Introduction - The Society for the Study of French History

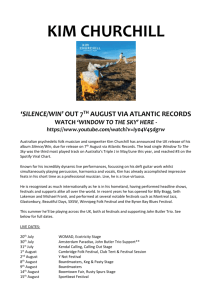

advertisement