Marit Hovdal Moan - ISV - Department of Social and Welfare Studies

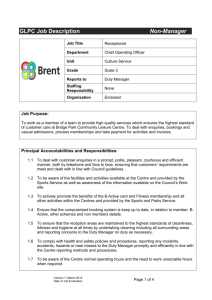

advertisement

State duties to irregular migrants: The moral relevance of political power and the principle of non-domination Marit Hovdal Moan Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) Philosophy Department Trondheim Norway Contemporary liberal democratic states generally reject that they have duties to irregular migrants beyond the constitutional minimum of protecting them from abuses of administrative power, and guarantee that they are granted equal protection before the law, in accordance with principles of procedural justice. One reason that can be – and often is – given to support this view is the state does not authorize these migrants’ presence on its territory; the implicit assumption being that, since the state has a broad sovereign right to deny non-nationals access to its territory altogether, it is morally free to determine the nature of its duties to nonnationals who reside there in defiance of this right. This paper challenges that assumption. In so doing I start with the notion that once a non-national has taken up residence under the state’s jurisdiction, the state can be said to have power over that that non-national, in the sense that it has authority to interfere in her choices of action through the implementation of laws and regulations, and thereby structure the way in which she interacts with state officials and private persons and institutions in the social space. I shall suggest that, in the particular context of contemporary liberal democratic societies, this power-relationship generates duties on the part of the state to that non-national, beyond the minimum of ensuring that state officials respect her procedural rights and fundamental liberties. In particular, I will suggest that the power-relationship between the state and the nonnational triggers a negative duty on the state to act so as not to subject the non-national to practices of domination. By ‘domination’ I mean the arbitrary, or unpredictable, constraining of an individual’s choices of action over time, through the use of force, threats of punishment, or misleading accounts of the harmful consequences of making a certain choice. The negative duty has both a direct and an indirect aspect to it: first, the state has a negative duty to refrain from directly subjecting individuals over whom it has power to practices of domination through its own actions as executed by state officials; second, it has a negative duty to refrain 1 from indirectly subjecting non-nationals to practices of domination by private actors through the design of its institutional set-up. The nature of the state’s duties to irregular migrants can be thought of, then, as a function of the institutional arrangements necessary to inhibit public officials and private agents to interfere arbitrarily in the range of possible courses of action that they are at liberty to pursue. I take the state’s negative duty not to subject irregular migrants to practices of domination to follow from an understanding of a just society as one that testifies to the principle of non-domination. Drawing on Philip Pettit’s conception of “liberty as nondomination”,1 I formulate this principle as follows: the design of society’s institutional scheme must not be such that it contributes to place any person subject to it in a position of domination vis-à-vis state officials or private persons or institutions. I understand this principle to be one that members of contemporary liberal democratic societies could reasonably accept as a necessary, albeit not sufficient, criteria for a just society. The principle should function as a moral yardstick for the justifiability of the effect that the state’s institutional scheme has on the liberty of every individual subject to it - regardless of their legal status -, lest its application becomes arbitrary and so contrary to its normative purpose. 1 Philip Pettit, Republicanism: A Theory of Freedom and Government (Oxford: Oxford University Press 1997). 2