions, including the extent to which partners believe money should be shared or kept independently in cohabiting relationships (see Burgoyne, Sonnenberg & Routh, 2006). A second limitation relates to the cohabitants who took part in this study. The majority of the sample in the survey study were female, dual-earner couples and had no children. The fact that the majority of participants did not have children was advantageous in allowing an in-depth understanding of this group to be explored. This was especially important because research in the UK has previously focused on those with children, and less detailed information is available on cohabitants with no children. However, this narrow focus means that further research is required to explore how those with children deal with money. This is particularly because when couples have young children they are less likely to be in dual-earner relationships. It will be important to examine how the employment status of each partner impacts on his or her perceptions and use of money. Additionally, as the majority of the sample in the survey 35 were female, the extent to which our findings generalise to a male sample is an important question for future research. Furthermore, including data from both partners in a couple in future research will allow gender differences in ownership perceptions to be fully examined. Despite these limitations, the study nevertheless enabled detailed information to be gathered on the financial arrangements of a larger group of cohabitants than would have been possible with qualitative research. Crucially, the survey made it possible to test if the relationships between variables found in the interview study (with a small number of cohabitants) held up in a larger sample. In terms of theoretical implications for how money management is conceptualised, the findings of both our earlier qualitative research and the present survey study support the need to move beyond Pahl’s (1989; 1995) typology in its current form. Both research studies indicate that the typology is not always able to capture how those using separate systems of management perceive and handle money, and that diversity may be hidden under the category labels of IM and PP (see Ashby & Burgoyne, 2008). Ownership perceptions seem to provide a more consistent picture of cohabitants’ financial practices and individual access to resources than objective information regarding the accounts participants use. The findings support the development of a more holistic approach, which takes into account both how money is perceived and the accounts participants use. In addition to being better suited to the increasingly separate financial arrangements of couples, this approach would also help to resolve any ambiguities regarding the extent to which participants (and researchers in qualitative research) relied on subjective or objective information when classifying a couple’s system of money management. 36 Overall, our earlier qualitative study (Ashby & Burgoyne, 2008) provided a rich base of data from which to develop a detailed measure of ownership perceptions in the present survey. The measure of ownership perceptions needs to be tested rigorously in future research, but it has the potential to provide a fruitful and novel way of capturing detailed financial information, which researchers have not previously been able to capture in quantitative research. References Ashby, K.J. (2007). Money, Cohabitation and the Law: A Story of Diversity. Doctoral thesis, University of Exeter, UK. Ashby, K.J., & Burgoyne, C.B. (2008). Separate financial entities? Beyond categories of money management. Journal of Socio-Economics, 37, 458-480. Barlow, A. (2008). Cohabiting relationships, money and property: The legal backdrop. Journal of Socio-Economics, 37, 502-518. Barlow, A., Burgoyne, C., Clery, E., & Smithson, J. (2008). Cohabitation and the law: myths, money and the media. In A. Park, J. Curtice, K. Thompson, M. Philips, M. C. Johnson, & E. Clery (Eds.), British Social Attitudes: The 24th Report. London: Sage. Barlow, A., Burgoyne, C.B., & Smithson, J. (2007). The living together campaign – An investigation of its impact on legally aware cohabitants. Research report to Department for Constitutional Affairs, 14h February 2007. Retrieved March 1, 2007 from www.dca.gov.uk/research. Blumstein, P., & Schwartz, P. (1983). American couples: Money, work, sex. New York: William Morrow and Company Inc. Burgoyne, C. B. (1990). Money in marriage: how patterns of allocation both reflect and conceal power. The Sociological Review, 38, 634-665. Burgoyne, C.B. (1995). Financial organisation and decision-making within western ‘households’. Journal of Economic Psychology, 3, 421-430. Burgoyne, C.B., & Kirchler, E. (2008). In A.Lewis (Ed), The Cambridge Handbook of Psychology and Economic Behaviour, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp.132-155. 37 Burgoyne, C. B., and Lewis, A. (1994). Distributive Justice in Marriage: Equality or Equity? Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 4, 101-114. Burgoyne, C.B., Reibstein, J., Edmunds, A.M., and Dolman, V.A. (2007). Money management in early marriage: Factors influencing change and stability. Journal of Economic Psychology, 28, 214-228. Burgoyne, C. B., and Routh, D. A. (2001). Beliefs about financial organisation in marriage: The 'Equality Rules OK' norm?' Zeitschrift für Sozialpsychologie, 32, 162-170. Burns, M., Burgoyne, C. B., & Clarke, V. (2008). Financial affairs? Money management in same-sex relationships. Journal of Socio-Economics, 37, 481-501. Elizabeth, V. (2001). Managing money, managing coupledom: A critical examination of cohabitants' money management practices. The Sociological Review, 49, 368-388. Etzioni, A. (1991). The socio-economics of property. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 6, 465–468. Haskey, J. (2001). Demographic aspects of cohabitation in Great Britain. International Journal of Law, Policy, and the Family, 15, 51-67. Heimdal, K. R., & Houseknecht, S. K. (2003). Cohabiting and Married Couples' Income Organization: Approaches in Sweden and the United States. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65, 525-538. House of Lords (2007). Judgements – Stack (Appellant) v. Dowden. Retrieved May 10, 2007, from http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld200607/ldjudgmt/jd070425/stack1.htm Kiernan, K. (2004). Unmarried cohabitation and parenthood in Britain and Europe. Law & Policy, 26, 33-55. Kulich, C. (2006, November). Workshop on PHP Surveyor version. University of Exeter, School of Psychology. Laurie, H. & Gershuny, J. (2000). Couples, work and money. In R. Berthoud and J. Gershuny (Eds.), Seven Years in the Lives of British Families, Bristol: Policy Press, pp.45-72. National Statistics (2005). 2005 Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings. Retrieved Jan 1, 2006, from www.statistics.gov.uk/pdfdr/ashellos.pdf Nyman, C. (1999). Gender equality in 'the most equal country in the world'? Money and marriage in Sweden. The Sociological Review, 47, 766-793. 38 Nyman, C., & Reinikalinen, L. (2007). Elusive independence in a context of gender in Sweden. In J. Stocks, C. Diaz-Martinez, & B. Hallerod (Eds,), Modern couples sharing money, sharing life (pp.41-71). Basingstoke, UK: Macmillan Office of Public Sector Information (2007). Civil Partnerships Act (2004). Retrieved January 1, 2006, from http://www.opsi.gov.uk/acts/acts2004/20040033.htm One Plus One Marriage & Relationship Research. (2007). Welcome to One Plus One: National Information Centre on Relationships. Retrieved January 1, 2004, from http://www.oneplusone.org.uk/Oropesa, R.S., Landale, N.S., & Kenkre, T. (2003). Income allocation in martial and cohabiting unions: the case of mainland Puerto Ricans. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65, 910-926. Pahl, J. (1989). Money and Marriage. London: Macmillan. Pahl, J. (1995). His money, her money: Recent research on financial organisation in marriage. Journal of Economic Psychology, 16, 361-376 Pahl, J. (2005). Individualization in couple finances: who pays for the children? Social Policy and Society,4, 381-392. Pierce, J. L., & Kostova, T., & Dirks, K. T. (2003). The state of psychological ownership: Integrating and extending a century of research. Review of General Psychology, 7, 84-107. Shefrin, H. H. and Thaler, R. H. (1988). The behavioral life-cycle hypothesis. Economic Inquiry, 26, 609-643. Singh, S., & Lindsay, J. (1996). ‘Money in heterosexual relationships’. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Sociology, 32, 55-59. Sonnenberg, S.J. (2008). Household financial organization and discursive practice: Managing money and identity. Journal of Socio-Economics, 37, Sonnenberg, S.J., Burgoyne, C.B., & Routh, D.A. (2006). ‘Income disparity and choice of financial organisation in the household’. Proceedings: 31st IAREP Colloquium “Values and Economy”5-8 July September, Paris, France. Thaler, R.H. (1999). Mental accounting matters. Journal of Behavioral decision making, 12, 183-206. Tichenor, V. J. (1999). Status and income as gendered resources: The case of marital power. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61, 638-650. Vogler, C. (2005). Cohabiting couples: rethinking money in the household at the beginning of the twenty first century. The Sociological Review, 53, 1-29. 39 Vogler, C., Brockmann, M., & Wiggins, R.D. (2008). Managing money in new heterosexual forms of intimate relationships. Journal of Socio-Economics, 37, 552-576. Vogler, C., Brockmann, M., & Wiggins, R.D. (2006). Intimate relationships and changing patterns of money management at the beginning of the twenty-first century. British Journal of Sociology, 57, 455-482. Waite, L. J., & Gallagher, M. (2000). The case for marriage: Why married people are happier, healthier, and better off financially. New York: Doubled 40