The Romanisation of Celtic Gaul

advertisement

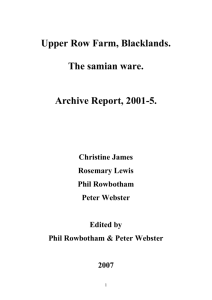

NSW Premier’s Westfield’s History Scholarship 2009 STUDY TOUR REPORT THE ROMANISATION OF CELTIC GAUL NAME: Mr Ronald Griffith POSITION: Teacher WORKPLACE: James Fallon High School WORKPLACE ADDRESS: Fallon Street, Albury North 2640 NSW AIMS OF THE STUDY TOUR 1. To investigate the definition of ‘romanisation’ 1.1 Introduction One aim of my study tour of France was to investigate the concept of ‘romanisation’ within a small canvas, namely, ‘Roman Gaul’. ‘Romanisation’ has now become anhistorically loaded term. It was first hinted at by the German scholar Theodor Mommsen (1886) and subsequently coined by the British historian F. Haverfield (1912). Their concept of culture-contact with gradual change brought largely about by assimilation replaced a more simplistic view that the Romans conquered, occupied and finally departed; in short, oblivious to cultural interaction.1 ‘Romanisation’ became ‘the dominant paradigm’ for most of the 20th century.2 It originated in an era ironically called ‘imperialism’, during which colonial governments including France, Germany and England were justifying their Asian and African conquests in terms of cultural, religious, scientific and moral superiority. Mommsen and Haverfield argued that the Roman Empire rightly imposed their cultural superiority upon ‘barbarians’.3 It was imposed from above; it was largely one-sided; and it had a valid “civilising” mission. To these cultural historians, ‘romanisation’ laid the foundations of Western civilisation.4 “ ‘Romanisation’ might be compared to ‘westernisation’ or ‘modernisation’, as concepts denoting a progressive movement through which communities and individuals advanced towards a higher level of civilisation or development, by shedding the least desirable features of ‘traditional’ society.”5 Recent scholarship recognises that ‘romanisation’ and another anthropologically-based term, ‘acculturation’ (imitation of a superior culture) are loaded words or umbrella terms that have oversimplified and may even conceal the reasons for change. Some scholars even ‘detest’ the word calling it ‘ugly and vulgar’.6 According to Professor Greg Woolf (2003) the best definition we can use is that ‘romanisation’ is “a series of cultural changes that created an imperial civilisation” with provincial contrasts, yet, fitting into a discernible pattern.7 Most scholars agree that new ways are needed to assess the impact of Rome on its many provinces. Woolf (2003) prefers to think in terms of the expansion of Roman society driven by two ubiquitous phenomena: cultural and consumer revolutions. A. Gardner, “Fluid Frontiers: Cultural Interaction on the Edge of Empire”, Stanford Journal of Archaeology, vol. 5, 2007, p.45 2 Ibid. p.45 3 Haverfield (1912) wrote, “But the Roman Empire was the civilised world; the safety of Rome was the safety of all civilisation. Outside roared the wild chaos of barbarism.” Taken from G.Woolf’s, Becoming Roman-the Origins of Provincial Civilization in Gaul, (Cambridge, 2003), p. 4. 4 G. Woolf, Ibid., p.4 5 G. Woolf, “Beyond Romans and natives”, World Archaeology, Vol. 28(3) 1995, p.339. 6 S.E. Alcock, “Vulgar Romanization and the Dominance of Elites”, in S. Keay and N. Terrenato eds., Italy and the West- Comparative Issues in Romanization, (Oxford, 2001), p.227 7 G. Woolf (2003), op. cit. p.7. 1 1.2 The ‘cultural revolution’ Firstly, a ‘cultural revolution’ engulfed the empire.8 It was modelled on a similar phenomenon in Rome that ‘set the pattern’ for new tastes9. Roman elite society especially during the Augustan principate saw ‘frenetic cultural activity’ 10 in education of the arts like poetry and rhetoric, the construction of monumental architecture such as impressive fora and theatres and, of course, the pursuit of otium or leisure activities such as bathhouses and amphitheatres. An inherent Roman patrician more or value in the ‘cultural revolution’ was humanitas. Woolf (2003) defines humanitas as a combination of ‘noble conduct’ (benevolence when appropriate, discipline when needed and doing one's duty to the State when required) and ‘culture’ (education and lifestyle).11 Although initially this cultural expansion was forced brutally on most Roman provinces including Gaul, it was the new ‘allied’ Gallic elite who emerged from the rubble created by the Gallic Wars and to whom most credit should be given in creating a new ‘Gallo-Roman’ society. Like many other wise elites throughout the ‘new age’ empire, the Gauls enthusiastically embraced the ‘cultural revolution’ with its central notion of humanitas. As Susan E. Alcock (2001) states: “It would be impossible to deny that local elites- their activities, their prioritieswere the imperial fulcrum, the point around which so much else of the dance of empire revolved”.12 1.3 The ‘consumer revolution’ A second phenomenon that swept over the empire from the late 1st century BC was a ‘consumer revolution’. An economic boom especially in the ‘formative years’13 of the Julio-Claudian principates (last quarter of the 1st century BC to the first half of the 1st century AD) was characterised by an amazing growth in the variety and quantity of consumer goods and services throughout the empire. Judging from the archaeological records as witnessed in French museums and archaeological park sites, all levels of society profited from pax Romana or Roman peace. Therefore, my aim was to test this new definition of ‘Romanisation’; a process of selective adoption and adaption of Roman culture by the new elite of Gauls. In particular, the Aedui tribe from Burgundy would be assessed. The Aeduan elite enthusiastically changed or ‘syncretised’ Celtic society by creating a mixture of old (Celtic) and new (Roman) cultures into a new ‘Gallo-Roman’ culture. This process, although slow in terms of a person’s lifetime, proceeded in the context of a ‘consumer revolution’ and ‘cultural revolution’ throughout the Mediterranean world. The origin of these two economic and social phenomena was in the late Roman Republican era (1st century BC) and greatly accelerated in the Augustan/Julio-Claudian principates. G. Woolf, “The Roman Cultural Revolution in Gaul” in S. Keay and N. Terrenato eds., op cit, p.175 Ibid. p.176 10 Ibid. p.174 11 G. Woolf (2003), op. cit., pp55-56 12 S.E. Alcock, op cit., p.229. 13 G. Woolf (2003), op. cit., pp.193-194. 8 9 2. To learn about the Celts of Gaul Before one can appreciate cultural change in Gaul, it is important to appreciate what society was like in Gaul before the Roman conquest.14 The premise of ‘romanisation’ that the Celts of Gaul were ‘barbarians’, who were civilised by the Romans, seems an important one to research. Therefore, it soon became obvious to me that another aim of my study tour was to visit sites and museums in France that specialised in Celtic and Gallic research and archaeology. There was to be no better place to begin my research of Celtic society in Gaul than at the European Archaeological Research Centre at Bibracte, Burgundy. FINDINGS 1. The Celts of Gaul 1.1 The European Archaeological Research Centre at Bibracte, Burgundy In the past Bibracte was the capital of the Gaulish tribe, the Aedui; today, it is an archaeological site, museum and research centre. In fact, Bibracte is the European Archaeological Research Centre. Bibracte oppidum or hillfort is situated on the top of Mont Beuvray, part of the Morvan Mountains in today’s Saone-et-Loire and Nièvre Departments, Burgundy. The plateau on top consists of three hills and the site was fortified with a wall that extended over seven kilometres using a construction method called murus gallicus timber beams fixed together with long iron nails then faced with stone blocks. A recently discovered second fortification wall of 5.2 kilometres has revealed an enclosure of nearly 135 hectares enlarging the oppidum to 335 hectares. This equates to the size of Paris under Charles V’s reign in the late 14th century AD. It is estimated that a population of 5,000 to 10,000 people lived in the oppidum. Evidence of town planning before the Roman conquest, a monumental water source with possible equinox positioning, terracotta tiles, a wide causeway with workshops either side, mining activity and an early forum structure all point to a sophisticated Celtic culture not ‘barbarians’. Today this monumental Celtic/Gallo-Roman site attracts archaeologists and universities for both teaching and research purposes. During my stay I was taken on a detailed tour by Pascal Paris, Bibracte’s resident archaeologist. This tour included: Bibracte’s recent burial discoveries by Vienna University outside the main gateway called ‘Porte du Rebout’ An explanation of the use of geophysical and aerial techniques to discover new possibilities for excavation - Pascal is hopeful that they have recently found another gateway to the oppidum 14 The Roman conquest in southern Gaul (124 BC) occurred much earlier than other areas of Gaul that were conquered during Caesar’s Gallic Wars (58-52 BC). This is an important distinction in terms of the minimal Celtic identity found in southern France today. Past excavations and mistakes by Bibracte’s two main 19th century archaeologists, Jacques-Gabriel Buillot and Joseph Déchelette A visit to Toulouse University’s excavation site and an interview with Professor Cauuet about her exciting new discovery at Bibracte-gold! An inspection of a wealthy Gallo-Roman villa complex including the recent discovery of a forum that, surprisingly, dates to before Caesar’s conquest of Gaul. The creative cover for the site, designed by the architect of Charles De Gaulle Airport in Paris, reveals a serious conservation effort to protect archaeological remains. Apart from the archaeological role at Bibracte’s Mont Beuvray oppidum, the European Research Centre also has a modern, world-class facility in the nearby small village of Glux-en-Glenne. The Research Centre’s facilities are ‘fantastique’. They include separate workshops for metal and ceramic work, a graphic design department, a 24/7 library research facility with special archaeological collections, a conference hall and classrooms for visiting school children including primary students. School children are invited to spend up to one week free of charge at Bibracte where they gain an appreciation of archaeology and their European/national heritage. The research centre also has delegated workrooms for visiting research teams from all over Europe, a large administrative area and an enormous underground archive ‘depot’ where the temperature is kept at the optimum conservation level. An extension to this storage area is currently under way. In another building complex in the village of Glux-en-Glenne there is located accommodation for visiting researchers and students. In the large cafeteria archaeologists dine alongside visiting primary students. French egalitarianism in practice! Bravo! The European Archaeological Research Centre’s headquarters (Glux-en-Glenne) Bibracte’s museum at the foot of the oppidum plays a key educational role. Again the museum is modern, well-lit and spacious. A multimedia approach is used to explain the important question of “Who were the Celts?” The museum’s exhibits from Bibracte and other Celtic sites in Gaul revealed a general high level of craftsmanship, artistic achievement and functionality of items in pre-conquest Gaul. This was evident from the quality of metal tools, weapons and personal items coupled with the quality of ceramics. Importantly, Bibracte’s museum dispels the myth that the Celts of Gaul were ‘barbarians’. 1.2 Other Archaeological Sites and Museums in Burgundy Bibracte’s Research Centre proved to be a convenient base in Burgundy that enabled me to visit other nearby Celtic archaeological sites: Chatillon-sur-Seine, Alesia, Dijon Museum and Chalonsur-Saône Museum. The Burgundian town of Chatillon-sur-Seine has a newly renovated museum along with the Celtic goddess Sequana’s sacred ‘La Source de la Seine’. Chatillon’s museum is famous for the grave goods of the ‘Princess of Vix’ that were found in 1953 at the foot of Mont Lassois, an early Celtic Halstatt oppidum and temple site (700-400 BC). The ‘Vix Krater’ is a masterpiece in bronze created by Greeks in southern Italy (a colony of Sparta?) and the size and quality of its decoration defy belief. Holding 1100 litres of wine, the Vix Krater stands 1.64 metres high, weighs 208 kilograms and its walls are no thicker than 1.2 mm. The body of the vase is formed by a single sheet of beaten metal. Impressive statistics! This was no palace item kept by ‘barbarians’! 1.3 Other Oppida in Gaul Apart from the oppidum at Bibracte, three other oppida I visited were Gergovie, Chateaumeillant and Argenton-sur-Creuse (Argentomagus). The archaeological record in their respective museums revealed complex Celtic societies in Gaul prior to Roman conquest. In Chateaumeillant Museum there are many wine amphorae on display that were found in excavations of the Celtic Bituriges Cubi tribe oppidum at Chateaumeillant. Roman writers inferred that the Gauls were barbaric drunks who would sell a slave for an amphora of wine.15 However, this portrayal of the Gauls was out of religious, chronological, geographical and social context. For example, it is now believed that wine was used in Celtic feasts to enhance the status of warrior nobles among their supporters as well as to satisfy ritualistic beliefs.16 Another theory suggests that creative, Celtic artisans were paid with wine. 17 Supply and demand factors may also account for Sicullus’ harsh judgement of Gauls. Judging from amphorae deposits, wine was scarce in non-Mediterranean Gaul before the late 2nd century BC and it was rare in certain areas of Gaul even during the early 1st century BC.18 15 Diodorus Siculus, Library of History, (5.26.3) See M.E. Loughton’s, “Getting Smashed: The Deposition of amphorae and the drinking of wine in Gaul during the late Iron Age”, Oxford Journal of Archaeology, vol.28 (1) 2009, p85. He warns about using this example as a “generalizing model of behaviours over several centuries and over wide areas”. Loughton (2009) suggests the possibility that Siculus’ ‘barbaric’ Gaul could be an alcoholic who is willing to give up anything in a desperate attempt to get another fix. 17 Ibid. p. 91 18 Ibid. p. 85 16 1.4Conclusions about the Celts of Gaul The Celts of Gaul have been much maligned by the Roman sources of the mid 1st century AD including Tacitus, Strabo and Pliny the Elder. The classical writers tended to glorify the Roman achievement by the Celts of Gaul being 'worthy opponents' but 'primitive barbarians'.19 The archaeological record contradicts the ancient written record because the Celts of Gaul had already developed many sophisticated features in their tribal societies such as: roads and river transport metallurgy skills a type of urban living in impressive oppida a complex trading and exchange network within Gaul and far beyond a currency system and manufacture of coinage the use of the pottery wheel in ceramics patterned woollen cloth making using threads of different colours, and an agriculture based on diversity that can withstand famine rather than the Roman mono-cropping or ‘bread basket’ approach20. Therefore, the foundation of economic prosperity was already there when Caesar’s legions entered central Gaul. The fact that Caesar made his fortune in Gaul is well recognised.21 This land is very productive! Evidence of the land’s Celtic agricultural productivity was also prevalent in the archaeological record in the Gallo-Roman sites and museums that I visited. 2. The new definition of ‘romanisation’ 2.1 Introduction ‘Romanisation’ was partly the patrician belief or mission to civilise the barbaric world. Central to this more was humanitas- noble behaviour and culture. However, Rome needed more than an arrogant attitude and its legions to integrate a vast empire. Two phenomena were largely responsible for maintaining the Augustan peace (pax Romana) especially in Roman Gaul: the ‘consumer revolution’ and the ‘cultural revolution’. 2.2 The ‘consumer revolution’ The new regime that we call Roman Gaul saw a society that increased its wealth exponentially as judged by the increase in quantity and variety of ‘consumer goods’ found in sites throughout France. Whilst the quality of consumer goods had always been evident in Celtic society, it is the wide range of goods, the many innovations in technology to produce them and the vast increase in numbers that stand out in this “new world of goods”22 , Roman Gaul. 19 B. Cuncliffe, The Ancient Celts, (Oxford, 1999), p7) See 25 year study of Burgundy, ‘The French Project’, led by Professor Carole Crumley in C.L. Crumley and W.H. Marquardt eds. Regional Dynamics: Burgundian Landscapes in Historical Perspective, (San Diego, 1987). 21 No doubt slaves added to his coffers. 22 G. Woolf, Becoming Roman- The origins of Provincial Civilization in Gaul, (Cambridge, 2003), pp.169-174 20 A huge ‘cultural gap’ emerged in the 1st century AD that separated Roman Gaul from their Celtic ancestors. Consumer items like red tile roofs instead of thatch, a plethora of bronze household items like tweezers and oil lamps, ubiquitous ceramic/bronze statues to personal deities as well a vast array of red shiny ceramics called terra sigillata provide proof of this new ‘Gallo-Roman’ culture. 23 One of the biggest surprises I experienced in France was the realisation that the Rhone River is full of consumer goods. It’s believed that there were far more artifacts in the Rhone River near the town of Arles than in its museum. In fact, it is impossible to excavate it all because of the cost and storage issues. A life-size model showing a tsunami of consumer goods (Arles, Rhone River) 2.3 The ‘cultural revolution’ The Augustan principate accelerated a cultural transformation or ‘metamorphosis’ in Rome and the provinces that had begun in the late Republican period.24 Developments in public monumental architecture, poetry, literature, religion and of course, leisure or otium reflected a ‘quite startling’25 phenomenon. Imperial building projects such as the fora of Julius Caesar and Augustus provided models for provincials to emulate. Why did the Gallic elite enthusiastically adopt and adapt Roman culture from the late 1st century BC? Like their Roman patrician benefactors, the new Gallic elite pampered their followers; consequently, the two social/political systems meshed together well. Conspicuous consumption was the order of the day! ‘Bread and circuses’ or euergetism (benevolent, communal gift-giving) became fashionable. Opportunistic elite Gauls could get ahead especially as towns adopted Roman style constitutions - Roman colonies paid less tax and had more legal rights!26 23 G. Woolf, Ibid. pp.241-242 A. Wallace-Hadrill, Augustan Rome, (London, 2003), pp. 10-11 25 Ibid. p.50 26 G. Woolf, Becoming Roman-the Origins of Provincial Civilization in Gaul, (Cambridge, 2003), pp.223-224 24 A pattern of ‘cultural revolution’ based on euergetism was repeated in many of the sites I visited. In Lyon (Lugdunum) an inscription that was originally located in its amphitheatre is now in Lyon’s Gallo-Roman Museum. The inscription informs the reader that the amphitheatre was dedicated to Tiberius (19 AD) by Gaius Julius Rufus, an elite Gaul from the Santon tribe. Rufus also dedicated a triumphal arch in his tribal civitas or capital (Saintes) to Germanicus. Inscription of Gaius Julius Rufus dated 19 AD (Gallo-Roman Museum, Lyon) CONCLUSION During my ‘grande d'étude de la France’ I was able to clarify the concept of ‘romanisation’. Firstly, I was able to expose the myth of Celtic Gaul, which is perpetuated by the ancient Roman writers, that the Celtic Gauls were ‘barbarians’. In fact, Celtic Gaul laid the foundations of a wealthy Gaul whose wealth grew exponentially within the ‘new age’ of imperial Rome. The Celts of Gaul were formidable artisans, farmers, warriors, merchants, philosophers (the druids) and craftsmen. Secondly, a fresh approach is required in defining the concept of ‘romanisation’. My study tour of France supported Woolf‘s twin revolutionary concepts of massive consumer and cultural change in Gaul driven largely by the elite Gauls but in time shared to some degree by all. The multitude of Gallo-Roman consumer goods and monumental cultural sites on display in French museums and archaeological sites such as Dijon, Bibracte, Chatillon-sur-Seine, Chalon-sur-Saone, Saint Romain-en-Gal, Vienne, Argenton-sur-Creuse, Orange, Lezoux, Clermont-Ferrand and Vaison La Romaine testify to an explosion of wealth as measured in the variety and quantity of consumer goods in addition to the wonderful cultural legacy of theatres, fora, bathhouses, villae, aqueducts and amphitheatres. Finally, I have made available a website for students and teachers to use as a resource at http://www.historyguru.com.au BIBLIOGRAPHY Alcock, S.E.,“Vulgar Romanization and the Dominance of Elites”, in S. Keay and N. Terrenato eds., Italy and the West- Comparative Issues in Romanization, (Oxford, 2001), p.227 Cuncliffe, B., The Ancient Celts, (Oxford, 1999) Crumley, C.L. and Marquardt, W.H. eds. Regional Dynamics: Burgundian Landscapes in Historical Perspective, (San Diego, 1987) Gardner, A., “Fluid Frontiers: Cultural Interaction on the Edge of Empire”, Stanford Journal of Archaeology, vol. 5, 2007 Krausz, S., “The topography and Celtic fortifications of the Bituriges oppidum at Châteaumeillant-Mediolanum (Cher)”, r.a.c.f., Tome 45-46, 2006-2007 Loughton, M.E., “Getting Smashed: The Deposition of amphorae and the drinking of wine in Gaul during the late Iron Age”, Oxford Journal of Archaeology, vol.28 (1) 2009 Siculus, Diodorus, Library of History, (5.26.3) Wallace-Hadrill, A., Augustan Rome, (London, 2003) Wells, P.S., The Barbarians Speak, (Princeton, 1999) Woolf, G., “Beyond Romans and natives”, World Archaeology, Vol. 28(3) 1995 Woolf, G., Becoming Roman-the Origins of Provincial Civilization in Gaul, (Cambridge, 2003)