UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS

advertisement

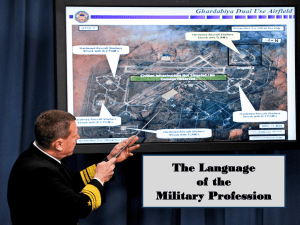

TACTICAL PLANNING I BOL4815 UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS Basic Officer Course The Basic School Marine Corps Combat Development Command Quantico, Virginia 22134-5019 BOL4815 TACTICAL PLANNING I Student Handout "Battle should no longer resemble a bludgeon fight, but should be a test of skill, a maneuver combat, in which is fulfilled the great principle of surprise by striking from an unexpected direction against an unguarded spot." Captain Sir B. L. Hart, 1944 INTRODUCTION. Success in combat depends upon small-unit leaders who can adapt and make sound, timely decisions on a constantly changing, fluid battlefield. To achieve success, leaders must be able to understand the situation, decide and execute decisively against the enemy. The tactical planning instruction you will receive at The Basic School is focused on developing the skills necessary for beginning decision makers to successfully accomplish the mission under a variety of conditions. 1. There are two styles of decision-making analytical and recognitional. a. Analytical. The analytical style of decision-making is characterized by lengthy, detailed collection of information. The goal of analytical decision-making is to determine the best or "optimal" course of action. b. Recognitional. The recognitional style of decision-making implies that a leader can mentally assess the situation at hand and quickly arrive at a decision based upon his experience, his ability to recognize the presence or absence of enemy patterns or indicators, as well as his "gut feeling" or intuition. This style of decision-making seeks a course of action that satisfies the situation vice one that optimizes it. 2. TROOP-LEADING STEPS (BAMCIS). The troop leading steps are a sequence of events which unit leaders use in most tactical operations. These steps do not always occur in a specific order, many times two or more may occur concurrently. The troop-leading steps are simply a tool, which aids leaders in formulating initial plans and time schedules upon receipt of a mission. a. Begin planning. The receipt of a mission triggers the entire BAMCIS cycle; however, tactical planning is anticipatory and continuous. To make effective use of available time, the leader issues a Warning Order to his subordinates. (1) THE ESTIMATE OF THE SITUATION (METT-T). Like the troop-leading steps (BAMCIS), the estimate of the situation (METT-T) is a tool, which aids a commander as he plans tactical operations. This tool is especially helpful to a decision maker as a frame of reference, which serves to remind him of various factors normally considered during tactical planning. During this class you will be exposed to a modified version of the factors normally considered in the estimate of the situation. Once the basics are mastered on the squad level, you will be introduced to several additional factors during subsequent tactical planning classes, which will aid in tactical planning on the platoon level and above. (a) Mission analysis. The first step in the estimate is mission analysis; it begins upon receipt of the mission. It is the means for the unit leader to gain an understanding of the mission. 1. Task analysis. The unit leader must identify and understand all that is required for the successful accomplishment of the mission. This includes tasks received in the unit's task statement and coordinating instructions from the higher commander's operations order. 2. Limitations. These are restrictions on the freedom of action of the friendly force; these prohibit the commander from doing something specific. Tactical control measures, rules of engagement (ROE), and the statements, "Be prepared to...", "Not earlier than...", "On order...", are some examples of limitations. (b) Enemy forces. The objective of an analysis of the enemy situation is to deduce the enemy's most probable course of action. Its development comes from sources including enemy doctrine and historical data, as well as current enemy activities as 3 BOL4815 TACTICAL PLANNING indicated in the higher commander's operation order. Ideally, the information used to analyze the enemy situation includes the following: 1. Composition, disposition, strength. Describe your enemy. It is an identification of the forces and equipment that the enemy can bring to bear within your unit's zone or sector. Also considered are known and suspected enemy locations and strength estimates in relation to personnel, equipment and support capabilities. The elements of the acronym SALUTE are helpful when developing and organizing this information. 2. Capabilities and limitations. What can the enemy do to me? What can he not do to me? In this subparagraph, the information listed under Composition, Disposition, Strength, is analyzed in relation to the enemy's ability to conduct operations against our unit. The enemy force is analyzed concerning its ability or inability to conduct various operations against our unit under any reasonably foreseeable situation. Is the enemy force capable of defending, reinforcing, attacking, withdrawing, or delaying? The acronym DRAW-D serves as a reminder of the minimum factors to be considered. For example, can the enemy effectively attack at night? Can he conduct a deliberate defense against us or does he lack sufficient forces and equipment? Will the enemy be reinforced by elements of other units as a result of our attack? How long will this reinforcement take? Can it be done at night, is it a vehicular transported reinforcement force or will it be traveling on foot? 3. Enemy most probable course of action. What will the enemy try to do to me? Based on the analysis of the enemy's capabilities and limitations, deduce the enemy's most probable course of action in relation to our action. For example, "the MPCOA is to withdraw to the northwest as a result of our attack and attempt to join other enemy forces west of objective Alpha." (c). Terrain/weather analysis (OCOKA-W). REMEMBER, THE FACTORS WHICH MAKE UP OCOKA-W MUST ALWAYS BE CONSIDERED FROM BOTH THE FRIENDLY AND ENEMY PERSPECTIVES. The unit leader conducts analysis of the five military aspects of terrain relevant to his mission. Certain situations may elevate one element of OCOKA-W to a level of importance above that of one or more of the remaining elements (extreme weather, for example). Having received the higher commander's analysis, a unit leader can more easily analyze his sector or zone with respect to friendly and enemy capabilities. For example, in offensive operations, the unit leader analyzes terrain/weather from the objective area working back to the assembly area. A logical sequence for rapidly analyzing terrain and weather is as follows: 1. Observation and fields of fire. What can and cannot be seen from where? What can and cannot be hit by fire? Observation is the influence of terrain on reconnaissance and target acquisition. Fields of fire are the influence of terrain on the effectiveness of weapons systems. 2. Cover and concealment. Where can I not be hit by fires? Where can I not been seen? Cover is protection from effects of firepower. Concealment is protection from observation or target acquisition. The analysis of cover and concealment is often inseparable from the consideration of observation and fields of fire. Weapons systems must have both cover and concealment to be most effective and to increase survivability. 3. Obstacles. Obstacles are any natural or man-made obstructions that canalize, delay, restrict, or divert the maneuver or movement of a force. Obstacles will be taught in detail during subsequent engineering classes. 4. Key terrain. Key terrain is any area whose seizure, retention, or control affords a marked advantage to either combatant. Using his map and information already generated, the unit leader must identify terrain that could be used as positions for weapons or for units to dominate friendly or enemy approaches into or within the objective area. Remember, key terrain need not be occupied to be controlled. Direct or indirect fire can be used to control access to key terrain. 5. Avenues of approach. Avenues of approach are movement routes to an objective. A viable avenue of approach usually offers mobility corridors. These are areas within the avenue of approach that permit movement and maneuver. They permit friendly and enemy forces to advance or withdraw, and to capitalize on the principles of mass momentum, shock and speed. When friendly forces are attacking, friendly avenues of approach to the objective must be identified, and enemy avenues of approach that could affect friendly movement--for example, counterattack avenues--must be identified. 6. Weather. Weather is analyzed using the five military aspects of weather: temperature and humidity, precipitation, wind, clouds, and visibility (both day and night). To determine its cumulative effect on the operation, weather must be considered in conjunction with the terrain associated with the unit's mission. Weather affects equipment (including electronic and optical), terrain (trafficability), and visibility, but its greatest effect is on the individual Marine. During inclement weather or in extreme heat or cold, the amount of time spent on leadership and supervision must increase as the severity of the weather increases. 2 TACTICAL PLANNING I BOL4815 Inclement weather affects visibility and movement, unit efficiency and morale, and makes command and control more difficult. Poor weather conditions can be as much of an advantage to a unit as it is a disadvantage, depending upon unit capabilities, equipment and level of training. (d) Troops and support available. Any course of action the unit leader considers must take into account the number of Marines and support assets available for the operation. The mental and physical condition of the Marines, their level of training, the status of their equipment, fire support assets, and logistics must be considered. (e) Time. The ability to appreciate the aspects and effects of time and space is one of the most important qualities in a leader. Time is vital to all operations; it drives planning and execution. The unit leader gets his indication of time available from his commander. The amount of time a unit has to prepare for or to execute an operation determines the detail possible during the planning process. Initial estimates of time should be used to identify any critical timings in the operation. Critical times can include planning time, LD time, movement time, defend-no-later-than time, time available to prepare and rehearse the attack or defense, time available for reconnaissance, transportation means (helo, vehicular, foot-mobile etc.). Both opposed and unopposed rates of movement should be considered. b. Arrange for reconnaissance. Initially, the unit leader asks, "What information am I lacking?" If possible, the unit leader arranges for a physical reconnaissance of his objective, route, or defensive position. He considers the route, security, subordinates to accompany him, and the time available for reconnaissance. If a physical reconnaissance is impossible, the commander should at least use a map, aerial photo, or visual reconnaissance from a vantage point in order to conduct his leader's reconnaissance. c. Make reconnaissance. The commander now acts to answer his questions, through a reconnaissance. His recon will either confirm his plan or cause him to make adjustments to it. On a physical reconnaissance selected subordinate leaders normally accompany him. The personnel accompanying the leader will vary according to the tactical situation. The leader should take as many subordinate leaders as the situation requires, while other subordinate leaders supervise the preparations necessary for the upcoming mission. d. Complete the plan. After updating his estimate of the situation (METT-T) with information gained during his reconnaissance, the leader makes his decision as to how he will accomplish the mission and completes his operation order. e. Issue the order. The leader issues his order orally to his subordinate leaders. Combat Orders I introduces operation orders and order-issuing techniques. f. Supervise. The leader ensures that his plan is adhered to by listening to his subordinate leaders as they issue orders, by inspecting Marines and their equipment, and by observing them as they conduct rehearsals. He also ensures adherence to any established time line. If any changes to the original plan are required, due to recent changes in the situation, the commander must adjust his plan accordingly. 3