analysis-of-syntax transcript

advertisement

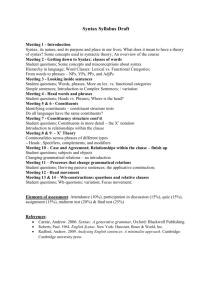

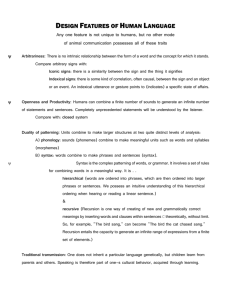

Transcript for AP Language Analysis of Diction, Syntax, and Organization: Emphasis on Syntax Hello, and welcome to the fourth podcast in a series to prepare AP Language students for the AP Language test. Thanks for tuning into this podcast; I hope this information will help you do that much better on the AP exam. I would like to give credit to the Encarta Online Dictionary for some definitions, the Textbook Everyday Use, from which I pull several examples that I would like to discuss. So let’s talk about analysis. In the last podcast, we discussed the differences between a rhetorical and literary analysis, and then we focused on choices in diction. For this podcast, I would like to take a closer look at syntax, or “the ordering of and relationship between the words and other structural elements in phrases and sentences. The syntax may be of a whole language, a single phrase or sentence, or of an individual speaker” (Encarta Dictionary). A writer or speaker might have the most profound thought, but if he cannot put that thought on paper in a concise manner, the words become useless. Consider the following: Am I therefore think I. Doesn’t make much sense, does it? How about this one? Therefore, I think I am. This seems to make some sense, but we would need some kind of context in which to place the sentence in order for those five words to be significant. How about this one: I think; therefore I am. A Ha! Now I have a profound statement first coined by Rene Descartes. This one sentence morphed into an entire school of philosophical thought, but when you rearrange the words (like the first example of Am I therefore think I) you have nothing. So why am I telling you this? Because the order in which you place your words matters! When you analyze prose, you not only want to look at the meaning of the words, but where the author chose to place those words. So let’s talk about sentence structure. As you know, there are several kinds of sentences: Simple, compound, complex, and compound-complex. But Why should you be concerned with whether a sentence is simple, compound, complex, or compound-complex when you are analyzing someone else’s writing or planning your own? Because Function grows out of form. When you need to make a succinct point, often a short, simple sentence will do so effectively. A simple sentence also fits well after a group of longer sentences, and can signal a transition or the author’s desire for the reader to stop and pause for a second. A short, simple sentence can suggest to a reader that you are in control - that you want to make a strong point. Consider the following example: Princess Leia: [in a holo message] General Kenobi: Years ago, you served my father in the Clone Wars; now he begs you to help him in his struggle against the Empire. I regret that I am unable to present my father's request to you in person; but my ship has fallen under attack and I'm afraid my mission to bring you to Alderaan has failed. I've placed information vital to the survival of the rebellion into the memory systems of this R2 unit. My father will know how to retrieve it. You must see this droid safely delivered to him on Alderaan. This is our most desperate hour. Help me, Obi-Wan Kenobi; you're my only hope. In the paragraph above, Princess Leia, in the form of a holo message, appeals to Obi Wan to help her. She begins with a couple compound sentences with demonstrate complex political and social issues on the planet of Alderaan and with the Empire. After she explains the background, she gets her true message across, in which she gives specific instructions, through the use of simple sentences. When speaking about the vital intelligence necessary for the survival of the rebellion, she says: My father will know how to retrieve it. You must see this droid safely delivered to him on Alderaan. This is our most desperate hour. The princess wants Obi Wan to know, without a doubt, that this is it. He must help them. If she had placed these sentences deep within complex structures, perhaps the general would not have realized how serious the situation was. Why might you use a compound sentence in your writing? If you are trying to show how ideas are balanced and related in terms of equal importance, a compound sentence can convey that to the reader. Several compound sentences in a row can tell the reader that you are the kind of person who takes a balanced view of challenging issues. If you have a particularly complex idea, then you might write it with a complex or compoundcomplex sentence. Consider the following scenario, in which I use a colon, a semi-colon, dashes, and then a simple sentence after the complex one to bring my point home. I then use an intentional fragment in a new paragraph to make the most painful point. You might want to look at the transcript for this one: I didn’t know what to do: my boyfriend was with another girl, and it was obvious that they’d been together more than once; I could see the old, familiar look of adoration – that look that he used to give me – on his face. He was in love. But not with me. Relationships are complex, and when you add infidelity to the mix, they become even more complicated. My extensive use of dashes, colons, and semi-colons might seem like too much, but maybe the persona in the piece is feeling overwhelmed. Maybe I want to get that across with my syntactical choices. The final simple sentence “He was in love” pulls together the complexity of the persona’s observations and sums everything up. The intentional fragment accentuates the persona’s pain. Let’s say that you were writing a rhetorical analysis on an excerpt, and you wanted to analyze the syntax. Your first step should be to notice patterns: what kind of sentences are usual, and what sentences stand out? Is there a pattern there? Once you identify what is on the page, you can figure out why it is there. And if you have already identified the choice in diction and the effect those words have on the meaning, you will have clues that will help you in your analysis of syntax. Of course, when writing about syntax you can choose to focus on punctuation, sentence structure, or figures in which the sentence structure is manipulated for a certain effect (like antimetabole, anaphora, etc.). So how do you know what to focus on? Your best bet is to look for what stands out to you first; after all, you only have 40 minutes to write your rhetorical analysis essay, and so you might have about 4 minutes to read the essay and take note of the rhetorical devices used, diction, syntax, organization, and overall tone and meaning. Bottom line when analyzing syntax: if you notice it first, focus on it and write about it. Obviously this is what the writer wanted you, the reader, to see. The most important thing you have to remember is that every aspect of syntax – every comma, dash, exclamation point, and period – was a careful choice made by the writer. You have to identify the choice and the effect of that choice. So here is the first lesson on syntax. There is so much more, so be sure to tune in to my next podcasts.