Lesson 8-2 Sacred Nature, Humble Humanity

advertisement

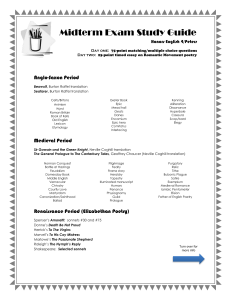

CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Eight – The Romantic Period (1700-1832) Lesson 8.2 – Sacred Nature, Humble Humanity: William Wordsworth William Wordsworth Henry Edridge (c. 1806), The Wordsworth Trust Overview: William Wordsworth saw Nature as divine: as the repository of all the best influences that would shape human beings, beginning in childhood, into people of fortitude, integrity, happiness, generosity, compassion, virtue, love, and morality. His conception of the “Child of Nature” (children raised with Nature as their teacher) exemplifies, in many ways, what we think of as a biblical “Child of God.” Nature steadies and upholds adults, too: beggars left alone to roam the countryside (rather than forced into urban workhouses), rural shepherds leading industrious, simple lives, and all of wearied humanity, broken by the hardships of the urban “din” and the burdens of existence are ministered to, in a pastoral sense, by Nature’s sacred power, which, in a pantheistic way, flows (with rejuvenating energy) through all of creation. Throughout Wordsworth’s poems, the Christian affirmation of humanity’s love of God is reconceived as love of Nature: the lover is a devout worshipper of the natural world, uttering prayers and hymns of praise, desiring the deepest intimacy with the beloved (as John Donne expressed in his Holy Sonnets in the 1600s). Lesson 8.2 – Sacred Nature, Humble Humanity: William Wordsworth ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 1 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Eight – The Romantic Period (1700-1832) Objectives: To examine the specific ways in which Wordsworth, the most devoted Nature “worshipper” among his poetic contemporaries, attributes sacred qualities to nature To consider the reasons why poets in the Romantic period chose to “worship” Nature in devout religious terms, rather than commit themselves to the Church, as an institution, and to Christian dogma To look at how Wordsworth was, in fact, quite Christian, in that he followed in a long tradition of religious figures who choose to live in wild or remote natural settings to draw closer to God: St. John the Baptist, the early Celtic saints, the Desert Fathers, and St. Francis of Assisi Readings: Two of these poems are available on The Wordsworth Trust website. The other three are in our course pack. http://www.wordsworth.org.uk/history/index.asp?pageid=39 “We Are Seven” “Simon Lee” (course pack) “The Last of the Flock” (course pack) “The Old Cumberland Beggar” (course pack) “Lines Written a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey” Lesson 8.2 – Sacred Nature, Humble Humanity: William Wordsworth ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 2 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Eight – The Romantic Period (1700-1832) 8.2.1. Biography Wordsworth lived most of his life in northern England, in the county of Cumberland, in what we now refer to as The Lake District. As you can see from the photographs below, it is delightfully beautiful, even today. In Wordsworth’s time, it was considered rather remote; it was sparsely populated primarily by sheep farmers and other agriculturalists who lived, very simply, on small plots of land. Wordsworth was born here in 1775, but he later left the region to study at Cambridge University, after which he travelled to Europe and then lived in several locations in southern England in the counties of Dorset and Somerset. In 1799, made the momentous decision to return to Cumberland, where he resided for the rest of his life. This was a radical decision for a poet; the more conventional choice would have been to live in London, where he could circulate among literary and intellectual groups of people. However, Wordsworth disliked cities, and he desired to return to the region that, he felt, had awakened his first poetic inspiration as a child and that would continue to shape his whole life as a writer. Once here, Wordsworth married, had six children, and included his beloved (unmarried) sister Dorothy in his family circle. He also invited his dear friend Coleridge to live nearby. Wordsworth developed a special interest in the local inhabitants, believing strongly that rootedness on the land, ancestral continuity, simple living, and proximity to the beauties of Nature instilled these shepherds with remarkable virtue, fortitude, humility, and generosity. Lesson 8.2 – Sacred Nature, Humble Humanity: William Wordsworth ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 3 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Eight – The Romantic Period (1700-1832) 8.2.2. Wordsworth’s Poetry William Wordsworth Robert Hancock (1798) National Portrait Gallery, London Samuel Taylor Coleridge Robert Hancock (1796) National Portrait Gallery, London The publisher of Lyrical Ballads in 1798 commissioned these portraits of the two poets. William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge published Lyrical Ballads in 1798, a collection of poems that offered a “revolutionary” new direction in English literature; it was, as they saw it, a literary parallel to the French Revolution in 1789, for it offered new subject matter and new poetic form. The two poets conceived of their contributions quite differently. As Coleridge later recorded in his Biographia Literaria, Wordsworth would contribute poems depicting “ordinary life,” while he (Coleridge) would depict “supernatural” incidents. In Wordsworth’s own “Preface” to the second edition of Lyrical Ballads (1800), he similarly explained his intention to write a new kind of poetry that depicted “low and rustic life” and that employed “language really used by men.” In literature and visual art throughout the Romantic period, we see an unprecedented interest in common— especially rural—people whose simple daily lives and strength of character are venerated and dignified in art. While this new impulse is in line with the ideals of the French Revolution—to institute a people’s republic that would overthrow an oppressive monarchy—we can also think of the figures in Wordsworth’s and Coleridge’s poems in biblical terms, for they resemble the kinds of outcast people whom Christ befriended in his ministry. Lesson 8.2 – Sacred Nature, Humble Humanity: William Wordsworth ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 4 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Eight – The Romantic Period (1700-1832) Another aspect of Wordsworth’s writing in the 1790s, connected to his concern for common humanity, is his reverence for nature as a source of spiritual renewal. The beauty of his native Cumberland, in northern England, nurtured this deep respect for nature from an early age. For Wordsworth, solitude in Nature enabled spiritual contemplativeness and a heightened sense of a transcendent God. Although raised as an Anglican, Wordsworth was not a devout church-goer through his life. Still, his broad understanding of the Christian tradition, coupled with his conviction that God’s spirit resided, most importantly, in Nature, gave him a spiritual outlook on his surroundings. 8.2.3. The Poetic Form of Lyrical Ballads These poems, as the title of the collection suggests, integrate two forms: lyric and ballad. Aiming to transpose the revolutionary ideals propelling political change in France to poetry, Wordsworth and Coleridge chose, in a comparably radical way, to yoke the plebeian, simple-storied ballad to the intimacy of personal, lyric utterance. In other words, they sought to deepen the significance of narrative by infusing it with emotional intensity. They aimed to write about common humanity, in a language that would speak to unsophisticated readers. Their poems, like biblical parables, resonate with earthy examples of simple incidents arising from humble rural life, yet they point beyond that immediacy of setting and circumstance to suggest a reality that transcends it, with moral (and often biblical) implications. Wordsworth and Coleridge employ formal experimentation to stir the reader’s response—that is, to deepen their emotional commitment to society’s outcasts: a fallen woman, an abandoned discharged soldier, an old beggar, a poor sheep farmer forced to give up his flock, a lonely Mariner traversing the world in a state of sin. These unassuming occasions and stories appeal to readers because of the form in which they are cast, combining simple stories with authenticity of feeling. Readings Two of these poems are available on The Wordsworth Trust website. The other three are in our course pack. “We Are Seven” http://www.wordsworth.org.uk/history/index.asp?pageid=39 “Simon Lee” (course pack) “The Last of the Flock” (course pack) “The Old Cumberland Beggar” (course pack) “Lines Written a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey” http://www.wordsworth.org.uk/history/index.asp?pageid=39 Lesson 8.2 – Sacred Nature, Humble Humanity: William Wordsworth ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 5 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Eight – The Romantic Period (1700-1832) 8.2.4. Literary Analysis a) Humble Rustic Life Read the first four poems listed above. Wordsworth’s outcast figures resemble the types of people we see in the Gospels, as Jesus carries out his ministry, responding to the blind, sick, rejected, and dying. In “We Are Seven,” “Simon Lee,” The Last of the Flock,” and “The Old Cumberland Beggar,” we witness precisely the same kind of encounters on rural roads, where the poetic speakers exude a Christ-like compassion for the world’s downtrodden people. Each poem offers a simple (instructive) narrative, like the Gospel stories, coupled with an affective (emotional) invocation to love one’s neighbours. Christian Love When asked “Which commandment is the first of all?,” Jesus replies, “you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind, and with all your strength.” The second greatest commandment, he says, is that you “love your neighbor as yourself. There is no other commandment greater than these” (Mark 12: 30-31). St. Paul, too, says, “Owe no one anything, except to love one another.” (Romans 13: 8). “We are Seven” The principal “event” in this poem, which gives it a simple ballad-like narrative, is the encounter between the adult and the child and their back-and-forth conversation. o Why does the adult stop to speak to her? What puzzles him? o Where does this happen? Why is the setting significant? Is the girl’s character (and appearance) shaped by her experience in Nature? If so, how? Think about the adult’s insistence on his correctness, and the child’s determination to think differently. o Whom does the poem favour? Why? How do we know? o What enables the child to claim that she and her siblings “are seven,” even though two have died, which makes them only five? What gives her that certainty and the joy that they are still an unbroken set? How do her daily activities demonstrate his firm belief? Lesson 8.2 – Sacred Nature, Humble Humanity: William Wordsworth ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 6 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Eight – The Romantic Period (1700-1832) Most would agree that Wordsworth gives the deepest insight to the child, suggesting the limitations of the adult mind. o Why is he doing that? What do children have that adults lack? o Is this a Christian idea? Think of the many references in Scripture to children as favoured by Christ: they are the ones most able to enter the Kingdom of God. “Simon Lee” This poem, too, has a simple plot. o What is it? What was Simon Lee’s former profession? Why did it end? What does he do now? (More to the point, what can he not do now and why?) o Why does the poem’s speaker stop to befriend him? Think carefully about the speaker’s advice to the reader: a poem need address only simple occasions in life; grand and dramatic events are not needed. o What small, simple gesture does the speaker do? Does it exemplify Christian love? o What is Simon Lee’s response? Why is it so profuse? Why is the speaker troubled by it? The poem is, we might say, somewhat like a parable. o What lesson is it presenting? Does it encourage acts of kindness (and critique their startling absence in life)? “The Last of the Flock” Again, the poem has a simple narrative and an interaction between the main character and the speaker, who encounters him on the road. As well, the poem is infused with lyric emotion. o What has happened to the shepherd? Why? What social problem is Wordsworth addressing? o Why does Wordsworth gives emphasis to numbers, which are carefully counted? o How is the speaker’s compassion for the shepherd conveyed? Is the speaker, himself, a kind of shepherd, noticing the stray “sheep” (a destitute man) on the road? The subject of the poem is the main character, a shepherd. o Is he just a literal agricultural man, or is he a Christ-like person? If so, how? Is he enduring his suffering with humility and patience? o How will he survive without his sheep? Can he, in a Christian way, be content with little? “The Old Cumberland Beggar” This poem, too, presents a humble human being (like the child, Simon Lee, and the shepherd). Lesson 8.2 – Sacred Nature, Humble Humanity: William Wordsworth ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 7 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Eight – The Romantic Period (1700-1832) o What does he look like? How are his movements described? Why is his age, in particular, emphasized? o How does this man survive? How does the community respond to him? Is he ever left unattended or abandoned? Why not? The speaker befriends him, after seeing him sitting by the roadside in weariness. o Why does he do that? o What claim does the speaker make for the value of the beggar? How does he contribute positively to human social life? Nature, in a sense, is the beggar’s “home.” o How are his surroundings described? o Why is Nature, as a home, important? Why is it better than a workhouse? How is he like the birds? Wordsworth wrote this work, in part, to influence politicians, as part of the poem makes clear. In the early nineteenth century, much political debate was arising about how to deal with the poor, especially as their numbers increased. o What is Wordsworth’s argument? Is it justified? Is he arguing, like Christ, that “the last shall be first”? Is he trying to radically reorder justice, along the lines of the Kingdom of God, as set out in the Beatitudes? b) Sacred Nature “Lines Written a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey” Setting: The poem is situated not in northern England, Wordsworth’s home, but in Wales, on the River Wye, near the ruins of a former Cistercian Abbey. It was abandoned in the early 1500s, when King Henry VIII sought to destroy England monasteries as a sign of his break from the Catholic Church. By the late eighteenth century, Tintern Abbey had become a popular tourist destination, appreciated for its skeletal architectural beauty and its attractive natural surroundings. Wordsworth was one of many painters and writers who came to visit Tintern Abbey. Autobiographical Occasion: Wordsworth is revisiting this spot five years after his first encounter with it. In fact, he is attracted to the natural setting “a few miles above” the abbey (that is, upriver from it), and not the structure at all. While away, he longed to return, like a lover far from his beloved. This time, he brings his sister Dorothy, although she is not Lesson 8.2 – Sacred Nature, Humble Humanity: William Wordsworth ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 8 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Eight – The Romantic Period (1700-1832) mentioned until the final stanza. The poem is about Wordsworth’s relationship to Nature, as a “lover,” and the power of his own mind. The quietness and solitude, here, enable him to know himself more deeply and to intuit the deep spiritual resources that Nature has to offer for those who love her. Tintern Abbey, Wales J.M.W Turner, North Transept of Tintern Abbey (c. 1794), British Museum William Havell, Tintern Abbey (1804), Ashmolean Museum, Oxford Lesson 8.2 – Sacred Nature, Humble Humanity: William Wordsworth ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 9 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Eight – The Romantic Period (1700-1832) Structure of the poem: o In stanza one, that loving relationship is enthusiastically restored; momentously, nothing has changed in the setting. Human life alters and falters with time, under countless burdens, but Nature has permanence, which steadies the individual. He returns here to rejuvenate his mind, body, and spirit, and he begins by describing to himself what he sees and hears. o Stanza Two is a recollection of the time away: the years of weariness and the busyness of cities; while away, however, he held this spot, and all of its lovely forms, in his memory. This is the heart of the poem: the resilience and significance of memory, to repair the individual in difficult times. o Stanza Three returns to the present moment. He notices how he, not nature, has changed. He has experienced the sadness of the human condition and no longer romps through life (and Nature) like an unthinking child. His relationship to Nature is a different one now: a more sober, thoughtful one. o Stanza Four looks to the future, as he prepares to leave again. He fears, like a lover, the loss of his beloved when he is far away. The bond might weaken when the physical presence is taken away. He leaves with some fear, but turns to his sister, now, and prays that she will be strengthened, as he has been, by this visit and that the memory that she takes with her, as they leave, will keep Nature’s healing powers intact within her. As you read the four parts, ask yourself the following questions. a. Stanza I: Present (return visit): What does he describe? Has the place changed? Is the speaker reassured? b. Stanza 2: Past (while away): What happened? What did he remember about this spot, even while far away in a very different setting? What is the value of memory, as a sustaining force? c. Stanza 3: Present (return visit): While Nature hasn’t changed, the speaker has. How has he changed since the first visit? What is his relation to Nature now? What transcendent realm does he intuit? Does that bring him joy? Lesson 8.2 – Sacred Nature, Humble Humanity: William Wordsworth ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 10 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Eight – The Romantic Period (1700-1832) d. Stanza 4: Future (his departure): What does he fear? Will his bond to Nature be broken? Is Nature like God, for Wordsworth? If so, how? What is his prayer and blessing for his sister? Is this a religious poem? Do the poems that we have read help us to interpret what he is thinking? Post your response for the class to read. 8.2.5. Question for Blackboard Discussion Look at the portrait below. It shows Wordsworth as an older man, eight years before his death at age 75, in 1850. He is standing on the top of Helvellyn, one of the highest mountains in Cumberland. Notice the rock and clouds behind him, which suggest that he is close to and part of nature. Look, too, at his contemplative gesture, with his head bowed and his expression of concentration. Clearly, in this high spot in the mountains, he is looking inward, not upward or outward to his surroundings; he is turning inside, to his mind and his soul. What might he be thinking? Is he imagining that his mind is like Nature: free and powerful and spacious and subject to turbulent fluctuation? Do the poems that we have read help us to interpret what he is thinking? Post your response for the class to read. Lesson 8.2 – Sacred Nature, Humble Humanity: William Wordsworth ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 William Wordsworth, Benjamin Robert Hayden (1842) National Portrait Gallery, London 11