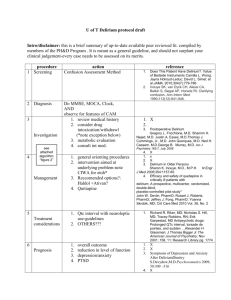

Delirium - overview

advertisement

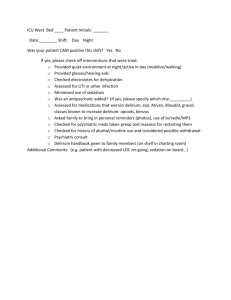

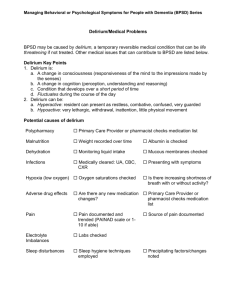

http://www.icudelirium.org/delirium/ Vanderbilt University Medical Center Veterans Affairs TN Valley Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (GRECC) Delirium Overview We hope that this website will serve as a valuable resource for both medical and lay readers interested in learning about delirium in critically ill patients, neurological monitoring instruments for use in the hospital setting, newly recommended patient-oriented (goal-directed) sedation practices, and the under-recognized problem of long-term cognitive impairment following critical illness. In addition to overview narratives, the website provides many training materials and resources for well-validated neurological monitoring instruments including the Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU (CAM-ICU) and the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS), the CAM-ICU Training Manual PDF, frequently asked questions (FAQs) PDF, a printable Pocket Card for medical personnel use, instructional videos, and a list of links to selected references from the peer reviewed literature. We believe that increased awareness and monitoring of delirium and improvements in the delivery of potent psychoactive medications including analgesics and sedatives will lead to better care of critically ill patients and ultimately improve patient outcomes. Terminology: Over 25 different terms have been used to describe the spectrum of cognitive impairment in the ICU including: ICU psychosis, ICU syndrome, acute confusional state, septic encephalopathy and acute brain failure. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM IV) officially defines delirium as a disturbance of consciousness with inattention accompanied by a change in cognition or perceptual disturbance that develops over a short period of time (hours to days) and fluctuates over time. The three motoric subtypes of delirium are hyperactive, hypoactive, and mixed. Medical and nursing literature often refers to patients with hyperactive delirium as having ICU psychosis. The neurology literature generally uses the term “delirium” to refer almost exclusively to hyperactive patients and “acute encephalopathy” as a synonym for hypoactive delirium. We recognize that patients in the ICU develop the spectrum of 3 delirious states (hyper, hypo, and mixed). For general purposes within this website, we will use the term “delirium” to indicate the spectrum of these states and will make distinctions between these motoric subtypes whenever possible with regard to etiology, clinical outcome, and treatment. Etiology: Most patients with delirium in the ICU likely have multiple causes, though these causes are often very difficult to determine with clinical precision. In fact, in our past work, we have determined that on average, ICU patients have greater than 10 risk factors for delirium which places them at a very high risk for this complication. The exact pathophysiological mechanisms involved in the development and progression of delirium are a point of controversy. However, these mechanisms are thought to be related both to (a) anatomic deficits and (b) imbalances in the neurotransmitters which modulate the control of cognitive function, behavior and mood. We will elaborate very briefly on these two categories of mechanism. (a) Anatomic Deficits: Higher cortical areas of the brain such as the prefrontal and non-dominant posterior parietal regions are implicated by CT/MRI or SPECT scans in delirium. Other regions touted as important in such studies include the anterior thalamus, basal ganglia, and the temporal-occipital cortex. A nice review of this work is found in Trzepacz P, Sem Clin Neuropsychiatry 2000;5: 132-48. (b) Neurotransmitter Imbalance: Derangements in levels of serotonin, acetylcholine deficiency and dopamine excess (to name 3) are thought to contribute to delirium, but there are many other neurotransmitters that may be involved. Such derangements could be secondary to a number of causal factors that include reduction in cerebral metabolism, primary intracranial disease, systemic diseases, secondary infection of the brain, exogenous toxic agents, withdrawal from substances of abuse such as alcohol or sedative-hypnotics agents, hypoxemia and metabolic disturbances, and the administration of psychoactive medications such as benzodiazepines and narcotics. A recent study from our group (Pandharipande P et al, Anesthesiology. 2006;104:21-26) documented, for example, that three important risk factors for transitioning to delirium were patient age (FIGURE 2), severity of illness (FIGURE 3), and the administered dose of the sedative lorazepam (FIGURE 1). It is important to emphasize that these data should not indicate a need to avoid lorazepam, as it has an important role in the management of ICU patients, and it is also true that other sedative and analgesic medications are deliriogenic as well. We would emphasize, however, that avoiding the use of any more of these medications than is absolutely necessary is likely an area of focus that may reduce either the onset or duration of delirium. This is a point of ongoing study in the medical field. Prevalence and Clinical Relevance: Critically ill patients are at great risk for the development of delirium in the ICU. With more than 8 out of 10 ventilated patients experiencing delirium, this is one of the most frequent forms of organ dysfunction experienced by critically ill patients. Despite this prevalence, delirium (usually in the hypoactive state) remains unrecognized in 66% to 84% of patients whether they be in the ICU, hospital ward, or emergency department. Delirium in the non-ICU setting has repeatedly been associated with prolonged hospital stay, medical complications that can increase mortality, greater dependency of care on discharge, and higher nursing home disposition rates. In medical and coronary ICU patients, delirium has been reported to be an independent predictor of prolonged ICU and hospital lengths of stay, as well as a higher 6 month mortality rates. Importantly these findings were present even after adjusting for age, gender, race and severity of illness. Delirium may also predispose ICU survivors to prolonged neuropsychological deficits. Delirium Monitoring: The Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU (CAM-ICU) is a valid and reliable serial assessment tool for monitoring delirium in both ventilated and nonventilated ICU patients. The CAM-ICU is easy to use and takes less than 2 minutes to complete. (For more information see the links to the left) Inattention, which can be readily assessed using the CAM-ICU, is the hallmark and pivotal feature of delirium. Remember, delirium is an acquired brain disorder, and should be thought of as a form of organ dysfunction much like low-grade shock or hypoxemia are considered organ dysfunction for the cardiovascular or pulmonary systems. Inattention is a core symptom by which to recognize this form of organ dysfunction in an arousable patient. What is Delirium? Delirium is basically confusion that comes on very fast, sometimes in just a few hours. When someone becomes delirious, it means that they can not think clearly, have trouble paying attention and are not aware of what is going on around them. Sometimes they may even see or hear things that are not really there, but seems very real to them. Is delirium the same as dementia? Unlike delirium, dementia comes on gradually, over months or even years. In most cases dementia is a permanent condition, while delirium usually clears up after a few days to weeks. What could have caused this? • Medications or abused drugs • Poisons • Drug or alcohol withdrawal • Medical illnesses like infections or diabetes • Medical Procedures like surgery • Mental illnesses • Severe pain • Prolonged lack of sleep Can anything be done about it? The doctor and rest of the medical team will try to identify anything that may be causing the delirium or making it worse. They may want to give less or different medicines, wake them up everyday, and treat conditions that could be causing the delirium, like infection. Is there anything I can do about it? The best thing that you can do to help is to work together with your loved one’s nurses and doctors. Provide doctors and nurses with information regarding any time your loved one has been confused because of illness or medications in the past. Help to reorient him or her often regarding the date, time, where he/she is and why, and so on. If your loved one is experiencing agitated delirium, the doctors and nurses might ask you to sit with your loved ones and help calm them down. They might also ask you to help provide a good sleeping environment for your loved one. If your loved one wears glasses or hearing aids, bring them to the hospital so that he or she can use them. It is also very important to be open and honest with your doctors and nurses regarding any behaviors that you notice in your loved one – even after you leave the hospital. Are there any long-term problems that delirium can cause? We don’t know. Ongoing studies are being done to answer this question. Delirium is traditionally considered to be a transient problem that resolves once the cause is removed and the person gets better, however, there is increasing evidence that some patients do develop a dementia-like thinking problem. It is really too early in this area of medicine to know for sure. The return home: what to expect There are many issues to address during recovery from critical illness. While you may do quite well and have a very steady recovery process, you might also be one of the common folks who really has a bunch of issues that need to be addressed before you can really get back to your normal self. Tackling all of these issues is not possible or the intention of this website, but we think it is important to help you at least get a feel for what you (or your loved one) may be dealing with for the next weeks and months. When you do return home, you may feel physically weak, have difficulty thinking, or even have times when you get nervous by remembering events that occurred in the ICU. You need to know that it is not weird or strange for you to experience these types of bothersome feelings. Obviously some people have more trouble with these symptoms than others. Since this website is mainly focused on things about how you “think,” we’d like to say that you might find yourself being more forgetful than before the ICU stay. Some people have difficulty balancing their checkbooks or planning a meal or going shopping. Sometimes it’s hard to go right back to work because you can’t concentrate or have trouble juggling all the tasks that used to be so easy. You may even be more irritable or depressed. People who experience these difficulties often get frustrated or upset by them and this may spill over to the family as well. It is important to talk to your family and your doctor about these issues. Some people get therapy, different types of physical and even “cognitive” rehabilitation after they survive the ICU. Others start on medications depending on the main problems and how long they are lasting. The good news is that most of these problems will go away over the next few months to a year, though in some they can last longer. Delirium Assessment The 2002 clinical practice guidelines of the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) for the sustained use of analgesics and sedatives are geared toward the maintenance of optimal comfort in critically ill patients by focusing on 3 central components - pain, anxiety and delirium. The third component of these guidelines, delirium, is an independent predictor of death, length of stay, cost, and cognitive outcomes at discharge. Although, it is experienced by 60-80% of mechanically ventilated patients, it remains unrecognized in 66% to 84% of patients. The SCCM guidelines recommended that the emergence and/or persistence of delirium be regularly monitored in critically ill patients. The Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU (CAM-ICU) is a delirium monitoring instrument for ICU patients. The CAM-ICU was adapted for use in nonverbal ICU patients from the original Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) (Inouye, Ann Intern Med 1990). The CAM-ICU is a well validated delirium assessment scale that is widely used and easy to administer. It was shown to be reliable and valid in 2 investigations using geriatric-psychiatric DSM-IV ratings in over 750 patient observations (Ely, JAMA 2001 and Ely, Crit Car Med 2001). It performs well even among difficult patient populations (i.e. patients with suspected dementia, patients over 65 years old, and those with very high severity of illness). The CAM-ICU was designed to be a serial assessment tool for use by bedside clinicians (e.g. nurses, physicians, etc). Thus it is easy to use, taking less than 2 minutes to complete and requiring minimal training. Delirium Treatment The most important step in delirium management is early recognition. If delirium is not diagnosed, it is doubtful that any efforts will be made to reverse it. Once delirium is detected, efforts should focus on identifying the etiology. Often this can be done by assessing for the presence of known risk factors. Both prevention and treatment should focus on the minimization and/or elimination of predisposing and precipitating factors. The theoretical goals of management are to improve the patient’s cognitive status and reduce the risk of adverse outcomes such as aspiration, prolonged immobility, increased length of acute care, institutionalization, and death. Delirium Management Protocol Protocols and evidence-based strategies for prevention and treatment of delirium will no doubt emerge as more evidence becomes available from ongoing randomized clinical trials of both nonpharmacological and pharmacological strategies. Our group has deliberately put off publishing a delirium management algorithm because it would necessitates incorporation of “expert opinion” and thus aspects that have yet to be adequately tested or proven. However, the requests for such an approach continue to flood our experiences at national and international forums and numerous emails we receive from website visitors. Therefore, we have developed the following Sedation and Delirium Management Protocol, which basically and succinctly summarizes our approach at the current time. We want to emphasize that this approach, which is largely based on the current SCCM Clinical Practice Guidelines, (VUMC Sedation Protocol) is one which needs to be updated regularly with new data and also personalized at each medical center according to thought leaders at that center. This is not a “one-shoe-fits-all” protocol. We hope that this draft protocol helps you form your own integrated approach to CNS monitoring, sedation targeting, and delirium management in critically ill ICU patients. Nonpharmacologic Primary prevention is preferred; however, some degree of delirium is inevitable in the ICU. Although there are no data on primary prevention (nonpharmacologic) trials in the ICU, the data in non-ICU settings focuses on minimizing risk factors. The strategies include the following interventions: repeated reorientation of patients, provisions of cognitively stimulating activities for the patients multiple times a day, a nonpharmacological sleep protocol, early mobilization activities, range of motion exercises, timely removal of catheters and physical restraints, use of eye glasses and magnifying lenses, hearing aids and earwax disimpaction, early correction of dehydration, use of a scheduled pain management protocol, minimization of unnecessary noise/stimuli. Strategies for the prevention and management of delirium in the ICU are important areas for future investigation. Pharmacologic The first step in pharmacologic treatment of delirium is to assess the patient’s current medications for any offending agents that may be causing or exacerbating the delirium. Inappropriate use of sedatives or analgesics may exacerbate delirium symptoms. Delirious patients may become more obtunded and confused when treated with sedatives, causing a paradoxical increase in agitation as the sedative effects wear off. In fact, benzodiazepines and narcotics that are often used in the ICU to treat “confusion” (delirium) actually worsen cognition and exacerbate the problem. A thorough review of a patient’s medications will help identify any sedatives, analgesics and/or anticholinergic drugs that may be removed or decreased in dose. There are currently no drugs with FDA-approval for the treatment of delirium. The American Psychiatric Association http://www.psych.org/psych_pract/treatg/pg/Practice%20Guidelines8904/Delirium.pdf and the Society of Critical Care Medicine clinical practice guidelines (Jacobi J, et al., Crit Care Med 2002; 30:119141) recommend haloperidol for the treatment of delirium, though it is acknowledged that this is based on sparse outcomes data from nonrandomized case series and anecdotal reports (i.e., level C data). Haloperidol is a dopamine receptor antagonist that works by inhibiting dopamine neurotransmission, with resultant improvement in the positive symptomatology (hallucinations, agitated and combative behavior, etc) and often results in a sedative effect. Haloperidol and similar agents (e.g., droperidol) have not been extensively studied in the ICU, though they are widely used anecdotally. In addition to haloperidol, other candidate antipsychotics/neuroleptic agents (e.g., risperidol, ziprasidone, quetiapine, and olanzapine) may prove to be helpful for both hyperactive and hypoactive delirium, especially with their broader receptor affinities. Patients receiving all of these antipsychotics should be monitored for adverse side effects such as QT prolongation, arrhythmias and extrapyramidal side effects. Prospective randomized controlled trials are needed to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of these agents relative to one another. Patient-Oriented Goal-Directed Sedation Delivery Increased scrutiny has recently been placed on appropriate titration of sedative and analgesic medications in critically ill patients, especially those being treated with mechanical ventilation. Patient comfort should be a primary goal in the intensive care unit (ICU), including adequate pain control, anxiolysis, and prevention and treatment of delirium. However, achieving the appropriate balance of sedation and analgesia is challenging. Without rational and agreed upon “target levels” of sedation, it is likely that different members of the healthcare team will have disparate treatment goals, increasing the chance for iatrogenic complications and potentially impeding recovery. The clinical practice guidelines of the Society of Critical Care Medicine emphasize the need for goal-directed delivery of psychoactive medications to avoid oversedation and to promote earlier extubation (Jacobi, J et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the sustained use of sedatives and analgesics in the critically ill adult. Crit Care Med; 30:119-141, 2002.) Most available evidence regarding sedatives and analgesics in ICU patients indicates that it may be less important which drugs are delivered than their proper titration using goaldirected delivery to optimize patient comfort while avoiding complications such as prolonged mechanical ventilation or reintubation. “Goal-directed delivery” of sedatives is best accomplished by the use of sedation scales to help the medical team agree on a target sedation level for each individual patient. Few available sedation scales have been appropriately tested for reliability and validity. Sedation scales with broad acceptance include (among others) the Ramsay scale, the Sedation Agitation Scale (SAS), the Motor Activity Assessment Scale (MAAS), the COMFORT scale for pediatric patients, and the Richmond AgitationSedation Scale (RASS). These are all discussed to some degree in the references for the sedation clinical practice guidelines and the RASS. The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS) was developed by a multidisciplinary team at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, Virginia. A unique feature of RASS is that it uses the duration of eye contact following verbal stimulation as the principal means of titrating sedation. RASS has been demonstrated to have excellent interrater reliability in a broad range of adult medical and surgical ICU patients and to have excellent validity when compared to a visual analogue scale and selected sedation scales. This agitation-sedation scale, which takes less than 20 seconds to perform with minimal training, has been shown highly reliable among multiple types of healthcare providers. The RASS has an expanded set of scores (10-point scale) at pivotal levels of sedation that are determined by patients’ response to verbal versus physical stimulation, which will help the clinician in titrating medications. An extensive body of new data on the RASS have been published (Sessler et al, Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002 and Ely et al JAMA 2003), with a variety of unique approaches to assess an agitation-sedation scale, which support the utility of such instruments for patient care. In accordance with recent recommendations, healthcare professionals should use valid and reliable instruments such as the RASS to implement sedation protocols for mechanically ventilated patients for goal-directed sedative and analgesic administration throughout patients’ hospital stay. The driving unmet need for goal-directed sedation practice has been met there is now an instrument that has been shown to detect variations in level of consciousness over time. Taken together, advances in neurologic assessment provided by the RASS and the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM-ICU) should lead to earlier identification and characterization of acute brain dysfunction as an “organ failure,” reductions in the random variation with which patients’ sedatives are currently managed, and appropriate interventions aimed at prevention or reversal of acute brain dysfunction. Cognitive Impairment Following ICU Hospitalization Recent research has demonstrated the presence of cognitive impairment in many patients following Intensive Care Unit (ICU) long-term care. Although estimates differ, it appears that at least 1 in 3 survivors of critical illness will experience long-term cognitive impairment of a severity consistent with mild to moderate dementia. Among specific populations, such as patients with Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS), the prevalence of cognitive dysfunction is even greater and may be as high as 80%. The acquired cognitive deficits reported by ICU survivors vary in nature and include difficulties in areas of attention/concentration, executive functioning (planning/organizing), memory (short-term, verbal, and visual), processing speed, and visuo-spatial construction. As an example please see the PDF of a figure which includes drawings from patients 6 months after ICU stay. Deficits in these areas can have significant “real world” consequences such as problems returning to work, balancing a checkbook, finding a parked car, or even following a simple recipe. Future research is needed to more fully determine the causes, but investigators believe that cognitive impairment in ICU survivors may be related to a host of factors such as delirium, hypoxemia, advanced age, low education, inflammatory and coagulopathic derangements incurred during disease such as severe sepsis or the toxic effects of large amounts of sedative and analgesic medications on the brain. Rates of mental health diseases such as depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are also disturbingly high in patients following critical illness. Clinically significant depression may occur in as many as 30% of ICU survivors, while between 15 and 40% of these patients experience symptoms of PTSD. The existence of such psychiatric syndromes, particularly when combined with cognitive impairment, typically results in a diminished quality of life