A TAXONOMY OF THE UNCERTAINTY SOURCES PERCEIVED BY

advertisement

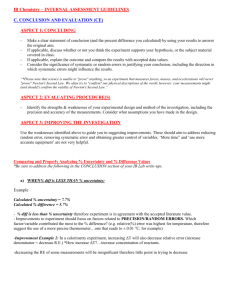

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL BEHAVIOR, 7(1), 1-21 OF ORGANIZATION THEORY AND SPRING 2004 A TAXONOMY OF THE UNCERTAINTY SOURCES PERCEIVED BY PUBLIC SECTOR MANAGERS IN HONG KONG Kathleen E. Voges, Richard L. Priem, Christopher Shook and Margaret Shaffer* ABSTRACT. Perceived environmental uncertainty (PEU) is a foundational concept in organization studies. The PEU typologies used in organizational research were developed using private sector managers. But, do public sector managers perceive the same uncertainty sources? We asked public sector managers in Hong Kong to identify and group uncertainty sources facing their organizations. Multidimensional scaling and cluster analysis yielded classes of uncertainty sources that differ from those developed using private sector managers. INTRODUCTION Many scholars view the organization’s environment as a source of information perceived by its members (Daft, Somunen & Parks, 1988; Gioia & Thomas, 1996; Thomas, Clark & Gioia, 1993). Research has -----------------------* Kathleen E. Voges is a doctoral candidate, Department of Management, University of Texas at Arlington. Her research interest is in privatization, particularly the study of differences between public and private sector managers. Richard L. Priem, Ph.D., is the Robert L. and Sally S. Manegold Professor of Management and Strategic Planning, School of Business Administration, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. His research interests include the strategy making process and chief executive decision-making. Christopher Shook, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor, Department of Management, Auburn University. His research interests include the strategy making process and methodological issues in strategy research. Margaret Shaffer, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor, Department of Management, Hong Kong Baptist University. Her research interests are in the areas of crosscultural studies, expatriation and work role adjustment. VOGES, PRIEM, SHOOK & SHAFFER Copyright © 2004 by PrAcademics Press 2 VOGES, PRIEM, SHOOK & SHAFFER found that managers’ perceptions of environmental uncertainty (PEU) are related to managerial actions such as: scanning, interpretation, strategy making processes, and political tactics (Galaskiewicz & Bielffeld, 1998; Lant, Milliken & Batra, 1992; Priem, Love & Shaffer, 2002; Yasai-Ardekani & Nystrom, 1996). Many theories of organization - such as open systems theory and strategic contingency theory - allot the environment a crucial role in the study of organizations (Hofer, 1975; Katz & Kahn, 1978). Separately, scholars also note important differences between private sector and public sector organizations (Nutt, 1999; Perry & Rainey, 1988). For example, the primary goal of the private sector is profitability, whereas the primary goal of the public sector is to serve citizens (Willcocks & Currie, 1997). Government regulatory oversight differs and organizational structures differ between the private and public sectors (Rainey & Bozeman, 2000). Moreover, organizations with different structures likely perceive the environment differently, as do organizations with differing goals and regulatory controls (Aldrich & Pfeffer, 1976). Despite these differences between the private and public sectors, classifications of environmental uncertainty sources derived from the private sector are being used in public sector research (Bryson, 1995). Public sector management studies that employ the PEU construct typically present public managers with categories from a private sectorbase, and then ask them to rate the level of uncertainty facing their organization in each category. If the chosen typology does not reflect the classifications used by public managers, however, research results could lead to basic misunderstandings of both the organizational environment and public managers’ behavior. Even more troublesome, this use of private sector PEU typologies could induce private sector researchers toward heedless generalization of public sector results to private sector research, thereby blurring potentially crucial distinctions between private and public managers. Given the importance of the PEU construct in studying managerial actions and subsequent organizational performance, a direct examination of the uncertainty sources facing public sector managers is warranted. Our study takes an initial step toward addressing two fundamental research questions: TAXONOMY OF THE UNCERTAINTY SOURCES PERCEIVED BY PUBLIC SECTOR MANAGERS 3 1) What are the sources of uncertainty perceived by public sector managers? and 2) Do public sector managers perceive the same uncertainties as do private sector managers? Thus, our goal is to begin determining whether uncertainty classifications that are specific to the public sector are necessary for productive public sector research. We begin with a brief review of extant PEU research. We then present the results of our study of public managers in Hong Kong. Multidimensional scaling (MDS) was used to identify perceived sources and dimensions of uncertainty. Cluster analysis then was used to produce a taxonomy of public sector uncertainty sources. We discuss the implications of the taxonomy for future research on public sector managers and organizations. BACKGROUND The environment’s role has been recognized from at least as early as Frederick Taylor’s time, when he observed a relationship between the environment and the production process (Ashmos & Huber, 1987). Researchers subsequently conceptualized the environment as being comprised of subsets, or domains. Dill’s seminal work, for example, characterized the environment as being comprised of the task domain and the general domain (Dill, 1958). The works of Alchian (1950), Dill (1958), and March and Simon (1958) established that uncertainties associated with domains of the organizational environment should be a major focus of organizational research. Many researchers have attempted to classify the environment into domains that are meaningful for private firms. Duncan identified three internal components and five external components that he theorized could contribute to uncertainty along static-dynamic and simple-complex dimensions (Duncan, 1972). Miles and Snow (1978) developed scales measuring managers’ perceptions of uncertainty in six environmental sectors (i.e., suppliers, customers, financial markets, competitors, labor unions and governmental/regulatory agencies). Likewise, Daft et al. (1988) refined the PEU construct using Dill’s two domains, general and task - along with the specific environmental sectors: competition, customers, technological, regulatory, economic and socio-cultural. Most recently, Priem et al. (2002) had top private sector managers in Hong 4 VOGES, PRIEM, SHOOK & SHAFFER Kong develop a PEU taxonomy that included uncertainties associated with international competitive advantage, industry competition, production costs, human resources, government, and societal change. Researchers debating public and private sector differences have rallied around two positions (Rainey & Boxeman, 2000). The first view, prevalent in the fields of economics and political science, emphasizes the superiority of private sector organizations regarding effectiveness and efficiency. This view emphasizes the differences in public and private sector organizations. The second, contrary view is that the public vs. private sector distinction is only a “crude stereotype”, with organizations in each class having many similar characteristics. This position is more prevalent in the field of organizational theory. The environments faced by public and private sector organizations have been differentiated, however, based on “market” characteristics, cooperation and competition, data availability, political influence, transactions, scrutiny and ownership (Nutt, 1999; Nutt & Backoff, 1993; Rainey, Backoff & Levine, 1976; Willcocks & Currie, 1997). One difference is that public sector organizations often do not operate in competitive markets that provide resources and reimbursements for services rendered (Rainey, Backoff & Levine, 1976). Legitimacy rather than efficiency is often the pivotal element of a public organization (Meyer & Rowan, 1977). A second difference is in the nature of competition. Whereas private sector organizations engage in competition with other companies, organizations in the public sector quite often collaborate with one another. For example, many U.S. state governments are increasingly helping local communities with issues such as education reform. A third difference is that the political influence in the private sector is indirect, whereas public sector organizations often experience direct political influence from authority networks and users. Finally, ownership in the private sector is vested in owners or stockholders whose interests are interpreted using financial indicators. “Owners” of public sector organizations, on the other hand, are citizens who impose a variety of expectations about the organizations’ activities (Perry & Rainey, 1988). Public sector organizations are often subject to intense scrutiny using open records requirements (Nutt, 2000). In spite of these differences, the PEU domains used in studies of organizations in public sector settings often have been the same as the domains developed from private sector studies (e.g., see adaptations of Duncan’s, 1972 instrument that were used in Koberg, 1987, and TAXONOMY OF THE UNCERTAINTY SOURCES PERCEIVED BY PUBLIC SECTOR MANAGERS 5 Milliken, 1990). This generalization of private company uncertainty sources to the public sector is unsatisfactory for several reasons. First, we have little or no evidence that private sector-developed uncertainty classifications are appropriate for public sector organizations. Second, appropriate classification is a prerequisite for effective theory building (McKelvey, 1982). Empirical results based on inadequate classification can find support for “partial theories” at best, and incorrect theories at worst (Pearce, 2001). Third, public sector organizations are assuming greater importance to developed and developing societies. This suggests that more public sector research is warranted. One approach toward improving this situation is to inductively develop a public sector manager-based numerical taxonomy of environmental uncertainty sources, so that public sector research involving PEU can be conducted without introducing the constraints of previously established private sector typologies. The taxonomy development process would identify both the characteristics used by public managers to group similar sources of environmental uncertainty, and the actual classes (i.e., groupings) that result. The goal is progress toward a more up-to-date and empirically grounded framework that ultimately may be helpful for both researchers’ and practitioners’ understandings of uncertainty sources confronting public managers. Our expectation is that public sector managers will perceive at least some different sources of uncertainty than do private sector managers. METHOD AND RESULTS Our field study was conducted in three phases. First, we identified the uncertainty sources seen by public managers, and the underlying dimensions that these managers use to discriminate among sources of uncertainty. The public managers listed all sources of uncertainty facing their organizations, and made similarity judgments that were analyzed using multidimensional scaling techniques (MDS) (Kruskal & Wish, 1978). A benefit of MDS is that the resulting classificatory dimensions, when identified by managers themselves through a non-prompted approach, are less likely to be influenced by researcher presuppositions than are those of approaches such as factor analysis of survey data (Buchko, 1994; Werner & Brouthers, 1996). These dimensions represent the “foundation” on which a taxonomy is based. In the second phase, we validated the MDS results and dimension labels with a second sample of 6 VOGES, PRIEM, SHOOK & SHAFFER public managers. Effective classification of the uncertainty sources by the second sample, based on the dimensions identified by the first sample, increases confidence in the usefulness of the MDS dimensions. This permits continuation to the next step. In the third phase, we inductively derived the managers’ classifications of sources of environmental uncertainty. Although direct visual examination of the graphic results of MDS output can be used to identify similar objects, “great care must be taken when using this technique” to avoid misinterpretation (Hair, Anderson, Tatham & Black, 1998; Jacoby, 1991). We elected to forego the visual approach. Instead, we used the uncertainty source coordinates from the MDS output as input for cluster analyses (Aldenderfer & Blashfield, 1984). This allowed us to group the uncertainty sources based on the managers’ cognitive representations, while minimizing interpretations by the researchers. Our sample, procedures and the rationale for each phase of our study are detailed below. Samples Participants were Executive Officers (EOs) for the Hong Kong government, who were enrolled in a custom-designed graduate course in management at a large Hong Kong university. All held at least an undergraduate degree. EOs are in the “mid-level” general management ranks and are rotated to a new position every 3 years. This helps to ensure that they develop the general management skills necessary for higher level, executive responsibilities. The typical EO supervises between 3 and 50 subordinates; over half are women. Sample 1 consisted of thirty-four EOs, who participated in the first phase of the research. Their ages ranged from 26 to 35 and they had an average tenure of 7.82 years with the Hong Kong government. There were 10 males and 23 females. Thirty-one EOs made up Sample 2, the validation sample. Their ages ranged from 26 to 35 with one over 36 (exclusion of this outlier did not affect our results). They averaged 10.29 years tenure with the Hong Kong government. Nine were males and 22 females. These Hong Kong samples were selected for two important reasons. First, we gathered data from the Hong Kong public managers approximately two months before the scheduled transfer of Hong Kong sovereignty from the United Kingdom to the People’s Republic of China. This turnover period was expected to be one of intense uncertainty over issues such as the rule of law, the type and role of government, business TAXONOMY OF THE UNCERTAINTY SOURCES PERCEIVED BY PUBLIC SECTOR MANAGERS 7 changes and transparency, and individual freedoms (Kahanna, 1995). We considered it vital that we obtain data from public sector managers who were facing a full range of possible sources of uncertainty. This allowed us to develop a public sector PEU taxonomy that is as comprehensive as possible. An effective taxonomy must have a class for every object (McKelvey, 1982). Second, the Hong Kong government provides a variety of public services more common to a country than to a city. In Hong Kong, for example, government organizations supervise a range of activities, including hospitals, housing, the airport, ferries, the central bank, immigration, education, law enforcement, and so on. The EOs in our sample represented each of these areas of government, plus others. Moreover, Hong Kong government will retain control over currency, immigration and foreign relations for a period of fifty years after the transfer of sovereignty. Hence, this sample was particularly likely to identify national-level as well as local level uncertainties facing public organizations, again furthering comprehensiveness. Dimension Identification Phase The Sample 1 managers were first asked “to think about and then develop a comprehensive listing of all the sources of uncertainty facing your department”. They performed this task individually after asking clarification questions. The individual responses were combined across respondents collectively. After redundancies were eliminated, the final list contained 30 PEU sources. Next, a complete set of cards, each of which was labeled with one of the uncertainty sources, was prepared for each study participant. Approximately one week after Step 1, the Sample 1 managers each were given a set of index cards and asked to “group the cards into as many groups as may be necessary to properly reflect the similarities and differences among the uncertainty sources your group identified during the previous session. When you are finished, similar uncertainty sources should be grouped together, while dissimilar sources should be in different groups.” This task was performed individually after asking clarification questions. When satisfied with their groupings, they handed the grouped cards back to the researcher. A 30x30, ½-diagonal matrix for each respondent was then prepared, with “1” entered if two uncertainty sources were placed in the same 8 VOGES, PRIEM, SHOOK & SHAFFER group, and “0” if they were not. These matrices’ values were then aggregated to produce an overall similarities matrix. The matrix was then converted to reflect dissimilarity data “in order to avoid [an] inverse relation between the data values and the geometric model (Jacoby, 1991).” These data were analyzed using the ALSCAL metric MDS program (Young & Lewykcyj, 1979). Solutions were obtained for one, two, three, four, and five dimensions, with stress indices of 0.54, 0.30, 0.17, 0.10 and 0.07 respectively (Kruskal, 1964). The three-dimensional solution exhibited a better fit for our data than did the two-dimensional solution (r2= .83 vs. r2= .62), but the fit improvement leveled off somewhat for four dimensions and even more for five dimensions. We chose the three-dimensional solution for interpretation based on the scree test, on parsimony relative to the four and five dimensional solutions, and on the more likely ease of interpretation (Cattell, 1965; Kruskal & Wish, 1978). Although each manager made up to 400 comparisons of uncertainty sources as input to the MDS, one might question whether 34 public managers, plus the 31-manager validation sample, can be representative of the population of Hong Kong public sector managers. The work of Zaltman and his colleagues is instructive. They have developed a qualitative metaphor elicitation technique (MET) designed to “surface the mental models that drive consumer thinking and behavior” for various topics (Zaltman & Coutler, 1995; Zaltman, 1997). This technique is parallel to the goals in this research: that is, to identify, via nonprompted examination of a relatively small number of participants from a group, the constructs (in our case, classes) used by that group when considering a particular topic area (in our case, uncertainty). Zaltman and Coutler (1995) present data showing that, averaged over several MET projects, it took only six to eight participant files randomlyselected from their 20-person samples to identify 100% of the constructs identified by the entire sample for a particular topic area. This suggests that our more quantitative findings from 34 top managers likely identified the important classes employed by the group “high potential public managers in Hong Kong” when considering the topic “uncertainty”. Generalizability to other groups of public managers remains an empirical question, as we discuss in later sections. To minimize carryover from earlier tasks, we waited approximately one month before asking the Sample 1 managers to label each of the three dimensions they used to distinguish among uncertainty sources. TAXONOMY OF THE UNCERTAINTY SOURCES PERCEIVED BY PUBLIC SECTOR MANAGERS 9 The task was completed first individually and then as a group exercise to derive dimension labels based on consensus. MDS output dimensions represent the degree to which an object represents one characteristic rather than another. Dimensions are frequently labeled based on those objects that appear at the extremes of the dimensions. The managers labeled Dimension One, “Socio-economic”. They used this dimension to distinguish among sources of uncertainty that were related to “external” conditions such as international trade, competition from other economic powers in Asia, and structural changes in the economy, versus “internal” organizational conditions such as privatization of governmental departments, policies and procedures of the government, and the structure and policies of the civil service. The managers labeled Dimension Two, “Political”. They used this dimension to distinguish among sources of uncertainty that were related to “local conditions” such as the influx of immigrants from China, the quality and composition of the Hong Kong population, and public services such as housing, education and welfare, versus “international conditions” such as political instability in other Asian countries, changes in world political systems and direct competition from other cities such as Shanghai and Taipei. The managers labeled Dimension Three, “China’s Influence”. They used this dimension to distinguish among sources of uncertainty that were related to “micro conditions” such as the increasing expectations of Hong Kong residents regarding housing, job security, income equalities, and the public service, versus “macro conditions” such as China’s potential interventions (after the change in sovereignty) in Hong Kong’s economic, social and political systems. The specific reference to China in this dimension is not surprising given the importance of the sovereignty change at the time of our study. This might be thought to restrict application of this dimension to China research only, but that is not the case. Macro political change is an on-going source of potential uncertainty for public managers, as can be seen in Russia, Central and Eastern Europe, and many other locations around the world (Gelb & Tenev, 2000). Even in the U.S., for example, this dimension could distinguish among macro uncertainties generated by a shift from Democratic to Republican control, versus the more micro, customeroriented uncertainties associated with shifting public expectations. Our 10 VOGES, PRIEM, SHOOK & SHAFFER research team relabeled this dimension “Ideological” uncertainty, to enlarge the Hong Kong managers’ more local, “China-specific” label. Dimension Validation Phase In this phase, the Sample 2 managers performed a task designed to validate the three dimensions, and their labels, developed by the Sample 1 managers. First, the Sample 2 managers were given the three dimension labels and descriptions generated by Sample 1, and were asked to position each of the 30 uncertainty sources along each dimension using a five-point scale. Each Sample 2 manager “located” each uncertainty source along each dimension based on his or her understanding of the dimensions and their labels. Next, we used the MDS results for Dimension 1 to identify the ten uncertainty sources with the most extreme MDS scores (i.e. the five at each extreme of Dimension 1). The Sample 2 ratings for these uncertainty sources were then tested for mean differences across the “high-five” and “low-five” Dimension 1 sources. This process was repeated for Dimensions 2 and 3. Significant “high-five” versus “low-five” rating differences were found for each dimension (all p< 0.001). This indicates the dimensions and labels resulting from the first sample were recognized by the second group, and were used successfully to rate uncertainty sources. Still, identifying the underlying dimensions used by public managers in classification does not in itself provide a taxonomy. We turn to that next. Taxonomy Phase The MDS analysis indicated that the Hong Kong public managers distinguish among uncertainty sources by positioning them along dimensions reflecting their socio-economic (internal versus external), political (local versus international) and ideological (micro versus macro) natures. Given the three-dimension MDS solution, if each dimension were split at the mean and combined in a 3-dimensional cube there would be eight possible categories of uncertainty sources. It is not clear, however, whether or not each possible cell would actually contain an uncertainty source. Clustering the uncertainty sources using the MDS output (i.e., the 3 coordinates for each uncertainty source) allowed us to identify which categories actually are meaningful to the public managers, and to achieve a more parsimonious classification system. TAXONOMY OF THE UNCERTAINTY SOURCES PERCEIVED BY PUBLIC SECTOR MANAGERS 11 Clustering results are subject to researcher judgment, as well as to the inherent biases associated with clustering algorithms (Aldenderfer & Blashfield, 1984). We recognize these limitations of cluster analysis, and chose to use a dual-stage clustering method to increase the validity of the solution (Milligan, 1980; Punj & Stewart, 1983). Following the recommendations of Ketchen and Shook (1996), we first evaluated the correlations among the three dimensions. These ranged from -.06 to .10, indicating the absence of multi-collinearity. Second, a hierarchical, agglomerative clustering algorithm (Ward’s minimum variance technique) generated a tentative cluster solution and indicated the number of clusters. The r-squared (.86) and CCC (2.94) of the Ward’s output suggested a six-cluster solution (Everett & Der, 1996). Third, a second cluster analysis was generated using the first analysis’ cluster means as the initial conditions for an iterative, point kernel procedure (kmeans clustering). The two cluster procedures use extremely dissimilar algorithms and approaches to clustering (Aldenderfer & Blashfield, 1984). There was strong agreement across these very different clustering techniques; twenty-nine of the thirty PEU sources were classified in the same clusters for both the Ward’s and k-means analyses. This increases confidence in the reliability of the cluster solution. We labeled the clusters based on the PEU sources they contained. For instance, the first cluster contained uncertainty sources such as economic structure changes, the property market and technological changes. We labeled this cluster “Techno-economic Conditions”. The resulting clusters and their labels are shown in Table 1. To illustrate where each cluster is positioned along the distinguishing dimensions, Figure 1 provides a three-dimensional representation of cluster centroids and their coordinates. DISCUSSION The taxonomic results of our study provide an answer for our first research question, What are the sources of uncertainty perceived by public sector managers? The six uncertainty source groups shown in Table 1 result from three distinct dimensions that were used by the Hong Kong public managers in classifying uncertainties. These dimensions included a political dimension (rated as local versus international), a socio-economic dimension (rated as internal organizational versus 12 VOGES, PRIEM, SHOOK & SHAFFER external), and an ideological dimension (rated as micro versus macro conditions). Our second research question, Do public sector managers perceive the same uncertainties as do private sector managers?, can be examined by comparing our public sector PEU taxonomy with other PEU taxonomies and typologies. TABLE 1 A Taxonomy of Public Managers’ Perceived Uncertainties Cluster 1: Techno-economic conditions Economic structure changes Property market Technological changes Cluster 2: Internal organizational conditions Laws governing work procedures Continuity/succession of senior government officials HK government finances - sources /allocation Policies/procedures of the government Structure/policies of civil services Privatization of government departments Management style of HK officials Use of Chinese language Appointment of PRC officials to government posts Cluster 3: International politics and competition Political instability in other Asian countries Changes in world political systems Competition from other economic powers in Asia International trade Competition from other cities such as Shanghai and Taipei Cluster 4: Local population characteristics Influx of unskilled cheap labor from China Corruption and bribery Brain drain Quality and composition of the HK population Influx of immigrants from China Cluster 5: Governmental Influence China’s influence after change in sovereignty 30 June 1997 Intervention by China on Hong Kong economic and social system Political instability in Hong Kong Modification of the legal system TAXONOMY OF THE UNCERTAINTY SOURCES PERCEIVED BY PUBLIC SECTOR MANAGERS 13 Cluster 6: Societal expectations Increasing expectations of Hong Kong residents regarding housing, welfare Public services: housing, education, welfare Job security Income Imbalance FIGURE 1 Public Managers’ Perceived Uncertainty Clusters 3 2.0 1.0 5 1 Pol itical 2 0.0 4 -1.0 2.0 1.0 0.0 Ideo logical -1.0 Cluster Label 1. Techno-economic conditions 2. Internal organizational conditions 3. International politics and competition 4. Local populations characteristics 5. Governmental influence 6. Societal expectations 6 -1.0 Socioeconomic 1.31 -1.61 1.21 .70 .48 -.20 0.0 1.0 2.0 Soc io-eco nomic Dimension Political Ideological .01 .19 1.69 -.66 .08 -.17 -1.27 .03 -.99 .27 1.33 -1.14 Table 2 summarizes the similarities and differences among our public sector PEU taxonomy, three well-known U.S. private sector 14 VOGES, PRIEM, SHOOK & SHAFFER typologies, and the recent Priem et al. (2002) Hong Kong private sector PEU taxonomy. Societal uncertainties are common to all five of these classification schemes. Organizational conditions, economic, and technological uncertainties are common to the pubic sector taxonomy, as well as to two of the four other private sector taxonomies. These similarities indicate that private sector and public sector uncertainties are not totally different. This result is not unexpected, and it provides further validation of our taxonomy. TABLE 2 External Governmental Influence International Politics and Competition Political Industry Competition Economic Societal Technological Regulatory Customers Suppliers Public Sector Taxonomy Daft, Sormunen and Parks (1988) X Priem, Love and Shaffer (2002) Internal Organizational Conditions Miles and Snow (1978) Duncan (1972) Comparison of PEU Classification Systems X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X X There clearly are important differences that need to be recognized, however, between the private sector typologies and our public sector taxonomy. Our taxonomy focuses on political and broad ideological sources of PEU that are ignored by the other classification schemes (Daft et al., 1988; Duncan, 1972; Miles & Snow, 1978; Priem et al., 2002). This focus is evident in that there are cluster categories for 1) TAXONOMY OF THE UNCERTAINTY SOURCES PERCEIVED BY PUBLIC SECTOR MANAGERS 15 governmental influence and 2) international politics and competition in the public sector taxonomy that are not evident in any of the three wellknown taxonomies, nor in the recent parallel private sector Hong Kong study. Further, the political cluster category in the public sector taxonomy is only found in the Duncan taxonomy. The public sector taxonomy also includes uncertainties internal to the organization, and previously unobserved international uncertainty sources. Of the three well-known taxonomies, only Duncan identified internal organizational sources. Interestingly, the recent Priem et al. (2002) private sector study also identified internal sources. All three taxonomies (e.g. Duncan’s, our public sector taxonomy and the Priem et al. work) utilized a methodology in which managers provided the sources of uncertainty. This contrasts with the Miles and Snow (1978) and Daft et al. (1988) typologies, which were derived from previous studies’ research constructs. On the other hand, our public sector taxonomy does not include the customer and supplier uncertainties that are common in the well-known private sector typologies. Thus, the answer for our second research question is that for some classes of uncertainty the answer is yes, there are similarities between public sector and private sector uncertainty sources; for others, no. The divergence between our public sector, manager-generated taxonomy of uncertainty sources and the existing, private sector typologies may be the result of two factors. The first is simply that the concerns and challenges of public and private sector managers are different. This explanation supports the view that there are important differences between public and private organizations (Rainey & Bozeman, 2000). A second possible explanation is that increasing globalization adds more uncertainties to almost any organizational type (Porter, 1990). For example, the opening of trade through accords such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the European Community (EC), likely added potential sources of uncertainty. This could contribute to divergence from the well-known private sector uncertainty typologies because they were developed quite long ago. This explanation is further supported in the observation that the recent parallel study recognizes the international sources. Our findings provide a number of opportunities for extending theory and research relating PEU to managerial action in the public sector. First, the taxonomy creates meaningful patterns in a plethora of 16 VOGES, PRIEM, SHOOK & SHAFFER uncertainty sources facing public managers. It provides a comprehensive yet parsimonious classification that can contribute to theory building. The introduction of international political uncertainty sources and the inclusion of previously little-considered internal organizational uncertainty sources, when combined with the further specification of political, ideological, and societal sources, provide a first step toward enhancing our ability to build and test theories of action for public sector managers. One might argue, for example, that public managers’ attention to uncertainty sources associated with international politics and competition will be greater in countries where a higher percentage of GDP is involved in international trade. Or, one might argue that public managers whose governments are planning privatizations will pay more attention to uncertainties from internal organizational conditions. Second, our study contributes empirical evidence to the publicprivate sector debate. The taxonomy provides general evidence to caution researchers about the potential danger of using private sector classifications for public sector work. It also indicates that Meyer’s concerns about theoretical overgeneralization if the public-private distinction is blurred may be well founded (Meyer, 1982). Our PEU taxonomy contains uncertainty sources that are unique to public sector managers. Thus, it may help researchers to establish previously unconsidered relationships between the environment and the activities of public sector managers. Future inclusion of uncertainty due to potential ideological changes, for example, could improve our understanding of how public managers define and clarify goals in their organizations. Third, the taxonomy may facilitate research to expand knowledge of differences in the relationships between PEU and organizational action in public and private sector contexts. One might examine, for example, across public and private contexts: 1) whether relationships among similar variables are different, and 2) whether the causally important variables themselves differ. Our study has a number of limitations based on the inherent research tradeoffs among simplicity, accuracy and generalizability (Weick, 1969). First, in spite of its many advantages noted in the Method and Results section, ours was a small, convenience sample. The possibility exists that unique Hong Kong factors influenced the uncertainty classifications. Thus, the representativeness of our taxonomy for public organizations worldwide remains to be confirmed through replication. Second, although major political changes are prevalent in large portions of the TAXONOMY OF THE UNCERTAINTY SOURCES PERCEIVED BY PUBLIC SECTOR MANAGERS 17 world, it is possible that managers in a more stable public sector setting could face an uncertainty source that cannot be classified via our taxonomy (May, Stewart & Sweo, 2000). We contend, however, that use of a PEU source classification that captures the multiplicity of political, ideological, societal and organizational uncertainty sources is more likely to generate meaningful public sector research results than would continued use of private sector based classification schemes. Finally, although we made efforts to exclude researcher bias through our methodology, it is impossible to rule it out conclusively. The managers developed lists of all sources of uncertainty, but our judgment was required to aggregate the lists and eliminate redundancies. Moreover, the managers labeled the dimensions, but we labeled the clusters. The threat of unintended bias may be less likely, however, due to the validation of the MDS results using a different data collection method and a different public manager sample. CONCLUSION Venkatraman and Grant (1986) note that well-defined constructs are a basic criterion for the interpretation of substantive relationships. Perry and Rainey argue that organizational theory can advance only through properly distinguishing between public sector and private sector organizations (1988). These arguments were made 15 years ago, but little progress has been made since then toward either defining a public sector PEU construct or distinguishing it from private sector PEU. Yet uncertainty is a central concept in theories of public and private organizations. We hope that the practitioner-derived taxonomy of public sector PEU sources identified by our research responds to each of these requirements - that it 1) contributes to a better defined uncertainty sources construct for the public sector, and 2) helps to further distinguish between public and private sector organizations along the critical uncertainty variable. Despite a “blurring” of boundaries between public and private sector organizations due to activities such as privatization, there is a continuing need to distinguish between these two organization types (Bryson, 1995). This taxonomy suggests that public sector and private sector managers perceive differing sources as generating uncertainty for their organizations. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 18 VOGES, PRIEM, SHOOK & SHAFFER We thank Howard Balanoff, Vince Barker, Dave Ketchen, Paul Nystrom, Abdul Rasheed and Masoud Yasai-Ardekani for helpful comments. REFERENCES Alchian A.A. (1950). “Uncertainty, Evolution and Economic Theory,” The Journal of Public Economics, 58, 211-221 Aldenderfer, M.K. & Blashfield, R.K. (1984). Cluster Analysis. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications. Aldrich, H. & Pfeffer, J. (1976). “Environments of Organizations,” Annual Review of Sociology, 2, 79-105. Ashmos, D.P., & Huber, G.P. (1987). “The Systems Paradigm in Organizational Theory: Correcting the Record and Suggesting the Future,” Academy of Management Review, 12, 607-621. Bryson, J.M. (1995). Strategic Planning for Public and Nonprofit Organizations: A Guide to Strengthening and Sustaining Organizational Achievement. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Buchko, A.A. (1994). “Conceptualization and Measurement of Environmental Uncertainty: An Assessment of the Miles and Snow Perceived Environmental Uncertainty Scale,” Academy of Management Journal, 37, 410-425. Cattell, R. (1965). Handbook of Multivariate Experimental Psychology. Chicago, IL: Rand-McNally. Daft, R.L., Sormunen, J., & Parks, D. (1988). “Chief Executive Scanning, Environmental Characteristics, and Company Performance: An Empirical Study,” Strategic Management Journal, 9, 123-139. Dill, W.R. (1958). “Environment as an Influence on Managerial Autonomy,” Administrative Science Quarterly, 2, 409-443. Duncan, R. (1972). “Characteristics of Organizational Environments and Perceived Environmental Uncertainty,” Administrative Science Quarterly, 17, 313-327. Everett, B.S., & Der, G. (1996). A Handbook of Statistical Analyses Using SAS. London: Chapman and Hall. TAXONOMY OF THE UNCERTAINTY SOURCES PERCEIVED BY PUBLIC SECTOR MANAGERS 19 Galaskiewicz, J., & Bielfeld, W. (1998). Nonprofit Organizations in an Age of Uncertainty: A Study of Organizational Change. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine de Gruyter. Gelb, A. & Tenev. S. (2000). “Circumstances and Choice: The Role of Initial Conditions and Policies in Transition Economies,” The World Bank Economic Review, 15, 1-31. Gioia, D.A. & Thomas, J.B. (1996). “Identity, Image, and Issue Interpretation: Sensemaking During Strategic Change in Academia,” Administrative Science Quarterly, 41, 370-403. Hair, Jr. J.F., Anderson, R.E., Tatham, R.E., & Black, W.C. (1998). Multivariate Data Analysis. Upper Saddle, NJ: Prentice Hall, Inc. Hofer, C.W. (1975). “Toward a Contingency Theory of Business Strategy,” Academy of Management Journal, 18, 784-801. Jacoby, W.G. (1991). Data Theory and Dimensional Analysis. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. Katz, D., & Kahn, R.L. (1978). The Social Psychology of Organizations. New York: John Wiley and Sons. . Ketchen, D.J. & Shook, C.L. (1996). “The Application of Cluster Analysis in Strategic Management Research: An Analysis and Critique,” Strategic Management Journal, 17 (6), 441-458. Khanna, J. (1995). Southern China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan: Evolution of a Subregional Economy. Washington DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies. Koberg, C. (1987). “Resource Scarcity, Environmental Uncertainty and Adaptive Organizational Behavior,” Academy of Management Journal, 30, 798-807. Kruskal, J. (1964). “Multidimensional Scaling by Optimizing Goodness of Fit to a Monothetic Hypotheses,” Psychometrika, 29, 1-27. Kruskal, J. &. Wish. M. (1978). Multidimensional Scaling. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications. Lant, T.K., Milliken, F.J., & Batra. B. (1992). “The Role of Managerial Learning and Interpretation in Strategic Persistence and 20 VOGES, PRIEM, SHOOK & SHAFFER Reorientation: An Empirical Exploration,” Strategic Management Journal, 13, 585-608. March, J.G. & Simon, H.A. (1958). Organizations. New York: Wiley. May, R.C. Stewart, W.H., & Sweo, R. (2000). “Environmental Scanning Behavior in a Transitional Economy: Evidence from Russia,” Academy of Management Journal, 43(3), 403-426. McKelvey, W. (1982). Organizational Systematics: Taxonomy, Evolution, Classification. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. Meyer, M.W. (1982). “‘Bureaucratic’ vs. ‘Profit’ Organization.” In Staw, B.M. & Cummings, L.L. (Eds.), Research in Organizational Behavior (pp. 89-126). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Meyer, J.W., & Rowan, B. (1977). “Institutionalized Organizations: Formal Structure As Myth and Ceremony,” American Journal of Sociology, 83, 340-363. Miles, R.E., & Snow, C.C. in collaboration with Meyer, A.D., and with contributions by Coleman, H.J. Jr. (1978). Organizational Strategy, Structure and Process. New York: McGraw-Hill. Milligan, G.W. (1980). “An Examination of the Effect of Six Types of Error Perturbation on Fifteen Clustering Algorithms,” Psychometrika, 45, 325-342. Milliken, F.J. (1990). “Perceiving and Interpreting Environmental Change: An Examination of College Administrators’ Interpretation of Changing Demographics,” Academy of Management Journal, 33, 42-63. Nutt, P. (1999). “Public-Private Differences and Assessment of Alternatives for Decision Making,” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 9, 305-349. Nutt, P. (2000). “Decision Making Success in Public, Private and Third Sector Organizations: Finding Sector Dependent Best Practices,” Journal of Management Studies, 37, 77-108. Nutt, P., & Backoff, R.W. (1993). “Organizational Publicness and its Implications for Strategic Management,” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 3, 182-201. TAXONOMY OF THE UNCERTAINTY SOURCES PERCEIVED BY PUBLIC SECTOR MANAGERS 21 Pearce, J.L. (2001). Organization and Management in the Embrace of Government. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Perry, J.L., & Rainey, H.G. (1988). “The Public-Private Distinction in Organization Theory: A Critique and Research Strategy,” Academy of Management Review, 13, 182-201. Porter, M.E. (1990). The Competitive Advantage of Nations. New York: Free Press. Priem, R.L., Love, L., & Shaffer, M. (2002). “Executive’s Perceptions of Uncertainty Sources: A Numerical Taxonomy and Underlying Dimensions,” Journal of Management, 28, 725-747. Punj, G., & Stewart, D.W. (1983). “Cluster Analysis in Marketing Research: Review and Suggestions for Application,” Journal of Marketing Research, 20, 134-148. Rainey, H.G., Backoff, R.W., & Levine, C.H. (1976). “Comparing Public and Private Organizations,” Public Administration Review, 36, 233-244. Rainey, H.G., & Bozeman, B. (2000). “Comparing Public and Private Organizations: Empirical Research and The Power of the A Priori,” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 10, 447-469. Thomas, J.B., Clark, S.M., & D.A.Gioia. (1993). “Strategic Sensemaking and Organizational Performance: Linkages among Scanning, Interpretation, Action and Outcomes,” Academy of Management Journal, 3, 239-270. Venkatraman, N., & Grant, V. (1986). “Construct Measurement in Organizational Strategy Research: A Critique and Proposal,” Academy of Management Review, 11 (1), 71-87. Weick, K.E. (1969). The Social Psychology of Organizing. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. Werner, S., & Brouthers, L.E. (1996). “International Risk and Perceived Environmental Uncertainty: The Dimensionality and Internal Consistency of Miller’s Measure,” Journal of International Business Studies, 27, 571-588. 22 VOGES, PRIEM, SHOOK & SHAFFER Willcocks, L.P., & Currie, W.L. (1997). “Information Technology in Public Services: Towards the Contractual Organization?” British Journal of Management, 8, 107-120. Yasai-Ardekani, M., & Nystrom, P.C. (1996). “Designs for Environmental Scanning Systems: Tests of Contingency Theory. Management Science, 42, 187-204. Young, F.W., & Lewykcyj, R. (1979). ALSCAL-4: User’s Guide. Chapel Hill, NC: Psychometric Laboratory, University of North Carolina. Zaltman, G. (1997). “Rethinking Marketing Research: Putting People Back in,” Journal of Marketing Research, 34, 424-437. Zaltman, G., & Coutler, R.H. (1995). “Seeing the Voice of the Customer: Metaphor-Based Advertising Research,” Journal of Advertising Research, 35, 35-51.