doc - Dr. N. Seth Nelson

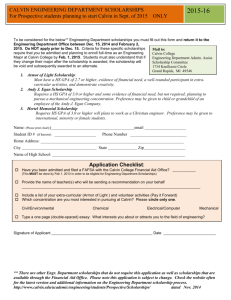

advertisement

JOHN CALVIN’S THEOLOGY OF MUSIC: AN INTRODUCTION PART ONE by N. Seth Nelson for In Covenant (newsletter of Covenant OPC) As a servant of Christ and a pastor of churches in Strasbourg and Geneva, John Calvin had a high view of music, both in the public worship of the church and in the recreation of the home. He provided for the singing of the psalms of David as well as other hymns for use in public worship, and he encouraged the use and development of the divine gifts of music in every sphere of life. This short two-part series will present an overview of Calvin’s views of music based on his own words. But first, I will briefly summarize some foundational material that will put Calvin’s views on music in context.1 According to Calvin, the public worship of God consists of “the preaching of his Word, the public and solemn prayers, and the administration of his sacraments,” and the prayers are of “two kinds: the ones made with the word only, the others with song.” The Word is central to worship, but it is only a means to the end “that the divine name may be celebrated by us on the earth.” So he says, “May we be so enthusiastic to sing his praises that it becomes our main pursuit,” for this is “something which is more necessary than one can say.”2 The goal of public worship is not publicity, but worship: “When we pray to God here in the church, and sing the psalms, it is not to show ourselves off, as hypocrites do, but to declare that we seek nothing but that God may be glorified among us.” These praises are not mere outward ceremonies, but sincere worship from the heart. “Spiritual songs cannot be well sung save with the heart,” for “God wishes first of all for inward worship, and afterwards for outward profession.” The true worship of God “ought to proceed from the deepest feeling of the heart, and therefore we need the direction and influence of the Spirit, that we may sing those praises in a proper manner.”3 This spiritual worship is to be governed by God’s Word, for “obedience is the foundation of true worship,” and is its “first and leading principle.” Calvin believed that in worship, God “rejects what he does not command,” and therefore “the rule for worshipping Him must not be sought from any other source than from His own word, and that we ought to abide by the only and pure worship which is there enjoined.” As a result Calvin says, “Let us be aware, then, that we are – with good reason – greatly exhorted to take thought of ourselves day and night (Matt. 26:41; Col. 4:2), and to be vigilant (I Pet. 5:8) to know how God wants to be worshipped and served.”4 Calvin had a real appreciation for music, which is evident in his promotion of music (through preaching, printing, and education) and his above average contribution to congregational singing. His first rate education, which included some study of music, is displayed in his knowledge of the history and philosophy of music. Having said that, take note that Calvin’s comments on music are not that of a music theoretician or aesthetician, but a theologian and a pastor. According to Calvin, God’s being and his creation are the measure of beauty, which “is a gift of God which we should esteem.” Art, the development of God’s beautiful creation, is a privilege and ability given by God. As such, artists should cultivate in conformity with the character of God. Calvin tries to avoid a slippery slope: legalistic binding of consciences to use only what is necessary on the one hand, and licentious indulgence on the other. As a middle way, “the use of God’s gifts is not wrongly directed when it is referred to that end to which the Author himself created and destined them for us, since he created them for our good, not for our ruin.” This includes receiving pleasure from God’s creation (e.g., food, clothing, flowers, music, etc.) even “apart from their necessary use,” provided that we always “recognize the Author and give thanks for his kindness toward us.”5 Music in General. Calvin has much to say about music, which he gives singular praise: “Now among the other things proper to recreate man and give him pleasure, music is either the first or one of the principal, and we must think that it is a gift of God deputed to that purpose.” Thus, Calvin not only allowed, but encouraged the study and practice of making music to the glory of God. We are to continually study and enjoy God’s creation in order to know better his worthiness of praise, “the Divine goodness which can never be sufficiently proclaimed.”6 Music can be used for expressing our joy or comforting others. Calvin says simply, “Singing is an indication of joy.” And elsewhere: “Although it appears to be unreasonable and inappropriate to prescribe a song of joy in the midst of grief, yet we have elsewhere seen that this form of expression is well fitted to arouse those who groan under the burden of sorrow, fear, and cares.” Conversely, plaintive tunes or the lack of music can express sorrow and lamentation. Calvin says, “For when the Prophets announce the vengeance of God, they are wont to say, ‘cease shall all joy among you; ye shall not play any more with the harp or with musical instruments [cf. Isa. 24:8-9].’” In his commentary on Luke 8:52, Calvin mentions the “plaintive airs” of the flute at a funeral, but he warns against the abuse of wallowing in grief rather than allaying it. The use of music he commends, but the abuse he condemns: “It is true that the Flute and the Taber, and such other like things are not to be condemned simply of their own nature: but only in respect of men’s abusing of them.”7 Music has great power to influence, and this can be used for good or evil. Calvin says: “In fine, we all know by experience what power music has in exciting men’s feelings, so that Plato affirms, and not without good reason, that music has very much effect in influencing, in one way or another, the manners of a state.” Again: For there is scarcely anything in the world which is more capable of turning or moving this way and that the morals of men, as Plato prudently considered it. And in fact we experience that it has a secret and almost incredible power to arouse hearts in one way or another. Wherefore we ought to be the more diligent in regulating it in such a way that it be useful to us and not at all pernicious. Wherefore that much more ought we to take care not to abuse it, for fear of fouling and contaminating it, converting it to our condemnation, when it was dedicated to our profit and welfare. If there were no other consideration than this alone, it ought indeed to move us to moderate the use of music, to make it serve everything virtuous, and that it ought not to give occasion for our giving free rein to licentiousness, or for our making ourselves effeminate in disordered delights, and that it ought not to become an instruments of dissipation or of any obscenity…It is true that every evil word (as Saint Paul says) perverts good morals, but when the melody is with it, it pierces the heart that much more strongly and enters into it; just as through a funnel wine is poured into a container, so also venom and corruption are distilled to the depth of the heart by the melody. To avoid the abuse of music we must avoid licentious songs, and “have songs not only seemly, but also holy, which will be like spurs to incite us to pray to and praise God, to meditate on His works in order to love, fear, honor, and glorify Him.” In this context, Calvin’s solution was to learn the Psalms of David.8 Music in the church. Unlike Zwingli, who eventually eliminated all music from the Zurich services, Calvin interprets Scripture’s teachings on singing as warrant for our real vocal song, not just “singing in the heart.” Calvin says: “We ought also to sing from the heart, that there may not be merely an external sound with the mouth. At the same time, we must not understand it as though he would have every one sing inwardly to himself, but he would have both conjoined, provided the heart goes before the tongue.” Calvin gives several reasons to sing, rather than merely speak, God’s praises. But first, note that Calvin clarifies what is not a reason to sing: “We sing in order to give him thanks – and not in order to produce a solemn ceremony as a meritorious work that we do for God. Those who take this approach are reverting to a sort of Jewishism, as if they wanted to mingle the Law and the Gospel, and thus bury our Lord Jesus Christ.”9 Above all, Calvin insists on singing God’s praises for two complimentary reasons: gratitude to the Savior and obligation to the Lord. First, “He singles out the divine mercy and truth as the subject of his praise, for while the power and greatness of God are equally worthy of commendation, nothing has a more sensible influence in stimulating us to thanksgiving than his free mercy; and in communicating to us of his goodness he opens our mouth to sing his praises.” And also, “It is indeed the duty of all men to sing praise to God, for there is no person who is not bound to it by the strongest obligations; but more lofty praises ought to proceed from those on whom more valuable gifts have been bestowed. Now, since God has laid open the fountain of all blessings in Christ, and has displayed all spiritual riches, we need not wonder if he demand that we offer to him an unwonted and excellent sacrifice of praise.”10 Beyond this, Calvin gives many other motivations for singing, such as in response to the consolation of God’s sovereignty: “His divine power ought justly to strike terror into the wicked, so it is described as full of the sweetest consolation to us, which ought to inspire us with joy, and incite us to celebrate it with songs of praise and thanksgivings.” We should sing for God’s faithful promises: “When, therefore, the Prophets bade the Church to sing to God and to give thanks, they thus confirmed the promises made to them… therefore they could boldly join in a song of thanks to God, as though they were already enjoying full redemption; for the Lord will perfect what he begins.” More pragmatically, singing is for mutual edification: “Here we see the true use of hymns: we are to encourage one another to celebrate and magnify the name of God in our hymns (Eph. 5:19-20).” So great a priority was this for Calvin that of all the complaints he had with the church of Geneva when he arrived, he drew up four points of reform in the Articles of 1537, and one of them was: “Further, it is a thing very expedient for the edification of the Church, to sing some psalms in the form of public devotions by which one may pray to God, or to sing his praise so that the hearts of all be roused and incited to make life prayers and render like praises and thanks to God with one accord.” In addition, singing in worship is a more concentrated for of expression, and can therefore be an aid to worship: “And surely, if the singing be tempered to that gravity which is fitting in the sight of God and the angels, it both lends dignity and grace to sacred actions and has the greatest value in kindling our hearts to a true zeal and eagerness to pray.” Calvin calls on believers to follow the example of the early church and to avoid the distorted practice of the Roman Catholic Church: “There are the psalms which we desire to be sung in the Church, as we have it exemplified in the ancient Church and in the evidence of Paul himself, who says it is good to sing in the congregation with mouth and heart…Moreover it will be thus appreciated of what benefit and consolation the pope and those that belong to him have deprived the Church.”11 Another interesting motivation is presented in the form of an argument for the singing of God’s praises from the fact that we are created the image of God. “Moreover, since the glory of God ought, in a measure, to shine in the several parts of our bodies, it is especially fitting that the tongue has been assigned and destined for this task, both through singing and through speaking. For it was peculiarly created to tell and proclaim the praise of God.” In other words, singing the praises of God is part of man’s task in carrying out the moral perfection involved in the imago Dei.12 To sum up this installment, Calvin considered music a great gift of God with practical and pleasurable characteristics. It should be used as our response to God’s goodness, as part of our obligation as the image of God and covenant members, and as a witness to the body of Christ as well as to the world. Calvin has much more to say about the implications of this and the role of music in the church, which will be brought out in Part Two of this introduction next month. This summary is based on the larger unpublished paper, “Calvin on Music,” by N. Seth Nelson (San Antonio, 2006). This is a historical paper, not a theological one. It is not intended to judge the views of Calvin as good or bad, but merely to summarize what he taught. 2 Epistle to the Reader from Calvin’s Form of Prayers, trans. Charles Garside as an appendix in “The Origins of Calvin’s Theology of Music: 1536-1543,” in Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, 69:4 (August, 1979), 31-33. Comm. Ps. 104:33. Serm. II Sam. 6:1-7. All commentary quotations are from the set translated by John King (Grand Rapids: Baker Book House, 1996). The sermon on II Samuel was translated by Douglas Kelly (Carlisle: Banner of Truth Trust, 1992). 3 Serm. II Sam. 6:1-7; Comm. Eph. 5:19; Dan. 3:2-7; Isa. 42:10. 4 Comm. John 6:15; Matt. 15:1; Amos 2:23; Matt. 22:21; Serm. II Sam. 6:1-7. 5 Comm. Isa. 5:12; Institutes of the Christian Religion, trans. Ford Lewis Battles, ed. John McNeill (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1960), 3.9.3. 6 Epistle; Comm. Gen. 1.27. 7 Comm. Ps. 119:54; Isa. 52:9; Jer. 31:7, 4; Luke 8:52; Serm. Job 21:7-12. Cf. Serm. Job 21:13-15. The sermons on Job were translated by Arthur Golding in 1574 (London: Banner of Truth Trust, 1993). 8 Comm. I Cor. 14:7; Epistle. 9 Comm. Col. 3:16; Serm. II Sam. 6:1-7. 10 Comm. Ps. 138:2; Isa. 42:10. 1 11 Comm. Ps. 22:13; Zech. 2:10; Serm. II Sam. 6:1-7; Articles Concerning the Organization of the Church in Calvin: Theological Treatises, trans. J. K. S. Reid (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1954); Inst. 3.20.32. 12 Inst. 3.20.31.