(DE)CONSTRUCTIONS OF SOUTH`AFRICA`S EDUCATION WHITE

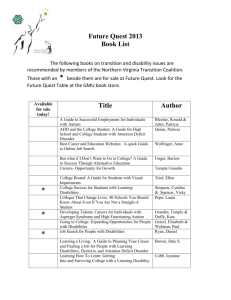

advertisement