On Origins of Korean supnita and Japanese desu/masu

advertisement

1

On Origins of Korean supnita and Japanese desu/masu:

Deriving Addressee Honorific Markers

from Verbs of Announcements*

Alan Hyun-Oak Kim

Southern Illinois University at Carbondale

1. Introduction

In this study I am concerned with a particular aspect of the theory of grammaticalization--the question of conditions licensing grammaticalization, more specifically, as Traugott and

Heine (1991:7) put it, “given that a form A exists, what is its potential for becoming

grammaticalized, and how do we know when this is happening?”

The present paper is organized in four sections. Following this introduction, in Section 2 I

establish a working hypothesis in order to account for grammaticalization involved with

honorific verbs of ‘saying/telling.’ In Section 3, I show evidence from Korean and Japanese

to support the hypothesis. Section 4 is my conclusion.

2. A Working Hypothesis

The hypothesis, with which I work in this paper is as follows:

(1) Hypothesis on Sentence-final Polite Markers

If a language has verb-final word order, and if it has a system of

honorification (as seen in Korean and Japanese), verbs of communication

(such as ‘say’, ‘tell’, ‘inform’) tend to undergo grammaticalization along

two pathways: (i) shifting the lexical categories; and (ii) shifting in

functional categories of the following:

(2)

A. Changes in Lexical Categories

I. Lexical Verb → Auxiliary Verb

II. Auxiliary Verb → Grammatical Morpheme

B. Changes in Functional Categories

I. Subject Honorifics

→ Non-subject Honorifics

II. Non-subject Honorifics → Addressee Honorifics

3.

Evidence from earlier Korean and Japanese data

3.1. Standard Modern Korean supni-ta

The Korean sentence-final polite marker supni may be separated into two segments: sup

*

This paper is a revised version of Kim (2006). I am grateful to Kaoru Horie, Kyoung-Sun Hong, Gregory

Iverson, Chin-Wu Kim, Hae-Yeon Kim, Hyun-Sook Kim, Joungmin Kim, Young-Key Kim-renaud, Tetsuharu

Moriya, Mira Oh, Byung-Soo Park for their valuable comments and encouragement. Dale Kim and Leonel Bender

gave me editorial help, which I thank. My deepest gratitude goes to Professor Fernando Torres and the devoted

members of his organizing committee of the 15th ICKL on the campus of Universitat autonoma de Guadalajara,

Jalisco, Mexico.

2

and ni. We owe the two-part analysis of supni previous studies by two authors, Ogura (1929

and elsewhere) and H. K. Kim (1947 and elsewhere). In his 1929 and 1938 diachronic studies

of Hyangga, Ogura isolated two series of morphemes sp (5a) and i (5b) as separate

entities, and he suggested that the former may be derived from Old Korean slp, and also that

both sp (5a) and i (5b) have developed to the present-day (su)p and ni, respectively.

In this conjunction, Ko’s (1944:125) following observation is intriguing. Namely, the form

p-ni is found only from the late 19th C. The earlier appearance of sup-ni may be explained

naturally from the assumption that sp is ancestral to the modern sup-ni form, which serves as

the base of the p-ni form.

H. K. Kim notes that the verb sp became the marker of Referent Honorifi-cation,

particularly Non-subject Honorification, and further it had lost its original function by

resulting in a simple grammatical morpheme of Addressee Honorification incorporated into

the second component i. The grammaticali-zation through the categorical conversion is said

to take place during the late 15C and the early 16C. More detailed derivational paths of the

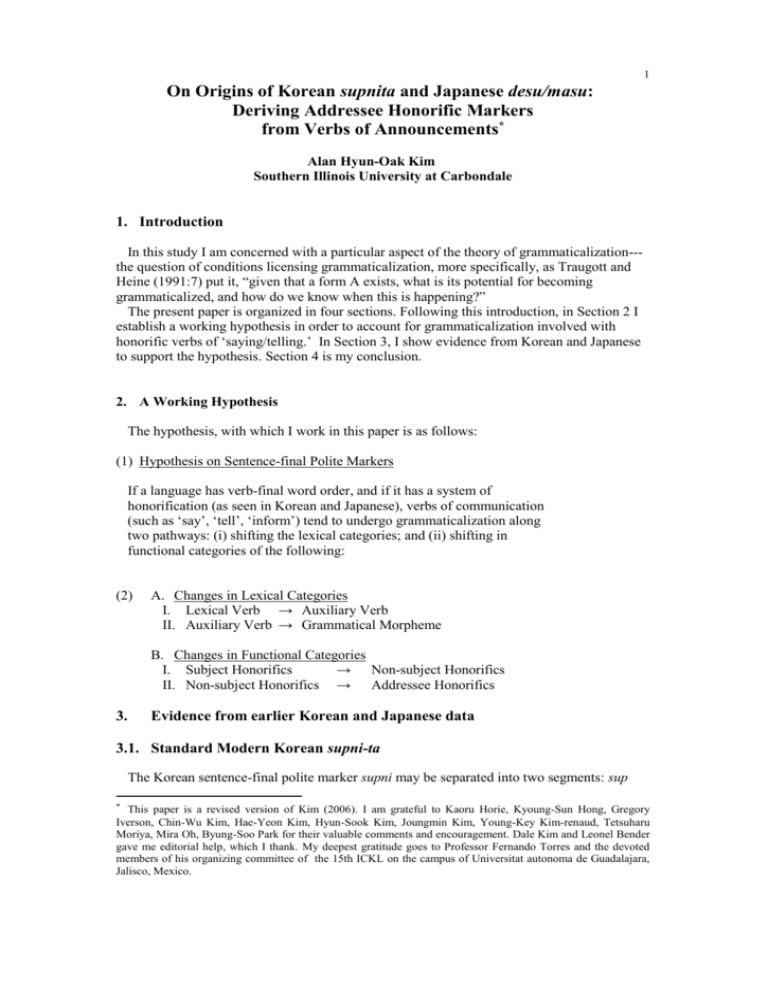

two morphemes can be seen on Heo’s (1963) chart below.

Shilla/Koryo

Subject

Honorific

Referent

(DO/IO)

Honorific

Honorific

Addressee

Late 15C/Early 16C

賜 → 教(是)

白教(時)

白

音

→

→

→

→

→

→

→

sp

i →

賜立→ 受勢→

少時

si

zsi

17C

si

psi

sp1

→

sp2

→

{i, i} → {i, i} →

syosyə

→

syosyə

18C & thereafter

→

→

si

apsi/opsi

(yeccu-ta/pweop-ta)

op/sap/jap

(hanaita/haopnai-ta)

(e.g. kali-ta/ kapni-ta)

→

sose

Table 2: Historical changes in sp and ŋi (Heo 1963)

Heo’s chart above is particularly significant on four points. (i) Three modes of honorification

are identified; (ii) The split of sp1 and sp2 around the 17th Century (The subscript is

devised by AHK.); and (iii) Making distinction between two subtypes in Addressee

Honorification; (iv) Isolating the honorific imperative form sose. Heo’s identification of sp1

and sp2 is critical from the grammaticalization point of view. The process of verb to

morpheme is neatly shown in his analysis. The form sp1 maintains the status of a fullfledged verb ‘to tell something to Superior’ up to Modern Korean with the original meaning

intact. The second sp2 , on the other hand, reduced its form to that of an auxiliary verb from

the 18th century and eventually it turned into the functional polite marker (su)p-ni-ta, the

sentence-final function word for Addressee Honorifics. The last item sose, which seems to

correspond to Ogura’s so-series (5c), appears exclusively in imperative (‘the speaker’s

petition for the superior’s merciful favor’). Thus, (su)p-ni may be said to have undergone

stages of I and II of the A category and I and II of the B category as well. 1, 2

3. Evidence from earlier Korean and Japanese data

3.1. Middle Korean slo-ta and Classical Japanese soro

3

Evidence suggests that the present day addressee honorific markers such as Korean

(su)pni-ta and Japanese desu/masu, seem to be derived from full-fledged verbs of

communication.

In Middle Korean texts, there are many occurrences of the non-subject honorific auxiliary

sp-ta or its variant slo-ta, ‘convey messages to Superior,’ which is first observed by Ogura

(1929). The auxiliary verb sp-ta and its variants are exemplified below, which I borrow

from Lee & Im (1983:228).

(3) Sinha-i nimgm-l top-sʌpa [sp-ta]

sibjects-NOM King-ACC help-HONO-and

‘Ministers assist the king, and ….’ (Seogbosang Jeol 8)

(4) Taejung-tul-i…puthyə-ll

po-zapae s təni [zp-ta]

people-PL-NOM Buddha-ACC looked-at-HONO PAST-then

‘When People looked at Gautama….’ (Seokbosang Jeol 13)

(5) Ayu-i…….sejon-s anpu-ll mut-jap-ko [jp-ta]

Ayu-NOM Shakamuni’s safety-ACC ask-HONO-and

‘When Ayu asked about Shakamuni’s safety……’ (Seok Jeol 6)

Unlike sp-ta, the lexical item slo-ta in (6) below is used as a full-fledged di-transitive verb

‘reports/tells messages to a third party who is superior to the speaker.’ (Quoted from Nam

1997: 936)

(6) ms il-l

slolila

what thing-ACC say-would

‘What should I say?’ (Songgang Gwangdong Byeolgok)

(7) k paski sto

syəl-un il-ll jsehi slolila

that other than again sad thing-ACC in detail tell

‘Tell (your Senior) in detail about all your sad stories.’ (Boguk. Haein. 31)

(8) ilhum-l sloti syəngin-ila

name-ACC say holy person-be

‘He is called a sage.’ (Weongak sang 2:2)

(9) msik-l

kchoa tliko

slo ti

dishes-ACC prepare submit-and said that…..

‘(She) prepared dishes to put them in front of him and said …’ (Oryun1:54)

In (9), the noun msik ‘food/dishes’ is Direct Object of the lexical verb slo-ta and Superior

as Indirect Object thereof. Recall that Old Korean slp (白 in the Idu transcription) was

originally a di-transitive verb with the meaning of yeccwu-ta ‘tell an honoree about

something’ or pweop-ta ‘have an audience of Superior.’ Modern Korean salwe-ta/salœ-ta

goes back to slp, according to Pyojungugeo Daesajeon ‘Standard Unabbreviated Dictionary’

(1999:3110). Heo (1963) claims that slp underwent two separate paths: (i) it changed to

slo-ta and further became salœ-ta with its original meaning intact; and (ii) it turned into an

auxiliary verb of Non-Subject Honorification and eventually became a grammatical marker of

Addressee Honorification in Korean.

As for Classical Japanese polite marker sourou, its usage in letter-writing was extremely

4

popular in Medieval Japan and throughout the Japanese feudal periods up until the turn of

the 19th century.

The Japanese politeness auxiliary verb sourou is suffixed to the infinitive (the literary

negative infinitive) for addressee-oriented honorification. It had established itself as a bound

morpheme (or auxiliary) far back in pre-Middle Japanese. Particularly, it became omnipresent

in pre-modern Classical Japanese spoken among samurai intellectuals of the Edo period 1.

Thus, Old Korean referent (non-subject) honorific verb slp-ta underwent

grammaticalization (verb → grammatical bound-morpheme) to become an Addresseeoriented polite marker. Classical Japanese sourou may be contrasted as shown in Table 1

below.

CJ

sourou

MK

slo-

Phonological

shape

sibilant/liquid

and low vowels

sibilant/liquid

and low vowels

Meaning

‘say’ ‘tell’

say’ ‘tell’

Indirect object

referred to

Superior to the

speaker

Superior to the

speaker

Grammaticalization

Processes

Lexical Verb → Object Hon →

Addressee Hon

Lexical Verb → Object Hon →

Addressee Hon

Table 1: Correspondences between CJ sourou and MK slo-ta

It is particularly remarkable that both Old Japanese sourou and earlier Korean slounderwent the three-stage grammaticalization paths in a parallel way, namely, Phase I (Fullfledged lexical verb) → Phase II (Non-subject (object) honorific auxiliary verb) → Phase III

(Addressee honorific morphemic marker).

On the basis of etymological resemblance and diachronic parallelism in

grammaticalization, one might suggest that Classical Japanese sourou and Middle Korean

slo-ta (for that matter, Old Korean slp, à la Ogura 1938) shared a genetic ancestor at an

earlier time.2

3.2

Classical Japanese mousu

One will find the Japanese verb mousu is highly homophonous, and there are three distinct

usages. Let us call them mousu1, mousu2, and mousu3, and their functions are:

(10) a. mousu1 (Lexical verb ‘to serve Superior,’ ‘to wait on Superior,’)

b. mousu2 (Lexical verb ‘to tell Superior,’ ‘to say to Superior,’ )

c. mousu3 (Auxiliary for Referent (IO) Honorifics with loss of the

original meaning)

Mousu1 is a full-fledged transitive verb having the meaning ‘to serve Superior,’ to attend

Superior,’ ‘to accompany Superior’, etc. as seen below.

(11) Mifune sasu situo-no tomo-ha kawa-no se

mouse. (Man 4081)

boat draw servants-TOP river-shallow water inform

‘Boatman, explain to your master that the river is shallow.’

(by Nakanishi 1981)

Mousu2 is equivalent to ‘tell’ or ‘say’ in English. The verb expresses Speaker’s deference

It is said to be related originally to the noun samurai. Satō (1962) shows the etymological development of

sourou as in (13) below.

(13) samorapu > saburapu > saurapu > sourou (Satō 1962: 2.138-9 from Martin 1975:1039)

2 Cf. Satō Kiyoshi (1962) for a different analysis.

1

5

toward Superior as Indirect Object (not Superior as Addressee) in a sentence.

(12) Sin dainagon-mo hira-ni mausare keri

new chief counselor-too sincerely say-PAST

‘The newly appointed Chief Councilor of State also said so.’

[Heike 1] (Kōjien 1981:2183)

The third kind (mousu3) is attached to the main verb expressing Speaker’s deference toward a

referent Superior, i.e. Indirect Object, and its function is merely that of an auxiliary verb with

no specific meaning of ‘saying,’ as shown in the following examples.

(13) Sensei-no otaku-wo

o-tazune-mousi-ta.

teacher-GEN house-ACC

visit- HON-PAST

‘I visited my teacher’s home.’

The item mousu3 does not seem to have the meaning of announcement, and we may

conjecture it may have derived from either mousu1 or mousu2. The former may have changed

to an auxiliary by keeping its semantics of ‘servitude’ intact. The second choice, i.e. mousu2

may have lost the original functions of full verb status as well as the semantics of saying

altogether. Of the two, mousu1 would cost less for the subsequent grammaticalization in

comparison to mousu2 in terms of the degree of the relevance, which is roughly similar to

Yoshida’s (1971) suggestion that the modern masu might have its root in mawosu ‘tells,

humbly does.’ Note that the analysis proposed here has a two-stage process, namely, first,

from verb to auxiliary, then from the auxiliary to bound morpheme of the polite marker masu.

Now let us turn to Korean data corresponding to Japanese maosu. The Korean lexical verb

moesi-ta or its variants moysi-ta/mōsi-ta have one meaning ‘to serve Superior,’ but in two

different functions, that is, the former as a lexical verb and the latter as an auxiliary verb, as

exemplified for the first kind in (14) and for the second in (15) below.

(14) K. Ce pang-ey cosang

sincwu/wiphay-ka mōsye-ce

iss-ta

J. Ano heya-ni senzo-(no) ihai-ga

matur-are-te aru

that room-in ancestor

mortuary tablet-NOM enshrine-PAS-be

‘They enshrined their ancestral tablets in that room.’

(15) K. Cal annay-hay mōsi-e-la

J. Yoku go-annai mosi-age-yo

well guide serve-IMP

‘Give a nice guide (to the guest).’

Functions of these three different mousu are summarized below.

(16)

Japanese

a. mousu1 ~

b. mousu2 ~

c. mousu3 ~

Korean

moesi-ta1

moesi-ta3

Functional Category

(full verb of servitude to Superior)

(full verb of reporting to Superior)

(auxiliary verb of servitude to Superior)

Two things are noteworthy: first, the resemblance between the Korean and Japanese data is

quite remarkable in terms of their phonological shape and semantic/ pragmatic functions (‘to

serve Superior’). Second, the Korean counterpart of mousu2 is missing in (16b). Korean

speakers use a verb salwe-ta or Older slo-ta in the place of mousu2. One can assume that

Japanese mousu2 might have an origin entirely different from mousu1. Namely, mousu2 may

be related to Middle Korean malsm or malsam, which corresponds to Japanese o-kotoba

‘word, speech, language or Superior’s message.’ The following seems to support this thought:

6

(i) the phonological resemblance between Old Japanese marasuru and the Middle Korean

noun malsam; (ii) a parallelism in a sentence-final idiomatic expression: Korean ~la-nun

malssum-i-yeyo and Japanese ~ to iuu koto desu-yo ‘that’s the way it was’: (iii) a parallelism

between the sentence-filler na-mosi (‘you know’) in Japanese dialects (Prefectures of

Tokushima, Gifu, Gunma etc.) and colloquial Korean la-n-malssum-i-ya. (Cf. a detailed

discussion in Kim 2006.)

3.3 Middle Korean op-sose and Old Japanese asobase

Pervasive occurrences of the phrase op-sose are found in Middle Korean material, Buddhist

narratives in particular. The honorific imperative form op-sose is frequently found in prayers

even today. Now let us consider the following:

(17) Melli ttena-ka-nun

ku-eykey unchong-ul payphwule cwu-si-op-sose.

far away leave-ATTR him mercy-ACC provide give-HON-please do

‘Give thy mercy to the person who is going far away.’

In (17), the speaker asks the Lord to give His mercy to a third person (not to the speaker

himself) in the sentence. The imperative mood expresses the speaker’s soliciting mercy of the

addressee (Lord).

(18) Yehowa-ye cwu-uy pun-ulo

na-lul kyenchayk-haci ma- op-si- mye

lord

Your anger-with me

rebuke

do-not please-and

cwu-uy cinno-lo

na-lul cingkye-ha-ci ma- op-sose

Your

hot displeasure-with me

chasten-do-not

please

‘Lord, do not rebuke me in Your anger, nor chasten me in Your hot

displeasure.’ [The Old & New Testament (Psalms 6:7) The King James

Version and Korean Revised Hangul Version), Daehan Seongseo

Gonghoe. 1985:806]

The above is a quotation from the Old Testament. This type of honorification survives only in

literary writing and in dialects of a much simpler form.

At this point, I would like to invite the reader to consider an honorific format of pre-modern

Japanese somewhat similar to Korean archaic op-sose. Many dictionaries define asobas-e as

the imperative form of asobas-u, a full-fledged intransitive/transitive honorific verb ‘play,’

‘go hunting,’ or ‘play musical instruments.’ The item can also be used as an auxiliary verb.

For instance, Kōjien (1981:40) gives examples O-tori-asobas-i-ta ‘(He) took it’ and Go-ran

asobas-e ‘Please take a look, where o-tor-i is a gerund form prefixed with the honorific

marker and go-ran is in the form of Prefix+Noun. According to Tsujimura (1968), the word

asobasu is the oldest of the nine honorific expressions in earlier Japanese. Two examples are

from premodern Japanese.

(19) kotira-he o-hairi-asobase

this way-to enter-HON

‘Please come in this way.’

[Sugahara Denju Tenarai-kan 4.] quoted from Shinchō Kokugo Jiten. 36

(20) mohaya kidukai-asobasu-na

no longer worry-HONO-don-not

‘Do not worry any more, Sir.’

7

[Chikamatsu, Koori no sakutan 3] quoted from Iwanami Kogojiten 29.

It is particularly noteworthy that many examples are presented in the imperative form, i.e.

commanding expression to Superior or petitioning. The auxiliary asobase does precisely the

job of‘requesting to Superior’ in Japanese. The petition expressed by asobase is particularly

suitable in honorifics. It magnified the Superior’s authority to grant his subordinate’s petition.

In (21) below, where Korean si-op-so-se and Japanese asobase are contrasted, the segment

ha-si (do+subject honorific marker) is supplemented to the base form as seen in (48a).

(21) Korean:

Japanese:

ha si

si

a

a

o p so

se

o ba so

e

syo ba soe

so

ba se

[Insertion of low vowel a]

[de-palatalization of syo

and delabialization of glide oe]

Each of the four syllables in the contrasted set is in fairly good correspondence, if we assume

two historical processes, namely the a-insertion, the syo-depalatalization, and the oedelabialization, in addition to the adopting the light verb ha ‘do’ suffixed with the honorific si

marker. Both are in the format (‘petition honorifics’), which involves the notion of causer and

cause discussed above. In the petition honorifics mode, ‘the causer’ is the (humble) speaker,

who solicits his superior’s favor, while the party solicited is Superior, ‘the performer,’ who is

to grant his subordinate’s petition. Consequently, verb-phrase construction like (21a) and

(21b) may involve two sets of honorification, respectively: Non-Subject Honorification (for

Superior as the party requested), and Subject Honorification (for Superior as the causee

performing the imposed demand.)3

4. Concluding Remarks

The notion of grammaticalization is a historic one. The recent revival of the notion has

been productive in the investigation of various functional morphemes in individual languages

of the world. I demonstrate in this paper that the theory of grammaticalization is indeed

instrumental in exploring some aspects of sentence-final politeness markers in languages like

Korean and Japanese.

In this study, a working hypothesis was introduced: verb-final languages like Korean and

Japanese have a grammaticalization process that ‘saying’ verbs may undergo from a fullfledged verb to a functional marker of bound morpheme via a stage of auxiliary verbs. The

study demonstrates that the Korean polite marker (su)p-ni-ta may have two components sup

and ni which may be traced back to Old Shilla lexical verb slp-ta ‘to let Superior know

about x,’ of Referent (In-direct Object) Honorification and i, a bound morpheme of the

same Referent Honorification. The original sources of grammaticalization of Japanese polite

markers desu and masu are explored. Both forms are seemingly proved to be the end-products

of grammaticalization. Other items of Japanese, such as sourou, mousu, asobasu, etc. are

originally honorific verbs of communication (to report, to announce, to inform, and the like)

are highly susceptible to grammati-calization, as the hypothesis predicts. The syntactic

environment (i.e. the sentence-final position of these communication verbs) is by nature

found in the sentence-final position in Korean and Japanese, and, as a result, it has relatively

more probability of change. Since honorification is viewed as a linguistic ritual or symbolism,

3

This dual nature of the honorification mode involved in the expressions such as one in (48) above has given rise

to considerable confusion and discussions in the literature (H. K. Kim 1954 elsewhere; Heo 1954 elsewhere;

Cheun 1958; Ahn 1961, 1982; S. N. Lee 1954; S. O. Lee 1973; I. S. Lee 1974, among others.)

8

its stylization, the reason for which might be that such stylization (grammaticalization to

bound morphemes in the simpler forms) will make participants exercise rituals in simpler but

more effective ways with less cost. Findings also seem to indicate that some Japanese

functional markers are found to have their origins unexpectedly in earlier Korean data.

REFERENCES

Ahn, Byung-Hee. 1961. Juchae gyeomyang-beop-ui jeopmisa -sp-e daehayeo. Jindan Hakpo 22: 105126.

Cheun, Jae-Gwan. 1958. Sp-ttawi Kyeong-Yang-sa-ui Sango. Kyungpuk Dae-hak-gyo Ronmun-jip,

2:117-137. ‘Essays on Subject and Referent Honorification of sp, etc. in Collection of Treatises,

Kyungpuk national University 2: 117-137.

Choe, Hyoen-bae. 1958. Uri malbon ‘Our grammar.’ Seoul: Ulyu Munhwasa

Heo, Ung. 1954. Jondae-beopsa: Gukeo Munbeopsa-ui han tomak. Seonggyun Hakpo. 1: 139-207.

Heo, Ung. 1962. Jondae-beop-ui munje-rul dasi ronham. Hangul 128:5-62.

Heo, Ung. 1975. Uri ye s malbon. Seoul: Sae Munhwasa.

Kim, Alan Hyun-Oak. 2004. Nihongo no keigo taikei no gensoku to meta-gengoteki bumpō

(‘Principles and Meta-Linguistic Grammaticalization in the System of Japanese Honorifics’) In

Taro Kageyama and Hideki Kishimoto (hen) Nihongo no bunseki to gengo ruikei - Shibatani

Masayoshi Kyōzyu Kanreki Ronbunshu (‘Analyses of Japanese and Language Typology:

Festschrifts for Professor Masayoshi Shibatani’)26-46. Tokyo: Kuroshio Publishers.

Kim, Alan Hyun-Oak. 2006. Grammaticalization in sentence-final politeness marking in Korean and

Japanese. In Susumu Kuno et al. (eds.) Harvard Studies in Korean Linguistics XI. Department of

Linguistics, Harvard University. 72-85.

Kim, Hyeong-Kyu. 1954. Gukeo(hak)-sa. Seoul: Baekyungsa

Kim, Hyeong-Kyu. 1960. gyeogyang-sa-wa ‘ka’ jugyeok to munje. Hangul 126:7-18

Kim, Hyeong-Kyu. 1962.Gyeong-yang-sa munje-ui jeron. ‘The issues of Subject honorification and

referent honorification revisited.’ Hangul 128: 60-73.

Kim-Renaud, Young-Key. 1990. On banmal in Korean. In ICKL 7: Papers from the Seventh International Conference on Korean Linguistics. Osaka, Japan: ICKL and Osaka University of

Economics and Law. 232-255.

Ko, Yung-Geun. 1974. Hyeondae gukeo-ui jonbi-beop-ey daehan yeongu. Eohak Yeongu 10.2.

Lee, Ik-Sup and Hongbin Im. 1983. Gukeo-munbeop-on. Seoul: Hakyeonsa

Lee, Kyu-Chang. 1992. Gukeo Jondae-beop-ron. Seoul: Jipmundang.

Lee, Sung-Nyung. 1954. Gojeon Munbeop. Ulyu Munhwasa.

Lee, Sung-Ok. 1973. Gukeo munbeop chaekye-ui sajeok yeongu. Seoul: Iljogak.

Marin, Samuel E. 1975. A reference grammar of Japanese. New haven & London: Yale University

Press.

Martin, Samuel E. 1992. A Reference Grammar of Korean. Rutland, VT and Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle

Company.

Nishida, Naotoshi. 1987. Keigo ‘Honorification.’ Kokugo sōsho 13. Tokyo: Tokyo-dō.

Ogura, Shinpei 1938. Chosengo ni okeru kenjōho/sonkeigo no jodōshi. Tōyōy bunko ronshōū 26.

Satō, Kiyoshi. 1962. Nihon bumpō yōsetsu, Kogo-hen. ‘Essentials of Japanese grammar: the historical

aspects’ 2 vols. Tokyo: Nihon Shoin.

Seo, Jeongsu. 1984. Jondaebeop-ui yeongu: hyeongae daeu-beop-ui chegye-wa munje-jeom. ‘A study

of honorifics: The current honorification system and its problems.’ Seoul: Hanshin Munhwasa.

Seong, Gi-Cheol. 1970. Gukeo daewubeop yeongu ronmunjijp Chungbuk Dae-hakgyo 4. 78-99.

Traugott, Elizabeth and Bernd Heine. 1991. Approaches to Grammaticalization. Volume I: Focus on

Theoretical and Methodological Issues. Amsterdam/ Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Co.

Traugott, Elizabet C. and Richard B. Dasher. 2002. Regularity in Semantic Change. Cambridge, U.K.:

Cambridge University Press.

Tsujimura, Toshiki. 1968. Keigo no siteki kenkyu. Tokyo: Tokyodo.

Yoshida, Kanehiko. 1971. Gendaigo jodō-shi no shi-teki kenkyū. Tokyo: Meiji Shorin.

Dictionaries:

9

A Korean-English Dictionary. 1967. eds. by Samuel E. Martin et al. New Haven and London: Yale

University Press.

Gyohak Go’eo Sajeon. 1997. ed. by Gwang-Wu Nam. Gyohaksa.

Iwanami Kogo Daijiten. 1974. ōno Susumu hoka. Iwanami Shoten.

Kōjien. 1976. ed. by Izuru Shinkura. Iwanami Shoten.

Kadokawa Kogo Jiten. 1981. eds. by Senichi Hisamatu et al. Kadokawa Shoten.

Pyojun Gukeo Daesajeon. (sang-jung-ha) 1999. Gukrip Gukeo Yeonguweon. Dusan Dong-A.

Shinchō Kikugo Jiten. 1980. eds. by Toshio Yamada et al. Shinchōsha.

Shōgakkan Kogo Daijiten. 1983. Nakada Norio-hoka. Shōgakkan.

Yijoeo Sajeon. 1964. ed. by Chang-Sun Yu. Yeonse Daehakgyo Chulpanbu.

Alan Hyun-Oak Kim

Department of Linguistics, Foreign Languages and Literatures

Southern Illinois University at Carbondale

Carbondale, Illinois 62901-4521, USA

alanhkim@siu.edu

http://mypage.siu.edu/alanhkim

1

One often hears expressions like the following in the dialect of Andong, Kyeongpuk Province (the south eastern part of the

peninsula.)

(6)

Pakk-ey

pi-ka

o

nii- te.

outside-LOC rain-NOM come- POL-SE

‘It’s raining outside.’

(7)

Kwen-sensayng-nim-un caknyen-ey

Kwen-professor-TOP

unthwe-ha- si-ess-

last year-LOC retire-do-

nii-te

SH-PAST-POL-SE

‘Professor Kim retired last

year.’

(8)

Sensayngnim-uy pankawun sosik ce-uy pwumo-nim-kkey

your

wonderful news my parents

yeccwu-ess-

DAT

nii-de

inform-PAST POL-SE

‘I told my parents about your wonderful story.’

Here, the morpheme nii in the above examples are regarded as the modern variant of Middle Korean i, which Nam (1997:1155)

identifies as nii-ta. The following is a Middle Korean example from Nam (1997:1155).

(9)

talom

epsu

i-ta (Nunghay 2:9)

difference exist-not POL-SE

‘There is no difference, Sir.’

(10) ani i-ta, Secon-ha (Nunghay 5:21)

not-be POL-SE Shakyamuni/Gautama

‘No, it is not, Gautama.’

10

As we note in Heo’s chart in Table 2, slp-ta was a full-fledged lexical verb having the meaning of ‘tell Superior about

something,’ from which Referent Honorific auxiliary verbs sap/op/cap and Addressee Honorific polite marker sup are derived.

In contrast, the item i seems to be in existence as an auxiliary verb even as early as in the period of the Shilla kingdom (356935). Therefore, the polite marker i may have gone through grammaticalization of AII and BII but not beyond.