Report of the outbreak of diarrhoeal illness in Mountain Bike

advertisement

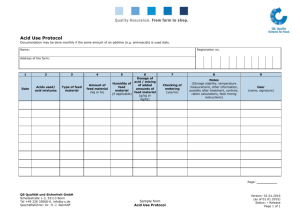

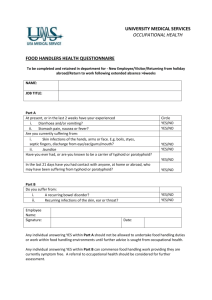

FINAL REPORT: The investigation of an outbreak of diarrhoeal illness in participants of the Builth Wells Mountain Bike Marathon July 2008 Report published … December 2008. Acknowledgements The work of numerous environmental health professionals from Powys County Council and other members of the outbreak control team who made this rapid epidemiological investigation possible is gratefully acknowledged. We would also like to record our thanks to the event organisers and participants for their support which enabled this study to be completed rapidly. Introduction On Thursday 17th July 2008, the ‘feedback’ facility on the National Public Health Service for Wales (NPHS) website received a report of a possible outbreak of diarrhoeal illness. The report was made by a participant of the Builth Wells Merida Bikes Mountain Bike Marathon, which had taken place on the 5th and 6th July. The individual knew of eight people who had become unwell following the event. The same individual also reported that there were many others complaining of similar symptoms on a post-event internet discussion forum. In some cases, the illness was said to have been caused by Campylobacter. Powys County Council Environmental Health Department had also been informed of the cases and began an investigation. Officers spoke to the event organiser, inspected the campsite used for the event and took samples of the mains water supply. Efforts were also made to contact the caterer who had provided the onsite meal service. An Outbreak Control Team (OCT) meeting was convened between the NPHS and Powys County Council Environmental Health Officers (EHOs) on Monday 21st July. At this meeting it was decided that a cohort study should be conducted using an internet based questionnaire housed on the NPHS website. The questionnaire was made available between Thursday 24 th July and Monday 11th August and a preliminary report of the study was published on the NPHS website on 15th August, 2008. This final report, which has been scrutinised by members of the OCT, replaces the latter and presents the recommendations made by the OCT. Background The Mountain Bike (MTB) Marathon The Merida Bikes MTB Marathon is one of a series of six mountain biking events held all over the country1. The event has been held in Builth Wells for a number of years and takes part over two days. On Saturday 5th July, organisers estimate that 130 participants completed either a 40 mile or an 80 mile road ride. On Sunday 6th July, 947 participated in an off road ride of either 25k, 50k, 75k or 90k in length. The proportions participating in each category were estimated to be 10%, 30%, 30% and 30% respectively. Conditions were said to be poor on Sunday following heavy overnight rain which caused the course to become very muddy and led to significant amounts of mud being splashed over participants. The course was also reported to be contaminated with sheep faeces in areas. Feed Stations Feed stations were available on both days. The feed stations provided riders with a choice of drinks and food. The riders could chose from either mains water or an energy drink solution. The latter had been made up from powder with mains water. Both the water and energy drink were stored in large containers and jugged out into the competitors own containers by the event stewards. The food choice was either banana or pre-wrapped Hi 5 energy bars. It is understood that the bars were removed from their wrappers the day before the event and placed in a box for competitors to help themselves. 2 Two feed stations operated on Saturday, one at Cefn Gorwydd and one at Devil’s Staircase near Tregaron. The Cefn Gorwydd feed station was used by riders attempting both distances, acting as the second feed station in the circuit completed by the 80 mile riders, but was the first and only feed station for the 40 mile riders. Three feed stations operated on Sunday. The first, sited at Pant y Llyn, was used by riders attempting all distances. Riders reported to Environmental Health Officers that this area of the hill was heavily contaminated with sheep faeces. The second feed station was sited at Aberedw and was used by participants of the 50k, 75k and 90k events. The third feed-station was sited at Forest Fields and was only used by 75k and 90k participants. Equipment In addition to feed-stations, the bikers also carried their own supplies of food and drink with them. Drinks would either be carried in bottles, usually positioned on the A-frame of their bike, or in rucksack style camel packs which are usually carried on the riders’ backs. Food would most often be carried in the form of low volume, high-energy pre-packed gels or bars. Event facilities Many of the competitors stayed on the event site, camping on the fields of White House Farm. The farm is a licensed Caravan Site and is served with mains water and sewage. The catering facilities were provided by Extreme Hospitality from Nottinghamshire. The catering for the weekend consisted of breakfasts, burgers, cakes etc. as well as a Saturday night ‘Pasta Party’. Campylobacter Campylobacter is one of a group of diseases known as zoonoses, meaning that they move into humans from an animal source2. Campylobacter is a bacterium found in the gastrointestinal tract of birds and mammals3 4. Transmission from animals to humans usually occurs through ingestion of faecally contaminated food or water. The bacterium causes an acute enteritis of varying severity, leading to symptoms of diarrhoea, abdominal pain, fever, malaise and nausea. A third to a half of sufferers also have blood in their stools. Most cases settle within 2-3 days, although symptoms may last up to a week. Rarer complications include reactive arthritis, Guillan-Barré Syndrome and haemolytic uraemic syndrome. The incubation period is usually 2-5 days (average 3), but a range of 1-10 days has been reported. Person to person transmission is uncommon. Methods A cohort study was conducted to test the hypothesis that the outbreak of diarrhoeal illness was caused by drinking from frame mounted drink bottles which had been contaminated with sheep faeces during the race. A case was defined as a participant of the Builth Wells Merida Bikes MTB Marathon event who developed gastrointestinal symptoms within 2 weeks of the event. Information about the organisation of the event, the conditions affecting it and symptoms experienced by participants were gathered by EHOs. This, along with the epidemiology of Campylobacter and the results of a previous similar outbreak5, was used to inform the design of a questionnaire. The 3 questionnaire was circulated amongst members of the OCT and selected NPHS staff for comments. The on-line version was piloted by members of the OCT. Paper and electronic versions of the questionnaire were also produced for those who might have difficulty accessing the on-line version. The EHOs obtained a list of the people who had registered for the event from the organisers. The majority of records were held in an electronic form (Excel Spreadsheet), but paper entry forms were the only record for a proportion. The questionnaire, which was protected by a pass key, went live on Thursday 24th July. Information on the investigation was posted on the NPHS website and a press release issued. E-mails inviting event participants to complete the questionnaire were sent to all those for whom an address was held in an electronic form (i.e. e-mail addresses from the paper entry forms were not entered manually). The e-mail explained the reason for the study, gave a link to the questionnaire and the pass key. The same pass key was used for all competitors. The questionnaire could be completed anonymously. However participants were asked to leave an e-mail address if they were prepared to be contacted for follow up. Responses were automatically entered and stored in a secure database. A reminder e-mail was sent on 30th July to those who had not already responded. An update on progress was posted on the NPHS website on Wednesday 6th August and a final reminder e-mail sent on 7th August. The questionnaire was taken off line at midday on Monday 11th August. Results 664 e-mail invitations were sent in the first mailing, 476 in the second and 400 in the third. 2 paper questionnaires were sent out as well as 1 electronic version. A total of 355 responses were received (52.7% response rate). Of these, 8 did not participate in the event and so 347 were entered into the final analysis. Of those who responded, 29 participated in Saturday’s events and 344 in Sunday’s events. Of these, 2 participated on Saturday only and 318 on Sunday only. 161 individuals (46.5 %) reported that they had been ill. The most frequently reported symptoms were tiredness (159), diarrhoea (151) and abdominal pain (131). Other symptoms included fever (94), nausea (91), vomiting (31) and blood in stools (15). 10 riders reported having stool samples which were positive for Campylobacter. 177 entrants reported that people travelled with them who did not participate in the event. The number of companions varied from 1 to 10. Only 6 were reported to have been ill. This confirms that the outbreak appears to have been limited to event participants. 4 DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS This section gives an epidemiological description of the cohort of participants who completed the on-line questionnaire. Person The cohort comprised 299 males and 45 females (3 sex not recorded). The mean age was 36.8yrs (minimum 17, maximum 63). The mean age of the males was 37.2 years and 33.6 years for the females. Table 1 displays numbers affected and attack rates by sex. Table 1: Attack rates by sex Sex Ill Male 142 Female 17 Not ill 157 28 Attack rate (%) 47.5 37.8 It can be seen that the attack rate in males is higher than in females. However, the difference is not statistically significant (p=0.22). The participants were divided into five age groups. Table 2 details numbers affected and attack rates by age group. Table 2: Attack rates by age group Age group n 15-24 25-34 35-44 45-54 55-64 15 128 140 51 10 Ill Not ill 7 68 62 19 3 8 60 78 32 7 Attack rate (%) 46.7 53.1 44.3 37.2 30.0 It appears that attack rates are higher in younger participants, peaking in the 25-34 year age group. Existing immunity is likely to be a factor in this observation. 5 Place This section describes the distribution of illness amongst the riders who participated in the study in relation to the events they participated in and the feed stations they used. Tables 3 and 4 detail the attack rates for each of the events held over the weekend. Table 3: Attack rates for the events held on Saturday Race n Ill Not ill 40 mile 80 mile 18 11 11 6 7 5 Table 4: Attack rates for the events held on Sunday Race n Ill Not ill 25k 50k 75k 90k 43 192 54 55 16 76 32 37 27 116 22 18 Attack Rate (%) 61.1 54.5 Attack Rate (%) 37.2 39.6 59.3 67.3 The attack rate on Saturday seems to be higher for the 40 mile race. However, the numbers of respondents are small and the difference is unlikely to be statistically significant. On Sunday, there is an increasing gradient of attack rates with increasing distance, up to a maximum of 67.3% in the 90k race. This might suggest a dose response effect, with those completing the longer distances being exposed to the greatest risk. To investigate this observation further, Tables 5 and 6 detail the attack rates based on how long it took the bikers to complete the course. Table 5: Attack rates for time spent completing the course on Saturday Time to n Ill Not ill Attack Rate complete (%) <2hrs 2 0 2 0.0 2 - 2.5hrs 3 2 1 66.7 2.5 - 3hrs 8 6 2 75.0 3 – 3.5hrs 4 3 1 75.0 3.5 – 4hrs 1 0 1 0.0 4 – 4.5hrs 2 1 1 50.0 4.5 – 5hrs 0 0 0 0.0 5 – 5.5hrs 7 3 4 42.9 5.5 – 6hrs 6 3 3 50.0 6 – 6.5hrs 1 0 1 0.0 6.5 – 7hrs 0 0 0 0.0 >7hrs 1 0 1 0.0 6 Table 6: Attack rates for time spent completing the course on Sunday Time to n Ill Not ill Attack Rate complete (%) <2hrs 2 0 2 0.0 2 - 2.5hrs 11 4 7 36.4 2.5 - 3hrs 13 6 7 46.2 3 – 3.5hrs 17 9 8 52.9 3.5 – 4hrs 20 14 6 70.0 4 – 4.5hrs 49 29 20 59.2 4.5 – 5hrs 51 24 28 46.2 5 – 5.5hrs 54 21 34 38.2 5.5 – 6hrs 45 13 32 28.9 6 – 6.5hrs 36 17 19 47.2 6.5 – 7hrs 22 11 11 50.0 >7hrs 20 12 8 60.0 There is no clear gradient with increasing time to compete the course on either day, which suggests that there is not a simple dose response association. It is possible therefore that the increased risk is associated with exposure to a particular area. We therefore looked at attack rates by feed station. Tables 7 and 8 detail attack rates by feed stations used on both days. Table 7: Attack rates by feed stations used on Saturday Feed station n Ill Not ill 1 2 1+2 Neither Can’t remember 9 4 10 17 4 6 2 6 10 1 3 2 4 6 3 Table 8: Attack rates by feed stations used on Sunday Feed station n Ill Not ill 1 2 3 1+2 2+3 1,2+3 None Can’t remember 42 48 10 111 30 59 24 11 18 29 4 45 20 30 7 5 24 19 6 66 10 30 18 7 Attack Rate (%) 66.7 50.0 60.0 62.5 25.0 Attack Rate (%) 42.9 60.4 40.0 40.5 66.7 50.0 28.0 41.7 Attack rates are very similar for all the feed stations used on Saturday. It must be remembered that in our sample, most of the bikers who took part on Saturday also competed on Sunday. It is possible therefore that any illness experienced may have been a result of exposures on either day. 7 In table 8 it can be seen that the lowest attack rate was seen for those who did not use any of the feed stations (29.2%). The highest attack rates are seen for feed stations 2 and 3. This observation will be confounded by the fact that these two stations are used only by those on the longer races. Time Chart 1 presents the timing of onset of symptoms in our sample population. Day 0 is Saturday 5th July. It can be seen that there is a clear peak in cases reported between days 2 and 5. The maximum number of cases was reported on day 3 (Tuesday 8th July). The final case was reported some 15 days after the event on Sunday 20th July. Chart 1 MTB Marathon Outbreak Curve 60 Number of incident cases 50 40 30 20 10 0 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Days after event This profile is characteristic of a point source outbreak. The timing of cases is consistent with Campylobacter infection. 8 ANALYTICAL STUDY To investigate the observational findings further, a cohort study was conducted in order to produce relative risks of illness for a variety of exposures. For the purposes of the study, the significance level was set at 95%, meaning that p values less than 0.05 would be accepted as being significant. Table 9 presents the results of an analysis of the data for all participants over both of the days. Significant results are highlighted. Table 9: Relative risks of various exposures for all participants over both days Exposure Exposed Not Exposed RR 95% p CI Ill Not ill Ill Not Ill Water from 72 72 88 113 1.14 0.910.25 station 1.43 Energy Drink 127 126 33 59 1.40 1.040.018 from station 1.89 Energy bar 97 86 63 99 1.36 1.080.009 from station 1.73 Banana from 112 134 48 51 0.94 0.740.62 station 1.20 Drink from 74 70 86 115 1.20 0.960.11 own bottle 1.50 Drink from 140 156 20 29 1.16 0.810.44 Camel pack 1.66 Other 45 32 114 152 1.36 1.070.016 food/drink 1.72 during event Ingested mud 124 103 36 82 1.79 1.33- <0.0001 2.41 Stayed at 88 105 72 78 0.95 0.760.66 camp 1.19 Drank camp 54 58 84 93 1.02 0.790.90 water 1.30 Ate food from 96 110 42 42 0.93 0.720.59 camp 1.21 Attended 67 79 92 105 0.98 0.780.88 pasta party 1.24 RR= Relative Risk AR=Population Attributable Risk Importantly, no increased risk of illness was associated with residence at the camp site, eating from the food outlet or drinking the mains water. Additionally, there was no increased risk associated with attendance at the Saturday night pasta party. However, significantly increased risks are associated with factors associated with the event itself. The greatest risk is associated with the inadvertent ingestion of mud (Relative Risk [RR] 1.79, p=<0.0001, Attributable Risk [AR] 34.2%). Drinking an energy drink from the food station was the next highest risk (RR= 1.40, p=0.018, AR=22.7%), followed by eating an energy bar from the feed station (RR=1.36, p=0.009, AR=16.18%) and eating other food (RR=1.36, p=0.016, AR=7.5). Drinking from a frame mounted bottle also 9 AR (%) 5.6 22.7 16.1 (4.3) 7.7 12.0 7.5 34.2 (2.8) 0.60 (4.8) (0.7) presented a raised risk (RR=1.20) but this did not achieve significance (p=0.11, AR=7.7). Other in-event factors (drinking from a camel pack, drinking water from the feed station) did not present a statistically significant increased risk. Interestingly eating a banana was associated with a reduced risk (RR=0.94), although this was not significant (p=0.62). The above analysis was repeated using the Saturday and Sunday competitors separately, but it did not affect the results or the conclusions and so has not been included. Finally, the statistically significant factors were put into a logistic regression model with the risk of being ill. This determines whether there is any interaction between the factors. Table 10 displays the results. Table 10: Logistic regression of significant factors Risk factor Odds Ratio Ingestion of mud 2.72 p <0.001 Energy Drink from station Bar from station 1.70 0.058 1.44 0.138 Other food/drink during event 2.16 0.006 It can be seen that eating an energy bar and drinking energy drink from the food stations no longer achieve significance, although the latter only just fails to do so. However, ingestion of mud and consumption of other food or drink remain highly significant. It appears therefore, that these two factors act independently of one another. Overall, inadvertent ingestion of mud presents the greatest risk. Conclusions It is clear that the risk factors associated with illness in this outbreak occurred during the race and were confined to race participants. No increased risk was associated with residence at the campsite, drinking the water at the campsite, eating at the food outlet or attending the pasta party. The most statistically significant risk was the inadvertent ingestion of mud. Drinking energy drinks and eating energy bars from the feed stations was also associated with a significantly increased risk of illness, as was the consumption of other food and drink during the event. This picture is consistent with the widespread contamination of hands and utensils with mud providing a vehicle for infection. Although microbiological confirmation has not been received for the majority of participants, the results of the study are consistent with a point source Campylobacter outbreak. The nature of this sport means that riding through muddy, agricultural land is unavoidable. The risk of infection from zoonotic organisms such as Campylobacter will therefore always be present. Clearly the weather conditions on the day of this event compounded the problem by making contamination by mud inevitable. 10 Recommendations Whilst it will be impossible to eliminate completely, the following actions should be considered in order to minimise the risk of contracting Campylobacter and other zoonotic infections in future mountain bike events. Recommendations to participants 1. The use of obviously soiled drink and food containers should be avoided. 2. Pre-packaged food should be eaten out of the wrapper. 3. Where possible, hands and utensils should be washed before consuming food and drink. Recommendations to event organisers 1. No open food should be served. 2. To avoid the risk of contamination, drinks produced in large volumes for consumption by participants should be dispensed using a method which does not require the repeated immersion of utensils. 3. Provision of facilities to wash hands with clean, running water should be considered. 4. Provision of facilities to wash drinks bottles with clean, running water should be considered. 5. Wherever possible, courses should be re-routed to avoid areas which are heavily contaminated with animal faeces. 6. Mountain bikers should be alerted to the potential risk of acquiring zoonotic illnesses from participation in events which cross land used by agricultural and other animals. The information would be of particular relevance to riders who are vulnerable to infection as a result of illness or medical treatments. Bibliography 1 Welcome to the 2008 season of the Merida Bikes MTB Marathon Series accessed at http://www.mtb-marathon.co.uk/ last accessed 12/08/08. 2 NPHS Infections from Animals accessed at http://www.wales.nhs.uk/sites3/page.cfm?orgid=457&pid=25225 last accessed 22/09/08 3 J Hawker, N Begg, I Blair, R Reintjes, J. Weinberg (2005) Communicable Disease Control Handbook Blackwell Publishing: Oxford 4 D L Haymann (Ed) (2004) Control of Communicable Diseases Manual, American PublicHealth Association: Washington 5 Infectious Disease News. Emerging Diseases: Campylobacter outbreak among mountain bikers linked to mud. Accessed at http://www.infectiousdiseasenews.com/200805/outbreak.asp Last accessed 13/8/08 11