Black death

advertisement

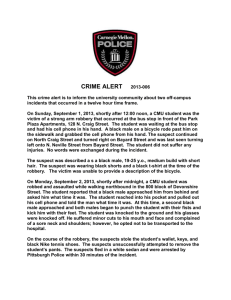

Black death Homicides plague minority areas By Mark Houser TRIBUNE-REVIEW Sunday, July 18, 2004 A wave of street killings is sweeping through Pittsburgh's black neighborhoods, leaving a trail of grieving families, overworked police and bewildered community leaders. The onslaught pushed the murder rate in Pittsburgh last year to ninth-highest among cities in the biggest U.S. metropolitan areas, higher than in Miami and Los Angeles and triple New York's rate. One-fourth of Pittsburgh's population is black, but 22 of the city's 25 homicide victims this year have been black. Ten men have been charged in 11 of the black killings. All are black, though charges in one case were dropped. Sometimes the victims are innocents. Penn Hills student Karis Adams, 14, died May 31 when gunmen peppered the car she was riding in at a stop sign in the city's LincolnLemington neighborhood. A stray bullet felled Gwendolyn Jones, 47, a mother of five, in the city's Fairywood section that same month. Often the victims aren't innocents. Clayton Wright, 19, was carrying about 30 packets of crack cocaine when someone shot him off his bike late May 17 in Hazelwood. Wright had three outstanding arrest warrants for drugs and burglary, court records show. He also had a baby daughter, Nevaeh, or "Heaven" spelled backward, Terri Wright said as she caressed her son's body at the funeral home. A snapshot of the baby bouncing on her father's knee, with grandmother beaming alongside, leaned on Wright's coffin lid, next to a red "World's Best Dad" ribbon. Tim Stevens, head of the Pittsburgh branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, said he has grown increasingly pessimistic about halting black-on-black violence. "Somehow we need to stop this, because we're going to spin ourselves into an eternity of devastation that will be so deep we will never climb out of it," he said. Adrienne Young founded Tree of Hope, a group that helps families who have lost loved ones to murder. Her son, Javon, was a freshman at Carnegie Mellon University when he died in 1994 during a robbery. He had no police record and was an excellent student, she said. "There's lots of mothers out there who think as long as their son is helping them pay the light bill or make a car payment, or buy a house -- and I know people like this -- that whatever he's doing is all right, until he gets killed," she said. "I say to them, 'Don't you realize you were a part of your son's demise?'" Worse than expected Murder in Pittsburgh and other American cities peaked during the crack-fueled gang wars of the early 1990s. By the mid-1990s, the killings had begun a steady decline as death and prison wore down the crack trade. But the body count is creeping back up. The increase here is due almost entirely to murders of blacks, which have doubled in Allegheny County since 2000. Turf battles over cheap heroin spur many killings, police and experts say. Alfred Blumstein, a nationally recognized crime expert and professor at Carnegie Mellon University, is part of a research team trying to determine which "root causes" are consistent with high murder rates. Looking at 67 U.S. cities of 250,000 or more people, the research team used statistics such as poverty, male unemployment, single motherhood and race to predict expected murder rates for each city. They concluded Pittsburgh's 2002 murder rate of 14 per 100,000 people was significantly higher than it should have been. Last year's rate shot up to 21 per 100,000. Statistics can't describe the pain of Clifford Wilson, 45, a Homewood resident for 35 years. His son, Preston Wilson, 19, was gunned down in North Braddock in September. "When I was coming up as a kid, it was nowhere like the way it is now," he said. "There was unity in the community. There were fights, but we settled them with our fists. But then crack got in, and it just went crazy." Wilson said his son was a drug dealer and gang member who lived on his own. The teen had a metal rod in his hip from a previous shooting and was on crutches when he was killed. "You have these young kids out here. ... I don't know, they're just savages, man," Wilson said. Stopping the violence Pittsburgh City Councilman Sala Udin said the rise in black murders cries out for a unified plan of action. "There's enough insufficiency to go around across the board," Udin said. "There's a lot more that could be done by communities, by the education system, by the job system, by families, by churches, by individuals who should be responsible for their own behavior. And there is a hell of a lot more that could be done with a coordinated attack by law enforcement." Last month, the U.S. Department of Justice announced it would send violent crime impact teams from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives to 15 cities, including Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh's team, which includes 14 federal agents, five city police detectives and a county sheriff's deputy, will spend the rest of the year in Homewood, the North Side and the Hill District. They have identified about 60 violent repeat offenders who will be monitored closely, said Mary Beth Buchanan, U.S. attorney for the Western District of Pennsylvania. It's the latest in a series of federal anti-crime efforts. Buchanan's office this year has distributed about $758,000 in federal money to fight gun crime. She also has stepped up firearms prosecutions, combing through police arrest records to find people eligible for stiffer federal sentences. In the first 10 months of the 2004 fiscal year, her office -- armed with a new prosecutor dedicated solely to gun crimes -- brought indictments on federal gun charges against 94 people, already more than double last year's total. Pennsylvania sentencing guidelines for illegal gun possession range from probation to a prison sentence of at least three years for people with a history of violent crime. In contrast, the federal minimum sentence for having a gun while selling drugs is five years on top of the drug charge, and those with a history of drug arrests get 15 years without parole, even if they never drew the weapon. Defense attorney Ralph Karsh said a young man caught with a gun and crack cocaine for the second time came to him shellshocked. He had been told the three-year state sentence he expected is now potentially 15 years in federal prison. "I guess it all depends on your viewpoint, but to me, that's absurd to do to a 19-year-old kid," Karsh said. "... The belief is it will give us some piece of mind, because that person is gone. But someone can take his place on the corner in five minutes." The tactics signal a big strategy change. In recent years, Pennsylvania's Western District consistently has had among the smallest caseloads of federal weapons charges in the nation. In fiscal 2003, 38 new defendants faced weapons charges in the district. Alaska, with one-sixth the population, had 34. Buchanan said that until recently, her office spent more time on narcotics investigations and pursuing illegal gun sales. The victims A record 125 people were killed in Allegheny County last year. The fact is that most people in the region have little to fear. Only one in eight residents of Allegheny County is black. But three in four of the county's murder victims last year were black, and the imbalance is growing. Whites kill whites too, but the number of white murders has changed little since 1990, hovering at about 30 a year. Fewer than 10 percent of homicides last year involved whites killing blacks, or vice versa. And while murders of innocent bystanders draw more attention, most black victims here and across the nation are men in their late teens or early 20s, usually involved in selling drugs, shot by other young black men in neighborhoods like Homewood, the Hill District and the North Side. About 70 percent of Pittsburgh murder victims last year had criminal records, according to police statistics. Those victims averaged more than five arrests, mostly for drugs. "A lot of the killing now is because dealers can't ask for police protection," said Pittsburgh police Deputy Chief William Mullen. "They're carrying a lot of valuable heroin, so they're easy robbery targets." Jason Perminter, 24, of Crafton, knows about the dangers. Someone fatally shot his brother, Justin Perminter, 18, on Federal Street on the North Side two years ago. Police said the slaying stemmed from a drug-dealing turf dispute. Jason Perminter was at the Allegheny County Courthouse in May facing charges as a heroin dealer. He said the drugs were just for him. "You gotta get the guns off the streets for (the violence) to be stopped," Perminter said as he headed for the courtroom. Sure, he admitted, he had carried his own unlicensed 9 mm pistol. But he said it was stolen recently, and he doesn't want to risk carrying another one because getting caught now could mean federal time. So he takes other precautions. "I don't really go out into the street now, so many people getting killed," Perminter said. Arms race Each year, city police seize more guns than the last. In 2003 Pittsburgh cops made 472 arrests for gun violations, up 75 percent from just three years earlier. Detective Jason Snyder, 33, leads the city's "impact squad," a four-member plainclothes team that focuses on firearms and drug arrests in the city's most dangerous neighborhoods. Snyder's team got off to a productive start in 2004. Arriving in Homewood just before midnight on New Year's Eve, he and Detective Ed Fallert, 37, chased down and caught one man with an illegal gun. They were waiting for the transport to take him in for booking when the clock struck midnight. "It just erupted. It was like Iraq," Snyder said of the roar of celebratory gunfire. Before the shift was up, Snyder and Fallert had two more arrests. Fallert, Snyder and Detective Mark Goob said they get little help in the neighborhoods they patrol. "We're always wrong. We're always 'harassing' their son. We're not always out there, policing that neighborhood to make it better. We're harassing them," Snyder said. Detective Dennis Logan, 43, who is black, is the city's senior homicide investigator. He grew up in the St. Clair Village projects. He admired the local gang when he was a boy. "I thought they were the cool guys. They had a fancy car and all," Logan said. Then one of them helped firebomb the house of Logan's childhood sweetheart, killing her and her older brother in retaliation for a fight. Logan became a cop. "I've been on the job long enough now that a lot of people who didn't hear nothing, see nothing, know nothing -- now I'm standing over their son's body, and they're (asking), 'Why won't somebody come forward?'" he said. "And you almost want to say, 'Well, remember I interviewed you last year? Now you want everybody to come forth, but when I talked to you last summer, you said, "I ain't no snitch. I ain't got nothing to do with that."'" Sometimes witnesses are scared, Logan said. Many times, they want vengeance and prefer to take care of the matter themselves. Homewood In an infamous case from 2002, masked men sprayed a Homewood sandwich shop with gunfire, killing 8-year-old Taylor Coles, her father and another man and wounding her mother. After neighbors and authorities responded with indignation, the shootings subsided. Only one more person was killed in Homewood that year. "After Taylor Coles got killed, there was a community meeting, and 500 people came," said Valerie Dixon, of East Liberty, a victims advocate for the county juvenile courts. Her son was murdered in 2001. "But by the 11th and 12th meeting, it was 20. After that, it was just the people who organized the meeting," she said. "People are not committed." Last year, Homewood again was the most violent neighborhood, with 11 slayings. Seven other Homewood residents were killed nearby. Men argued loudly at a Homewood barbershop recently about who's to blame. One customer blamed the violence on a lack of jobs, saying murders declined during the economic boom years under Bill Clinton but are rising under George W. Bush. That set off Pete Glover, 46. He served time in prison for simple assault. Now, he said, he tries to talk sense to the young men who come to take their turn in his barber chair. "It's not a political thing, man. It's a community thing. How can we direct anything to the politicians when we can't straighten out our own community right here?" Glover said. Even where employment opportunities exist, the wages can't compete with the hundreds, or thousands, of dollars to be made on a good weekend selling heroin. Philadelphia native Ron "Karim" Watson Jr., 43, said he moved to Pittsburgh to turn his life around after four years in prison for armed robbery. Watson said he makes a decent living now as a crane operator. He goes to bars in Homewood and elsewhere to recruit workers for the union, with varying success. "Some guys will pull out $2,000," he said. "They say, 'This is my job.' I say to them, 'But you might not live to be 30.'" Detective Logan, trying to coax statements or confessions out of recalcitrant witnesses or suspected killers day after day, sometimes wonders what he is accomplishing. "There are so many people that I've interviewed in the past that are either dead now or in jail," he said. "You saw it coming, but there's nothing you can do about it, because there's nothing the family can do about it. ... Once they get to a certain stage of life, they're not going to listen to anybody."