MYSTICISM AND UTOPIA: - Gurdjieff

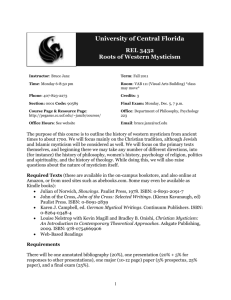

advertisement