Transport of the Mechanically Ventilated Patient

advertisement

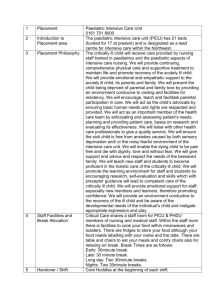

Transport of the Mechanically Ventilated Patient Cardiopulmonary Department MANUAL SECTION POLICY CODE and NUMBER PURPOSE: The purpose of this policy is to provide transportation of mechanically ventilated patients for diagnostic or therapeutic procedures. DESCRIPTION/DEFINITION: Transportation of mechanically ventilated patients for diagnostic or therapeutic procedures is always associated with a degree of risk. Every attempt should be made to assure that monitoring, ventilation, oxygenation, and patient care remain constant during movement. Patient transport includes preparation, movement to and from, and time spent at destination. CONTRAINDICATIONS: Transportation of the mechanically ventilated patient should not be undertaken until a complete analysis of potential risks and benefits has been accomplished. Contraindications include: 1. Inability to provide adequate oxygenation and ventilation during transport either by manual ventilation or portable ventilator, (2,17-19) 2. Inability to maintain acceptable hemodynamic performance during transport, (20-22) 3. Inability to adequately monitor patient cardiopulmonary status during transport, (2l) 4. Inability to maintain airway control during transport, 5. Transport should not be undertaken unless all the necessary members are present. HAZARDS & COMPLICATIONS: Hazards and complications of transport include the following: 1. Hyperventilation during manual ventilation may cause respiratory alkalosis, cardiac dysrhythmias, and hypotension. (2,17,18) 2. Loss of PEEP/CPAP may result in hypoxemia. (23) 3. Position changes may result in hypotension, hypercarbia, and hypoxemia. (21) 4. Tachycardia and other dysrhythmias have been associated with transport. (20-22) 5. Equipment failure can result in inaccurate data or loss of monitoring capabilities. (15-16) 6. Inadvertent disconnection of intravenous pharmacological agents may result in hemodynamic instability. (15,16,20) 7. Movement may cause disconnection from ventilatory support and respiratory compromise. (23,24) 8. Movement may result in accidental extubations, (23) 9. Movement may result in accidental removal of vascular access. (4-6,15,16) 10. Loss of oxygen supply may lead to hypoxemia. Transport of the Mechanically Ventilated Patient Cardiopulmonary Department LIMITATIONS OF METHOD: The literature suggests that nearly two thirds of all transports for diagnostic studies fail to yield results that affect patient care. (15,16) ASSESSMENT OF NEED: The attending physician should assess the necessity for transport. The risks of transport should be weighed against the potential benefits from the diagnostic or therapeutic procedure to be performed. ASSESSMENT OF OUTCOME: The safe arrival of the mechanically ventilated patient at his/ her destination is the indicator of a favorable outcome. This outcome can be ensured by the use of a CO2 Detector to address accidental and/or decannulations. RESOURCES: Equipment: 1. Emergency airway management supplies should be available (e.g., laryngoscope, endotracheal tubes, stylet, portable suction unit, “Go” Bag supplies). 2. Portable oxygen source of adequate volume 3. A self-inflating bag and mask of appropriate size 4. Transport ventilators have been shown to provide more constant ventilation than manual ventilation in some instances. If a transport ventilator is used, it should (2,l7-l9) have independent control of tidal volume and respiratory frequency; (23) 5. Be able to provide continuous mechanical ventilation as in assist-control or intermittent mechanical ventilation (not necessarily both); 6. Deliver a constant volume in the face of changing pulmonary impedance. 7. Monitor airway pressure. 8. Provide a disconnect alarm; 9. Be capable of providing PEEP. 10. Provide an FIO2 of 1.0. 11. A pulse oximeter may be desirable. 12. Appropriate pharmacological agents (ACLS) should be readily available. 13. Portable monitor should display EKG and heart rate and provide at least one channel for vascular pressure measurement. 14. An appropriate condenser humidifier should be used to provide humidification during transport. 15. Stethoscope Personnel: A nurse and a respiratory therapist should accompany all mechanically ventilated patients during transport. At least one team member should be proficient in operating and troubleshooting all of the equipment. Transport of the Mechanically Ventilated Patient Cardiopulmonary Department MONITORING: Monitoring provided during transport should be similar to that during stationary care. Electrocardiograph should be continuously monitored for signs of dysrhythmias. Heart rate should be monitored continuously. Blood pressure should be monitored continuously if invasive lines are present. In the absence of invasive monitoring, blood pressure should be measured intermittently via sphygmomanometer. Respiratory rate should be monitored intermittently. Continuous pulse oximetry may be useful for patients with borderline respiratory function. Breath sounds should be monitored intermittently. INFECTION CONTROL: Standard Precautions should be observed. (25) All equipment should be disinfected between patients. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations for control of exposure to tuberculosis and droplet nuclei are to be implemented when patient is known or suspected to be immunosuppressed, is known to have tuberculosis, or has other risk factors for the disease. (26) NOTE: IN THE EVENT OF A DECANNULATION, REFER TO THE POLICY “TRACH TUBE REINSERTION” POLICY (TX – 246) Transport of the Mechanically Ventilated Patient Cardiopulmonary Department REFERENCES: 1. Olson CM, Jastremski MS, Vilogi JP, Madden CM, Beney KM. Stabilization of patients prior to interhospital transport. Am J Emerg Med 1987;5:33-39. 2. Braman SS, Dunn SM, Amico CA, Millman RP. Complications of intra-hospital transport in critically ill patients. Ann Intern Med 1987;107:469-473. 3. Edlin S. Physiological changes during transport of the critically ill. Intensive Care World 1989;6:131. 4. Smith I, Fleming S, Cernaianu A. Mishaps during transport from the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 1990;18:278-281. 5. Insel J, Weissman C, Kemper M, Askanazi J, Hyman AI. Cardiovascular changes during transport of critically ill and postoperative patients. Crit Care Med 1986;14:539-542. 6. Ehrenwerth J, Sorbo S, Hackel A. Transport of critically ill adults. Crit Care Med 1986;14:543-547. 7. Andrews PJ, Piper IR, Dearden NM, Miller JD. Secondary insults during intra-hospital transport of headinjured patients. Lancet 1990;335:327-330. 8. Gentleman D, Jennett B. Audit of transfer of unconscious head-injured patients to a neurosurgical unit. Lancet 1990;335:330-334. 9. Kanter RK, Tompkins JM. Adverse events during inter-hospital transport: physiologic deterioration associated with pre-transport severity of illness. Pediatrics 1989;84:43-48. 10. Katz VL, Hansen AR. Complications in the emergency transport of pregnant women. South Med J 1990;83:7-10. 11. Martin GD, Cogbill TH, Landercasper J, Strutt PJ. Prospective analysis of rural inter-hospital transfer of injured patients to a referral trauma center. J Trauma 1990; 30: 1019-1020. 12. Valenzuela TD, Criss EA, Copass MK, Luna GK, Rice CL. Critical care air transportation of the severely injured: does long distance transport adversely affect survival? Ann Emerg Med 1990;19:169-172. 13. Harrahill M, Bartkus E. Preparing the trauma patient for transfer. J Emerg Nurs 1990;16:25-28. Transport of the Mechanically Ventilated Patient Cardiopulmonary Department 14. LaPlante G, Gaffney TM. Helicopter transport of the patient receiving thrombolytic therapy. J Emerg Nurs 1989;15(2, Part 2):196-200. 15. Indeck M, Peterson S, Smith J, Brotman S. Risk, cost, and benefit of transporting ICU patients for special studies. J Trauma 1988;28:1020-1025. 16. Hurst JM, Davis K Jr, Johnson DJ, Branson RD, Campbell RS, Branson PS. Cost and complications during in-hospital transport of critically ill patients: a prospective cohort study. J Trauma 1992;33:582-585. 17. Hurst JM, Davis K Jr, Branson RD, Johannigman JA. Comparison of blood gases during transport using two methods of ventilatory support. J Trauma 1989;29: 1637-1640. 18. Gervais HW, Eberle B, Konietzke D, Hennes HJ, Dick W. Comparison of blood gases of ventilated patients during transport. Crit Care Med 1987;15:761-763. 19. Weg JG, Haas CF. Safe intra-hospital transport of critically ill ventilator-dependent patients. Chest 1989;96: 631-635. 20. Taylor JO, Chulay JD, Landers CF, Hood WB Jr, Abelman WH. Monitoring high-risk cardiac patients during transportation in hospital. Lancet 1970;2:1205-1208. 21. Waddell G. Movement of critically ill patients within hospital. Br Med J 1975;2:417-419. 22. Rutherford WF, Fisher CJ. Risks associated with in-house transportation of the critically ill (abstract). Clin Research 1986;34:414. 23. Branson RD. Intra-hospital transport of critically ill, mechanically ventilated patients. Respir Care 1992;37 (7):775-795. 24. Johannigman JA, Branson RD, Campbell R, Hurst JM. Laboratory and clinical evaluation of the MAX transport ventilator. Respir Care 1990;35(10):952-959. 25. Centers for Disease Control. Update: Universal Precautions for prevention of transmission of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus, and other blood-borne pathogens in health-care settings. MMWR 1988;37:377-382,387-388. 26. Centers for Disease Control. Guidelines for preventing the transmission of tuberculosis in health care settings, with special focus on HlV-related issues. MMWR 1990: 39:1-29.