AOM 1991 - Professor Stephen J. Jaros

advertisement

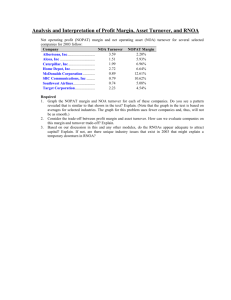

EFFECTS OF CALCULATIVE, AFFECTIVE AND MORAL COMMITMENT ON THE TURNOVER PROCESS: EVALUATION OF THREE STRUCTURAL EQUATION MODELS STEPHEN J. JAROS JOHN M. JERMIER JERRY W. KOEHLER TERRY SINCICH University of South Florida College of Business Administration Tampa, Florida 33620 (813) 974 - 4155 1 Presenter: Division: Abstract This study utilizes structural equation modeling to evaluate the impact of attitudinal commitment on employee turnover. Three different forms of attitudinal commitment (affective, continuance, and moral) were developed and were incorporated into three competing turnover models. A test of these models using data collected from a sample of employees in an aerospace firm indicated that the three forms of commitment impact on turnover indirectly through a latent "withdrawal tendencies" variable. Implications and suggestions for future research are discussed. 2 The idea that organizational commitment is in some way related to the employee turnover process has received considerable attention in recent years. Progress in documenting organizational commitment as a correlate of turnover variables is evident from meta-analyses of the research linking these concepts. Cotton and Tuttle (1986) identified organizational commitment as a highly significant (p < .0005), negative correlate of turnover based on adding Z-values in the 16 samples they reviewed. Mathieu and Zajac (1990) combined data in 26 samples and reported a mean weighted correlation corrected for attenuation between organizational commitment and turnover of -0.28. Stronger effects were reported on intention to search for job alternatives (r t = -0.60, 5 samples) and intention to leave one's job (rt = -0.46, 36 samples), variables believed to mediate the commitment-turnover relationship. Despite the abundance of research on the relationship between commitment and turnover, important problems hamper understanding of the causal processes involved. Fist, considerable disagreement about the concept of organizational commitment remains. Confusion persists about whether commitment is an attitudinal or a behavioral phenomenon (cf. Mowday, Porter & Steers, 1982; Mottaz, 1989; Randall, Fedor & Longnecker, 1990). Among attitudinal theorists, a consensus is emerging that commitment is multi-dimensional, but existing research does not completely define the components of commitment nor establish their antecedents and consequences (Meyer & Allen, 1984; McGee & Ford, 1987; Penley & Gould, 1988; Meyer et al., 1989; Randall et al., 1990; Allen & Meyer, 1990). 3 Second, analysis of the commitment-turnover relationship has not benefitted from the evaluation of alternative causal models or advances in structural equation modeling that reduce the effects of measurement errors. Usually, a single model has been specified based on extensions of Porter and Steers' (1973) framework or modifications of Mobley's (1977) framework. Without tests of competing models, especially models with latent variables, it is difficult to know how much confidence can be placed in regression-based statistical linkages between commitment and turnover. Third, measurement of commitment and turnover constructs has generated controversy. Meyer and Allen (1984), Reichers (1985) and others have argued that the most widely used measures of organizational commitment confound different types of commitment and overlap with withdrawal constructs. Mobley et al. (1979) raised several issues that recast turnover from an easily measured, "objective" criterion to one requiring greater attention and (perhaps) experimentation. The purpose of this study is to expand understanding of the commitment-turnover relationship through field res1xrch. The study's contribution rests on how successfully we address the three problems outlined above. First, we identified three distinct forms of organizational commitment: continuance, affective, and moral. Second, we specified three causal models (all with latent variables to reduce measurement error biasing) to estimate the impacts of the forms of commitment on the turnover process. Third, we proposed 4 solutions for the problems associated with existing measures of organizational commitment, and for those associated with the measurement of turnover in causal models. THEORETICAL AND METHODOLOGICAL ISSUES IN COMMITMENT-TURNOVER RESEARCH Concepts of Organizational Commitment Becker's (1960) Side-Bet Theory of Commitment has been highly influential in shaping research in this area (e.g., Ritzer & Trice, 1969; Sheldon, 1971; Hrebiniak & Alutto, 1972; Aranya & Jacobson, 1975; Stevens, Beyer & Trice, 1978; Farrell & Rusbelt, 1981; Meyer & Allen, 1984; Mottaz, 1989). This work developed the idea that as an employee makes certain investments or "side-bets" in an organization (e.g., tenure toward pensions, work friendships, organization-specific skills, political deals, job efforts), these "sunk costs" diminish the attractiveness of external employment commitment as a alternatives. psychological state Thus, in we which define the continuance employee feels compelled to commit to the organization because the monetary, social, psychological and other costs associated with leaving are binding. Two counterpoints to Becker's (1960) view of commitment have been developed. The most widely discussed form of psychological attachment to an employing organization is affective commitment. The roots of this view lie in the work of Kanter (1968) who defined commitment as "the willingness of social actors to give energy and loyalty to the organization" (p. 499), and as "the attachment of an individual's fund of affectivity to the group" (p. 507). In a similar vein, Lee (1971), Buchanan (1974a, 1974b) and Porter, Steers, Mowday and Boulian 5 (1974) directed attention to a sense of belonging and the experience of loyalty. simply Unlike continuance commitment where the attachment may reflect a cold calculation of costs and benefits, affective commitment refers to the possibility of the formation of an emotional bond. The other counterpoint to Becker's (1960) view of commitment, moral commitment, is based on internalization of norms and identification with organizational authority (Etzioni, 1975, pp. 10-11). The theme of incorporation of an organization's goals and values into one's identity has been central to organizational commitment research, but most researchers developing this theme have not linked their work to a concept of moral commitment (e.g., Brown, 1969; Hall, Schneider & Nygren, 1970; Buchanan, 1974a, 1974b; Porter et al., 1974; Steers, 1977; Morris & Sherman, 1981; Angle & Perry, 1983; Bateman & Strasser, 1984). Usually, in fact, studies of organizational commitment as identification are construed as work on affective or attitudinal commitment (see Mowday et al., 1982; Reichers, 1985; Mathieu & Zajac, 1990). In more recent work, attempts have been made to emphasize moral commitment and clarify its meaning. Ferris and Aranya (1983) reconceptualized the Porter et al. (1974) approach in terms of moral involvement. Penley and Gould (1988), Allen and Meyer (1990), and Randall et al. (1990) differentiated moral commitment from other forms and empirically examined it. Based on this, we define moral commitment as the degree to which an individual is psychologically attached to an employing organization through internalization of its goals, values and 6 missions. This form of commitment differs from affective commitment because it reflects a higher sense of duty, obligation or "calling" to work in the organization, but not necessarily emotional attachment. It differs from continuance commitment because it does not necessarily fluctuate with personal calculations of inducements or "sunk costs". Models of the Commitment-Turnover Relationship Porter et al. (1974) theorized that individuals highly committed to an organization would stay with it to assist in the realization of its goals. While this study hypothesized a direct linkage between commitment and turnover, Porter and Steers (1973) previously argued for the possibility that the turnover decision is the culmination of a psychological withdrawal process characterized by a sequence of intervening variables that mediate the commitment-turnover relationship. Similarly, Mobley (1977) presented a ten-stage withdrawal process model linking job satisfaction and turnover. refined: After testing, the model was trimmed and (1) Job Satisfaction (2) Thinking of Quitting (3) Search Intentions (4) Intent Hollingsworth, 1978). to Leave (5) Turnover (Mobley, Horner & While Mobley and his colleagues focussed on job satisfaction as the precursor to the withdrawal process, other researchers have found that attitudinal commitment plays a key role in the turnover process (e.g., Porter, Crampton & Smith, 1976; Koch & Steers, 1978; Michaels & Spector, 1982; Mowday, Koberg & McArthur, 1984; Williams & Hazer, 1986; Farkas & Tetrick, 1989). 7 However, no prior studies were uncovered that assessed the impacts of continuance, affective and moral commitment on the turnover process. Three structural equation models were specified to estimate the unique effects of all three forms of commitment (See Figure 1). Model M1: Traditional Theory. This is a modification of the Mobley et al. (1978) turnover model. Affective, continuance and moral commitment replace job satisfaction as the direct precursors of the withdrawal process. Another change is that the commitment constructs are specified as latent variables and estimated with confirmatory factor analysis. A third change involves the use of a "days stayed" variable instead of a dichotomous turnover variable. This shifts the meaning of turnover slightly, but conforms with statistical assumptions that should be met in structural equation modeling and has other advantages to be discussed. It is hypothesized that each type of commitment directly affects thinking of quitting, which leads to intent to leave the present employer, which affects the number of days stayed with the firm. In this model, commitment affects turnover indirectly (Figure 1). Model M2: Constrained Latent Correlation. This model represents the withdrawal variables as indicators of an unmeasured latent factor-withdrawal tendency. It replaces the sequential stages of withdrawal with a more cyclical and interactive view of the ways employees consider leaving the firm. This model more closely resembles cognitive psychologists' descriptions of human mental processes that emphasize vague, general orientations and lack of distinction-making in everyday life (e.g., Feldman, 1981; Langer & Piper, 1987). 8 Thus, it specifies that a change in one's level of commitment will impact the formation of an overall tendency to withdraw from or stay with the organization. The withdrawal tendency underpins more specific withdrawal concepts which derive their interrelationships from this source. Contrary to traditional theory, turnover is unrelated to the three measured withdrawal variables. Instead, it depends most directly on the unmeasured withdrawal tendency variable (Figure 1). Model M3: Saturated Latent Correlation. This model is identical to M2 except that it includes direct paths between each type of commitment and days stayed (Figure 1). It is based on research findings suggesting that attitudinal variables contribute significantly to the prediction of turnover beyond that attributable to behavioral intentions (Arnold & Feldman, 1982; Steel & Ovalle, 1984; Miller, Powell & Seltzer, 1990). It allows for the possibility that the forms of commitment impact the turnover decision both directly and indirectly. Measurement Issues Disagreement over the nature of organizational commitment has resulted in the development of measuring instruments that may not be valid. For example, Reichers (1985) pointed out that the scale used most frequently to Commitment measure attitudinal Questionnaire--OCQ" commitment, (Porter extensively with intent to quit items. et the al., "Organizational 1974), Tetrick and overlaps Farkas (1988) discovered that the negatively worded items of the OCQ lacked stability. And, since the Porter et al. (1974) concept of commitment is focused on intent to quit, willingness to exert 9 effort, and moral beliefs and cognitions, there are reasons to doubt the wisdom of exclusive reliance on the OCQ to measure attitudinal commitment. In research where the objective is to assess the impact of specific forms of commitment on the turnover process, the OCQ has limited value. Thus, we built on work by Meyer and Allen (1984), Allen and Meyer (1990), Randall et al. (1990) and others in estimating the effects of more specific measures of the forms of commitment. Dichotomous measurement problems in causal modeling. of the turnover variable presents According to Bollen (1989), conducting LISREL analyses with one or more categorical endogenous variables can lead to biased parameter estimates and invalid statistical tests. To avoid this, we measured turnover using a ratio variable that was scaled as the number of days the employee remained with the organization after the questionnaire was administered. In addition to conforming with statistical assumptions underlying maximum likelihood estimation in LISREL, the days stayed variable allows a more precise estimate of the impacts of commitment and withdrawal variables. It allows prediction of how long employees stayed before leaving, if they did leave. METHOD Sample, Context and Procedures The study is based on data obtained from a sample of personnel employed by an aerospace firm located in a major metropolitan area in the southeastern U.S. The firm was a wholly owned American subsidiary of a multinational corporation (revenues = $700 million per year; 20,000 employees) headquartered in London, England. 10 Approximately four weeks prior to collection of questionnaire data, intensive, semi-structured interviews were conducted with 62 employees (about 21 percent of the organization's members). Interviews were conducted at the workplace during normal working hours and required from 30 minutes to three hours to complete. Prior to the interviews, a letter from the firm's general manager was distributed to all employees. It guaranteed them total confidentiality and encouraged them to be candid and sincere in their responses. Interviews were supplemented by several partial days of on-site observation to develop an understanding of the firm's products, physical layout, task interdependencies, etc., and to built rapport with employees. After completing these activities, a questionnaire was designed and administered to 92 percent of the organization's employees (270 of 293) during normal working hours. Completion time was between 75 and 100 minutes, including time taken to explain the study and the survey. Respondents were assured of total confidentiality. Five respondents missed questionnaire items and were deleted from the multivariate analyses. Sixty-eight percent of the sample were male. The average age of respondents was about 35 years (one-third were 30 years old or younger, one-fourth were older than 45 years). Eighty-one percent completed schooling beyond high school, 26 percent held college diplomas, and an additional 15 percent had begun graduate study or earned a graduate degree. Forty-two percent had been with the firm two years or less, another 44 percent between 2 years and 10, and 14 percent had more 11 than 10 years tenure. percent had served in the military. Approximately 22 percent of the sample were engineers, 22 percent were technicians, 17 percent were hourly workers (mostly assigned to manufacturing), 23 percent were clerical and support staff, and 16 percent were administrative, managerial or supervisory. Measures The continuance form of organizational commitment was measured with three items developed by Meyer and Allen (1984). The items were chosen to capture the idea of sunk costs and investments while not confounding the concept with options and alternatives available. Responses were made on seven-point scales ("strongly disagree-strongly agree"). One of the items was reflected. In previous research (Meyer & Allen, 1984; Allen & Meyer, 1990), the continuance commitment scale was unrelated to affective and moral commitment measures. Becker's (1960) notion of side-bets can be assessed more appropriately with this measure. The affective form of organizational commitment was measured with 14 bipolar adjective items written for this study. scale, respondents were asked to report the Using a feelings seven-point they usually experience when thinking of their employing organization. Sample items include: sadness-happiness; pleasure-pain; anger-peace; and loyalty- disloyalty. Five of the items were reflected. The moral form of organizational commitment was measured with 4 items developed by Gould and Penley (1982) and Werbel and Gould (1984). The items reflect a sense of duty and dedication to the 12 organization and its mission. Responses were made on seven-point scales ("strongly disagree-strongly agree"). Allen and Meyer's (1990) normative commitment scale was not available when the study was conducted, but the items appear to overlap considerably with concepts of staying and leaving. In testing commitment-withdrawal models, it was preferable to avoid this degree of overlap. Thinking of quitting the organization and intention to search for a new job, two aspects of the tendency to leave concept, were measured with single items written by Mobley et al. (1978). made on five-point scales (never-constantly; Responses to both were very unlikely-certain). Bluedorn's (1982) two items were used to measure intent to leave the organization. The simplicity and straight-forward character of withdrawal tendency variables has led researchers to rely on one and two item measures. Contrary to popular belief, this does not produce inherently unreliable and invalid estimates. Ordinarily, measurement of turnover is uncomplicated: employees sign questionnaires and personnel records are checked months or years later to determine employment status. If the employee left, the turnover criterion is coded 1; if the employee did not leave, the turnover criterion is coded 0. Due to the prevailing climate in the organization at the time of the study, it was decided that the questionnaire data would be more useful if no names were requested. Instead, respondents were asked to put a code on the front page of their survey that would be memorable to them without revealing their identity (e.g., mother's maiden name). When an employee left the firm, the Employee Relations Director asked for the 13 survey code during the exit interview. employee could not In the few cases where the remember the code, it was possible to match demographic data from the survey with personnel records to identify the respondent. Turnover data were collected 99 weeks after collection of the survey data. firm. Forty-eight of the original 270 respondents had left the Since the exact date of separation was known, a "days stayed" variable was coded. Hypothetically, this could range from one (representing a respondent who separated the day after the survey was administered) to 688 (representing a respondent who did not separate). Analyses Means, standard deviations, bivariate correlations, and internal consistency estimates were calculated. Principal axes factor analysis with both orthogonal and oblique rotation was then used to determine the dimensionality of the organizational commitment construct. Identification of Models. Before attempting to estimate the models, it must be determined if unique values exist for the unknown model parameters. This is commonly known as the "identification" step in structural equation modeling. A model is identified if all unknown model parameters are identified, i.e., if all parameters can be written as algebraic functions of the elements of the sample covariance matrix of observed variables. Identified (or overidentified) models have sufficient information available in the sample estimate the model parameters. covariance matrix to uniquely An underidentified model has at least one parameter which is not identified; 14 there is insufficient information available in the sample covariance matrix to estimate the parameters of this type of model. Upon scaling the latent commitment variables (this amounts to constraining the path coefficient for one of the observed x's to 1 for each latent variable), we can apply the recursive rule (see Bollen, 1989) to establish that Models M1, M2, and M3 are identified. Evaluation of Models. The three identified structural models were fit and analyzed using the LISREL 7 software package (Joreskog & Sorbom, 1988). The sample covariance matrix, based on complete data (n=265 cases) for the 25 observed variables (21 commitment variables and 4 turnover variables), was used as input to LISREL in order to obtain maximum likelihood estimates of the path coefficients. Measures of Overall Model Fit. Table 2 lists several overall fit measures for the models. Four goodness of fit measures are provided automatically by LISREL: (1) the chi-square statistic; (2) the root mean square residual (RMSR); (3) the goodness-of-fit index (GFI); and, (4) the adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI). Each of these statistics measures how well the reproduced covariance matrix, based on the specified constraints, estimates the observed (sample) covariance matrix. Several other goodness-of-fit indices designed to allow a comparison of fit of two nested models were also calculated (Table 2): (5) Bentler and Bonett's (1980) normed-fit index (NFI), which measures the improvement in fit for the model in question relative to some baseline, or more restrictive, model; (6) the parsimonious normed-fit index (PNFI), suggested by James et al. (1982), which adjusts the NFI for 15 degrees of freedom; (7) the parsimonious goodness-of-fit index (PGFI), proposed by Mulaik et al. (1989), which adjusts the GFI for degrees of freedom; and, (8) the relative normed-fit index (RNFI), an index designed to assess the relative fit of the structural relationships among the latent variables proposed by the model, independent of the measurement portion of the model (Hertzog, 1990; Mulaik et al., 1989; and Lerner et al., 1988). RESULTS Factor Analysis The results of an SPSSx principal axes factor analysis of the 21 measures of commitment are summarized in Table 1. The SPSS x program extracted three factors, which account for 56% of the total variance present in the 21 measures. The factor loadings for both an orthogonal (VARIMAX) and oblique (OBLIMIN) rotation of the three factors are shown in Table 1. Focusing only on factor loadings that exceed .4 in absolute value, a clear pattern emerges: commitment one factor is a linear combination of the 14 affective variables (X4 - X17), while the remaining two factors represent continuance commitment (X1 - X3) and moral commitment (X18 X21), respectively. This "clean" structure identified in the factor analysis provides strong statistical support for the notion of continuance, affective, and moral commitment as latent variables in the structural equation models proposed in this study. LISREL results. The chi-square tests in Table 2 reveal that all models must be rejected (p < .001) as the "perfect" fit according to the chi-square test. However, the three models provide, at a minimum, an adequate fit to the 16 data based on the other goodness-of-fit measures listed in Table 2. First, consider the Traditional Theory Model, M1, shown in the first row of Table 2. The fit statistics point towards a reasonable fit to the data: GFI, AGFI, NFI0, and PNFI0 all exceed .8 (with NFI0 approximately equal to .9); PGFI is approximately .7; and both NFIb and PNFIb are near .6. The two models which propose a single latent withdrawal variable as the underlying cause of THINKQ (Y1), SEARCH (Y2), and INTLV (Y3), are M2 and M3. These two models are nested (i.e., the free parameters of M2 are a subset of the free parameters of M3). Consequently, we can compare them inferentially using a likelihood ratio (chi-square) test. The null hypothesis takes the form Ho: γ4 = γ5 = γ6 = 0 Note that the parameters specified in Ho are the path coefficients for the three additional paths hypothesized by M3. The test statistic is X2 = (X2)2 (X2)3 = 4, with df = df2 - df3 = 3. For this small value of X2, there is insufficient evidence to reject Ho (p > .10); hence, the three additional paths proposed by M3 do not improve the fit of the structural model. In the interest of parsimony, M2 is deemed superior to M3. How does M2 compare to the traditional model, M1? For each of the fit indices reported in Table 2, the index for M 2 always exceeds those for M1. The differences range from small (NFI0 values of .932, and .898 for M2, and M1, respectively), to moderate (PNFIb values of .712, and .586), to large (RNFI values of .997, and .602). It is important to note that the largest differences occur with RNFI. This implies that the goodness-of-fit attained by M1 is somewhat inflated 17 due to the large number of parameters estimated in the measurement portion of the model. When the fit index is calculated independent of the measurement portion of the model, M2 is clearly the superior of the two models. Detailed Analysis of Model M2 Although we must reject the hypothesis that Model M 2 is the "perfect" fit (X2 significant at p < .001), the goodness-of-fit measures in Table 2 suggest strongly that M2 fits the data adequately, i.e., adequately reproduces the observed covariance matrix. In addition, an examination of the parameter estimates and normalized residuals indicated that the model was not misspecified. The overall coefficient of determination for the measurement portion of the models reported at the bottom of Table 3, is .990. This high overall R2 summarizes the joint effect of the latent variables on the observed variables and indicates that the observed X's are excellent indicators of the latent commitment variables. The R 2 values for the structural equations relating the latent variables C 1-C3 to W, and W to y4, are .663 and .078, respectively. Thus, the three latent commitment variables account for over 66% of the variance in the tendency for a worker to withdraw from the organization, while the latent withdrawal tendency variable accounts for about 8% of the variance in days stayed. The overall R2 for the structural portion of the model, which measures the joint effect of the latent variables Ci and W on days stayed is approximately 66%. The overall fit measures, normalized residuals, individual parameter estimates and corresponding t statistics, and overall coefficients of 18 determination all support Model M2 as a reasonable representation of the causal structure underlying the withdrawal tendencies of workers. Based on the asymptotic standard errors (shown in Table 4), approximate 95% confidence intervals for the effects of the latent variables on days stayed were computed. These intervals, given in the last column of Table 4, are interpreted as follows: C1: A 1-point increase on the latent continuance commitment scale leads indirectly to an increase in the length of stay with the organization between 7.18 and 23.12 days; C2: A 1-point increase on the latent affective commitment scale leads indirectly to an increase in length of stay between 11.52 and 37.67 days; C3: A 1-point increase on the latent moral commitment scale leads indirectly to a change in length of stay ranging from -5.47 to 10.98 days; W: A 1-point increase on the latent withdrawal tendency scale leads directly to a decrease in the length of stay between 34.02 and 90.99 days. Notice that the 95% confidence interval for C 3 includes 0, implying that the indirect effect of moral commitment on DAYS is nonsignificant. This result was expected since γ3, the path coefficient relating C3 to W, is not significantly different from 0. Thus, while the effects of continuance and affective commitment on "days stayed" are statistically indistinguishable from each other, both have a greater impact than moral commitment. DISCUSSION The purpose of this study was to expand understanding of the commitment-turnover relationship by clarifying the dimensionality of the 19 commitment construct, evaluating alternative causal models, and addressing problems associated with the measurement of commitment and turnover variables. Each of these areas will be discussed in turn. First, the conceptualize commitment: results and of the measure study three indicate distinct that forms we of are able to organizational affective, moral, and continuance commitment. This provides further support for the idea that attitudinal commitment is multi-dimensional in nature. In addition, it supports the contention (Allen & Meyer, 1990; Randall et al., 1990) that affective and moral commitment are indeed distinct and separate concepts. Thus, further research could focus on testing for the separate impact of each form of commitment on other potential correlates, such as job performance, absenteeism, and job satisfaction. Second, the use of causal models enabled us to compare two alternative theories: Mobley et al.'s (1978) model; and latent variable models based on findings from cognitive psychology. Although the Mobley et al. model provided an adequate fit to the data and was otherwise found to be useful, the clear superiority of the latent withdrawal tendencies model is noteworthy. It suggests that researchers working in this area can benefit from studying findings in the field of cognitive psychology. These results show that individuals' typically exhibit vague, general orientations and tendencies toward a particular behavior (such as turnover) - as opposed to the distinct, sequential withdrawal process proposed by Mobley, et al. (cf. Feldman, 1981; Langer & Piper, 1987). 20 Third, the use of alternative measures of commitment and withdrawal process variables that do not confound the different types of commitment or overlap each other resulted in simple structure estimates of commitment constructs and more realistic estimates of the effects of commitment on the turnover process. In addition, the use of a "days stayed" variable, rather than a simple dichotomous turnover variable, permitted the actual prediction of an employee's tenure with the organization based on his or her level of commitment. Finally, we must note two important limitations of this study. First since researchers have questioned the usefulness of intervening withdrawal variables proposed by Mobley et al., such as thinking of quitting (Bluedorn, 1982) and search intentions (Price & Mueller, 1981), causal models using structural equation methods could be used to compare models that trim these stages from the withdrawal process. In fact, we did test a total of nine competing models, including ones that trim Thinking of Quitting, Intent to Leave, and Search Intention. The results indicated that all three of these intervening variables were valuable trimming them did not improve the usefulness of the Mobley, et al. model. However, because of space constraints, we were unable to fully report the results of these additional tests. Second, our data shows that 48 out of 275 sampled employees (18%) had left the firm after 99 weeks - a rate of turnover lower than that typically experienced in many industries, particularly service industries. This generalizability of our findings. 21 could somewhat limit the Conclusion In summary, this study makes important contributions to the study of the commitment-turnover relationship. The ability to measure three separate forms of commitment highlights the need for future research that would further refine the concept of organizational commitment. Also, because our findings show that the types of commitment differed in their relative impact on the turnover decision suggests that future research could explore the reasons behind these differences. The identification of the latent Withdrawal Tendencies variable within the commitment-turnover process indicates that future research should focus on the usefulness of latent variables, comparing these to more precise, sequentially ordered cognitive constructs. Finally, it seems clear that commitment-turnover research should utilize causal modeling techniques, such as LISREL, which provide more sophisticated measures of overall model fit, and permit the comparison of competing turnover models. Each of these suggestions would further our understanding of the relationship between organizational commitment and employee turnover. 22 REFERENCES Allen, N. & Meyer, J. 1990. The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance, and normative commitment. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63: 1 - 18. Becker, H. 1960. Notes on the concept of commitment. American Journal of Sociology, 66: 32 - 40. Buchanan, B. 1974a. Building organizational commitment: The socialization of managers in work organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 19: 533 - 546. Farkas, A. & Tetrick, L. 1989. A three - wave longitudinal analysis of the causal ordering decisions. Journal of of satisfaction and commitment on turnover Applied Psychology, 74: 855 - 868. Feldman, J. 1981. Beyond attribution theory: Cognitive processes in performance appraisal. Journal of Applied Psychology, 66: 127 - 148. Mathieu, J. & Zajac, D. 1990. A review and meta - analysis of the antecedents, correlates, and consequences of organizational commitment. Psychological Bulletin, 108: 171 - 194. Mobley, W. 1977. Intermediate linkages in the relationship between job satisfaction and employee turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 62: 237 - 240. Mobley, W., Horner, S. & Hollingsworth, A. 1978. An evaluation of the precursors of hospital employee Psychology, 63: 408 - 414. 23 turnover. Journal of Applied Mottaz, C. 1989. An analysis of the relationship between attitudinal commitment and behavioral commitment. Sociological Quarterly, 30: 143 - 158. Porter, L., Steers, R., Mowday, R. & Boulian, P. 1974. Organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover technicians. Journal of Applied Psychology, among psychiatric 59: 603 - 609. Reichers, A. 1985. A review and re - conceptualization of organizational commitment. Academy of Management Review, 10: 465 - 476. 24 TABLE 2 Lisrel Results Model Description df X2 RMSR GFI AGFI PGFI NFI0 PNFI0 NFIb PNFIb RNFI M1 Traditional 270 680 6.0 .841 .809 .699 .898 .808 .606 .586 .602 M2 Constr. L.V. 269 542 4.2 .862 .833 .713 .932 .836 .738 .712 .997 M3 Full L.V. .863 .832 .706 .932 Null 266 538 300 4272 11.1 279 1311 11.1 889 .791 .754 11.1 3.0 .198 .131 .674 .620 .183 .000 .579 .672 .846 .000 .779 .408 .826 .740 .000 .705 M base .000 Mcfa M null Baseline No LV Cor. 276 .403 Note: All chi-square tests significant at p < .001. TABLE 3 Analysis of Path Coefficients of Model M2 Causal Relation Parameter ML Estimate Standard Error t-value C1 ---> W γ1 -.242 .032 -7.657 C2 ---> W γ2 -.393 .054 -7.351 .663 C3 ---> W γ3 -.044 .065 -.675 W ---> y4 β1 -62.506 14.243 -4.388 .078 Notes: c = constrained constant Overall R2 for measurement portion of model = .990 Overall R2 for structural portion of model = .663 R2 TABLE 4 Effects of Latent Variables on DAYS (y4): Model M2 Latent Variable Total Effects Estimate Standard Error Approx. 95% CI Continuance Commitment (C1) γ1β1 20 15.155 3.985 (7.18, 23.12) Affective Commitment (C2) Moral Commitment Withdrawal Tendency (C3) (W) 24.595 γ2β1 γ3β1 β1 2.754 -62.506 21 6.536 4.111 14.243 (11.52, 37.67) (-5.47, 10.98) (-90.99, -34.02)