Carla Della Gatta 9th World Shakespeare Congress Global Spin

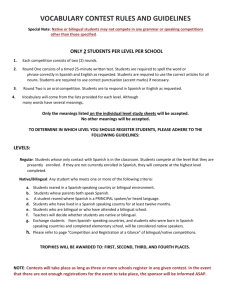

advertisement

Carla Della Gatta 9th World Shakespeare Congress Global Spin-Offs Panel July 22-26, 2011 Prague Shakespeare and American Bilingualism: Borderland Productions of Romeo y Julieta “To be Latino in the United States is rather to participate in a unique process of cultural syncretism that may become a transformative template for the whole society.” Mike Davis, Magical Urbanism, 2001 I am not such a truant since my coming, As not to know the language I have lived in: A strange tongue makes my cause more strange, suspicious; Pray, speak in English. Queen Katharine, Henry VIII, (III.i.42-46) Over the past few years, three American Shakespeare companies produced bilingual Spanish-English adaptations of Romeo and Juliet, Shakespeare’s most widely known play. Each production fused Elizabethan English with modern-day Spanish, a complex juxtaposition not only because of the use of two languages, but also due to the older English of Shakespeare. The productions at Austin Shakespeare in 2009, the Old Globe in San Diego 2008-10, and the 2008 staged-reading by Chicago Shakespeare all point to a growing interest in bilingual performances of the Bard in the United States. With the growing Latino population and efforts in cultural outreach by established Shakespeare theaters, further bilingual productions may be on the horizon. This paper explores the positioning of bilingual Romeo y Julietas in a multicultural country as a precursor for further bilingual productions of all periods and genres. Ultimately, the 1 perception of Latinidad in the United States is examined through this exploration of bilingual Shakespeares and the new space and language that the productions create. THE SURGE OF LATINIDAD While productions of Romeo y Julieta mark a hybrid genre of translation and adaptation, three other Shakespearean-influenced bilingual Spanish appropriations also emerged across the country in the past few years. First, the Educational Theatre Company in Arlington, Virginia, produced two bilingual shows in 1998, Bottom's Dream and The Comedy of Errors. According to Tom Mallan, Professional and Curriculum Development and Director for both of ETC’s bilingual productions, “both shows had concepts that re-cast the Shakespeare characters as either Americans or Latin Americans, then they interacted accordingly”. In both shows, some characters spoke English and others Spanish in order to indicate a greater chasm between characters and locations1. In 2005, Georgia Shakespeare produced their first bilingual show by creating a play for elementary school children called Miguel's Shakespeare Adventure. According to Allen O’Reilly, Education Director, “the lines were delivered alternately between English and Spanish”. It was brought back for 2006 and toured at the Outrageous Fortune Theatre Company in El Paso, Texas2. Most recently, in 2010, Caitlin McWethy, a student at Drew University in New Jersey, produced a bilingual version of As You 1 “In Bottoms Dream we cut the lovers out of MSND completely, and cast the Mechanicals as gringo tourists visiting Latin America on some kind of 'community theater tour’. . . One neat thing was that in the Titania/Bottom scenes where she is usually speaking verse and he is speaking prose, the effect was heightened by her speaking Spanish and him [Elizabethan] English” (Mallan). Further, “in ComedyA of Error(E)s we re-cast Syracuse as the US and Ephesus as Cuba. . . We had a great bilingual actor play both Antipholi, one brother speaking American English as a native (and dressed as a traveling American) and one speaking Cuban Spanish (and dressed very differently); we had a single actor do the same with Dromio” (Mallan). O’Reilly said, “even though we live in a heavy Hispanic area, the show had moderate success both years. One of the criticisms was that the Spanish was "European" as opposed to Mexican. The tour in El Paso was tweaked to accommodate that communities' students and was more successful there”. 2 2 Like It. “McWethy chose to set the play in a place which is perceived to be as unlike the Garden of Eden as possible, a barrio in Mexico City” (Kraynak). All three of these productions show an immense amount of creativity on the part of the directors and adaptors, using Spanish and Latino culture to enrich and alter Shakespearean plays for student audiences. Other Latino and Spanish festivals hosted by Shakespearean companies have emerged recently. In 2008, the Oregon Shakespeare Festival created a “Festival Latino” 3 in which they offered bilingual backstage tours, Spanish captioning for six of their plays” and other cultural activities and performances4. In 2009, GALA Hispanic Theatre and Shakespeare Theatre Company, both in Washington, D.C., co-hosted a “Loving Lope” festival in honor of Lope de Vega in which two of his plays were performed. Along with cohesive marketing, additional events were offered, and The Spanish Embassy and the Washington Performing Arts Society cohosted an event during the festival5. Ultimately, Latino and Spanish cultures are being celebrated, and capitalized, by these festivals and productions. Motivation for these productions varied from inspiration to outreach to sheer accident. At Drew University, McWethy got her inspiration from her interpretation of Harold Bloom’s The Invention of the Human. She was unfamiliar with Spanish, so another student wrote the 3 The success of this one-time event helped to shape a broader cultural outreach program. According to the Audience Development Manager, Freda Casillas, “Festival Latino was a success and has morphed into CultureFest, an event will [be held] every other year. [The] first CultureFest was in 2010” (Casillas). 4 Until Festival Latino in 2008, OSF rarely engaged with Latino playwrights or Spanish- themed plays. Since 1990, these included the 1995 production of Lorca’s Blood Wedding, two plays by Octavio Solis performed in 1999 and 2005 respectively, Nilo Cruz’s Lorca in a Green Dress in 2003, and a play by Luis Alfaro in 2008. During the 2009 season, they premiered a musical version of Don Quixote, adapted by Solis. In 2010, they produced American Night: The Ballad of Juan Jose by Richard Montoya and Culture Clash and also hosted a staged reading of Lope de Vega’s Fuenteovejuna. 5 The productions overlapped by a little more than a week so that theatregoers could experience Lope in different forms, yet the Spanish-speaking audience members didn’t have full access to both productions because only GALA’s production offered subtitles. Hugo Medrano and Akiva Fox, the Artistic Directors of GALA and STC, respectively, both felt that the festival was a success (Medrano and Fox). 3 translation and additional poetry in Spanish. By contrast, at ETC, Mallan chose to do bilingual work because he had done similar work with students in Costa Rica and Ecuador, and it is “always lots of fun to heighten everyone's understanding (of all language) this way” (Mallan). He was also motivated by the opportunity for the work to travel to different audiences. According to Mallan, “ETC also partly took this on because there are bilingual education initiatives in the school system in Arlington and nearby, so we were able to integrate this with bilingual workshops for school children. We also performed Bottom's Dream at the Smithsonian”. By contrast, the Loving Lope Festival in Washington, D.C. occurred due to the announcements of the theatrical season by GALA and the Shakespeare Theatre Company. Both theatres announced they would run Dog in A Manger, and GALA kindly gave the title to STC. The idea for the festival resulted from cooperative planning between the two theaters and artistic directors. ROMEO Y JULIETA I will focus on the three productions of Romeo y Julieta as indicative of the different approaches to bilingual productions. These productions adhered more closely to the original Shakespearean text than the previous mentioned adaptations. Also, the Old Globe, Austin Shakespeare, and Chicago Shakespeare are three leading theaters for Shakespearean performance in the United States. They are each located in three densely Latino6 areas, with each area involving a different ethnic Latino community. I used the term “Latino” here as a blanket term to encompass people from all Spanish-speaking countries, including Mexico, Latin America, and South America. In the United States, the preference at this time is to use “Latino” as the broadest term, which I employ for the remainder of the essay. Note that the term “Hispanic” also includes those who emigrated from or who have ancestors in Spain. “Hispanic” is mostly used by those outside the Latino and Hispanic communities. 6 4 Each theater used different amounts of Spanish to engage their audience. Austin Shakespeare had a "successful, semi-bilingual production of Romeo & Juliet" according to the company's website. Alex Alford, Managing Director of Austin Shakespeare Festival, said “’semi-bilingual’ was a term used to let the audience know that it wasn't a 50/50 English/Spanish formula”. The Old Globe in San Diego produced three Romeo y Julietas with their summer student camp, one each in 2008, 2009, and 2010, respectively. Director of Education, Roberta Wells-Famula said that in 2008, the Old Globe’s “script incorporated much of the Neruda7 script as well as some translation by a former Globe Education Department writer/educator” (WellsFamula). For Chicago Shakespeare’s staged reading, Director Henry Godinez8 abridged the play and playwright Karen Zacarías9 did the translation, using the Neruda script as a reference. Spanish and English were used almost equally and within the same lines. Along with the quantity of Spanish used, each theater incorporated Spanish appropriately for their audience. For Austin Shakespeare, “the production was set in South Texas in the 1940's with a Pachuco flavor” (Alford). This setting resonates with the audience in Austin, where a specific form of Spanish-English mixing that is commonly referred to as “Tex-Mex”. Tex-Mex refers to a style of music, food, and language that incorporates both Mexican Spanish and American English influences. “We estimate that the actual Spanish used was about 7%” (Alford). To some, this would resonate as a “Spanglish10” version of Shakespeare, and therefore 7 Pablo Neruda published a translation of Romeo and Juliet in 1964. It is the most widely known Spanish translation of the play by a Latino writer. Godinez is a veteran of CST’s acting company, co-founder of Teatro Vista (Chicago’s leading Latino theater), director of Chicago's Latino Theatre Festival, a director at the Goodman Theater, and Artistic Director at Northwestern University’s Theatre Department. 8 9 Zacarías is also the founding artistic director of Young Playwrights' Theatre in Washington, D.C. “Spanglish” is a mixture of English and Spanish, but the term has a derogatory connotation to it. The OED defines it as “a type of Spanish contaminated by English words and forms of expression, spoken in Latin America”. 10 5 turn off a tier of patrons, but Alford felt that even the slightest use of Spanish would engage a larger audience. For the Old Globe, Spanish was used to show the division between the families, with the Capulets as Spanish speakers and the Montagues as English speakers. Much like the famous musical adaptation, West Side Story, the households were of different classes and backgrounds. Wells-Famula said “most of the Spanish language was incorporated in scenes with the Capulets and went back and forth between Spanish and English so that the audience would understand what was going on” (Wells-Famula). This twist was also seen in the recent 2009 Broadway production of West Side Story, directed by Arthur Laurents, who wrote the original book. It had the Sharks singing and speaking in Spanish11 to “at last elevate the Puerto Rican Sharks to their rightful place as equals to their deadly white rivals” (Pilkington). Both the Old Globe’s productions and the new version of West Side Story heighten the Shakespearean premise of division by incorporating language and class divisions into the families’ acrimonious relationship. After the 2008 production, the use of Spanish changed for the Old Globe, and bilingualism became an even greater part of the show. According to Wells-Famula, in 2009 they used less Spanish but “also included a deaf student actress so we also incorporated American Sign Language in her scenes. The production was interpreted for the audience in both American Calling the production “Tex-Mex” or “bilingual” may ultimately indicate the same mixture of language, but both terms do not carry the negative implications of “Spanglish”. To note, some of the songs were changed back to English after six months of the show’s run. According to The New York Times, mid-way through the run “‘A Boy Like That’ [was] predominately sung in English to the original lyrics and selected dialog and lyrics in ‘I Feel Pretty’ [was] reverted to English” (Itzkoff). Laurents was cautious in his explanation for the change stating, "From the outset, the Spanish in West Side Story was an experiment. It's been an ongoing process of finding what worked and what didn't, and it still continues” (Itzkoff). Some viewed this change as catering to monolingual English-speaking audiences who were thrown off by the use of Spanish. 11 6 Sign Language and Mexican Sign Language12”. The multiple languages of the Old Globe production signal the only polylingual production of Shakespeare in the United States. Because ASL and LSM are both visual-spatial languages rather than aural languages, staging must be altered to adhere to the rules of both sign languages. Further, there are significant differences between ASL and LSM as LSM uses more initialization than ASL and both have no grammatical similarities to their spoken languages. For the staged reading hosted by Chicago Shakespeare Theater, Spanish was used to repeat some lines and to replace others. The setting was a modern Latino community, and renowned actress Elizabeth Peña starred as Lady Capulet. Chicago Shakespeare’s script was more evenly bilingual throughout than the other two productions discussed previously. Some speeches were entirely in one language, such as the Prince’s first speech and all of Queen Mab, both in English. An example of the interchange is seen from the prologue below. SEVERAL VOICES 1 Two households, 2 Dos casas 3 both alike in dignity/ ambas en nobleza iguales 4 En la bella/ In fair 5 Verona 6 where we lay our scene, 7 Y un odio antiguo que engendra un nuevo odio 8 From ancient grudge break to new mutiny 9 Where civil 10 sangre tiñe sus civiles manos 11 Y aquí desde la oscura entraña de los dos enemigos 12 son nacidos dos amantes desdichados bajo estrella rival 13 A pair of star-cross-d lovers take their life; 14 Su lamentable fin, su desventura 15 Entierra con su muerte/ (bury) their parents' strife. (Godinez 2). For further inquiry into productions with ASL, see Peter Novak’s translation of Twelfth Night, the first ASL translation of a Shakespearean play. Also note Oregon Shakespeare Festival’s inclusion of deaf actor Howie Seago as the ghost of King Hamlet, Tubal, and Poins in their 2010 season. 12 7 A reading of the prologue shows two forms of bilingualism at work. The first is the example of repeating a phrase in Spanish after using the English as seen in the first two lines. This is also done in the reverse; phrases are translated into Spanish and then repeated in English. Line 5 brings the two languages to unity with “Verona” which is pronounced and spelled the same way in English and Spanish. The second form involves starting a line in one language and finishing it in another. It is first evident in lines 9-10 where the thought starts in one language “Where civil” and finishes in another “sangre tine sus civiles manos”. A third form, realized numerous other places in the script, involves intermixing languages within the same sentence. When Mercutio tells Romeo to borrow Cupid’s wings, Romeo replies, “I am too sore herido with his shaft / Under love's heavy burden me hundo” (Godinez 11). Here words are interwoven within a single phrase, generally selected by identifiable words in a particular language, but also to keep the meter regular. Both lines contain five iambs, so they retain the rhythm of Shakespeare’s script even though some words are in contemporary Spanish. This type of flexibility seen in a bilingual production is not possible within a monolingual translation. CODE SWITCHING AND BILINGUALISM These three forms, the repetition of phrases in another language, the completion of a thought in a different language than the beginning of the line, and intermixing within one phrase are examples of “sign codes” in bilingual speech patterns. John M. Lipski defines “Code switching” as “switching between two languages within the same discourse involving the same individuals” (Lipski, Varieties 229-30). This phenomenon is common in the United States among Spanish/English speakers but Lipski notes that code switching is not common in all bilingual communities, as evidenced “by the relative scarcity of intrasentential French-English 8 shifting in Canada” (Varieties 239). This switching mid-sentence may seem confusing to many, and indeed, it is off-putting to those who do not master both languages. According to Ana Celia Zentella, “Spanish and English monolinguals are thrown off, or put off, by the rule-governed and rule-breaking switches alike, especially when in written form, but bilinguals always know where to laugh to cry” (58). This is the reason that terms such as “Spanglish” carry a pejorative association and ultimately discredit the advanced linguistic and conceptual ability that code switching requires. According to Lipski, code switching occurs in two situations. The first is an “unconscious anticipation of words or phrases intimately linked to the second language” (Lipski, Varieties 234). Benvolio’s first line to Romeo in CST’s script is “Buenos dias, cousin” (Godinez 3). In this instance, the prevalence of Shakespeare’s use of “cousin” (fifteen times) or “coz” (four times) within the original script tie “cousin” to a consistent and identifiable word in Romeo and Juliet. “Cousin” has a broader meaning other than a relative, and it can also be used “ As a term of intimacy, friendship, or familiarity13” (OED). The direct translation in Spanish, “primo,” does not carry such multiplicative connotations. Therefore the use of “cousin” must be retained in English for a fuller meaning that the word conveys. By contrast, “Good-morrow,” which “Buenos dias” replaces rather simply, is only used that one time in the original script. “Goodmorrow” is an antequated way of saying “Good morning,” thus causing the morning greeting in contemporary Spanish to be more easily understood than the expression in Elizabethan English. The second way in which code switching appears is through “complex or compound sentences in which code switches occur between the individual clauses because, in effect, each 13 The OED dates this meaning back to 1418 and twice cites Shakespeare for this usage in 1616 for Henry XI Part III and All’s Well That Ends Well. 9 full sentence is produced in a single language” (Lipski, Varieties 234).14 An example of this is seen in Romeo’s response to Benvolio later in that same conversation. “Here's much to do with hate, but more with love. / Why, then ay, un amor odioso! Y, Ay,un odio amoroso!” (Godinez 4). The typological similarity within the two languages faciliates the process of switching. The ideas resonate in the second sentence, and the switching of “hate” and “love” in the English portion establishes contrast. The second portion in Spanish does not include antithetical ideas, but simply reverses the word order. The lines juxtapose ideas and structure, making use of the rhetorical tool of antimetabole. Further, “hate” and “love” are stated once in English and then twice in Spanish; this repetition across languages facilitates understanding of the concepts to bilingual speakers and allows them to be identifiable for monolingual speakers. The third form, of intersplicing, is what is most open to criticism as a degredation of both languages. Jane Hill uses the term “Mock Spanish” to describe “the insertion of Spanish words and phrases like mañana [and] Ah-dee-os” (Zentella 52). The selection of words in either language can be as deliberate as the passage cited above which maintained the meter and selected words in each language that had the fullest signification. But to the ear that cannot maneuver between languages with this level of facility, this manner of code switching can seem the least desireable. Despite the facility of code switching among bilinguals, both consciously and unconsciously, the practice does not resonate with monolingual speakers because of the perception that it is destroying a dominant culture and due to a feeling of exclusion by that monolingual group. Michael Holquist studies the ontological status of bilingualism and concludes that monolingualism “presumes a concept of the autonomous self and of the uniquely The title of Shana Poplack’s 1979 seminal essay “’Sometimes I’ll Start a Sentence in Spanish Y TERMINO EN ESPANOL’: Toward a Typology of Code-Switching’” on the study of el bloque Puero Ricans in New York illustrates this phenomenon. 14 10 homogenous state” (25). This idea of selfhood and nationhood is upset by the sharing with another language, and therefore another culture and new identity. While Alexandra Jaffe illustrates a shift in bilingualism from “cultural-deficit towards bilingualism-as-added-value” (51) over the last ten to fifteen years, she too concludes that modern notions of national identity are tied to a single language (51-52)15. Spanish is the most frequently taught language in American education. (Lipski, Varieties 10) but it retains an association with negative stereotypes of Latino communities along with issues with immigration, fear of job losses, and culture wars. All are wrapped up in the antagonism of code-switching, or more colloquially referred to as Tex Mex or pejoratively as Spanglish. THE FUTURE OF BILINGUAL PRODUCTIONS It is difficult to discern if these productions mark the beginning of a trend in bilingual productions of Shakespeare or, due to the foreignness in style and the inability to gauge the “success” of the productions, if they will disappear from American theaters. Austin Shakespeare’s production occurred during their annual free Shakespeare in the Park in the summer. For the Old Globe, all forty high-school students admitted to the Summer Shakespeare Intensive receive a full scholarship for the four-week session. Also, Chicago Shakespeare’s staged reading was performed at a local high school, for free. A free talk-back session with the director and cast followed the reading on both nights. The accessibility of free productions of Shakespeare in the United States is quite common due to arts funding, though the ability to perform non-traditional appropriations remains a struggle. 15 Sandra R. Schecter and Robert Bayley agree on the coexistence of antithetical views of American Spanish/English bilingualism. “Generally, elective bilingualism is viewed by the larger society as prestigious, whereas circumstantial bilingualism has been considered a deficit” (Schecter 194). See also Frances R. Aparicio’s notion of “differential bilingualism” in “Whose Spanish, Whose Language, Whose Power? An Ethnographic Inquiry into Differential Bilingualism.” Indiana Journal of Hispanic Literatures. Vol. 12, 1998. 5-25). 11 Reception was positive for all three productions, but that doesn’t ensure further experiments with this style. In Austin, Alford estimates that “Of about 8500 total audience members, approximately 10% were Hispanic. Entire extended families came, many with little or no English”. At the Old Globe the 2008 “performance was well-received by the audience and the students loved the bilingual aspect. We did hand out a scene-by-scene plot synopsis so that people could keep up” (Wells-Famula). Despite the perceived positive reception, none of the theaters have no plans for another bilingual production. The Old Globe had their final bilingual production in 2010 because of personnel changes and fewer Spanish-speaking students. WellsFamula said that she “really enjoyed the bilingual program and am sorry that we are no longer doing it.” Funding through CST for cultural productions was refocused and mostly relegated to the strength of Teatro Luna within the Latino community to fulfill this audience need. But the growing Latino population will shift and overtake the ageing Latino population in America, and I contend will alter the prejudice and perspective of bilingual theatrical productions. Latinos under the age of 25 are growing at a faster rate than any other youth group16. As evidenced by the excitement of the student groups at the Old Globe and the setting of Chicago Shakespeare’s production at a local school, the younger generation is more apt to embrace code switching and language play than the older generation. This may be due to assimilation concerns as well as Zentella’s contention that language play “flourishes during teen years, when slipping in and out of two languages and several dialects enhances the multiple identities that Latin@ adolescents try on” (58-9). Romeo and Juliet is a love story between “27.2 [is the] median age, in years, of the Hispanic population in 2005. This compares with 36.2 years for the population as a whole” (latinostories.com). Further, according to a report released in March 2001 by the Pew Hispanic Center, there were 17.1 million Latinos among children under the age of 17, constituting 23.1% of the population in this age group . . . Latino adults now make up 14.2% of the adult population in the country” (votolatino.org). 16 12 teenagers, and it is this Shakespearean play that is taught in nearly every American high school as means to engage young people in Shakespeare, and theatre, for typically the first time. According to Godinez, For many in the United States, growing up bilingual is a fact of life. . . It cuts across the generations. Spanish at home, English at work or school, both with friends. Finding how these two headstrong teenagers fall for each other in a world divided not just by two households, but by two languages, is fascinating. (chicago.broadwayworld.com) This experience, while seemingly appealing to a niche bilingual minority, is in actuality, a group on the rise. Not only is the young Latino population growing and shaping American culture, but the Latino population as a whole has grown significantly in the last decade17. As of the 2010 U.S. Census, Latinos comprise 16.3% of the population, larger than any other minority group (2010.census.gov), and by 2050, U.S. Latinos will total to 96-100 million, constituting “the third largest Latin American nation, behind Brazil and Mexico” (Viego 108). Yet the shift from Spanish to English amongst American Latinos is complete in two generations18. It is this shift, this space between one language and another, that creates a space for a new type of theatrical production. But the creation of a third language is ultimately what is reflected in bilingual productions, and most aptly in bilingual Shakespearean productions. Shakespeare is the most performed playwright worldwide, and the United States has more Shakespeare festivals than any other country. A trend that begins in Shakespearean appropriations in the nation’s most renowned theaters, free and accessible to the public, will most likely be replicated elsewhere. Latinos are growing at a faster rate than any other ethnic group. “More than half of the growth in the total population of the United States between 2000 and 2010 was due to the increase in the Hispanic population” (2010.census.gov). 17 See Lipski, Varieties p.5. Also, Alejandro Portes and Lingxin Hao, “E Plurbis Unum Bilingualism and Language Loss in the Second Generation.” Sociology of Education. Vol. 71, No. 4. 1998. 269-94). 18 13 The mixing of English and Spanish has taken shape over the last thirty years with the growing Latino population, but intersplicing modern-day Spanish with Elizabethan English is entirely a new phenomenon. Yet the controversy will remain. Zentella feels that “bilingual dexterity” allows speakers to “poke fun at their own semantic and grammatical constraints” (58) while Lipski claims that it will ultimately result “in the deterioration of the Spanish language” (“Spanish” 198). Different members of the Latino community relate to both of these conclusions, which is the reason that code-switching is not necessarily favored by native speakers of either language. Bill Ashcroft argues that code-switching can ultimately confirm identity19, and I agree that it will confirm not a Latino or an Anglo identity, but an intercultural American one. I contend that these productions are not simply translations of Shakespeare or typical adaptations; they are a site of creating a new space and a new language. This new space, often called la frontera or the borderlands20, is both literal and figurative in the American Latino experience. Latinos are spread throughout the United States, but for those living in the southwest United States, the territory where they reside was once Mexico. Ashcroft notes, “In an enormous region covering five states, many Chicano/as are still living in their ancestral homeland” (23). Unlike diasporic communities, many Latinos did not move away from their homeland, rather, the lines delineating their homeland moved away from them. Bilingual productions of Shakespeare are not a post-colonial attempt to appropriate or subvert “Rather than diluting cultural identity, linguistic versatility and adaptability can confirm it. This is true of all postcolonial literatures, which produce hybrid narrative strategies such as code-switching, glossing, syntactic fusion, untranslated words, all of which function both to hybridize and to distance, to communicate while establishing difference” (Ashcroft 21). 19 For a more thorough discussion of views on the borderland, see Viego. He discusses Walter Mignolo’s idea of “border gnosis”, Tomás Ybarra-Frausto’s “rascauche aesthetic” and Chela Sandoval’s “oppositional consciousness”, and José Estéban Muñoz’s “disidentificatory practices” along with Anzaldúa’s “border subject” (126). 20 14 the colonizer’s literature, rather they are the mark of a new genre and growing culture in a country that claims Shakespeare for itself. The term “Latinidad” is used to describe the growing influence of Latinos on American culture. Just as Viego contends that the idea that U.S. culture “is being Hispanicized or Latinized is to suggest . . . the present future tense” (119), Beltrán employs Deleuze and Guattari to explain it’s rhizomatic nature21, that “rather than being defined in terms of some particular end, Latinidad ‘is always in the middle, between things … intermezzo’” (167). It is this middle as well as the future, that allows for the growth of new forms of language and culture. The productions of Romeo y Julieta over the past three years are indicative of a new genre that can only be created in the space of a bilingual borderland. M.S. Suárez Lafuente claims “difference has to be reached precisely through language by deconstructing, by undoing the linguistic process, widening ‘lost intersticios,’ the fissures, as the best way to subvert the patriarchal ‘I’” (138). It is only through the subversion of a monolingual selfhood and nationhood that various forms of bilingualism will be accepted in the United States. The mixing of a sixteenth century British playwright and a twenty-first century Spanish vernacular is a means of creating this new American genre. 21 See also Ashcroft p.24. 15 WORKS CITED Alford, Alex. Personal Communication. 30 Dec 2010. Ashcroft, Bill. “Chicano Transnation.” Imagined Transnationalism: U.S. Latino/a Literature, Culture, and Identity. Ed. Kevin Concannon, Francisco A. Lomelí, and Marc Priewe. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009. 13-28. Print. Beltrán, Cristina. The Trouble With Unity: Latino Politics and the Creation of Identity. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2010. Print. Casillas, Freda. Personal Communication. 15 Feb 2009. Chicago.broadwayworld.com. “’Romeo y Julieta’: Shakespeare en Español.” 24 Jun 2008. Web. “Cousin.” Def.5. The Oxford English Dictionary. 2nd ed. 1989. Oxford UP. 15 Feb 2011. Web. Fox, Akiva. Personal Communication. 20 Dec 2010. Godinez, Henry and Karen Zacarías. Romeo y Julieta. 2008. Print. Holquist, Michael. “What is the Ontological Status of Bilingualism?” Bilingual Games: Some Literary Investigations. Ed. Doris Sommer. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003. 2134. Print. Itzkoff, Dave. “Bilingual ‘West Side Story’ Edits Out Some Spanish.” Nytimes.com. 25 Aug 2009. Web. Jaffe, Alexandra. “Minority Language Movements”. Bilingualism: A Social Approach. Ed. Monica Heller. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007. 50-70. Print. Kraynak, Marissa. “Shaking up Shakespeare: The Bard goes bilingual.” Drewacorn.com. 26 Mar 2010. Web. Lafuente, M.S. Suárez. “M/other Tongues in Borderlands in Contemporary Literature in English”. Literature and Ethnicity in the Cultural Borderlands. Eds. Jesús Benito and Ana María Manzanas. New York: Amsterdam, 2002. 135-44. Print. Latinostories.com. Accessed 15 Apr 2011. Web. Lipski, John M. “Spanish, English, or Spanglish? Truth and Consequences of U.S. Latino Bilinigualism”. Spanish and Empire. Ed. Nelsy Echávez-Solano and Kenya C. Dworkin y Méndez. Nashville: Vanderbilt UP, 2007. 197-218. Print. 16 --- Varieties of Spanish in the United States. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown UP, 2008. Print. Mallan, Tom. Personal Communication. 1 Jan 2011. Medrano, Hugo. Personal Communication. 2 Dec 2010. O’Reilly, Allen. Personal Communication. 9 Apr 2011. Pilkington, Ed. “Latino liberation: Sharks sing in the language of their streets as West Side Story goes bilingual on Broadway.” The Guardian. 20 Mar 2009. Web. Schecter, Sandra R. and Robert Bayley. Language as Cultural Practice: Mexicanos en el Norte. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2002. Print. “Spanglish.” Def.1. The Oxford English Dictionary. 2nd ed. 1989. Oxford UP. 15 Feb 2011. Web. Viego, Antonio. Dead Subjects: Toward a Politics of Loss in Latino Studies. Durham: Duke UP, 2007. Print. Votolatino.org. Accessed 15 Apr 2011. Web. Wells-Famula, Roberta. Personal Communication. 7 Feb 2011. Zentella, Ana Celia. “’José, can you see?’: Latin@ Responses to Racist Discourse.” Bilingual Games: Some Literary Investigations. Ed. Doris Sommer. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003. 51-68. Print. 2010.census.gov. Accessed 15 Apr 2011. Web. 17