Act I. Shaw, Bernard. 1916. Pygmalion

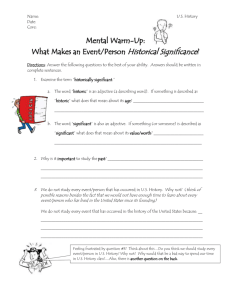

advertisement