criticisms of Rawls

advertisement

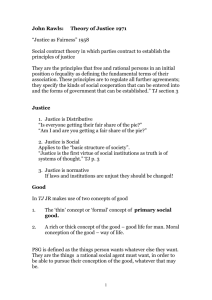

Cohen’s Objection A. The Problem of inequality-generating incentives. 1. Lax interpretation of Diff principle permits workers to be self-interested in their market behaviour. 2. `Strict interpretation require that workers adopt an egalitarian ethos in their market behaviour. Example: Career Choices 3. The strict principle prohibits a wider range of inequalities than the lax principle. 4. Rawls’s arguments favour the strict principle. 5. Rawls’s conclusions about the degree of permissible inequality rely on the lax principle. B. Basic Structure Argument: Reply to Cohen 1. 2. 3. Rawls states that the difference principle applies to the basic structure. an egalitarian ethos is not part of the basic structure Rawls’s arguments do not favour the strict principle. A Dilemma for B. Basic structure = either a) legally enforced rule or b) profoundly influential activities and attitudes If a) the basic structure restriction is i. arbitrary and ii. implausible. Example – it permits a sexist domestic ethos. If b) one cannot claim that an egalitarian ethos is not part of the basic structure. 1 Rawls argues that teleological theories that argue that there is some end that human beings should strive to realise pursue or even maximise gets things the wrong way round. They are “radically misconceived” since they relate the right and the good in the wrong way. “We should not attempt to give form to our lives by first looking to the good independently defined [GF e.g. the pursuit of happiness, pleasure or philosophy]. It is not our aims that primarily reveal our nature, but rather the principles that we would acknowledge to govern the background conditions under which these aims are to be formed and the manner in which they are to be pursued. For the self is prior to the ends which are affirmed by it.” TJ 560. Rawls maintains that individual selves, both in the original position and in society itself, reserve the right to refine and revise their life projects even their deepest ends and attachments. B. Sandel’s Objections Rawls’s stipulation that principles of justice be chosen under a veil of ignorance is supposed to model conditions of fairness and equality by eliminating any individual or group-specific information by which they can calculate their own advantage and tailor their distributive principles accordingly. According to Sandel, this device has three deleterious effects: First, it deprives the choosers of any individuating features and generic differences. Second, it reduces all participants to one and the same abstract rational person, and hence it cannot tell us anything interesting about how a plurality of human beings can found a political association. 2 Third, and worst of all, the single self behind the veil of ignorance is “incapable of constitutive attachments” and devoid of “constitutive ends”. Sandel (bizarrely) calls this self “unencumbered” and objects that it is “wholly without character, without moral depth.”) Sandel (1982: 179).”1 Sandel’s criticisms were enormously influential. One legacy of his influence is that the phrase he uses to describe his target “the unencumbered self” is still part of the lingua franca of political philosophy, even though it makes little sense in ordinary English. 2 N.B. J. L. Austin’s warning: “One can’t abuse ordinary language without paying for it.” Austin (1962: 15). 1. The Unencumbered Self. Wrong conception of the person 2. Priority of the Right 3. The Unencumbered self is “wholly without character, without moral depth”. 4. Wrong picture of society – no “constitutive attachments” – no conception of belonging or membership in a community. 1. Rawl’s liberalism gives a wrong picture of the self. This critique, as Rawls points out, assigns ontological significance to the choosers in the original position, who are models, rather than to the real selves and citizens in the political community whom they model, which indicates that Sandel has mistaken the status of the original position as a device of representation. “The veil of ignorance…has no specific metaphysical implications concerning the nature of the self” Rawls (2005: 27). Does the original position contain an implicit social ontology, a picture of what society is or is supposed to be? 1 This critique, as Rawls points out, assigns ontological significance to the choosers in the original position, who are models, rather than to the real selves and citizens in the political community whom they model, which indicates that Sandel has mistaken the status of the original position as a device of representation. “The veil of ignorance…has no specific metaphysical implications concerning the nature of the self” Rawls (2005: 27). 2 What is so odd about Sandel’s phrase is that, in direct contrast to normal English usage, he gives the term ‘encumbered’ an affirmative sense, and the term ‘unencumbered’ a pejorative one. In English, as normally spoken, it is a bad thing to be ‘encumbered’, i.e. burdened, loaded down, hampered, hindered, and made to suffer. Thus most people like to see their relations to their nearest and dearest, to their parents and children for example and to their community and culture as more than just ‘encumbrances’ even if they are not the ones we ideally would have chosen. Conversely, in usual parlance, it is a good thing not to be encumbered (burdened etc.) and therefore also good to be ‘unencumbered’. This reminds me of J. L. Austin’s warning: “One can’t abuse ordinary language without paying for it.” Austin (1962: 15). 3 If not, Rawls might still be in trouble. Rational choosers in the oirignal position are different from the real citizens they are supposed to model. Why should persons outside the original position agree to abide by the principles they chose within it, behind the veil of ignorance, if choosers of the priniciples are not the same as the agents who must live by them. 2. The unencumbered Self implies the Priority of the Right According to Sandel, the picture of unencumbered self’ prior, and at a distance to, its aims or ends, “rules out the possibility of …constitutive ends”. “For the unencumbered self, what matters above all, what is most essential to our personhood are not the ends we choose but our capacity to choose them.” “Only if the self is prior to its ends can the right be prior to the good. Only if my identity is never tied to the aims and interests I may have at any moment can I think of myself as a free and independent agent.” The self is a kind of radically unattached, individual chooser, with no substance. The Unencumbered self is thus “wholly without character, without moral depth”. 2.1 Kymlicka’s qualified defence of Rawls. Rawls’ claim that “the self is prior to the ends which are affirmed by it” Rawls (1973: 560). This can be interpreted as meaning either a) in a liberal society no life-project or attachment or end, however deep, is beyond re-examination and revision, or b) as the normative claim that each person should be free to interpret and re-interpret his or her own life as he or she sees fit compatibly with everyone else’s similar freedom. See Rawls (1973: 560). When push came to shove Sandel was reluctant to deny either the empirical or the normative claim. Kymlicka, (1989: 55) If what Sandel meant by the rejoinder that selves are, pace Rawls, “encumbered” was only that “some relative fixity of character appears essential to prevent the lapse into arbitrariness” See Sandel (1982: 180). Rawls could perfectly well agree. 4 They can, for example, both agree that at any one time some of a person’s ends are revisable and others not, whilst allowing that there is no fixity about which ends are fixed and which revisable. 2.2 The encumbered self may be constituted by antecedent attachments and substantive ends but these are local. They give rise to one of the problems to which a well-ordered political community is the answer. MacIntyre: After Virtue ‘…we all approach our own circumstances as the bearers of a particular social identity. I am sonmeone’s son or daughter, someone else’s cousin or uncle.: I am a citizen of this or that city, a member of this or that guild or profession; I belong to this clan, that tribe, this nation.’ Insofar as this is true, we are not shaped (constituted is just too strong!) or influenced by our membership in a political community. It is family, locality, and the immediate environment that shape our ends. (We do not live in Rousseau’s Geneva or his idealised version of Sparta, or in Aristotle’s Athens.) These local factors, will determine people’s substantive ends and values differently. People with different ends and values may well and often do come into conflict or disagreement with one another. A modern mass large-scale political community must unite all kinds of different people, with different substantive ends, from different family and local cultures. Rawlsian liberalism accepts pluralism and diversity as a fact, and then proposes an answer – namely that individuals abstract from their substantive ends and conceptions the good that bring them into conflict and generate disagreement, and unite around priniciples that are based soley on the values that they have in common. Communitarians overestimate the shaping and socialising effect of membership in a political community, they mistakenly assume that a political community will have a largely homogenous set of substantive values, and have no answer to the problem of pluralism and diversity. Communitarian answer will either be – conflict, tyranny of the majority over the minority, or large-scale social engineering. 3. Wrong picture of society – no “constitutive attachments” – no conception of belonging or membership in a community. Sandel and MacIntyre appear to make two separate sets of objections. A Rawls (and liberalism) has the wrong social ontology – wrong picture of the self and its relation to society. 5 1. Rawls and liberals in general (including Kant!) give the wrong picture of the self and society. The liberal self has no “constitutive attachments” it is a ‘ghost’ or a ‘cipher’. 2. Society and membership in a political community has no pre-eminent or inherent value. Wrong conception of belonging - Rawlsian selves have a purely instrumental or prudential relation to the political community. Community is evacuated of meaning – because all selves are purged of anything specific and particular in the OP, and are thus made the same by a device of the philosopher. Of course they agree on the principles because, having been made the same, it is just as if there is only one of them.) B. Liberalism (and liberal ideas) has given rise to a wrong social ontology in a different sense: it has produced a bad society, fragmented communities, destroyed the shared understandings and formative attachments of communities and emptied our lives of shared meaning. Sandel deplores what he calls “the shift in our practices and institutions, from a public philosophy of common purposes to one of fair procedures, from a politics of the good to a politics of right, from the national republic to the procedural republic.” Communitarinaism and Liberalism p. 27 (Avinieri and de-Shalit) He blames Rawls conception of liberalism as a kind of simple reflection of this wretched state of man’s and women’s alienation from themselves sand their community A. and B. when conceived as criticisms of Rawls pull in entirely opposite directions. If A. is true, then surely B. cannot be. On the one hand Sandel’s claim seems to be that the picture of the “unencumbered self” contained in the original position is false, and that the concomitant liberal picture of society as a “procedural republic”, i.e. as an aggregate of lone, rational, unencumbered selves who value choice above all things, is also false.3 On the other hand Sandel argues that the Rawlsian liberal picture of both self and society is true, more is the pity. Here he makes the normative claim that, due in part to the nefarious influence of liberal ideas and political theories, self and society have become what liberalism says they are. Liberalism (among other things) has led to the emergence of an atomised society of self-interested rational choosers with no orientation to the common good, and is to this extent responsible 3 Sandel (1982) passim; and (1984). The contention here is that Rawlsian liberalism paints the wrong picture of self and society. 6 for the atrophy of political association and for the increase in feelings of alienation and disempowerment among citizens.4 It is as though the ‘unencumbered self’ presupposed by the liberal ethic had begun to come true.” Sandel (1984: 90-96) Does Rawls give an accurate picture of a ‘wrong’ ‘false’ or bad liberal society (bad because emptied of shared social meaning and populated by beings alienated from themselves and each other)? Or does he give an inaccurate report of a society that has not been so damaged and emptied of meaning and in which people are actually shaped by communities, constitutive ends and value their membership in communities and so forth. This problem arises because Sandel attempts to get a one-size fits all critique of liberalism (as an historical force) and as Rawlsian theory. And its not clear that when he is railing against liberalism he’s not actually railing against modernisation and social forces, and a tide of history that cannot be turned back, certainly not by a change of philosophy. C. What is the actual substantive difference between communitarians and liberals. How do communitarians theorize about politics and conceive of the political community? Almost nothing. What are the real political and social issues between the liberal individualist and the communitarian? A) Rawls is making normative claims: that each person should be free to interpret and re-interprets his or her own life as he or she sees fit; B) Political claim that establishing the framework of a just well-ordered society is the central task of politics and political theory. B) Philosophical claim: that the principles of justice provides a framework within which this freedom is best assured. It turns out that there are almost no differences. Communitarians, we have seen, when pushed don’t deny A). 4 “It is as though the ‘unencumbered self’ presupposed by the liberal ethic had begun to come true.” Sandel (1984: 90-96) Of course Rawls denies this claim. He maintains that the citizens in a liberal and just society do (or would) have an orientation to the common good, once this is reinterpreted as an orientation to political values Rawls (2005: 201-7). 7 They do not disagree with B). (as Nozick and the libertarians do) about the idea that the advantages of social cooperation should be fairly allocated, and hence that wealth should be redistributed to the extent that inequalities must at least indirectly benefit the least well off. They deny 3. It turns out that they bring mainly philosophical objections to the argument by which Rawls attempts to establish his principles of justice. Perhaps to the principles themselves. But they don’t object to the vision of liberal society he is advancing. They don’t even disagree about substantive points – say about whether pornography is morally abhorrent because degrading for women. They disagree about the grounds on which it should be prohibited – see Kymlicka. 8