1 Principles

advertisement

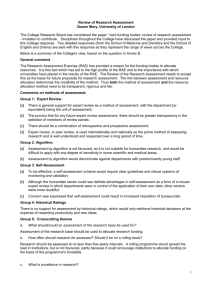

School of English University of Leeds Leeds LS2 9JT Telex 556473 UNILDS G Telephone 0113 343 4752 Fax 0113 343 4774 Response to the Joint Funding Bodies’ Review of Research Assessment November, 2002 This response is the result of extensive consultation and discussion with all academic members of the School through the Board of Studies and the School’s Research Committee. 1 Principles 1.1. The School of English wholly accepts the principle of accountability for publicly-funded research under the dual support system, and has demonstrated its ability to achieve highly within the current system, having gained a 5*A in the 2001 Research Assessment Exercise. Nevertheless, the School wishes to register its anxiety about the seriously detrimental effects of the RAE, and to respond positively to the invitation by Sir Gareth Roberts in the THES (15 November 2002) to ‘leap over the RAE’ and think about new modes of assessment. 1.2. The School is most anxious about: the anti-intellectual effects of a system which prioritises measurable research output in the form of fast, frequent publication, the tendency of which can be to discourage precisely the excellent, responsible research activity it claims to stimulate and measure; the differential split between research and teaching – across the sector, within some departments, and in the career development plans of individual academics – produced by the emphasis on research achievement as the only significant measure of success, an effect exacerbated by the separation of research assessment from teaching quality assessment; the tendency of the present system to institutionalise inequalities between departments, or – in the case of some lower-rated departments working for an improved grade – to produce inequalities within departments. Again, this is most often defined in terms of a split between research and teaching, with a disproportionate burden of teaching falling on pejorativelydescribed ‘teaching only’ colleagues who thus subsidise research-active staff; the disincentives attendant on the present system, where to improve to a 5* is at best to stand still financially, and where, lower down the grading scale, even substantial improvement results in no proportionate reward in funding terms. 1 1.3. The School would therefore ideally wish to see the introduction of a system of assessment which, whilst continuing to emphasise the importance of ‘excellence’ in research, addresses the totality of academic professional responsibility, encouraging a balanced relationship between research and teaching within departments, and thus in individual practice. The gradings and the rewards for high performance arrived at through an equitable and transparent application of this kind of approach would have wider credibility, we feel, than the current divisive system. It is in this spirit that we respond to the specific questions asked in the consultation document, the tendency of many of which, however, is to encourage thinking within rather than beyond current methodologies. 2. Approaches to Assessment 2.1. Expert Review. This is the School’s favoured method (but see also para 2.3), and might include international colleagues. The appropriate judges of research output are professional experts as close as possible to the subject area (or areas, in the case of interdisciplinary activity) and this would also be true of assessments which combined research and teaching. The current move to institutional audit and a generic approach in teaching quality assessment runs the risk of producing criteria insufficiently flexible and sensitive to subject-specific curriculum design and teaching needs. Similar insensivity might also arise from a method of research assessment which did not involve peer scrutiny throughout. It is of course crucial that any peer review system is transparent and fair in its selection of reviewers, in its practices and in its criteria. Assessment should take place at departmental or group level. Public assessment of individuals should be ruled out. 2.2. Algorithm. Algorithmic methods in general (with the possible exception of research student numbers) disadvantage Arts and Humanities subjects. Bibliometric methods based on ‘reputation’ and using citation indices are a crude measurement in areas where the impact of research can be difficult to assess for some years, and where significant publications often appear in collections of essays and are difficult to retrieve by bibliographic methods. Furthermore, the considerations outlined under this head in Annex B work even more unfavourably to struggling departments than do the current arrangements, and are therefore unacceptable in principle. 2.3. Self-assessment. The School is not in favour of self-assessment as a primary method of assessment. The consultation document makes clear that the quality of research must continue to be considered ‘in a global context’ (para 9b), and the School of English endorses assessment against a ‘gold-standard’ of excellence defined appropriately for a particular subject or group of subjects. As the consultation document suggests, any system of self-assessment would therefore have to be based on agreed criteria, externally validated. This would also be necessary in order to avoid the use of self-assessment as a form of strategic ‘games-playing’ potentially worse than those identified as resulting from the current RAE methodology. However, operated in conjunction with expert peer review, and as part of a ‘light touch’ method, self-assessment could be useful. In this system, self-assessment might be combined with a version of external peer review of research of the kind sometimes currently used by institutions for particular purposes. Peer reviewers would estimate the quality of published work through sampling, and might make short visits to departments to assess, for example: its research policy and planning mechanisms; support for individual members of staff; leave arrangements and guidance on applications for research funding; postgraduate research culture. 2.4. Historical ratings. Though this would benefit departments such as our own, it would tend to perpetuate current patterns, inhibiting new developments. It would continue to disadvantage less successful departments, and fail to reward those with an excellent emergent research profile. As a primary method, it is therefore unacceptable. 3. Crosscutting Themes 2 3.1 What could/should an assessment of the research base be used for? The primary aim should be to encourage and enhance responsible research activity throughout the sector, and not simply to solve the problem of how to distribute limited funds by rewarding highachieving departments. This demands a more imaginative relationship between research rating and funding, and one which avoids the disincentives already noted in 1.2, above. An assessment which combined assessment of research and teaching would have the valuable effect of changing the present research-focused culture to one of greater all-round professionalism. Successful departments and interdisciplinary groups will inevitably continue to use the results of national assessment exercises to attract high-quality graduate and postgraduate students. 3.2 How often should research be assessed? The School of English would cautiously support a rolling assessment, in the hope of avoiding the distortions in patterns of appointment to academic jobs and of publication produced by the current system. Alternatively, a cycle of six or seven years would seem most appropriate to research and publication patterns in Arts and Humanities. In any system, some retrospective assessment should be combined with consideration of future plans in order to acknowledge significant continuities within the research activity and culture of a department or group. Encouragement of responsible, longer-term projects, particularly in younger staff, might be achieved by allowing the submission of progress reports rather than simply publication lists. 3.3 What is excellence in research? Intellectual and scholarly rigour and originality, as identified by peers, must continue to be the primary definition of excellence. In Arts and Humanities, this is most obviously measured in terms of individual research achievement in the form of monographs and collections of essays from internationally respected academic publishers, and of articles in refereed journals. Publications of this kind are central to the international standing of individuals, and to international comparability, particularly with peers in North American institutions. Excellence should also be recognised in other kinds of high-level research activity, particularly those which encourage and enable dialogue and development: journal editing, conferences, group projects, etc. However, excellence in Arts and Humanities research might also be manifest in activity and publications which interact with and address a wider public than simply other academics and advanced students. This would include, for example, forms of creative writing and practice, and ‘interdisciplinary’ collaborations with creative practitioners. It would also include publications which address a wider audience, as well as teaching-related output: high-level textbooks which make the best current thinking available to a student audience; and (particularly relevant to an assessment system which combined research and teaching), teaching practice which develops and disseminates research. These kinds of publications should be subject to evaluative assessment, in terms of their intellectual quality and scholarly rigour, in the exactly the same way as those addressed to a peer group. 3.4 Should research assessment determine the proportion of available funding directed towards each subject? Funding levels should ideally be separate from the assessment process which, as pointed out in 3.1 above, should be free to encourage as well as reward excellence on the basis of adequate support across the sector. The terms of any link between the two should be made absolutely clear from the outset of any future exercise. We are concerned that in recent RAE exercises, inconsistency across different UoA’s resulted in marked differences in the funding levels following particular grades. 3.5 Should each institution be assessed in the same way? Yes. This is the only equitable way of proceeding, but should be sensitive to institutional differences which affect the kind and range of activity (see 3.8). We would support the requirement that departments and groups enter 100% of staff. This would be one way of avoiding 3 the ‘games-playing’ developed in response to recent RAE’s. It would also fit more comfortably with assessment of research combined with teaching. 3.6 Should each subject or group of cognate subjects be assessed in the same way? It is crucial that individual subjects or subject-groups should be allowed to develop appropriate methods and criteria for assessment, and that in establishing those methods, creative and interdisciplinary work are properly considered. 3.7 How much discretion should institutions have in putting together their submissions? In the interests of transparency and fairness, there should be clear guidelines. Within these, however, institutions should be given the opportunity to describe their particular profile and ethos. Here, we would favour a version of current practice, as required in RA 5 and 6. 3.8 How can a research assessment process be designed to support equality of treatment for all groups of staff in HE? by separating it from a funding system which perpetuates institutional inequalities; by appropriate recognition of staff career profiles: age, particular circumstances, etc. by appropriate recognition of institutional conditions: leave; teaching loads, etc. 3.9 Priorities: what are the most important features of an assessment process? To encourage, support and evaluate the full range of professional academic activity through a process which is rigorous, fair to individuals and institutions, and transparent in its methods and criteria without being unduly burdensome to either institutions or assessors, and which is supported by adequate funding for the Higher Education sector. 4