Supplementary Information - QIMR Genetic Epidemiology

advertisement

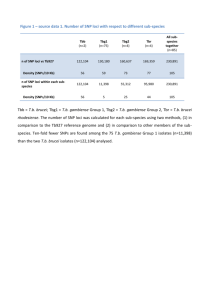

Supplementary Information Common SNPs Explain Some of the Variation in the Personality Dimensions of Neuroticism and Extraversion Anna AE Vinkhuyzen, PhD1,8,9, Nancy L Pedersen, PhD2, Jian Yang, PhD1, S. Hong Lee, PhD1,8, Patrik KE Magnusson, PhD2, William G Iacono, PhD3, Matt McGue, PhD3, Pamela AF Madden, PhD4, Andrew C Heath, PhD 4, Michelle Luciano, PhD5, Antony Payton, PhD 6, Michael Horan, PhD7, William Ollier, PhD6, Neil Pendleton, PhD 7, Ian J Deary, PhD5, Grant W Montgomery, PhD1, Nicholas G Martin, PhD1, Peter M Visscher, PhD1, Naomi R Wray, PhD1,8 1 Queensland Institute of Medical Research, Brisbane, Australia 2 Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden 3 Department of Psychology, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA 4 Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri, USA 5 Centre for Cognitive Ageing and Cognitive Epidemiology, Department of Psychology, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK 6 Medical Genetics Section, University of Edinburgh Molecular Medicine Centre, Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, Western General Hospital, Edinburgh, UK 7 School of Medicine, The University of Manchester, Manchester, UK 8 The University of Queensland, Queensland Brain Institute, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia 9 To whom correspondence should be addressed at: The University of Queensland, Queensland Brain Institute (building #79), St Lucia, 4072, Queensland, Australia, Phone: +61 7 3346 6430, Fax: +61 7 3346 6301, Email: anna.vinkhuyzen@uq.edu.au CONTENTS: Section 1: Supplementary Notes: - Description of samples and phenotypes - Description of the analyses Section 3: Supplementary Tables 1-3 Section 4: Supplementary Figures 1-2 Supplementary Information: Section 1 Description of samples, phenotypes, and quality control. Samples and phenotypes Neuroticism and Extraversion scores were derived from the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (EPQ)1, 2, the NEO-Five Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI)3, the International Personality Item Pool (IPIP)4, 5, and the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire (MPQ)6, 7, see below for details. Each scale uses a sum score of binary item responses. To normalize sum scores on the EPQ Neuroticism and Extraversion scales, an averaged angular transformation 8 was applied to the raw sum scores (y) separately for each sub sample, with n the total number of items. Residuals were derived from regression of the (transformed) Neuroticism and Extraversion sum scores on sex, age, sex*age, age2, and sex*age2; residuals were then standardized separately for each sex and combined over all cohorts generating the phenotypic value used in the linear model (see Analyses section below). Cohort membership was included as a fixed effect in the model. Individuals with scores above or below 3 SD from the mean were removed (36 individuals for Neuroticism, 20 individuals for Extraversion). Australia Australian data were derived from twin- and family studies that were conducted at different points in time at the Queensland Institute of Medical Research (QIMR)9-12. Neuroticism was measured in ~1980 (EPQ-23-items: N=2947), ~1989 (EPQ-12-items; N=2871), and ~2002 (NEO-FFI-12-items; N=213). Extraversion was measured in 1980 (EPQ-21-items; N=2906) and 1989 (EPQ-12-items, N=2839). Data collection and cohort description of the 1980 and 1989 waves of data collection are described in more detail by Birley et al.11, and the data collection and sample description of the 2002 collection are described by Saccone et al.12. If EPQ data were available from more than one time point, data from 1980 were retained because this data set was based on the full EPQ rather than the abridged version used in 1989. If individuals had data on both EPQ and NEO, EPQ data were retained. After QC, genotype and phenotype data were available for 6031 (63% female) and 5745 (63% female) participants for Neuroticism and Extraversion, respectively. Sweden Neuroticism and Extraversion data were collected within the middle cohort of the Swedish Twin Registry13 between 1972 and 1973, using the EPQ-9-items14 for both scales. After QC, genotype and phenotype data for Neuroticism and Extraversion were available for 5794 (54% female) and 5748 (54% females) participants, respectively. United Kingdom Data from the United Kingdom (UK) were derived from four different cohorts: the Newcastle and Manchester cohorts15 and the 1921 and 1936 Lothian Birth Cohorts (LBC1921 and LBC1936, respectively)16-18. Neuroticism was measured using the EPQ-23-items in the Newcastle and Manchester cohorts, the IPIP-10-items in LBC1921, and the NEO-12-items in the LBC1936. Please note that Neuroticism in the IPIP is measured as Emotional Stability, reverse scores were used for the analyses. Extraversion was measured using the EPQ-21-items in the Newcastle and Manchester cohorts, the IPIP10-items in LBC1921, and the NEO-12-items in the LBC1936. Neuroticism data were available for 687 (72% female), 593 (73% female), 395 (60% female), and 867 (51% female) individuals from the Newcastle, Manchester, LBC1921, and LBC1936 cohorts, respectively. Extraversion data were available for 686 (72% female), 593 (73% female), 408 (60% female), and 870 (51% female) individuals from the Newcastle, Manchester, LBC1921, and LBC1936 cohorts, respectively. All individuals were genotyped and passed QC. United States of America Neuroticism and Extraversion data were collected as part of three ongoing studies at the Minnesota Center for Twin and Family Research (MCTFR; Iacono & McGue, 2002) in which a 198-item version of the MPQ was administered. The three studies are: The Minnesota Twin Family Study (MTFS), a longitudinal study of adolescent twins and their parents19; The Sibling Interaction and Behavior Study (SIBS), a longitudinal study of adolescent adopted and biological full siblings and their rearing parents20; and The Enrichment Study (ES), a longitudinal study of adolescent twins selected to be at high risk for externalizing psychopathology and their parents21. Details concerning the genotyping of the MCTFR sample, including quality control filters on samples and markers can be found in elsewhere22. For the present study, the MPQ higher-order Negative Emotionality scale was used for Neuroticism and the MPQ higher-order Positive Emotionality scale was used for Extraversion; after QC genotype and phenotype data were available for spouse pairs in the parent generation of the respective studies: 3508 (55% female) and 3507 (55% female) participants, respectively. Combined sample: For the combined sample, data from 17875 (58% female) individuals were available for Neuroticism (mean age 39.07; SD=16.02, range: 14-86). After estimation of the pairwise genetic similarity using all autosomal markers, 11961 (58% females) individuals were retained (mean age 42.36; SD=16.91, range: 14-86). For Extraversion, data from 17557 individuals (59% female) individuals were available (mean age 39.01; SD=16.18, range: 14-86) of whom 11786 (58% females) were genetically ‘unrelated’ (mean age 42.36; SD=17.09, range: 14-86). Genotyping and quality control Samples from the UK (Newcastle, Manchester, LBC1921, and LBC1936), Minnesota, and Sweden were genotyped on the Illumina610-Quadv1 chip, Illumina 660W Quad array, and the Illumina OmniExpress 700K respectively. Samples from Australia were genotyped on an Illumina SNP microarray chip at different genotype centres using different platforms (317K, 370K-array, 370-Quad, 610-Quad, and humanCNV370-Quadv3). Detailed information on genotyping and quality control (QC) can be found elsewhere 22-25. In brief, QC procedures were applied separately to each individual cohort. Individuals with a call rate <0.95 (N=22), estimated inbreeding coefficient > 0.15 (N=2)26, and individuals showing evidence of nonEuropean descent from multidimensional scaling (N=298, mainly individuals from the USA cohort with Mexican ancestry) were removed. Individuals were considered outlying from European descent if one or more of the first four eigenvectors were more than 3SD removed from the mean. SNPs with minor allele frequency (MAF) < 0.01, call rate < 0.95 or Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium test p-value <0.001 were removed. After QC, a total of 18009 individuals (before removing ‘related’ individuals) with data on Neuroticism and/or Extraversion remained. A total of 849,801 autosomal SNPs and 21,187 X chromosomal SNPs were retained across all cohorts. These numbers refer to all the SNPs that met the QC criteria within each project but were not necessarily genotyped in all cohorts. 162,056 autosomal SNPs were in common across all cohorts. See Supplementary Table S2 for number of SNPs included in specific analyses. Description of the analyses The method applied in the present study is extensively described by Yang et al.26, 27 and is designed to capture variation due to linkage disequilibrium between genotyped SNPs and unknown causal variants in the genome. This estimate of variance explained by all SNPs is different from heritability estimates in twin- and family studies as the latter include variance explained by all causal variants (an estimate of the latent genetic effect). We first estimated the pair wise genetic similarity between all the 18009 individuals that were included in the present study cohorts using all autosomal markers that passed QC procedures. We selected a subset of ‘unrelated’ individuals (pair-wise genetic similarity at less than 0.025, approximately corresponding to 2nd cousins) for further analyses to ensure that the estimate of variance explained by common SNPs is not driven by common environmental effects (e.g., non-genetic familial effects) and causal variants not tagged by SNPs but captured by pedigree information. The related individuals were removed selectively, rather than at random, to maximize the remaining sample size 26. We also created a set of ‘unrelated’ individuals in each cohort for the analyses in individual cohorts (See Supplementary Table S2). To estimate the variance explained by the SNPs, a linear model was fitted to the data in which the SNP effects variance . The linear model for an individual is the effect of the the SNP were treated as random variables from a distribution with SNP, with where is the phenotypic value, the allele frequency and is the genotype indicator of , and is a random environmental effect including measurement error. In matrix notation, the linear model for all individuals is y = g + e, where var(y) = A σ2b + I σ2e, and A is the matrix of genome-wide similarities between individuals (i.e., genetic similarity estimated from all the SNPs). We used the following equation to calculate the genetic similarity between individuals j and k: , where m is the number of SNPs. We first fitted the linear model including all autosomal SNPs to estimate the proportion of the variance explained by all the SNPs. Cohort status and the first 20 principal components (PC) from a principal component analysis were fitted as covariates in the model to control for the effects attributable to population structure. Analyses were repeated (i) without PC adjustment, (ii) adjusting for imprecise LD between genotyped SNPs and causal variants (See notes Supplementary Table 2 for details), (iii) separately for each cohort, (iv) for the total sample excluding one cohort at a time, (v) fitting only SNPs on the X chromosome; (vi) separately for men and women, and (vii) including a genotype-by-sex interaction term. To investigate whether the variance explained is proportional to the length of the chromosome, we subsequently partitioned the variance explained into individual autosomes28. To this end, all chromosomes were simultaneously fitted in a mixed linear model and the proportion of the variance explained by each of the chromosomes was estimated. In a subsequent series of analyses we investigated possible discrepancy in the percentage of variance explained by SNPs and variance explained by twin-and family studies. We mimicked the conventional AE-model (i.e., estimation of additive genetic factors and environmental factors) using the entire Australian sample including close. The sample consisted of 3075 families with genotype and phenotype data from 5973 individuals among which 4168 twins (922 complete MZ twin pairs, 619 complete DZ twin pairs), 1365 siblings, and 248 parents of the twins and siblings (115 complete pairs). In twin and family studies, estimates of heritability are based on the relationship between phenotypic resemblance and expected genetic similarity based on pedigree information (e.g., MZ twin pairs are expected to share 100% of their genetic material whereas DZ twins, full sibs and parent-offspring pairs are expected to share 50% of their genetic material). SNP data, however, provide us with estimates of the realized genetic similarity, which vary around the expected values from pedigrees (See Figure S2). The genetic variation around the expected values (e.g., 0%, 50% or 100%) is not captured by pedigree studies but can be captured by the SNP data. In order to estimate the variance that is explained by SNP data, additional to the variance explained by pedigree data, two genetic similarity matrices were created: one based on SNP data (the realized genetic similarity, similarity, ) and the other based on pedigree information (the expected genetic ). From the SNP model above, we know that the covariance between the phenotypes of individuals j and k is , with the total genetic effect of the causal variants tagged by SNPs 27, 29. This model is exactly analogous to using pedigree information where the covariance between individuals j and k from the pedigree matrix is . The analysis consisted of seven steps: (1) Estimation of variance explained by all SNPs based on ‘unrelated’ individuals using genome wide SNP data, as above. (2) Estimation of variance explained by all SNPs based on all individuals, again using genome wide SNP data. In this situation, the estimate of variance explained by all SNPs is dominated by the close relatives and it is expected to be similar to heritability estimates reported by twin and family studies. (3) Estimation of heritability based on all individuals using expected genetic similarity (pedigree similarity matrix). The estimates based on all individuals from the SNP similarity matrix (step 2) and the pedigree similarity matrix (step 3) are expected to be highly correlated. However, observed similarity deviates from expected similarity and SNP-based similarity include information of genetic similarity between distant relatives not known through recorded pedigree information. (4) Partitioning of the variance onto variance captured by the SNP similarity matrix and variance captured by the pedigree similarity matrix. The linear model is such that the covariance between knowingly related individuals j and k is and the covariance between not knowingly related individuals is . Partitioning the variance gives estimates of variance explained by the pedigree similarity matrix and variance that is additionally explained by the SNP similarity matrix. This additional variance is due to variation around the expected values of similarity for ‘related’ individuals (i.e., expected genetic similarity e.g. > .025 in the SNP matrix) and to variation in genetic similarity of ‘unrelated’ individuals (i.e., expected genetic similarity e.g. < .025 in the SNP similarity matrix). (5) Variance was then partitioned further into variance captured by the pedigree similarity matrix, and by SNP similarity matrices, one for ‘unrelated’ individuals and one for ‘related' individuals, in order to distinguish between variation around expected values of ‘unrelated’ and ‘related’ individuals. Off-diagonal entries in the matrices for similarity between the ‘unrelated’ and ‘related’ individuals were set to zero. Initially, the threshold for ‘unrelated’ was set at .025, the analyses were repeated using thresholds for ‘unrelated’ of .1 (analysis 6) and .2 (analysis 7) from the SNP similarity matrix, rather than 0.025, to account for imprecise estimation of identity by state coefficients for distant relatives and to preserve higher similarity between the pedigree similarity matrix and the SNP similarity matrices. Pairs of individuals that showed discrepancies in their genetic similarity between pedigree matrix and SNP matrix larger than .2 were removed (N individuals removed = 83). Discrepancies are likely to occur if individuals have unknown common ancestry because of missing founders in the pedigree similarity matrix, a type of missingness that generally occurs in population based human data. For example, a pair of individuals with unknown common ancestors is regarded as unrelated in the pedigree matrix, while estimate of genetic similarity from SNP data indicates that they are likely to be close relatives. Section 3: Supplementary Tables Supplementary Table S1. Number of participants (% females), mean age (standard deviation), and phenotype information for each cohort and for the total sample. Neuroticism All individuals N (% females) Sweden USA UK-Newcastle UK-Manchester UK-LBC1921 UK-LBC1936 Australia Total Extraversion 5794 (54%) 3508 (55%) 687 (72%) 593 (73%) 395 (60%) 867 (51%) 6031 (63%) 17875 (58%) Sweden USA UK-Newcastle UK-Manchester UK-LBC1921 UK-LBC1936 Australia Total Mean age (SD) N (% females) 29.67 (7.78) 43.59 (5.60) 65.86 (6.00) 64.58 (6.10) 81.15 (0.29) 69.53 (0.85) 32.51 (11.86) 39.07 (16.02) All individuals N (% females) 5748 (54%) 3507 (55%) 686 (72%) 593 (73%) 408 (60%) 870 (51%) 5745 (63%) 17557 (59%) ‘Unrelated’ individuals 3268 (53%) 3264 (56%) 671 (71%) 586 (73%) 373 (59%) 822 (51%) 2977 (62%) 11961 (58%) 29.73 (7.86) 43.57 (5.62) 65.86 (5.99) 64.58 (6.09) 81.15 (0.29) 69.53 (0.86) 32.87 (12.26) 42.36 (16.91) Questionnaire (number of items) EPQ (9) MPQ EPQ (23) EPQ (23) IPIP (10) NEO (12) EPQ (23,12)*/NEO (12)** ‘Unrelated’ individuals Mean age (SD) N (% females) 29.68 (7.78) 43.57 (5.59) 65.87 (5.98) 64.58 (6.10) 81.15 (0.29) 69.53 (0.85) 31.83 (11.84) 39.01 (16.18) Mean age (SD) 3235 (53%) 3261 (56%) 670 (71%) 586 (73%) 385 (58%) 824 (51%) 2825 (63%) 11786 (58%) Mean age (SD) 29.75 (7.85) 43.57 (5.61) 65.88 (5.97) 64.58 (6.09) 81.15 (0.29) 69.53 (0.85) 32.00 (12.23) 42.36 (17.09) EPQ (9) MPQ EPQ (21) EPQ (21) IPIP (10) NEO (12) EPQ (21,12)* Notes: Numbers refer to the sample including All Individuals (left panel) and the sample including ‘Unrelated’ Individuals, i.e., individuals with a pairwise genetic similarity < 0.025 (middle panel); N=number of individuals; SD = standard deviation; USA = United States of America; UK = United Kingdom; LBC1921 = 1921 Lothian Birth Cohort; LBC1936 = 1936 Lothian Birth Cohort; Numbers refer to number of individuals for whom genotype data are available (after QC); EPQ = Eysenck Personality Questionnaire; MPQ = Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire Scales (MPQ scales are higher-order scale scores and are a function of the other MPQ scales); IPIP = International Personality Item Pool; NEO = Neuroticism-Extroversion-Openness Five-Factor-Inventory; for each questionnaire used, the number of items is shown between brackets; *in case individuals EPQ data were available for the full and abridged version of the EPQ, data from the full version were used for the analyses; **if individuals had data on both EPQ and NEO, EPQ data were retained. Supplementary Table S2 Proportion of variance explained by autosomal SNPs for Neuroticism and Extraversion Neuroticism Total sample Australia only Sweden only UK only USA only Australia only, only SNPs in common* Sweden only, only SNPs in common* UK only, only SNPs in common* USA only, only SNPs in common* Total sample except Australia Total sample except Sweden Total sample except UK Total sample except USA Total sample, no cut-off** Total sample, only SNPs in common* Total sample, only SNPs in common adjusted** Total sample, no PC adjustment*** Total sample, X chromosome Men only Women only Total sample, GxSex interaction Extraversion N SNPs N Individuals h2(SNP) (s.e.) p N Individuals h2(SNP) (s.e.) p 849,801 531,616 621,444 530,819 508,337 162,056 162,056 162,056 162,056 845,345 545,625 847,879 849,022 849,801 162,056 162,056 849,801 21,187 849,801 849,801 N SNPs 849,801 11961 2977 3268 2452 3264 2928 3163 2438 3241 8984 8693 9509 8697 17870 11770 11770 11961 11961 5016 6945 N Individuals 11961 .056 .052 .021 .000 .153 .000 .057 .000 .178 .058 .072 .041 .057 .400 .047 .067 .062 .000 .161 .057 h2(SNP) .016 .029 .111 .107 .145 .109 .110 .102 .137 .102 .039 .040 .036 .040 .019 .028 .040 .028 .005 .070 .050 (s.e.) .041 .027 .319 .319 .499 .080 .500 .291 .500 .040 .067 .034 .131 .076 .000 .045 .046 .013 .500 .011 .127 11786 2825 3235 2465 3261 2783 3131 2451 3239 8961 8551 9321 8525 17557 11604 11604 11786 11786 4929 6857 N Individuals 11786 .120 .233 .270 .112 .000 .181 .234 .037 .000 .127 .127 .132 .108 .448 .090 .128 .123 .007 .176 .054 h2(SNP) .125 .030 .120 .111 .146 .108 .120 .104 .136 .099 .040 .041 .038 .041 .018 .028 .040 .029 .006 .071 .051 (s.e.) .042 .000 .026 .008 .229 .500 .068 .013 .394 .500 .001 .001 .000 .004 .000 .001 .001 .000 .099 .006 .140 h2(SNPxSex) (s.e.) p h2(SNPxSex) (s.e.) p .078 .056 .078 .000 .057 .500 Notes: all individuals included in the analyses have a pair-wise genetic similarity < 0.025 except for the ** marked in which no cut-off was made; the first 20 principal components were included as fixed effects in the model, except for the *** marked; N SNPs = number of unique SNPs included in the analyses, all SNPs met criteria for QC within each cohort but were not necessarily genotyped in all cohorts; N individuals = number of individuals included in the analyses; h2 (SNP) = proportion of phenotypic variance explained by all the SNPs; s.e. = standard error; p = p-value; h2 (SNPxSex) = proportion of phenotypic variance explained by genotype-by-sex interaction; PC = principal component; SNPs = single nucleotide polymorphisms; UK = United Kingdom; USA = United States of America; * = analyses based on 162,056 SNPs that were in common between all cohorts (number of ‘unrelated’ individuals differs from analyses based on all the SNPs since genetic relatedness was estimated from the SNPs that were in common between the cohorts only; adjusted = estimate adjusted for imprecise LD between genotyped SNPs and causal variants for causal variants within the allelic frequency spectrum as genotyped SNPs, using the regression coefficient equation: from (assuming c=0), where Ajk is the variance of the off-diagonal elements of the genetic similarity matrix, N is the number of SNPs used to calculate Ajk. c depends on the minor allele frequency of the causal variants See 27 for details. Note that the estimates for the age-cohort separate analyses for Extraversion are based on a bivariate model in which the genetic correlation (rG) between the young and old cohort was estimated at .23 (s.e.=.26, p=.003). Analyses were based on the residuals derived from regression of the (transformed) Neuroticism and Extraversion sum scores on sex, age, sex*age, age2, and sex*age2; residuals were standardized separately for each sex and combined over all cohorts. Cohort membership was included as a fixed effect in the model. The proportion of phenotypic variance explained by genotype-by-sex interaction was not significant when analysed in the Australian cohort only: Neuroticism: h2(SNPxSex) = .02, s.e. = .21, N = 2977, p = .46. Extraversion: h2(SNPxSex) = .00, s.e. = .24, N = 2825, p = .50. Supplementary Table S3 Proportion of variance explained by autosomal SNPs for Neuroticism and Extraversion based on SNP (h2(SNP)) and Pedigree (h2(PED)) data Analysis Trait h2(SNP-U) (s.e.) 1. SNP analysis: 'Unrelated' individuals Neuroticism Extraversion .052 .233 h2(SNP-ALL) .111 .120 (s.e.) 2. SNP analysis: All individuals Neuroticism Extraversion .419 .418 h2(PED-ALL) .023 .023 (s.e.) 3. Pedigree analysis: All individuals Neuroticism Extraversion .457 .449 h2(SNP-ALL) .022 .023 (s.e.) + h2(PED) (s.e.) .143 .138 h2(SNP-R) .062 .067 (s.e.) + + + .312 .310 h2(SNP-U) .066 .070 (s.e.) + h2(PED-ALL) (s.e.) Neuroticism .062 .236 + .129 .049 + .334 .236 Extraversion .063 .288 + .124 .052 + .330 .290 h2(SNP-R) (s.e.) + h2(SNP-U) (s.e.) + h2(PED-ALL) (s.e.) Neuroticism .067 .282 + .127 .048 + .330 .284 Extraversion .011 .353 + .124 .052 + .382 .355 h2(SNP-R) (s.e.) + h2(SNP-U) (s.e.) + h2(PED-ALL) (s.e.) Neuroticism .015 .282 + .129 .048 + .382 .284 Extraversion .113 .347 + .121 .052 + .281 .349 4. Joint analysis: SNP + Pedigree: All individuals 5. Joint analysis: SNP-‘Relateds’ + SNP-‘Unrelateds’ + Pedigree-All (Cut-off 'Relatedness' = 0.025) 6. Joint analysis: SNP-‘Relateds’ + SNP-‘Unrelateds’ + Pedigree-All (Cut-off 'Relatedness' = 0.1) 7. Joint analysis: SNP-‘Relateds’ + SNP-‘Unrelateds’ + Pedigree-All (Cut-off 'Relatedness' = 0.2) Neuroticism Extraversion Notes: Estimates are based on the Australian cohort only; close relatives are included in the analyses; h2(SNP)= proportion of variance explained by autosomal SNPs data (max 529,492 SNPs); s.e. = standard error; h(PED) = proportion of variance explained by pedigree data; h2(SNP-ALL) (s.e.) + h2(PED-ALL) (s.e.) = proportion of variance explained by autosomal SNP data from all individuals + pedigree data from all individuals in a joint analyses; h2(SNP-R) (s.e.) + h2(SNP-U) (s.e.) + h2(PED-ALL) (s.e.) = proportion of variance explained by autosomal SNP data from ‘related’ individuals + autosomal SNP data from ‘unrelated’ individuals + pedigree data from all individuals in a joint analyses; standard errors are shown between brackets; number of individuals included in analysis 1 (‘unrelated’ individuals only) is 2977 for Neuroticism and 2825 for Extraversion; number of individuals included in analyses 2-7 (all individuals) is 5954 for Neuroticism and 5693 for Extraversion. Section 4: Supplementary Figures Supplementary Figure S1 Off-diagonal (a) and Diagonal (b) elements of genetic similarity matrix using all autosomal SNPs and Off-diagonal (c) and Diagonal (d) elements of genetic similarity matrix using autosomal SNPs in common between all cohorts. a b c d Notes: Panels a and c show the distribution of pair-wise genetic similarity between all pairs with a genetic similarity less than 0.025 (off-diagonal elements of the genetic similarity matrix) based on all the SNPs and only the SNPs that are in common between all cohorts, respectively. Panels b and d show the diagonal elements of the genetic similarity matrix (1 + inbreeding coefficient). The figure is based on all individuals with data on Neuroticism and/or Extraversion; N = 12,044 for genetic similarity matrix based on all the SNPs; N =12,039 for genetic similarity matrix based on SNPs that are in common between all cohorts, N SNPs in common between all cohorts = 162,056. Figure S2 Expected pair-wise genetic similarity from autosomal SNP data versus estimated pair-wise genetic similarity from pedigree data Notes: shown is the expected pair-wise genetic similarity from pedigree data (Y-axis) versus the observed pair-wise genetic similarity from autosomal SNP data (X-axis). Note that the values on the Xaxis correspond to the diagonal elements of the genetic similarity matrix (1 + inbreeding coefficient). Polyserial correlation between genetic similarity from pedigree data and genetic relationship from SNP data is .91 (number of observations is 18,304,197). The slope of the regression line is 1.003 (p <.001). 1. Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG. Manual ofthe Eysenck Personality Questionnaire. . Hodder & Stoughton: London., 1975. 2. Eysenck SBG, Eysenck HJ, Barrett P. A Revised Version of the Psychoticism Scale. Personality and Individual Differences 1985; 6(1): 21-29. 3. Costa PM, RR. Professional Manual: Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor-Inventory (NEO-FFI). Psychological Assessment Resources: Odessa FL, 1992. 4. Goldberg LR, Johnson JA, Eber HW, Hogan R, Ashton MC, Cloninger CR et al. The international personality item pool and the future of public-domain personality measures. Journal of Research in Personality 2006; 40: 84-96. 5. Goldberg LR. A broad-bandwidth, public domain, personality inventory measuring the lower-level facets of several Wve-factor models. In: Mervielde I, Deary IJ, De Fruyt F, Ostendorf F (eds). Personality psychology in Europe, vol. 7. Tilburg University Press.: Tilburg, The Netherlands, 1999, pp 7-28. 6. Finkel D, McGue M. Sex differences and nonadditivity in heritability of the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire Scales. J Pers Soc Psychol 1997; 72(4): 929-938. 7. Tellegen A, Waller NG. Exploring personality through test construction: Development of the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire. . In: Boyle GJ, Matthews G, Saklofske DH (eds). The SAGE Handbook of Personality Theory and Assessment: Vol. 2 Personality Measurement and Testing. Sage: London, 2008, pp 261-292. 8. Freeman MF, Tukey JW. Transformations Related to the Angular and the Square Root. Annals of Mathematical Statistics 1950; 21: 607-611. 9. Heath AC, Martin NG. Genetic influences on alcohol consumption patterns and problem drinking: results from the Australian NH&MRC twin panel follow-up survey. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1994; 708: 72-85. 10. Kirk KM, Birley AJ, Statham DJ, Haddon B, Lake RI, Andrews JG et al. Anxiety and depression in twin and sib pairs extremely discordant and concordant for neuroticism: prodromus to a linkage study. Twin Res 2000; 3(4): 299-309. 11. Birley AJ, Gillespie NA, Heath AC, Sullivan PF, Boomsma DI, Martin NG. Heritability and nineteen-year stability of long and short EPQ-R Neuroticism scales. Personality and Individual Differences 2006; 40: 737-747. 12. Saccone SF, Hinrichs AL, Saccone NL, Chase GA, Konvicka K, Madden PA et al. Cholinergic nicotinic receptor genes implicated in a nicotine dependence association study targeting 348 candidate genes with 3713 SNPs. Hum Mol Genet 2007; 16(1): 3649. 13. Medlund P, Cederlof R, Floderus-Myrhed B, Friberg L, Sorensen S. A new Swedish twin registry containing environmental and medical base line data from about 14,000 samesexed pairs born 1926-58. Acta Med Scand Suppl 1976; 600: 1-111. 14. Floderus-Myrhed B, Pedersen N, Rasmuson I. Assessment of heritability for personality, based on a short-form of the Eysenck Personality Inventory: a study of 12,898 twin pairs. Behav Genet 1980; 10(2): 153-162. 15. Rabbitt P, Diggle P, Horan M. The University of Manchester longitudinal study of cognition in normal healthy old age, 1983 through 2003. Aging Neuropsychology and Cognition 2004; 11: 245-279. 16. Deary IJ, Whalley LJ, Starr JM. A Lifetime of Intelligence: Follow-up Studies of the Scottish Mental Surveys of 1932 and 1947. American Psychological Association: Washington D.C., 2009. 17. Deary IJ, Whiteman MC, Starr JM, Whalley LJ, Fox HC. The impact of childhood intelligence on later life: following up the Scottish mental Surveys of 1932 and 1947. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2004; 86(1): 130-147. 18. Deary IJ, Gow AJ, Taylor MD, Corley J, Brett C, Wilson V et al. The Lothian Birth Cohort 1936: a study to examine influences on cognitive ageing from age 11 to age 70 and beyond. BMC Geriatr 2007; 7: 28. 19. Iacono WG, Carlson SR, Taylor J, Elkins IJ, McGue M. Behavioral disinhibition and the development of substance-use disorders: findings from the Minnesota Twin Family Study. Dev Psychopathol 1999; 11(4): 869-900. 20. McGue M, Keyes M, Sharma A, Elkins I, Legrand L, Johnson W et al. The environments of adopted and non-adopted youth: evidence on range restriction from the Sibling Interaction and Behavior Study (SIBS). Behav Genet 2007; 37(3): 449-462. 21. Keyes MA, Malone SM, Elkins IJ, Legrand LN, McGue M, Iacono WG. The enrichment study of the Minnesota twin family study: increasing the yield of twin families at high risk for externalizing psychopathology. Twin Res Hum Genet 2009; 12(5): 489-501. 22. Miller MA, Basu S, Cunningham J, Oetting W, Schork NJ, Iacono WG et al. The Minnesota Center for Twin and Family Research Genome-Wide Association Study. Submitted. 23. Medland SE, Nyholt DR, Painter JN, McEvoy BP, McRae AF, Zhu G et al. Common variants in the trichohyalin gene are associated with straight hair in Europeans. Am J Hum Genet 2009; 85(5): 750-755. 24. Davies G, Tenesa A, Payton A, Yang J, Harris SE, Liewald D et al. Genome-wide association studies establish that human intelligence is highly heritable and polygenic. Molecular Psychiatry 2011. 25. Illumina OmniExpress 700K. http://www.illumina.com/products/human_omni_express.ilmn, 2011, Accessed Date Accessed 2011 Accessed. 26. Yang J, Lee SH, Goddard ME, Visscher PM. GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am J Hum Genet 2011; 88(1): 76-82. 27. Yang J, Benyamin B, McEvoy BP, Gordon S, Henders AK, Nyholt DR et al. Common SNPs explain a large proportion of the heritability for human height. Nat Genet 2010; 42(7): 565-569. 28. Yang J, Manolio TA, Pasquale LR, Boerwinkle E, Caporaso N, Cunningham JM et al. Genome partitioning of genetic variation for complex traits using common SNPs. Nat Genet 2011; 43(6): 519-525. 29. Visscher PM, Yang J, Goddard ME. A commentary on 'common SNPs explain a large proportion of the heritability for human height' by Yang et al. (2010). Twin Res Hum Genet 2010; 13(6): 517-524.