17.Translational Control

advertisement

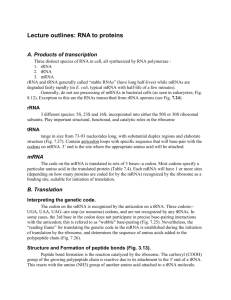

Lecture 17. Translational control of gene expression Flint et al., Chapter 11 BSCI437 Outline 1. Introduction 2. Eukaryotic protein synthesis 3. Viral translation strategies 4. Regulation of translation during viral infection Introduction All viruses must use the host translational machinery to make viral proteins. Translation is the primary battleground between virus and host cells. Theory 1: Eukaryotes evolved monocistronic mRNAs and nuclei as ways to compartmentalize mRNA production from protein translation as an antiviral mechanism. In the Nucleus: pre-mRNA transcription 5’ end capping 3’ end tailing Splicing (and marking of mRNAs with proteins) In the Cytoplasm: Translation of mature mRNAs. Viruses (RNA especially) Enter cell via cytoplasm mRNA = genome Separating mRNA production from translation provides a way for cells to mark mRNAs as their own. Of course, viruses have evolved within these parameters, and have actually figured out how to use this to their own advantage. Cells have in turn responded…and the battle continues. Theory 2: in the pursuit of genome minimization, viruses have evolved unique translational mechanisms Viral genomes are limited in size by volume constraints of capsids Viral genomes evolve toward the small Can shrink genomes by overlapping or nesting genetic information Translational recoding: 1. Allows cellular translational apparatus to decode overlapping open reading frames 2. Allows regulation of viral protein stoichiometries Polycistronic mRNAs: allow multiple proteins to be synthesized by a single mRNA Eukaryotic protein synthesis Eukaryotic mRNAs (Fig. 11.1) Monocistronic 5’ 7MethylGppp caps 3’ polyA tails Spliced Ribosomes (Fig 11.2) 2 subunits: 60S + 40S = 80S Composed of rRNA + proteins. Catalytic activity in rRNA. tRNAs: adaptors between genetic code and protein sequence. Accessory proteins (Table 11.1) Called “factors”. Required for the 3 stages of translation: 1. Initiation (eIF) 2. Elongation (eEF) 3. Termination (eRF) Translation initiation (Fig. 11.3) 1. Multiple eIF factors recognize and bind to 5’ 7MethylGppp cap structures 2. These interact with polyA tail 3. Form a ‘closed loop’ structure: translation competent 4. 40S + initiator tRNA + an eIF (‘ternary complex’) recognizes and binds to closed loop only 5. Ternary Complex “scans” downstream (3’) to AUG in “good” context. 6. 60S joins up to make 80S ribosome. 7. eEF’s bring tRNAs to ribosome, and aid translocation Translation elongation (Fig. 11.7) 1. eEF1 complex brings aminoacyl-tRNA (aa-tRNA) to ribosomal A-site 2. Correct codon:anticodon fit induces GTP hydrolysis. aa-tRNA locked in 3. Incorrect fit…no hydrolysis…aa-tRNA drifts off (proofreading) 4. Peptidyltransfer occurs in large subunit: rRNA catalyzed 5. eEF2 promotes translocation via GTP hydrolysis 6. Ribosome moves precisely 1 codon downstream 7. Elongation cycle starts anew Translation termination (Fig. 11.8A) 1. Termination codon enters A-site 2. No cognate tRNA 3. eRF3/eRF1 complex enters A-site 4. Stimulate peptide bond hydrolysis from peptidyl-tRNA 5. No acceptor in A-site 6. Peptide released from ribosome. The closed loop model (Fig 11.8C) 5’ and 3’ ends of mRNA are linked by interactions between protein factors to form a translationally competent mRNP THE DIVERSITY OF VIRAL TRANSLATION STRATEGIES (Fig. 11.9) Initiation. General point Initiation is a double edged sword By requiring mRNAs to have special properties in order to be translated, cells have made the job harder for viruses. However, in evolving to circumvent these requirements, viruses have opened up new vulnerabilities for cells. Viral initiation strategies 5’ end dependent Viral mRNAs can obtain 5’ caps o By nuclear transcription (e.g. Retroviruses) o By cap-stealing in the cytoplasm (e.g. Influenza) Viral mRNAs can have cap mimics o e.g. Picornaviruses covalently attach a protein (VPg) to the 5’ ends of their mRNAs. VPg can interact with eIF factors, fulfilling the function of the cap. 5’ end dependent Alternative translational start site selection “Leaky scanning”: High frequency of ribosomal bypass of first AUG codons placed in poor contexts. Enables initiation at more than one open reading frame. Increases coding potential. Fig. 11.11 Methionine-independent initiation: viral mRNA contains a tRNA like structure that interacts with the ribosome. Directs ribosome to initiate at a specific location within the mRNA (Fig. 11.4B). Ribosome “shunting”: although ribosome binds to the 5’ end, strong mRNA secondary structures make the ribosome bypass or shunt around the first AUG to initiate further downstream 5’ end independent initiation: Internal Ribosome Entry Site Elements (IRES elements) (Fig. 11.4) Special secondary structures in viral mRNAs can interact with ribosomes, directing them to initiate internally on the mRNA. Come in all shapes and sizes. Advantage of 5’ end independent translation (Fig. 11.18) Virus encoded factors can knock out cap-dependent initiation. Examples include: o Viral proteases cleave eIF factors. o Viral kinases/phosphorylases alter phosphorylation of eIF factors Shut down translation of host mRNAs Only viral mRNAs get translated. Elongation Cellular mRNAs are monocistronic: 1 gene, 1 protein. One way to increase information content of mRNAs is to encode multiple proteins: polycistronic. Viruses have evolved many strategies. Polyprotein synthesis (Fig. 11.10) Viral mRNA encodes many proteins in one long open reading frame This gets cleaved by viral proteases into many smaller proteins. Ribosomal frameshifting (Fig. 11.14) Viral mRNA contains overlapping reading frames Sequences and structures on viral mRNA make ribosome slip. Resulting shift in reading frame directs ribosome into downstream open reading frame Termination A genome condensation strategy Keep ribosomes on a viral mRNA after termination This allows them to translate additional open reading frames. Translation reinitiation (Fig. 11.12) Ribosomes normally fall off of mRNAs at termination Viruses have evolved strategies to prevent this. Allow ribosomes to stay on mRNA and initiate again downstream Termination of suppression (Fig. 11.13) Viral genome has back to back genes separated by a termination codon. Viruses have evolved mRNA sequences and structures that fool ribosomes into reading through termination codons at set rates.