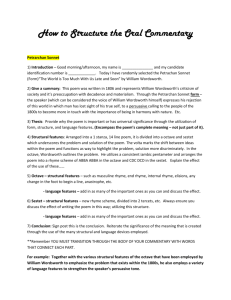

PowerPoint Presentation (Reduced)

advertisement

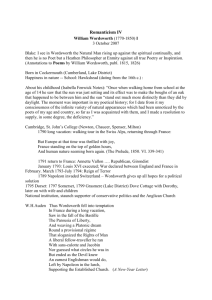

Reading William Wordsworth’s “Resolution and Independence” Poems, in Two Volumes (1807) John Constable, Dedham Vale: Evening (1802) Date of Recounted Experience: 26 September, 1800 Dates of Composition: 3 May – 4 July, 1802 Date of Publication: 1807 Latin: But later on my Muse shall speak to thee in a weightier tone, when the times afford me undisturbed rewards. Virgil, “The Gnat” Brief Background The events in the poem refer to a walk the Wordsworths took through the Lake District probably on 26 September, 1800. In a note to Isabella Fenwick Wordsworth recalls: “This old man I met a few hundred yards from my cottage at Town End, Grasmere, and the account of him is taken from his own mouth.” The poem was known in the Wordsworth household as “The LeechGatherer,” though it never received that name in print. The Many Ways to Read a Poem Before you learn how to write about this or any poem, consider that there are a variety of different methods for reading poetry. You are free to use one method or another, or to combine two or more methods (essay space pending). As a general rule, you can examine a poem without context or with context. Usually it is best to defer research into context until you have a strong sense of the poem on its own. Approach I Close Reading without Context Such seemed this man, not all alive nor dead, Nor all asleep, in his extreme old age. His body was bent double, feet and head Coming together in their pilgrimage, As if some dire constraint of pain, or rage Of sickness felt by him in times long past, A more than human weight upon his frame had cast. Himself he propped, his body, limbs, and face, Upon a long grey staff of shaven wood; And still as I drew near with gentle pace, Beside the little pond or moorish flood, Motionless as a cloud the old man stood That heareth not the loud winds when they call, And moveth altogether, if it move at all. 75 80 Approach II Close Reading with Context Dorothy Wordsworth, Grasmere Journals. Friday, 3 October, 1800. [W]e met an old man almost double. He had on a coat thrown over his shoulders above his waistcoat and coat. Under this he carried a bundle and had an apron on and a nightcap. His face was interesting. He had dark eyes and a long nose….He was of Scotch parents but had been born in the army. He had had a wife, ‘and a good woman, and it pleased God to bless us with ten children’; all these were dead but one of whom he had not heard [from] for many years, a sailor. His trade was to gather leeches, but now leeches are scarce and he had not strength for it. He lived by begging and was making his way to Carlisle where he would buy a few godly books to sell. He said leeches were very scarce partly owing to this dry season, but many years they have been scarce. He supposed it owing to their being much soughtafter, that they did not breed fast, and were of slow growth….He had been hurt in driving a cart: his leg broke, his body driven over, his skull fractured. Ways of Seeing his voice to me was like a stream (l. 114) the man did seem/ Like one whom I had met with in a dream (ll. 116-17) In my mind’s eye I seemed to see him pace/ About the weary moors continually,/ Wandering about alone and silently (ll. 136-17) Wordsworth, Preface to Poems (1815) Motionless as a cloud the old man stood That heareth not the loud winds when they call, And moveth altogether, if it move at all. The imagination is not a mere storehouse mental copies of real-life objects. It “denot[es] operations of the mind upon…objects, and processes of creation or of composition governed by certain fixed laws.” In this poem the cloud “is endowed with something of the power of life to approximate it to” the old man, and the old man is “stripped of some of [his] vital qualities to assimilate [him] to” the cloud, so that “the two objects unite and coalesce in just comparison.” “Observations on the Diseases in November,” Universal Magazine of Knowledge and Pleasure 107 (Dec. 1800), 107. George Havell, “Leech Finders,” in Costumes of Yorkshire (1814)