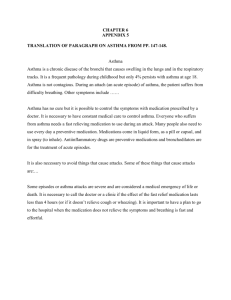

Self management protocols

advertisement