Competency Assessment - An Art or Science – A Case for the

advertisement

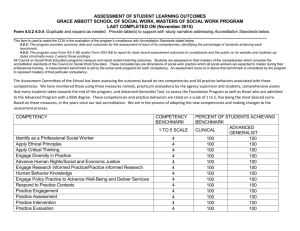

Header Space reserved for Publication COMPETENCY ASSESSMENT - AN ART OR SCIENCE – A CASE FOR APPLYING THE LANGUAGE PROCESSING METHOD J Ravikant 1 and Dr. Mahesh Deshmukh 2 1 2 Associate Vice President – Corporate TQM and People Development SRF Limited, Gurgaon, India email: jravikant@srf.com Managing Director, Maruma Consultancy Pvt. Ltd., Navi Mumbai- 400706, India email: maruma@rediffmail.com ABSTRACT Psychometric tools have been shown to be amongst the most powerful aids in the crucial problem of selecting and developing people to create a high capability organisation. Competency assessment, using a set of psychometric and other tools, is carried out through an assessment or development centre, and establishes the datum for capability building in an organisation. This assessment methodology is now standardised to define and evaluate job relevant competencies for different levels within an organisation. However, determination of proficiency of an individual in any competency continues to be a challenge not only for HR professionals but also for line managers. An attempt was made to explore the parallels between the competency based assessments and the standardization of processes as advocated by a quality philosophy. Competencies are generic, and a skilful evaluation of these for development and assessment purposes is critical in identifying and building the capabilities of an individual. Standard HR practices have built competency assessment through the training of assessors. Evaluation consists of methods like in-basket exercise, personality questionnaire, competency interviewing, role play and group exercise. The entire process being language based, has large inherent variations both within and between appraisers. This variation exists both at the level of data capture (in this case language data – what an individual says) and in further processing, abstraction and evaluation of proficiency level. The evaluation method is consistent with the TQM methodology of meticulous observation, data recording, classification, integration and evaluation. This paper puts forward an integrative approach using language processing methods as advocated by S Hayakawa and later modified by Prof. Shoji Shiba with the current approaches. The key improvement is to systematize the collection of verbal data and the use of abstraction ladder in the synthesis of language data. This integrative approach is a unique feature in the entire assessment process, including the training of assessors and interviewers. This has potential for vastly improving the quality of competence based assessments and making talent management processes more effective in any organisation Keywords: Competency Assessment, Language processing, Abstraction ladder INTRODUCTION In an ever changing world, all individuals and organisations alike want to raise their capabilities across dimensions – mastery over self (personal mastery, or “I”), mastery over interdependence (interpersonal skills or “we”) and knowledge and domain skills.(“It”).This can be viewed as a triad of people capability (I, We, It model - Ken Wilber). Whilst knowledge and skills in technical or functional domains can be more readily measured using functional scales, the ability to perform on the job is a much sought out indicator. What is even more arduous and tricky is the prediction of how well a person will perform in a role, which is a function of not only current performance but future potential as well. With human resource increasingly becoming the most fundamental differentiating factor for success in any organisation, the need to make a sound prediction is paramount not only for line managers but for the HR fraternity as well. Many systems have evolved to address this need of potential appraisal. At the core of potential appraisal or prediction is the question of what to look for – a set of indicators which can best determine an individual’s performance in the future. Competency models seem to have addressed this need for what to look for. The models offer a level of sophistication in how we look at success factors as well as robust criteria against which we can measure one’s performance. This modelling effort has been well supported by evaluation methodologies as advocated by assessment/development centres. This paper examines the notion of competency, issues in evaluation methodologies and how we can apply the concept of ladder of abstraction in order to arrive at a more rigorous and objective evaluation of competencies. Definition of competency There are several definitions of competencies offered by researchers and practitioners “A written description of measurable work habits and personal skills used to achieve work objectives”. (Green, 1999) “A job competency may be a motive, trait, skill, aspect of one’s self image or social role, or a body of knowledge”.(Boyatzis 1982) We offer a definition of Athey and Orth (1999) modified by Deshmukh (2005, 2008) “A set of observable performance dimensions/ behaviours, including individual knowledge, skills, attitudes, and personality as well as collective team, process, and organisational capabilities, that are linked to high performance, differentiate a consistently high performer from a low performer, and provide the organisation with sustainable competitive advantage”. (italics by Deshmukh 2005) Page 1 of 9 Header Space reserved for Publication An individual’s success at the workplace is linked to how well one sharpens one’s competencies and demonstrates them in action. Behavior that produces successful results at the workplace decide capability. It is interesting to note that competency based systems are practiced in order to differentiate high performers from the low performers but this was not a part of the formal definitions in the literature. Hence the modification to Athey and Orth’s definition to include this notion of differentiation.. Competencies based systems are becoming popular, based on four main benefits that they promise: A common language for describing work requirements A framework for integrating people systems A guide for development or performance measurement or improvement A strategic linkage to business strategies Competencies have been categorized differently by various researchers - threshold and differentiating (Spencer & Spencer, 1993) individual, organisational (Green, 1999), technical (Miyazaki, 1999), and core competencies (Prahalad and Hamel, 1990). Threshold and differentiating competencies are briefly examined in order to understand the issues around objective evaluation. Threshold Competencies: These are the essential characteristics (usually knowledge or basic skills, such as the ability to read) that everyone in a job needs to be minimally effective but that do not deliver outstanding performance. A threshold competency for an operator is the knowledge about operating the machine or the ability to read the drawings. Differentiating Competencies: These factors distinguish superior from the average performers. For example, achievement orientation expressed in a person’s setting goals higher than those required by the organization, is a competency that differentiates superior from average salespeople. Proponents of individual/organizational competencies, and threshold/differentiating competencies agree that competencies are behavioural in nature and that they should be observable in order to be measurable. This nomenclature is similar to the Iceberg model proposed by Spencer & Spencer (1993). Skills Visible Skill Knowledge Hidden Self-Concept Trait Motive Self-Concept Trait Motive Attitudes Values Knowledge Figure 1- Iceberg Model (Source: Spencer & Spencer, 1993) Core Competencies – are most difficult to evaluate and develop Surface Competencies – are easy to evaluate and develop Figure 2 – Central and Surface Competencies (Source: Spencer & Spencer, 1993 As illustrated in Figure 1 and 2, knowledge and skill competencies are relatively visible, surface characteristics of people. Self-Concept, trait, and motive competencies are more hidden, deeper and central to personality. Surface knowledge and skill competencies are relatively easy to develop, for example, through training. Core motive and trait competencies at the base of the iceberg are more difficult to assess and develop; it is most cost-effective to select for these characteristics than for surface traits. Self-concept competencies lie somewhere inbetween core competencies and traits. In typical managerial jobs which are complex, competencies are relatively more important in predicting superior performance than are task-related skills, intelligence, or credentials. This is due to “restriction range effects”. Restriction of range occurs when one, or sometimes both, variables correlated contain only restricted variance. For instance applicants could be selected on the basis of high cutoff scores on an ability test, who are later followed up in a validation study. This particular case does not provide any data on low-test performers. Thus, one is restricting the scores to one end of the continuum. Competency model by its very nature includes skills, intelligence and knowledge and considers high and low performers in its development and measurement. This helps in minimizing the restriction range effects. In an organizational context, competencies are directly linked to the concept of Knowledge, Skills and Attitudes (KSAs) – see Figure 3. In this paper, we will deal only with generic competencies which are behavioural in nature, as distinct from technical competencies, which are domain specific and relate to the knowledge and skills. Domain related competencies are also realised through the generic competencies, and the evaluation of these is outside the scope of this paper Page 2 of 9 Header Space reserved for Publication Figure 3 – Competencies and linkage to KSA ASSESSING COMPETENCIES Competency Frameworks Each role has a set of competencies that determine what constitutes high performance. These are also distinct by level, eg, the set of competencies required of a first level manager will be very different from those of a plant head or a general management position. Thus, each organisation must determine a matrix of competencies for each job level in the organisation. At junior levels in the hierarchy, competencies would typically include communication, planning and organising, team working etc. Competencies at senior levels demand higher levels of cognitive complexity, eg, persuasive communication, leadership, analytical decision making etc. Typically, a competency matrix of a mid level manager upwards would include eight to ten competencies for assessing their potential. Each competency is further broken down into a set of positive and negative descriptors, which typify the behaviours related to that set. Evaluation Systems and Challenges Though determination of competencies is a challenge, their objective measurement poses a greater challenge. All competencies are observable behaviours, and we only have access to these observables to evaluate competencies. In addition, any evaluation of people is based almost entirely on language data, with interpretation of numerical tests like IQ being a base criterion. Observations are prone to perceptual biases of assessors. Inherent to any decision making process such as assessment is observation, selection of facts, formulation of inferences and arriving at judgements, each step of which is based on perceptual biases of assessors, their mental models and experiences (Figure 4). Figure 4 – Evaluation and Decision making processes (Adapted from “Four Practical Revolutions in Management” - Shiba – 1993) Any objective methodology for evaluation should in the least be able to account for these perceptual differences, and reduce their impact. Assessment or development centre approaches have been developed to partially alleviate this problem, by using multiple assessors thereby reducing individual biases. Assessments use a basket of tools to reduce the risk of basing the entire assessment on just one or two opportunities for observation. A typical competency framework, together with the multi-tool assessment system is shown in Page 3 of 9 Header Space reserved for Publication Table 1, in which each competency is assessed more than once, with different assessors observing the candidate across the basket of exercises. White spaces in the matrix indicate a specific competency assessed by each exercise on a 1-5 rating scale. However, the system introduces between-appraiser variation as well, which is addressed through an “integration” process of consensus building between appraisers. At the core of the assessment lies the ability of each assessor or appraiser to not only capture language data, but also process it meaningfully in a similar manner, in order to reduce both within-appraiser as well as between-appraiser variations. It is here that we propose the utility and training of assessors/appraisers in leveraging the language processing methodology to minimize the variations and enhance inter-rater reliability, a sought after statistical rigour in qualitative research. Table 1– Sample Assessment Matrix (Job Level X) Exercise Competency Role Play Inbox Group Exercise Presentation Interview Ability Test Personality Questionnaire Customer Orientation Openness to Learning Quality and Improvement Orientation Strategic Thinking Networking Team/Interpersonal Skills Communication Skills People Development Planning and Implementation Analysis and Problem Solving Competency Matrix Each competency is further detailed into a set of positive as well as negative indicators/criteria: key sentences which describe specific behaviours or actions that the individual demonstrates. These are at a more concrete level than the label of the competencies. eg, “Planning and Organizing : Comes up with alternatives, considers key options and arrives at key deliverables. Let us examine this through an illustration. Table 2 illustrates a typical competency of “Problem Solving and Analysis”. Table 2 – Competency – Analysis and Problem Solving Definition: Produces a range of solutions to problems based on perceived relationships, patterns, and cause and effect. Negative Indicators (criteria) Positive Indicators (criteria) Needs help when faced with problems Grasps problems quickly in their totality Makes ineffective responses to problem issues Uses sound judgment to arrive at appropriate solutions to solve the problems Is unable to identify gaps in the plans and foresees areas of concern in planning and execution Is able to identify gaps in the plans and foresee areas of concern in planning and execution Is unable to differentiate the key elements from the trivial Is able to differentiate the key elements from the trivial Is unable to get to the root of the problem Addresses the symptoms rather than the cause of the Produces workable solutions that meet the demands of the situation problem Gets to the root of issue – does not take things at face value Evaluating Competencies through “ORCE” – rotating the PDCA cycle In a typical assessment, evaluation is based on a robust matrix of scientifically designed exercises and competencies (Table 1 shows a typical matrix). A typical basket of exercises consists of methods like in-box exercise, personality questionnaire, competency interviewing, role play, aptitude test and group exercise and presentation. Each participant goes through all designated exercises and there are trained observers or assessors who observe the behaviours of each participant, keep verbatim notes and evaluate the participant based on the factual data. The factual data is put through a series of iterations to move it to higher levels of abstraction and compare the facts with the criteria and definitions to arrive at a proficiency rating. The rating is done on a numerical scale say 1 to 5, where level 1 Page 4 of 9 Header Space reserved for Publication indicates absence of data or the lowest level of demonstration of positive behaviours and level 5 indicates that the participant has demonstrated all positive behaviours that are described by the criteria and the definition of the competency. The entire process being language based has large inherent variations both within and between appraisers. This variation exists both at the level of data capture (language data – what an individual says) and in further processing, abstraction and evaluation of proficiency level. The assessors are trained in the process of ORCE (see below), in order to arrive at objective evaluation of the competency. Evaluation is done using the 4-step ORCE process: Observation Recording Classifying Evaluation Observe what the individual does or shares, e.g., when someone says “I had plenty of satisfaction in the job because I was able to see results I had achieved myself”, observe in terms of the following: Behaviour: Expression of satisfaction and excitement with the achievement of results Competency exhibited: Achievement orientation Recording: While evaluating an individual, it is very important to record evidence and circumstances which made an individual to behave in a positive or negative manner. The participant or assessee’s statement is recorded verbatim, together with the tone and emotions. Classifying: Once a particular behaviour is observed and recorded, it is essential to classify it under a set of competency and its positive & negative indicators. Evaluation: Finally identify the level of competency rating based on the presence or absence of a dominant /preferred behavior at workplace. Absence of a behavior required for exhibiting a competency should be explored further for evaluation The above method is consistent with the PDCA approach of meticulous observation and recording of the raw voice and facts, as they are told. Classification is akin to stratification and organising into buckets, in this case, sifting the data into different competencies. Raw voices, includes images tone and emotions and are also classified. Evaluation is akin to analysis, interpretation of the raw data, to yield processed information on the extent to which the listed behaviours have been exhibited by the candidate in a particular exercise. Each exercise yields processed information on more than once competency. The integration exercise is akin to the CA cycle, validating the data across exercises, checking for consistency, reaching agreement across appraisers and making the final adjustments to the scores against each competency. . There seem to be three theoretical models/methods that seem to contribute to a better processing of information especially that we observe and hear during competency assessment process: abstraction (Hayakawa, 1939; Piaget, 1932; and Shiba, 1993), inductive reasoning and analysis-by-synthesis model of cognitive psychology domain (Best, 1999; Halle & Stevens, 1964; and Liberman, 1967). This paper focuses primarily on the abstraction processes. The other method is useful in building missing factual data that can be further used for abstraction; hence this will not be addressed here. INTEGRATION WITH THE LANGUAGE PROCESSING METHOD Semantic methods are the basis for discovering the underlying facts from language data. Semantics is the scientific study of the relation between language and reality. The paper discusses very briefly two theoretical perspectives offered by Piaget and Hayakawa. Noted psychologist, Piaget (1932), studied the way people think from birth to adulthood. He found that humans can achieve four separate stages of reasoning ability or ways to deal with words and their varying degrees of abstraction. The first two do not concern us, as they concern sensory motor development, which all normal humans attain. The third and fourth stages are the ones that we must attend to. The third one Concrete Operational stage, gives humans the ability to deal with dualities. This phase gives us the ability to understand the world according to our own experiences, the way we make decisions and how we make sense of things around us. This is particularly useful in training the assessors in order to enhance objectivity in the rating process. The fourth stage is of Formal Operations. People of Formal Operations hold diverse opinions about the same issues; for example, they may believe that building nuclear armaments is wrong, but they also believe, that a hostile regional environment is an underlying condition for the decision of building nuclear capability. To Concrete Operations person, a Formal Operator seems to sit on a fence about every issue. This distinction is again useful during the stage of integration as it will help assessors appreciate the difference of opinions and evaluate more objectively. Now here's the kicker: Piaget suggested that approximately only 20% of the population ever achieves this stage. Scientists after him suggest that the figure is probably closer to 15%. Think of the implications: any audience is comprised of 80% concrete and 20% formal thinkers. Thus, we turn to our purpose: how to reach all members. That's where Hayakawa's comes in for his rhetorical abstraction ladder. What this ladder tells us is that any good communication includes all levels of abstraction, level one specifically. S.I. Hayakawa, in 1939, conceptualised and proposed a method of classifying fact language into different levels of “abstraction”, from the level of molecular phenomena to observable facts and further generalisations and concepts, which are many steps removed from real facts. This is called the ladder of “abstraction”. Page 5 of 9 Header Space reserved for Publication Ladder of Abstraction The uniqueness of the abstraction ladder is in delineating observable facts from what we say about them or infer from them. For instance, when a person exclaims, “I can’t stand this room”, it can mean a number of things from his not liking the furnishings or the décor of the room, or the available open space, or smells present in the room. It is very difficult to conclude from this statement (an emotional statement as distinct from a fact statement) that the real issue is that room is hotter than what the person wants it to be. Further examination or probing would reveal that the room temperature is currently at 26 degrees celsius against the set temperature of 23 degrees celsius., which is the observable fact or the event (adapted from Shiba). The expression “hot” is at a higher level of abstraction than 26 °C, the actual temperature, even though it conveys the meaning, is a step removed from the point of observation or action, and is therefore, not fully actionable. At the higher levels of abstraction in language (room not comfortable, or I can’t stand this room), there is no possibility of understanding the reality hence no opportunity to take a clear action. Each higher level of abstraction leaves out some detail from the lower level, eg, the level “cow” leaves out details of the cow we know as Bessie, cow 2, cow 3 etc. (Figure 6). Higher levels of abstraction thus include the meanings of all levels below them, and transcend them, thereby changing the meaning and context at each level. Wealth Asset Farm asset Livestock Cow Bessie Cow we perceive Cow known to science Figure 5 – The ladder of abstraction (Hayakawa) The concept of abstraction can be applied to the problem of evaluating competencies. Competencies by definition are at a higher level of abstraction, as they integrate elements described by facts. The essence of science is systematic collection, analysis and interpretation of data. First is inductive reasoning, a process of starting with details of experience and moving to a general picture. (Shiba,1993, Figure 4). Inductive reasoning involves the observation of a particular set of instances that belong to and can be identified as part of a larger set. (Feldman,1998). Deductive reasoning is another process that begins with the general picture, and moving to a specific direction for practice and research. Deductive reasoning uses two or more related concepts, that when combined, enable suggestion of relationships between the concepts (Feldman, 1998). Inductive and deductive reasoning are basic to frameworks for research. Inductive reasoning is the pattern of “figuring out what’s there” from the details of experience. Inductive reasoning is the foundation for most qualitative inquiry and is closely associated with the kind of evaluations we arrive in competency assessment. Deductive reasoning begins with a structure, which guides one’s searching for “what’s there”. The kind of work involved in competency assessment is may be labelled as “Abstraction through Inductive Reasoning”. This methodology aptly reflects competency assessment for two reasons – one it is qualitative in nature and two it factual data that needs to be objectively evaluated or meaningful understanding of what makes mangers successful on the job. Thus the work on abstraction proposed by Piaget, Hayakawa and Shiba and the inductive reasoning process are combined here to illustrate how we can achieve a high degree of rigour and objectivity in competency assessment. Page 6 of 9 Header Space reserved for Publication ABSTRACTION THROUGH INDUCTIVE REASONING – A CASE STUDY One competency “Planning and Implementation” for a job level “X” in an organisation was chosen as a case study for establishing the proposed approach. Competency descriptor – Planning and Implementation Table 3 details out the competency definitions. This is followed the application of the abstraction method in two exercises. Table 3: Example of Competency and its Descriptors Planning and Implementation Acts in a line management capacity to translate objectives into departmental activities. Organises resources to ensure strategies are effectively implemented Negative Descriptors Positive Descriptors Is mostly managing crises Prioritises activities based on departmental needs Fails to translates requirements into actionable Makes detailed 5W, 1H plans outputs with timelines Is able to execute actions Does not prioritise activities Handles multiple projects without delays Is happy working at a superficial level Follows the plan through and ensures completion Is surprised by events Thinks through the possible issues in implementation Decides action on an ad-hoc basis Does not commit without having a full understanding of Does not follow up on plans the solution Is unable to estimate roadblocks to implementation Ensures activities are completed on time Fails to make reasonable resource estimation and Identifies resources to minimise project overruns allocation decisions Plans for quality and puts quality first, without shortcuts Gives unclear directions Finds countermeasures in time Allows target to slide when faced with resource Breaks up costs and deploys down, plans for control of constraint operational costs Escalates tasks to the next higher level Puts in place clear metrics for effective implementation of organisational goals If we observe closely there are three levels of abstraction that we encounter in competency analysis. The first level that we call the first order abstraction resides in the indicators or criteria. The second order of abstraction is the “definition” that offers a slightly broader understanding of the concept. At the top is the “competency label” itself, what we call the third level of abstraction in this case (Table 2) the label is “Planning and Implementation” All this abstraction emanates from what a person would demonstrate in a particular situation or an exercise in an assessment centre or a development centre. Assessment and Abstraction of Competency – Planning and Implementation To assess this competence, details of raw voice from the assessee are captured, actual facts as spoken or written recorded by the appraiser. The process of how the data can be systematically abstracted using the semantic conversions to reach a final competence evaluation and rating is shown in Tables 4 and 5. Table 4: Assessment of Competency – Tool 1, Assessor A Tool 1: Inbox Exercise (Written) Case study – New delivery head takes charge, deals with mailbox Statements / Actual work done by candidate (Bessie level statements) Groupings: 7 clusters. e.g. Cluster 1: Long term delivery problems (4 - lesser vans, 8 – driver overtime, 13 – high warehouse inventory, 21 - trucker union). Cluster 2 -10, 22 Priority : Self : Customer complaint leading to drop in sales in Region A Action : Ask for report on complaint with specific data on loose stitching as well as thread quality Add one van to reduce distribution overload Get warehouse management IT solution Report – 3 main points (late + incomplete delivery, quality of stitching, production improvement, implication and ramification of entry into environmentally sensitive products Analysis (by assessor) (Livestock level – Abstraction 2 levels higher) 6/7 positive descriptors exhibited (tick-marks on each in the matrix) 2 negative descriptors displayed (Assessed on Tasks – Organising, Prioritising, Problem Solving, Written Communication (coverage, structure) Observation (Recording by Assessor) (Cow level – Abstraction 1 level higher) 7 main headings covered out of a possible 12 Most items covered Priority of items are mostly correct, differing by one (High marked as medium or medium as low in 2 cases) All priority labels identified correctly (ref. recommended list) Most actions are appropriate and specific (addition of a van to reduce distribution overload) Completed almost all three tasks on time, last part of the third exercise was incomplete Report organisation – structure clear and logical, coverage complete Warehouse mgmt solution not analysed, jumped to conclusions without supporting data or analysis Evaluation (Farm Asset level – Abstraction 3 levels higher) Method : Start from the middle, move up or down Positive indicators outweigh negative indicators Final evaluation : 4.0 Page 7 of 9 Header Space reserved for Publication Modified method: Abstract using Same or similar words – eg,–senior, director – “grouped as top management”. Sales depot 1, warehouse grouped as “stock point”. Phrases with similar meanings or a class of phenomena. Example 1: Take decision on …tomorrow, complete loading schedule by the 2nd of next month – grouped as “schedules tasks on time” (to be read in the context of the case). Example 2: add one van, even out overtime schedule to allocate 30-33 hours for all 3 delivery men – abstract as “allocates resources optimally”. The above is an example of one tool in the assessment process. Another tool used to assess the same competence is a case presentation. Table 5: Assessment of Competency – Tool 2, Assessor B Tool 2: Case Analysis and Presentation (Written plus communication) Statements / Actual work done by candidate (or written data) (Bessie level statements) 6 sheets – Headings: Objectives of the case (merger), Customer bases (existing and revised), IT systems issues, Issues on premises plus alternatives together with cost, Staffing – current, proposed and issues, Savings Examples – Introduce online printing system facility, set-up portable cabin (cost XYZ), temporary housing in unoccupied retail outlet next door… Overall recommendations (added later) – addressed each group Analysis (by assessor) (Livestock level – Abstraction 2 levels higher) Structure evident in both written and oral presentation Shows limited understanding of commercial issues in analysis 4 indicators positive, 2 indicators negative (Assessed on Tasks – Structure, use of data, problem solving, coverage across areas, completion) Observation (Recording by Assessor) (Cow level – Abstraction 1 level higher) Brought out age group, geography, accounts – clarity about customers All stakeholder needs were identified clearly Charts were clear, and beautifully made, depicting detailed analysis of each dimension Extensive use of data in customer side, people numbers Most options were clear Aware of operations’ requirements with growth realities Did not come up with way forward initially, but did so, with facilitative questioning. Made the recommendations slide 4 min. Could not complete earlier due to lack of time Is not clear about employee realities Despite unviable operations, unwilling to close the branch Evaluation (Farm Asset level – Abstraction 3 levels higher) Displays a high level of Final evaluation : 3.5 Overall Integration Exercise Individual ratings as well as the comments (abstracted points on expressed behaviour) are brought to the final integration stage, with all assessors present. The final rating for this competency is to be arrived at through discussion and not merely as the mean scores across the two evaluations. The methodology for final consensus using abstraction is proposed as follows: Common items: establish agreement between people across the two exercises –eg, prioritises both issues and causes well, structures options correctly and presents them clearly. Delay on one task + extra time in presenting = Delay in arriving at conclusions. Items of disagreement on the same item: Step back to abstraction level 1 (lower than indicators, to assessor comments), and clarify evidence from both evaluations. Decide whether the behaviour is positive or negative in the balance. Abstract to the next higher level : eg, Uses data extensively towards decisions + summarises = Strong data based decision making. Does not complete on time. Final level of abstraction: Strong analysis and decision making, lacks speed in implementation CONCLUSION The application of the language processing method, using SI Hayakawa’s and Prof. Shiba’s “ladder of abstraction” was proposed in the determination of competencies. A case study depicting the application to one competency was discussed, with a final statement which is grounded in facts. While complementing the current HR approaches, this integrated approach goes beyond the typical assessment system methods to raise the abstraction level one at a time, without either over-generalisations or being stuck at low level details alone. The improved method can be applied in competency assessments of any kind – from a full fledged assessment or development centre to a competency based or behavioural event interview for potential recruits. Going forward, it is further proposed to include language processing (LP) methods as a part of the training curriculum for assessors. Such a training covering the LP method which clearly links the level of thought with the level of experience would enable them to go both up and down the ladder of abstraction easily, enabling assessors to be fully grounded in reality whilst making decisions. Another methodology that would aid the process of objective assessment of factual data would be the “grounded theory” proposed by Glaser & Strauss (1969). We shall deal with the notion of grounded theory and how it can enhance objectivity especially in a development centre situation in a more fundamental way in our future research. Page 8 of 9 Header Space reserved for Publication All the approaches mentioned in this paper – grounded theory, cognitive psychology, and ladder of abstraction can be used to train the evaluators to arrive at very objective assessments. This process of training will have three pronged benefits. First, it will vastly enhance the objectivity in HR assessments. Two, it will add to the process of fairness in selection of candidates and contribute in a big way to the notion of equal employment opportunities (EEO). Together with minimising between-appraiser variation, the abstraction led assessment approach will also lead to more objectivity in what is essentially a subjective human process, thus tilting the scales of such an evaluation far more towards science than an “art”. REFERENCES Athey, T. and Orth, M.S (1999). Emerging competency methods for the future. Human Resource Management; Vol. 38 (3), pp. 215-227. Best, J.B (1999).Cognitive Psychology (5th Ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Co. Boyatzis, R (1982). The Competent Manager. Wiley. Deshmukh, Mahesh (2005). Executive Coaching: A multi-method examination of Coaching Styles, Information Processing Modes and their Impact on Interpersonal Skills and Organizational Learning. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, IIT Bombay. Glaser, B. and Strauss, A. (1967). The Discovery of Grounded Theory, Chicago: Aldine. Green, P. C. (1999). Building Robust Competencies: Linking Human Resource Systems to Organizational Strategies. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Halle, M and Stevens, K.N. (1964): Speech Recognition: A model and program for research. In J.A. Fodor & J.J Katz (Eds.): The structure of language: Readings in the philosophy of language. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Hayakawa, S. I. (1941). Language in Thought and Action, George Allen & Unwin Ltd., London Liberman, P. (1967). Intonation, Perception and Language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Miyazaki, K. (1999). Building Technology Competencies in Japanese Firms. Research Technology Management, Vol. 42 (5), pp. 39-45. Piaget Jean. (1929).The Language and Thought of the Child. Kegan Paul. Prahalad, C.K.and Hamel, G. (1990). The core competence of the corporation. Harvard Business Review, Vol. 68, May-June, pp. 79-91. Senge, P. M. (1990): The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning organization, Doubleday/Currency, NY. Shiba, Shoji, David Walden (1993). Four Practical Revolutions in Management: Systems for Creating Unique Organisational Capability (2nd Ed.), Productivity Press, Portland OR, Center for Quality Management, Cambridge, MA. Shiba, Shoji (2005). The Five Step Discovery Process: Manual, CII, TQM Division, Gurgaon, India. Spencer, L. M & Spencer, S. M (1993). Competence at Work: Models for superior performance. New York: John-Wiley & Sons Inc. Page 9 of 9