Chapter 1

advertisement

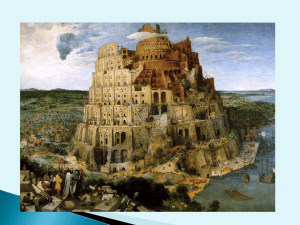

Hejazi Hana / Standard & Non-Standard English/ page 1 Chapter One Standard and Non- Standard English It is important to consider the non- native speakers and learners of English in the world today. Since there are now more non-native speakers of the language, these surely have a right to be heard. What is the role of a teacher if she/he cannot speak for those who cannot speak for themselves? In fact, the real issues of standard /non standard English –which rely heavily on the assumptions related to the general debate about formal properties, educatedness, associated values, and social functions in respect to native speakers, have to be viewed in a special perspective when the context is EFL (English foreign learners) . This chapter provides debates and detailed analysis on the status and functions of standard / non standard, English as viewed and varied from country to country, from writer to writer and from variety to variety. However, for the writers who have been chosen here to speak for themselves and to characterize the definitions or ideas of standardization, Standard English will remain an issue and a debate restricted within national and native speaker areas. So the following established debate among writers supporting or opposing the notion of standard, may seem irrelevant for EFL, since it does not account for the people who are using it and therefore arguments for the most part self-contained in that they are mainly meant to be addressing people who already possess the language. Rather than working on different agendas, we thought, it better to represent the different views and recent approaches which are current among linguists and sociolinguists .This would allow us to follow our assumptions in a manner of trying to allocate EFL in the heart of the debate in terms of standard and non –standard English which has been a marginalized area in this field in so far. Indeed, it will be apparent that the real focus is drawn on the majority of writers who deal with various issues concerning Standard English in Britain. Nevertheless, it would Hejazi Hana / Standard & Non-Standard English/ page 2 have been short sighted to have ignored other important debates, which have taken place, elsewhere in this field such as those which have emerged in the USA. . Although, it is worth noting here, that it would be misleading to suggest that these quotations and different argument suggested by different experts writing on Standard English represent the last words or consensus on the issues they address. For one reason we believe if there is no disagreement , there will be no available agenda for meaningful debate and that their resources might perhaps act as useful pointers to the notion of standard English which might rise from this center to another center of other kinds of debate. The first defining characteristic of standard English, as defined is its ‘generality ‘and ‘uniformity’, the widespread nature of its use all over the world, though there are small differences, between the two main forms of English that are learned internationally; British English and American English. Other forms of English derive from one of these, Canadian and Philippine English, Australian Englishes and the world Englishness of different parts of Africa. All of these varieties have their own regional features in terms of vocabulary and grammar,. The forces which help to maintain the relative uniformity of the growth of English as international language is standardization, and it is quite clear that the power of standard, which can hold the language together, can also drive English world local speakers apart. The development of local varieties of English has been a way of marking out social identities. American English for example has developed considerably over the last two centuries but never enough to overcome other English dialects and achieve independent status. One way of understanding this development is to follow useful classification of different Englishes, see Kachru’s (1985 : 123 )cited in Bex et al ( 1999:4). He distinguishes varieties according to ‘speech fellowship’. His classification correspond to the geographical location of different Englishes and the ways in which their speaker construct notions of correctness’. Kachru describes these ‘fellowships’ as belonging to three concentric circles. The inner circle contains those speakers of English who are native speakers, such as British, American, and Australian. The outer circle Hejazi Hana / Standard & Non-Standard English/ page 3 contains those who learn it as a second language, such as Africa and India, and finally the expanding circle as those who learn it as a foreign language example, European and Far East and Middle East countries. Kachru brings into sharp focus the problems of standard English in terms of regional and national varieties that have developed worldwide. He, therefore, rejects a mono model of English even for pedagogic purposes arguing that : Kachru ( 1985: 123) in Bex et al ( 1999 : 4) ‘ in addition , there are several types of Englishes, for example in South Asia or parts of Africa , which are not meant necessarily for the consumption of a native speaker of English . They have their national or regional functions. On the cline of Englishness these may be low, but functionally they serve the purpose of communication as does another human language.’ A leading Black African academic, Professor Ndebele claimed that the concept of international language is ‘an invention of western imperialism. See Honey ( 1997:256). Standard English is now a battlefield. Despite its fifteenth -century origins, there has been a crucial element in an educations system. There are today people who still question the appropriateness of teaching Standard English in schools. Their reasons is that to promote one form that is , the standard English in schools means a disparagement of non-standard forms , and for this reason discussions about standard and non standard English became somehow an emotional issue. And so the standard English debate rumbles on .Trudgill ( 1974 d) defines Standard English saying It is that variety of English which is usually used in print, and which is normally taught in schools and to non-native speakers learning the language . It is also the variety which is normally spoken by educated people and used in news broadcasts and other similar situations. The difference between standard and non-standard , it should be noted , has nothing in principle to do with differences between formal and Hejazi Hana / Standard & Non-Standard English/ page 4 colloquial language or with concepts such as ‘bad language’. Standard English has colloquial as well as formal variety and standard English speakers swear as much as others.’ Trudgill ( 1974d: 5-6) Honey (1997: 148) also shows the same opinion in that standard English is both a written and a spoken variety . Honey ( 1997: 3) starts his definition about standard language by saying it is a written language , ‘ By Standard English I mean the language in which this book is written’ , he then defines its characteristic as its ‘ uniformity’ , generality and its ‘correctness’ which for the most part , ‘codified , embodied in dictionaries and in set of rules taught in schools , both to children whose native language is English, and to those learning English as a foreign language.’ ( 1997 : 3).As far as speaking is concerned , Honey did not make a clear clarification when saying ‘Standard English can be spoken in any accent’ Honey ( 1997: notes ( 1999:271) ‘ argues ‘ It is an established fact that no language or dialect is superior to another’ . The Milroys interest in differentiating between (spoken and written English) make their work significant in that they pointed out some differences between spoken and written English, such as situational factors, tone of voice, ellipses and so on in respect to standard English . Their brief account that speech is usually spontaneous, whereas writing typically need s preparations and planning leads them to regard the ideology of standardization as ‘disease’ Honey (1997: 131) in that the prescriptive rules derived from written English should be applied to the way spoken English is used . James Milroy argues in (1999: 17) that ‘all languages are variable and not uniform and that the idea that languages can be believed to exist in static invariant forms may well be to a great extent a consequence of the standardization’. In other words the ‘uniform’ state of idealizations is not empirically verifiable. That is to say, if we examine the way people speak Standard English, it will never conform to idealization. James Milroy in (1999: 16) Hejazi Hana / Standard & Non-Standard English/ page 9 . The crux of the debate remains crucial in terms of non-native speakers . Why could not the standard English give the non- native speaker this optional tendency ,even though ‘standard English’ may guarantee to give him the features of ‘educatedness’ ‘correctness’, and high position. Is there something lacking in the standard English which filters everything he has been learning and reduces him to unintelligibility once faced with the greatest challenge , the native speaker .Trudgil says (1999: 123 ) ‘standard English is not a language , is not a style , is not a register , is not an accent . The fact is as he argues that although standard English is so widely used in education, and in the media , the most people in Britain continue to speak non-standard dialects Trudgill ( 1994: 9 ). This final arguments about standard and non- standard is not where we end but where we should start. As far as EFL is concerned, the influence of English is obviously a function of rapidly growing internationalization, but it is important to realize that the process of internalization is no longer the privilege of an educational elite. In fact, the promotion of English for the purpose of international communication English from ‘above’ now has its popular counterpart English from ‘below’ often representing the use of spoken dialects. The suggested theory is on how to make decisions as to how to reconcile these two distinct varieties. Our next chapter will be about native and non-native speakers under the heading ‘language and society’ It goes without saying that non –native English teachers should (in the first place) know at least one variety of non- standard pronunciation and intonation in a certain dialect for teaching. Unfortunately, teachers ‘ positions here are not superior to their non-native learners. Now that the Position of EFL in foreign countries like (the middle east for example) has tremendously changed. English is no more considered to be a ‘ foreign language .It is known and spoken by almost everybody below the age of forty. English is seen in every shop, in every street, on buses and in local and international areas. Children are exposed to English before they enter schools. Pop music and American films have played an important role in promoting the language. Moreover the Internet is used by children at a very young age(6-7). Code switching has become Hejazi Hana / Standard & Non-Standard English/ page 12 normal rather than exceptional. For these reasons and even more, too much emphasis on teaching grammar and rules is becoming ridiculed especially when students are destined to receive what they already know or what they can acquire in a short time. So why then, are we freezing this category in the frame of standard and repeating grammar rules and formal meaning and restricted vocabulary in all the child’s school life? What was ideal in the past is obviously irrelevant in the future and the signs of triviality are clearly present today. It is time to think of new material for teaching a new generation to give them more options in life and motivation to want to learn more about the true language. The task of teaching English to the world is , nowadays firmly in the hands of non-native teachers, and the greatest number of English speakers is emerging from the expanding circle- . Thus it has become our notion to equate teaching the local model as opposed to international of English. This is why we have allowed experts to dispute about the nature and definition of standard and non –standard English. It is time to allow ourselves to speak on behalf of EFL and recommend that they enter such debates . For this to happen, the debate should include and involve all non-native teachers , and learners whose English has already achieved a norm and are ready for further advance .