Lobelia monograph - Foundations In Herbal Medicine

advertisement

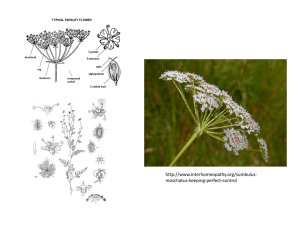

Common Name: Lobelia Botanical Name: Lobelia inflata L. Other species include L. cardinalis L., L. siphilitica L., and L. spicata L. Family: Campanulaceae Other Names: English: German: French: Trade Name: Parts Used: The dried aerial parts are generally used, but some herbalists prefer the fresh tinctured plant. The roots were used by indigenous people as a diuretic. Indian tobacco, Pukeweed Lobelienkraut, Spalglockchen, Indianischer Tabak Lobelie enflee Herba Lobeliae inflatae1 Constituents: Alkaloids (0.2-0.6% total, BP min. 0.25% total calculated as lobeline)2: At least 14 different piperidine alkaloids, principally (-)-lobeline, with lesser amounts of meso-lobelanine, meso-lobelanidine; and the piperideines. These alkaloids are biosynthetically formed from two molecules of phenylalanine and one molecule of lysine.3 Carboxylic acids: chelidonic acid and beta-beta-phenyloxyproprionic acid. Actions: Parasympathomimetic Respiratory stimulant Emetic Expectorant Anti-spasmodic Sialagogue Diuretic Anthelmintic Historical Note: Lobelia grows throughout much of the United States but much of the written literature on this plant is from the colonial period of the east coast. While the Penobscots and other Eastern indigenous peoples used L. inflata as an expectorant and emetic to clear the stomach before “their great councils,” other species of Lobelia were used far more often. L. siphilitica was so named because the Iriquois peoples believed the root to be a cure for syphilis. While the efficacy of this root to cure syphilis remained in great debate in the early 1800’s, a number of practitioners found it effective for the treatment of gonorrhea, and it was a popular diuretic. L. Copyright Tieraona Low Dog, MD 2008. cardinalis was used by many tribes as an anthelmintic, its actions similar to L. inflata but weaker. L. inflata was used for the treatment of asthma, bronchitis, pneumonia, angina, as an emetic, and colic. The leaves were often smoked for the relief of asthma. Samuel Thompson encouraged the use of lobelia for the treatment of asthma and bronchitis and as an antispasmodic and anti-convulsive. Popularity grew in spite of reported poisonings. The dried leaves and tops were official in the USP for their emetic and expectorant properties (1820-1936) and in the NF (19361960).4 Pharmacology: Structurally and pharmacologically, lobeline is similar to nicotine but less potent. Lobeline has both stimulant and depressant phases of action. Because lobeline effects so many systems in the body, it is probably simpler to break it down by body system. Cardiovascular System: at low doses, the release of epinephrine and norepinephrine by the adrenal medulla, stimulates the heart rate and mildly elevates blood pressure. This results from activation of both the aortic and carotid chemoreceptors, leading to tachycardia and vasoconstriction with a subsequent rise in systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Gastrointestinal Tract: in general, via stimulation of the parasympathetic nervous system, gastric acid production is increased, while bowel tone and peristalsis is enhanced. Occasionally, diarrhea is encountered from the ingestion of excessive amounts of lobelia. The vomiting that occurs from the ingestion of lobelia is the result of both central and peripheral actions. The alkaloids stimulate the area postrema of the medulla oblongata, better known as the “vomiting center.” Lobeline also stimulates both vagal and spinal nerves, which are part of the reflex pathway of vomiting. The name “pukeweed” is quite an appropriate term. Peripheral Nervous System: lobeline transiently stimulates and then depresses almost all autonomic ganglia. Small doses of lobelia directly stimulate the ganglia and enhance nerve transmission. Larger doses stimulate the ganglion cell, quickly followed by a blockade of nerve transmission. Small doses of lobelia stimulate the adrenal medulla to release epinephrine (adrenalin), while larger doses inhibit the release of epinephrine due to stimulation of the splanchnic nerves. Lobeline stimulates a number of sensory receptors; the stretch and pressure sensitive mechanoreceptors of the tongue, skin, lung, and stomach; the chemoreceptors of the carotid body; pain receptors and the thermal receptors of both the skin and tongue. Central Nervous System: small doses stimulate the CNS. Larger doses, can cause tremors and convulsions. In very large doses, if emesis does not clear the alkaloid, depression of the CNS occurs and death can result from respiratory failure secondary to both central depression and peripheral blockade of respiratory musculature.5 Respiratory System: lobeline initially causes a mild increase in salivation and bronchial secretions, then has an inhibitory action. Small doses of lobelia cause excitation of the respiratory tract reflexly through stimulation of the chemoreceptors in the carotid and aortic bodies. Large doses cause respiratory depression as mentioned in the previous paragraph. Stimulation of adrenal catecholamines causes -adrenergic bronchodilator. Applications: Respiratory: Lobelia is still used by herbalists in the treatment of asthma and chronic bronchitis. Those with copious mucus production but difficulty removing it (i.e., emphysema, chronic bronchitis), find that lobelia reduces secretions while helping expectoration. Lobelia is of benefit in cases of pneumonia when there is a subjective feeling of “weight” on the chest and an inability to take a deep breath.6 Spasmodic asthma responds quite well to the plant when taken properly. Small doses initially cause expectoration, which is then followed by relaxation of the bronchioles and easing of the cough. The herb may be used in small daily doses to keep the lungs free from excessive accumulation of secretions in those with emphysema. In cystic fibrosis, there is a marked increase in the production of pulmonary secretions, the sputum often being quite viscous and purulent. Lobelia is an excellent choice for this population because of its ability to assist in expectoration. Chronic bronchitis, defined as excessive tracheo-bronchial mucus production sufficient to cause cough with expectoration, is quite prevalent in the United States. This is largely the result of tobacco smoking, increased air pollution and occupations that expose their workers to organic/inorganic dusts, or noxious gases. Inflammation of the small airways and hyperplasia of the mucus-producing glands in the large airways are characteristic of the disease. Lobelia, along with licorice and ginkgo, is beneficial in keeping the lungs free from excessive mucus helping to reduce infection. Gastrointestinal. Lobelia effectively increases secretions and motility of the stomach and bowel. Significant amounts of gastric mucus are produced which may be a result of gastric irritation. Taking lobelia with an herb such as chamomile or licorice is probably wise to protect the gut. Appetite is stimulated, flatulence reduced, and digestion enhanced with small doses of lobelia. The aerial parts of the plant enhance exocrine secretion from the pancreas, thus aiding in the digestion of starches, proteins, and fats. Lobelia combines quite nicely with the anthraquinone Copyright Tieraona Low Dog, MD 2008. containing laxatives to overcome habitual constipation. Peristalsis is enhanced, while griping can occur with stronger cathartics. Lobelia may be considered in cases of spastic colon. Reproductive. Lobelia is sometimes employed by midwives during early labor to relax a thick and rigid os. With oral ingestion, lobelia relaxes the perineal muscles, easing a difficult labor. Nervous & Muscular Systems Lobelia is a useful anti-spasmodic. The British Herbal Compendium recognizes lobelia for the treatment of spastic muscle conditions. Lobelia may be considered when there is spasticity or muscular rigidity, i.e.; the spasticity that can accompany multiple sclerosis; myoclonus, and some of the dystonias. When lobelia is combined with capsicum, the resulting liniment is very effective when applied topically for neuralgia, easing the pain from bruising, sprains and strains; easing muscle spasm, and reducing muscle fasciculation. The herb is occasionally combined with valerian and cramp bark for the relief of tension headaches. Urinary system. Lobelia may be useful in some cases of hyper-reflexic bladder; complaints such as incontinence, urgency and frequency are common. Lobelia has a mild contractile effect on the urinary bladder. The roots of all species of lobelia have substantial diuretic properties. Pharmacokinetics: Lobelia is well absorbed from mucous membranes of the mouth, gastrointestinal and respiratory systems. Lobeline is metabolized primarily by the liver, kidney, and lung, with rapid excretion by the kidneys.7 The rate of excretion is enhanced with acidic urine and diminished by alkaline urine. Thus, vegetarians may be slower to eliminate the alkaloids present in the plant and more at risk to adverse effects. Drug Interactions: Caution should be exercised when using lobelia with other strong muscle relaxants or central nervous system depressants. Lobelia binds nicotinic receptors and should be used with caution in patients receiving nicotine therapies for tobacco withdrawal. Toxicology: Overdose of Lobelia can cause severe adverse effects including vomiting, profuse sweating, muscular paralysis, tachycardia, hypotension, respiratory failure secondary to respiratory muscle paralysis, coma and death. Fatalities have been recorded from overdose of this plant. On EKG, one will see extrasystole, sinus arrhythmia and bundle branch block. For overdose: treatment consists of emesis (which usually occurs naturally with overdose); activated charcoal and purgatives should be given. In severe overdose, atropine 2 mg. subcutaneously, warming blankets, and dopamine is indicated if the individual is hypotensive. A ventilator may be necessary if respiratory paralysis occurs. Side Effects: Nausea is the most common side effect reported by individuals. Other side effects include coughing, dizziness, increased blood pressure, heartburn, and diaphoresis. Contra-Indications: Lobelia should not be used by nursing mothers as the alkaloids are excreted in breast milk. Lobelia should not be used by those with rapid evacuation of bowels, hypersecretion of stomach acid, tendency towards ulcers, etc. Should not be used by those with impaired mental cognition who may be at a higher risk of aspiration and unable to communicate when they are feeling nauseated. Lobelia should be used cautiously in those with hepatic or renal impairment. Dose: A significant problem in using lobelia is the lack of standardized preparations for internal use. Considering the potential toxicity of the alkaloids, this can make lobelia a potentially dangerous plant for use by an uneducated public. The following tincture dosage is from the BPC of 1973. Tincture of dried aerial parts - 1:5 with 60% alcohol Adults: 0.3 ml - 1 ml. TID8 Children: calculated for age and weight. Always start at the low end of dosage range and titrate upwards as needed. Dried herb: 50-200 mg. in infusion TID. Author’s Notes: While there is undoubtedly risk from toxic doses of the plant, in the hands of a skilled practitioner, lobelia makes a useful addition to herbal combinations for spastic colon, chronic bronchitis, and muscle spasticity. However, because of its potential toxicity, this is not an herb I recommend for general use by the public. Copyright Tieraona Low Dog, MD 2008. 1 Steinmetz, E.F. Codex Vegetabilis Entry number 670. Self-published, 1957. British Herbal Compendium Volume 1. Bradley, P. Ed. British Herbal Medicine Association, Dorset, 1992. 3 Bruneton J. Pharmacognosy, Phytochemistry, Medicinal Plants. Lavoisier Publishing, Paris, 1995. Pages 695-96. 4 Vogel V. American Indian Medicine. Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma, 1970. Pages 330-32. 5 Damaj MI, et al. Pharmacology of lobeline, a nicotine receptor ligand. J Pharm Exp Ther 1997; 282:410-19. 6 Felter HW, Lloyd JU. King’s American Dispensary. Eclectic Medical Publications, Portland, Oregon, 1983. Pages 1199-1205. Original publication 1898. 7 Westfall TC, Meldrum MJ. “Ganglionic Blocking Agents” in Craig CR, Stizel RE. Modern Pharmacology 2nd Ed. Little, Brown and Company, Boston, 1986. 8 British Herbal Compendium Vol. 1. Bradley, Peter Ed. British Herbal Medicine Association, Dorset, 1992. Pages 149-50. 2