Review of Andrew Newman`s The Correspondence Theory of Truth

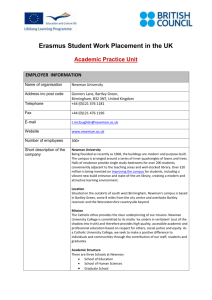

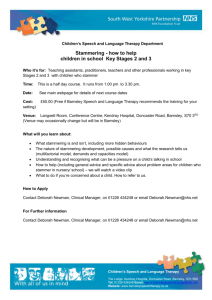

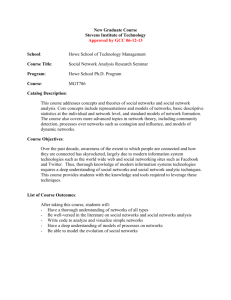

advertisement

Review of Andrew Newman’s The Correspondence Theory of Truth: An Essay on the Metaphysics of Predication In his recent book, Andrew Newman provides a detailed examination of the correspondence theory of truth and related issues, including the nature and status of truthbearers (especially beliefs and propositions), of facts, and of correspondence. It is a virtue of the book that these issues are examined in considerable depth, with appreciation for both the history of analytic metaphysics and current work in the field. Realism about universals is central to Newman’s project, and thus his first chapter is devoted to the realism/nominalism debate. The principal point raised against nominalism is that it cannot make sense of what is said when we say that a particular possesses a property. (17). Newman appeals to Armstrong’s familiar arguments against candidate analyses of class, predicate, and resemblance nominalisms. Adding a rather poor one of his own, he tells us that a predicate “F”’s being true of a particular a differs very little from the sentence “Fa” being true, so that to explain the truth of “Fa” in terms of ‘”F” being true of a is to give a circular explanation (28). However, “F”’s being true of a is equivalent to “Fa” being true only on the false assumption that ‘a’ necessarily refers to a. Moreover, many nominalists today would give a deflationary explanation of being true of: “F” is true of a, if it is, because, a is F. This account may be inadequate, but it is not circular. In his second chapter, Newman rejects Paul Horwich’s minimalism on the ground that the T-schema instances cannot explain the correspondence conditions of various truth-bearers. The explanation won’t work because the T-schema instances are platitudinous and apply to all members of a type of proposition, while the correspondence conditions lack both these features. (36) There are several problems here. First, if sound, this reasoning would seem to cut both ways, making trouble for the correspondence theory: how could correspondence conditions explain T-schema instances? Second, minimalist explanations of facts about truth standardly appeal, not merely to the Tschema, but to auxiliary theories and facts that do not involve truth. Of course, platitudinous premises, when conjoined with non-platitudinous premises, can yield nonplatitudinous conclusions, and inferential chains of platitudinous connections can yield non-platitudinous conclusions. These auxiliary premises may also apply only to a type of proposition. Third, a deflationist (if not Horwich himself) might well dispute whether anything further is needed to account for correspondence than the likes of “<Fa> is true, if it is, because Fa”. Newman’s own preferred theory of truth, articulated in chapter 3, is correspondence “without facts.” In essence, a predicative sentence is true iff “the particulars referred to by the proper names in the sentence actually instantiate the universal referred to by the predicate in the sentence.” (76). Correspondence for complex sentences is then understood in terms of correspondence for predicative sentences. According to Newman, instantiation is not a “real relation,” because it involves an unsaturated entity’s combining with saturated entities. Bradley’s regress is therefore blocked. (25-6) There are difficulties here. First, Newman’s commitment to the Eleactic principle, viz. that what’s real possesses or contributes to the possession of causal powers (51), ought to make him recognize instantiation as real, because the fact that a person, say, instantiates a certain weight property can contribute to her causal powers. Second, a saturated entity (e.g., a person) and an unsaturated entity (e.g., blueness) can both exist without the former instantiating the latter. That is to say: instantiation is not in general internal. If it is external, though, aren’t sentences like ‘a has F-ness’ predicative? And if they are, won’t their truth require a second-order instantiation relation? One would like to say: if a instantiates F-ness, that is because a is F. But this deflationist move is not available to Newman, who wants to reverse the order of explanation. Newman’s response to worries about instantiation is to point out that some things must combine, because otherwise there would not be wholes at all (26). However, even if instantiation is a kind of combination, composition through instantiation clearly faces problems not faced by other modes of composition. Thus, e.g., extensional mereological and set-theoretic “composition” satisfy the principle that sameness of constituents entails sameness of composites. Moreover, the response is in direct conflict with a nice point in Newman’s discussion of facts, viz. that because not every relation generates a composite of the things related, we should not expect there to be a composite, a fact, when a particular instantiates a universal. (148) The centerpiece of the book is the explanation and defense of Russell’s “multiple relation” theory of (simple predicative) belief in chapters 4 and 5. The theory in question holds that belief is not a dyadic relation between persons and propositions but rather a multiple relation between a person and a number of terms, including a distinguished universal. Thus, Othello’s believing that Desdemona loves Cassio consists in belief holding between Othello, Desdemona, Cassio, and loving. As Russell pointed out, a distinct advantage of this theory is avoidance of “false objectives,” i.e., false facts or independently existing false propositions. Given the theory, a correspondence theory of truth can be formulated thus: a predicative belief is true when its object terms are related by its relation term, and false when they are not so related. Newman identifies three main problems for Russell’s theory. (1) the direction problem (explaining how S’s believing that aRb is distinct from S’s believing that bRa); (2) the problem of the twofold role of the relation (as a “relating relation” or as an “abstract term”); and (3) the problem of the unity of belief (the sense in which the terms count collectively as “something believed”). To his credit, Newman realizes that Russell’s account inherits many of the difficulties of direct reference accounts. To answer the objections, he turns to Nathan Salmon’s work. He also realizes the significant challenge facing the Russellian of explaining the nature of non-predicative belief. On the direction problem, Newman follows Russell’s 1912 solution (belief, like other relations, has a “sense,” an order). He claims problem (2) collapses into problem (3), because it is not as if “abstract” and “relating” relations are different kinds of entity; relations may exist whether or not they relate a particular pair. (96) The challenge is to explain the special role of the relation term, for if its role were no different than the other terms’, then, as Wittgenstein emphasized, all varieties of nonsensical judgments would be possible (“S judges that Bush Cheney”). One of Newman’s notable contributions is his “formal hypothesis” about the binding together of the various terms in the judgment relation. This hypothesis states that “Believes (S, a, b, R) should be analyzed as (S)BelievesR(a)(b), “where the universal R bonds first with the propositional attitude “Believes” to give a three-place relation, namely, ( )BelievesR( )( ), which is then capable of bonding with three particulars, one of which is the subject.” (112). Informally, the idea is that (predicative) belief involves believing a universal of objects. Newman takes his hypothesis to reveal a crucial difference between the role of the relation term and the other terms. In belief, the relation term is “how the person thinks of the particulars.” (116). The object terms are merely thought about. (Side issue: one wonders how beliefs can be true for Newman, since beliefs, for Russell, are facts, and Newman rejects facts.) Most realists will go along with the idea that universals may combine in certain ways to form other universals. What Newman wants to convince us of is that, e.g., belief can combine with loving to yield a ternary relation believes loves. Unfortunately, his explanations are not of much help. We’re told that a propositional attitude is unsaturated in two different ways: “at the front end it is unsaturated in the usual way with an empty place that requires a particular to fill it; at the other end it is unsaturated in a different way, with an empty place that requires a universal to fill it.” (113). This cannot be analogized with the more familiar kinds of composition of universals: molecular logical composition, that of structural universals, of relational properties from relations, of “adverbial” universals. One worries that Newman is asking us to accept an additional primitive kind of composition of universals, merely to save Russell’s theory of belief. Although Russell’s theory does not take propositions as the objects of belief, Newman accepts propositions. Based on an interpretation of Russell’s remarks about propositions in “Logical Atomism,” he takes propositions to be mind-dependent entities. They are “units” because we can think about them (and not merely think them). (122). They are “real units” because they are units and have real components. (128). It is hard to follow Newman here. Can’t we think about facts? Don’t they have real components? Yet, we are told they are not real units. In any case, propositions are “abstracted” from particular belief contexts and depend on such contexts for their existence. (123). It is not clear what such abstraction involves other than a brute necessary connection between a proposition and there being a subject with the relevant belief. Newman speaks of propositions being “immanent.” This suggests an analogy with universals. Like universals, they occur in many contexts (e.g., we believe the same proposition in thinking that Bush is president). (195) This analogy, as Newman is aware, is limited in at least two ways. First, propositions are not characteristics of believers, while universals are characteristics of what they instantiate. Second, universals exist only it they are true of some object or other, whereas propositions can exist even if false, so long as they are believed. Here I must ask: wasn’t the main point of defending Russell’s theory of belief that it obviated the need for “false objectives”? If false propositions were wholly mental, that would perhaps ease concerns about them; but, for Newman, they consist of all and only real and (typically) mindindependent constituents, which makes it hard to regard them as wholly mental. The instantiation requirement on propositions – their immanence – creates a host of other problems. It compromises the utility of the truth-predicate over propositions, because there will be numerous and varied counterexamples to the truth schema for propositions: the proposition that p is true iff p. It also makes it difficult to know if a perfectly meaningful sentence expresses a proposition. While there is a proposition that p, there may well not be a proposition that not-p; and, while there are propositions that p and that q, there may well not be a proposition that p or q, etc. Newman’s book includes numerous fair and careful discussions of others’ work. I refer the interested reader particularly to the discussion of Platonist theories of propositions (chapter 7) and the criticism of Armstrong’s claim that instantiation and states of affairs are one and the same (145). Although I have criticized the main arguments of the book, I recommend it as a useful resource for analytic metaphysicians.