Module Outlines: MSc in Human Communication

advertisement

School of Community and Health Sciences

Programme Handbook

MSc Human Communication

September 2010 – July 2011

Please note: The information in this Handbook is correct at the time of

going to press in September 2010 - the University reserves the right to

make changes in regulations, syllabuses etc without prior notice.

Table of Contents

City University London and you ................................................................................ 5

Purpose of the Handbook ......................................................................................... 5

Who’s who ................................................................................................................. 6

LCS FAX Numbers.................................................................................................... 8

Academic Year .......................................................................................................... 9

Departmental Information ............................................................................................. 9

Communications and how to find out what you need to know ................................ 9

Pigeonholes ............................................................................................................... 9

E-mail....................................................................................................................... 10

University website ................................................................................................... 10

Finding a member of staff to help you .................................................................... 10

Programme Director's office hours ......................................................................... 10

Contingency plans for staff illness .......................................................................... 10

Organisation and Administration ................................................................................ 11

Committee structure for School/Department governance ..................................... 11

MSc Human Communication Programme Management Team ............................ 11

Student Representation in School of Community & Health Sciences ................... 12

Expressing your views ............................................................................................ 12

Student evaluation of teaching ............................................................................... 13

University Complaints Procedure ........................................................................... 13

Student Support .......................................................................................................... 13

Library Information Services ................................................................................... 13

IT Public Services ................................................................................................... 15

Educational Advice and Guidance Service ............................................................ 23

University’s Policy on Student Support .................................................................. 23

Personal Tutors ....................................................................................................... 23

Other sources of support ........................................................................................ 23

Student Centre ........................................................................................................ 24

Students’ Union ....................................................................................................... 24

Centre for Careers & Skills Development .............................................................. 25

Programme ................................................................................................................. 25

Background ............................................................................................................. 25

Aims and Objectives of the Programme ................................................................. 27

Programme Organisation ........................................................................................ 27

Induction .................................................................................................................. 29

Additional activities .................................................................................................. 29

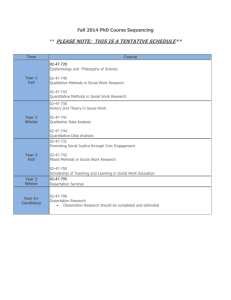

MSc Human Communication Timetable: 2010-11 ................................................. 30

MSc Human Communication Provisional Timetable: 2011-12 .............................. 31

Module Outlines: MSc in Human Communication ..................................................... 32

HCM001 Acquired Language Impairment Module................................................. 33

HCM021 Case-Based Clinical Application Module ................................................ 36

HCM002 Clinical Management Module .................................................................. 39

HCM003 Cognitive Communication Impairments Module ..................................... 41

HCM005 Developmental Language Impairment Module ...................................... 43

HCM007 Dysphagia and Disorders of Eating and Drinking Module ..................... 46

2

HCM008 Evidence-based Practice Module ........................................................... 49

HCM009 Habilitative Audiology Module ................................................................. 51

HCM010 Identity, Inclusion and Living with Disability Module .............................. 54

HCM019 Language Learning and Development Module ...................................... 57

HCM012 Research Design and Statistics Module A ............................................. 60

HCM020 Research Design and Statistics Module B ............................................. 62

HCM016 Speech Acoustics and Speech Perception ............................................ 63

Teaching and Learning Issues ................................................................................... 66

Lectures ................................................................................................................... 66

Conduct in lectures ................................................................................................. 66

Tape recording lectures .......................................................................................... 66

Attendance Policy ................................................................................................... 67

Assessment................................................................................................................. 67

Coursework ............................................................................................................. 67

Guidelines for oral and written presentations ......................................................... 67

Submission of coursework ...................................................................................... 67

Presentation of coursework .................................................................................... 68

Word limit guidelines and penalties for exceeding word limit ................................ 68

Resubmission of coursework .................................................................................. 68

Coursework extensions........................................................................................... 68

Note on the use of IT in preparing coursework ...................................................... 69

Penalties on late or non-submission ...................................................................... 70

Plagiarism ................................................................................................................ 70

Student copyright .................................................................................................... 72

Examinations ........................................................................................................... 72

Guidelines for written examinations ....................................................................... 72

Discipline ................................................................................................................. 73

Cheating .................................................................................................................. 74

University policy on sickness certification .............................................................. 74

Extenuating circumstances ..................................................................................... 74

Assessment Board .................................................................................................. 75

External Examiners ................................................................................................. 75

Return of coursework and release of results ......................................................... 75

Publication and disclosure of examination results ................................................. 76

Failure decisions ..................................................................................................... 76

Appeal procedures .................................................................................................. 77

Application for checking of marks ........................................................................... 77

University Statement on Data Protection ............................................................... 78

Assessment criteria .................................................................................................... 79

Pass marks .............................................................................................................. 80

Overall aggregate .................................................................................................... 80

Distinction ................................................................................................................ 80

Resits ....................................................................................................................... 80

Dissertation (for MSc students only) .......................................................................... 81

General introduction ................................................................................................ 81

Ethical considerations in MSc Research ................................................................ 82

3

Procedures for the submission and examination of MSc dissertations ................ 83

Supervisor’s role ..................................................................................................... 83

Timetable for MSc dissertations ............................................................................. 84

Guidelines for preparation of dissertation .............................................................. 84

Presentation of dissertation .................................................................................... 86

Further reading ........................................................................................................ 86

Notes to students about publishing research ......................................................... 87

Appendix 1: Guidelines for preparation of assignments............................................ 88

Guidelines for directed discussions of research articles........................................ 88

Guidelines for critical review ................................................................................... 88

Guidelines for essays .............................................................................................. 88

Guidelines for poster presentations ........................................................................ 97

Guidelines for referencing work ............................................................................ 100

Appendix 2: Further guidelines for dissertation ....................................................... 104

Broad guidelines for journal articles reporting empirical studies ......................... 104

These typically include the following sections:..................................................... 104

Additional guidelines for dissertations based on qualitative methodology .......... 106

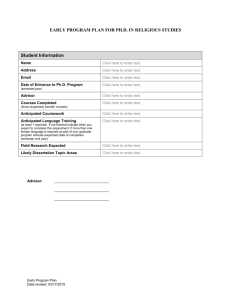

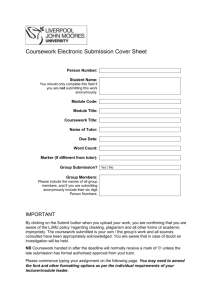

Appendix 3: Forms .................................................................................................... 112

Coursework Coversheet ....................................................................................... 113

MSc Human Communication - Project Proposal Form ........................................ 114

Application for coursework extension ................................................................... 115

Dissertation Extension Request Form .................................................................. 117

Extenuating Circumstances Request Form ......................................................... 119

Appendix 4: Governance structure diagram 2009-10.............................................. 120

4

City University London and you

City University London is committed to providing you with an excellent educational

experience to help you realise your ambitions. Staff and students can work together

to achieve this aim and this document defines what you can expect from City, but

also what City expects from you.

You can find the full version of City University London and You at

https://uss.city.ac.uk/inau-vb/nc/sc/2008_09/238/sc238_item11part2.doc

City will treat you in a professional, courteous and helpful way.

It is our responsibility to:

-

deliver high quality, relevant courses

provide an environment which will help you to be successful

communicate effectively with you and listen to your views

respect the different needs of all our students and be fair, open and

reasonable

You are an ambassador for the University and should behave with honesty and

integrity.

It is your responsibility to:

-

behave in a professional and respectful way in your interactions with other

students, staff, visitors to the University and our neighbours

take your course seriously and seek advice and help if you have any

problems

give us feedback on your experience at City

tell us if you have any specific learning needs or disabilities so that we can

support you

Purpose of the Handbook

The Programme Handbook contains general information about the University, the

School and Department, and more specific information about your MSc programme.

We also offer guidance on a number of teaching and learning issues. We hope that

you find this useful. The Handbook is revised on an annual basis so, if you have any

comments about its layout or content, please contact Shula Chiat, Programme

Director, MSc in Human Communication.

5

Who’s who

Lecturing Staff

Nicola Botting

Bernard Camilleri

Shula Chiat

Naomi Cocks

Madeline Cruice

Lucy Dipper

Barbara Dodd

Celia Harding

Natalie Hasson

Kirsty Harrison

Ros Herman

Julie Hickin

Katerina Hilari

Allen Hirson

Victoria Joffe

Position

Reader

Senior Lecturer

Professor

Senior Lecturer

Senior Lecturer

Senior Lecturer

Professor

Senior Lecturer

Lecturer

Lecturer

Senior Lecturer

Senior Lecturer

Senior Lecturer

Senior Lecturer

Reader

Rachael Knight

Lia Litosseliti

Mary Lee

Abigail Levin

Senior Lecturer

Senior Lecturer

Senior Lecturer

Senior Lecturer

Jane Marshall

Gary Morgan

Lucy Myers

Tim Pring

Penny Roy

Katya Samoylova

Paul Turner

Johan Verhoeven

Roberta Williams

Professor

Professor

Senior Lecturer

Professor

Reader

Lecturer

Senior Lecturer

Reader

Senior Lecturer

Area of academic specialisation

Child Language Impairment (f-t)

Child Language Impairment (f-t)

Child Language Impairment and Linguistics (f-t)

Acquired Neurological Impairment (f-t)

Aphasia / Clinical Enterprise Project Lead

Linguistics (0.5)

Child Speech Impairment (f-t)

Learning Disability (f-t)

Child Language Impairment (0.2)

Motor speech, dysphagia and neurology (f-t)

Deafness & Hearing Impairment (0.5)

Aphasia (f-t)

Aphasia (f-t)

Acoustic Phonetics (f-t)

Developmental Language Disabilities (f-t, with .5

teaching buy out)

Phonetics (f-t)

Linguistics (f-t)

Voice Disorders, Laryngectomy & Dysphagia (f-t)

Child Language Impairment (f-t) Maternity leave till

Jan 2011

Aphasia (f-t)

Developmental Psychology (f-t)

Developmental Communication Disabilities (0.6)

Research Methods/Psychology (f-t)

Psychology (f-t)

Phonetics (0.6)

Audiology (f-t)

Acoustic Phonetics (f-t)

Dysfluency (f-t)

Programme Support Unit Staff

Sarah Harvey

Bethan Lewis

Rakhee Rana

Programme Officer (ft)

Clinic/placement administration (0.6)

Senior Programme Officer (ft)

Academic Support Staff

Ali Quinn

Departmental Administrator 0.5

Technical Staff

Robert Davey

(f-t)

6

Research Staff

Anna Caute

Research Clinician (Aphasia) Maternity leave till Jan

2011

Speech Acoustics Lab assistant

Research Clinician (Aphasia) Covering Anna Caute till

January 2011

Research Assistant (Sign Language Studies)

Research Fellow (Sign Language Studies)

Research Fellow/Lecturer (Language Development)

Research Assistant (Child Language and Autism)

Research Assistant (Child Language)

Research Assistant (Sign Language Studies)

Research Associate (Child Language)

Research Assistant (Reading and Deafness)

Lead clinician for Aphasia Research Clinic

Bernie Coulthrust

Mickey Dean

Katie Mason

Wolfgang Mann

Chloe Marshall

Heather Payne

Jo Piper

Kate Rowley

Belinda Seeff-Gabriel

Zoe Shergold

Celia Woolf

Department PhD students

Valentina Arena

(Ushers Syndrome)

Anna Caute

(Aphasia) Staff Candidate

Liz Clark

(Early feeding in premature infants)

Ruth Deutsch

(Dynamic Assessment) (from Jan 2010)

Andrea Dohmen

(Child Language)

Celia Harding

(Non nutritive sucking in infants) Staff Candidate

Natalie Hasson

(Dynamic Assessment) Staff Candidate

Hannah Hockey

(Child Language)

Mariam Khater

(Language Impairment)

Abigail Levin

(Child Language) Staff Candidate

Anne Mayne

(Child Language)

Ghada Najmaldeen

(Child Language)

Sarah Northcott

(Aphasia)

Husen Owaida

(Child Language)

Kamila Polišenská

(Child Language)

Ashwag Wallan

(Child Language)

Anne Zimmer-Stahl

(Phonetics/Aphasia)

Staff Contact Details

Staff and PhD Students Telephone

Audiology Lab

3101

Room

D204

BOTTING Nicola

8314

D 222

Nicola.Botting.1@city.ac.uk

CAMILLERI, Bernard

8505

D227

Bernard.Camilleri.1@city.ac.uk

CAUTE, Anna

8202

DG21

Anna.Caute.1@city.ac.uk

CHIAT, Shula

8238

D 221

Shula.Chiat.1@city.ac.uk

COCKS, Naomi

8287

D227

Naomi.Cocks.1@city.ac.uk

7

E-mail Address

COULHURST, Bernie

0149

D212

B.Coulthrust@city.ac.uk

CRUICE, Madeline

8290

D225

M.Cruice@city.ac.uk

DAVEY, Robert

8216

D204

R.Davey@city.ac.uk

DEAN, Mickey

8202

D220

Michael.Dean.1@city.ac.uk

DIPPER, Lucy

4658

D207

L.T.Dipper@city.ac.uk

DODD, Barbara

3327

D218

Barbara.Dodd.1@city.ac.uk

HARDING, Celia

8946

D218

C.Harding@city.ac.uk

HARRISON, Kirsty

8292

DG21

Kirsty.Harrison.1@city.ac.uk

HASSON, Natalie

8280

D218

N.K.Hasson@city.ac.uk

HERMAN, Ros

8285

D227

R.C.Herman@city.ac.uk

HICKIN, Julie

8354

D222

Julie.Hickin.1@city.ac.uk

HILARI, Katerina

4660

D215

K.Hilari@city.ac.uk

HIRSON, Allen

8289

D209

A.Hirson@city.ac.uk

JOFFE, Victoria

4629

D224

V.Joffe@city.ac.uk

KNIGHT, Rachael Ann

8081

D204

R.Knight-1@city.ac.uk

LEE, Mary

8286

D215

M.T.Lee@city.ac.uk

LEVIN, Abigail

4662

D206

A.Levin-1@city.ac.uk

LEWIS, Bethan

8288

D217

B.Lewis@city.ac.uk

LITOSSELITI, Lia

8297

D207

L.Litosseliti@city.ac.uk

MANN, Wolfgang

8348

D220

Wolfgang.Mann.1@city.ac.uk

MARSHALL, Chloe

3633

D213

Chloe.Marshall.1@city.ac.uk

MARSHALL, Jane

4668

D223

J.Marshall@city.ac.uk

MORGAN, Gary

8291

D213

G.Morgan@city.ac.uk

MYERS, Lucy

8206

D206

L.Myers@city.ac.uk

D220

Jo.Piper.1@city.ac.uk

PIPER, Jo

PRING, Tim

8293

D210

T.R.Pring@city.ac.uk

QUINN; Ali

3922

DG21

Ali.Quinn.1@city.ac.uk

RANA, Rakhee

8281

D217

Rakhee.Rana.1@city.ac.uk

ROY, Penny

4656

D211

P.J.Roy@city.ac.uk

SAMOYLOVA, Katya

D204

Sign Lab

8979

D216

TURNER, Paul

3101

D204

Paul.Turner.1@city.ac.uk

VERHOEVEN, Jo

0148

D203

Johan.Verhoeven.1@city.ac.uk

WILLIAMS, Roberta

8295

D226

R.Williams@city.ac.uk

WOOLF, Celia

8296

D218

Celia.Woolf.1@city.ac.uk

Please note all Staff telephone numbers are can be searched on line at:

http://www.city.ac.uk/phone/

LCS FAX Numbers

FAX

LCS Admin Fax

LCS Forensic Fax

8

FAX Number

8577

8298

Room

D220

D212

Academic Year

Quick Reference Calendar 2010-2011

2010

September

October

November

December

2011

January

March

29th

Week of 4th

12th

Induction Day

Teaching starts

Programme Management Team (1pm)

10th

End of Autumn Term

Week of 17th Teaching starts

4th

Programme Management meeting (1pm)

April

June

11th

2nd

10th

Assessment Board

End of Spring Term

Programme Management Team (1pm)

July

September

30th

1st

16th

Submission of dissertation proposal

Assessment Board

Assessment Board

Departmental Information

Communications and how to find out what you need to know

There are numerous sources of information about what is going on in your

Department, in the School and in the University. It is your duty to keep yourself

informed about changes in teaching arrangements, study requirements,

assessment and so on. This Handbook explains quite a lot of what you need to

know and there is a great deal of information on the University, Departmental and

MSc webpages. Other sources of information which it is vital to use on a regular

basis include e-mail, notice boards, your student pigeonhole, and of course if need

be you can go to a member of staff, such as your Programme Director, Shula Chiat,

or ask at the Student Help Desk in D217, on the second floor of the Social Science

Building.

Pigeonholes

Student pigeonholes for your programme are currently located in D217, on the

second floor of the Social Science Building. If a tutor or another member of staff

needs to contact you, they may do so via your pigeonhole. It is therefore vital that

you look in your pigeonhole at least once per day when you are in the University.

9

E-mail

E-mail (electronic mail) is routinely used for communications with students and

should be checked regularly. All City students are encouraged to use the extensive

personal computing facilities that the University provides. Your student ID number

allows you to register as a computer user as soon as you complete your student

registration. Registration as a user will provide you with a guide to the e-mail system

and you can begin using it straightaway.

If you normally check e-mail on an address other than your university

address, please ensure that your university e-mail is forwarded automatically

to that address. The Department and University cannot accept requests for emails to be sent to addresses other than university addresses.

University website

Please check the website for central University, Departmental and course

information <www.city.ac.uk>

Finding a member of staff to help you

Sometimes you will have a question that cannot be answered by any of the

published sources of information. Members of the academic, administrative and

secretarial staff will do their best to provide the answer. Make sure you know the

location of your Departmental Office (D217). In most cases, you should first try

asking for help from your Departmental Office, your module tutor or the Programme

Director, though on occasions they will direct you elsewhere (e.g. to the School or

the Registry).

If you need to speak to a lecturer and can’t find them in their office, send an e-mail

and you should receive a response within two days (unless they are ‘out of office’).

Programme Director's office hours

The MSc Programme Director, Shula Chiat, will be available on Thursday

afternoons, 1.00-3.00, in her office (D221).

Contingency plans for staff illness

If a member of staff is unable to run an MSc module session, we will do our best to

give advance notice to all students attending the module, by setting up a 'telephone'

tree at the beginning of term to facilitate rapid communication. Depending on staff

and student availability, we will then either re-schedule the session, or make it

available on Moodle.

10

Organisation and Administration

Committee structure for School/Department governance

The governance of the university is the system by which key decisions about the

university are made. It is not vital to understand the role of every committee, but it

useful to know how key decisions which will affect your time at university are made,

and how you can influence them. A diagram showing the governance structure of

the University is provided in Appendix 4.

University

The University Council is the governing body of City University London; this means

that it is ultimately responsible for the affairs of the university. Council delegates all

academic matters to the Senate. This means that the Senate is the most important

committee for all academic issues. Students are represented on Council and Senate

by the Students’ Union.

Senate is also supported by a number of University-wide committees. The APPSC,

or Academic Practice Programmes & Standards Committee, advises Senate on all

issues relating to teaching, learning and the quality of programmes. The Student

Affairs Committee is the key committee at University level for all issues that directly

affect students.

School

At a school level the highest committee is the Board of Studies. This oversees the

establishment and effective operation of local policies concerning academic

practice, programmes of study, assessment and admission requirements for

programmes.

The Board of Studies is supported by a number of committees. The school-level

APPSC, or Academic Practice Programmes & Standards Committee, advises the

Board of Studies on all matters relating to programmes. The Student Affairs

Committee is the key committee for all issues that affect students. Senior student

representatives sit on the APPSC, and make up half of the SAC.

Department and Programme

At this level the key committee is the Programme Management Team. This

committee will consider all issues that affect the programme and give vital

information to other committees in the university. PMTs are often supported by

Student Affairs Committees, Programme Boards and Student-Staff Liaison

Committees. Student Representatives sit on all of these committees.

MSc Human Communication Programme Management Team

The MSc Human Communication Programme Management Team normally meets

once in each term. The PMT consists of the Programme Director, all academic staff

11

involved in the programme, and student representatives. The Chair of the PMT for

your course is Programme Director Shula Chiat.

Student representatives, who are elected by students on the course, are

responsible for raising matters of concern to the student body at meetings and for

reporting back on the discussion and any decisions taken.

Student Representation in School of Community & Health Sciences

The School of Community and Health Sciences is committed to student

representation. The system of student representation works on two levels, with

programme level student representatives and senior student representatives at

school level.

Programme Level

For each programme, at least one student should be elected for each cohort. This

student will represent the views of all students in their cohort to staff and academics,

and will sit on the Programme Management Team, which allows students to raise

issues directly related to programmes and modules.

School Level

Each department then selects two senior student reps. These students are the key

representative for their department and form the basis of the School’s Student

Affairs Committee. The Student Affairs Committee, which reports to the Academic

Practice, Programmes and Standards Committee, is the key committee for the

student experience throughout the School, and monitors the responsiveness of

departments and student services to all forms of student feedback. The Student

Affairs Committee maintains an issue tracker to ensure that the School responds

effectively to feedback in a timely fashion. The committee is student-driven and will

be co-chaired by a student. The Student Affairs Committee works with and

complements student representation on a programme level.

This system fits neatly with the student representation system of the main university,

and will give School students a clear voice throughout the school and university.

Expressing your views

The main mechanism for airing and dealing with student issues and problems is

through your student representative on the MSc Human Communication

Programme Management Team, but you can also:

ask your representatives on the Student Affairs Committee (see previous section)

to raise any issue relating to students;

make your own views known to, or seek information from, your student

representatives on the Student Affairs Committee when there is any matter under

consideration which may involve student interests.

At an individual level, you are free to bring any matter to the attention of your

module leader or Programme Director in the first instance. If you are still unhappy,

12

you can approach the Head of Department or Dean and they will take appropriate

follow-up action, such as reference to the relevant Departmental, School or

University committee.

Student evaluation of teaching

Student feedback is collected near or at the end of each module, through an

anonymous questionnaire which will either be distributed at the end of a lecture or

posted on Moodle under that module. This is available to all students registered for

the module.

A statistical summary of responses to the closed items on each questionnaire is

prepared and is available to the Dean, Head of Department, and Programme

Management Team. Analysis of the feedback and report on follow-up actions are

part of the Annual Programme Review which is presented to the Programme

Management Team before submission to the Academic Practice Programmes &

Standards Committee (APPSC – see above).

In addition, an opportunity for informal feedback is given by module leaders in the

course of each module. Programme Management Teams also give student

representatives the opportunity to give feedback on all aspects of the course on

behalf of their fellow students.

University Complaints Procedure

Students who wish to make a complaint against the University concerning the

quality of an academic programme or any related service should do so at the local

level, with the individual, department or service provider concerned. Students may

individually or collectively raise matters of proper concern without prejudicial effect.

If you decide to make a complaint, your privacy and confidentiality will be respected,

although complaint resolution may not be possible without revealing your identity to

the subject of the complaint. Anonymous complaints will not be investigated. You

will receive fair treatment provided that complaints are not made maliciously.

Decisions made by the University will have regard to any applicable law. You are

entitled to be accompanied at all stages of the complaints procedure by a person of

your choosing. If a legal representative is chosen, you must give the University prior

notice in order that it may consider similar support. Details of how to make a

complaint can be found on the web http://www.city.ac.uk/ace/complaints.html

Student Support

Library Information Services

The main University Library is in Northampton Square occupying the top five floors

in the University Building. As well as the main library, there are more specialist site

libraries at Frobisher Crescent (business and arts policy) and at West Smithfield

and Whitechapel (nursing and midwifery). All students are welcome to use any

library. There are 905 study places of which most are in the main library.

13

Postgraduates may borrow up to 15 books. Books are available for seven day loan

and three day loan. A few may be available for up to three weeks. Books that are in

high demand are available on a 24 hour short loan basis and there is also a

reference section. Although copies of standard texts and required reading are

available in the Library, you will need to buy those books that you use regularly.

Details of both the Library book stock and periodicals holdings are held on the

University network, which can be accessed from any point in the University and via

the web, as well as in each of the libraries. There is also easy access via the local

and national academic networks to catalogues in many other academic libraries.

The Periodicals Collection, in conjunction with electronic journals and databases,

supports all types of postgraduate work from course assignments to doctoral

dissertations.

The Library also provides access to a growing number of electronic information

services and items not held in the Library may be obtained from elsewhere via the

Inter-Library Loans service.

Further information about the University’s Library Information Services can

be obtained via their web site: <www.city.ac.uk/library>

14

IT Public Services

Who looks after your IT Services?

Whenever you use a lab PC, borrow a book, use the Moodle, send an email or use

the Halls of Residents network you will be dealing with the services provided by

Information Services who underpin and support your IT experience at City

University.

How do I use the computers in the public computer labs?

You need to log in using your computing account username e.g. abcd123 and

password. You will receive these during registration as part of the IT account

activation process.

If you are unsure as to whether you have activated your IT account please visit the

IS Service Centre (E101) at Northampton Square (or your local support centre at

the other sites) where staff will be able to advise you.

Is there any service downtime I should know about?

In addition to the Scheduled Maintenance Period (normally undertaken on

Tuesday mornings between 8am and 10am GMT/BST).

Please check the Message of the Day by calling 0207 040 8181 and selecting

Option 4 for announcements and information about any scheduled server downtime

or technical issues.

Who can I contact for more help?

IT RESPONSE CENTRE

For technical problems, account queries or other IT related issues, contact the IT

Response Centre by e-mail: response-centre@city.ac.uk, or call 0207 040 8181.

IS SERVICE CENTRE

For face-to-face support with any IT related query, software/hardware requests or IT

advisory services, please visit the IS Support Centre in E101 (Drysdale Building –

Northampton Square).

15

Frequently Asked Questions

Q. I know my username and password, but the computer reports that my

computing account is locked and I need to see an administrator.

A1. When logging into your account, you have three attempts to do so successfully

after which your account will be locked out. When this occurs, wait for 10 minutes

before trying again.

A2. Please ensure that no fees are outstanding and that you have not been barred

by the Finance Department (www.city.ac.uk/finance or 0207 040 3026)

Q. How do I change my computing account password?

A1. If you have forgotten your password visit the IS Service Centre (E101) at

Northampton Square (or your local support centre at other sites) with your valid ID

card and we will change it for you.

A2. If you know your password but would like to change it:

Please visit http://www.city.ac.uk/changepassword or from any Information

Services public computer room which has MS Windows go to Start - Programs Useful Utilities and click on Change Password and again follow the instructions.

Q. Where can I top up my print credit?

A. You can top up your print credit at the IS Service Centre at Northampton Square

(E101) or at the library with your debit card. For other sites, you can pay at your

local support centre. Please contact Cass Student IT Helpdesk at Bunhill Row for

information on printing there: cass-helpdesk@city.ac.uk

Q. How much storage space do I have on the network?

A. Each user is allocated a disk quota – a limit on the amount of space that you can

use. The quota for Windows XP system is 200MB and LINUX system is 50MB.

Users must begin housekeeping – i.e. deleting or compressing your work or copying

it to another location – from the start of account usage. It is not possible to increase

your storage allocation except in special circumstances where more space might be

required, for a project for example. In these instances space requirements are

assessed on a case-by-case basis.

Q. What is Extended Hours Service?

A. Extended Hours Services are three rooms at the Northampton Square site which

can be accessed out of normal opening hours. To gain access to any of these

rooms during extended hours you will need to register your University card with a

PIN. You can do this at the machine by the Student Centre at Northampton Square.

You just have to follow the on screen instructions.

Q. When does my account expire / why can’t I keep it indefinitely?

A. Your account will usually become inactive one month from the end of your

course and is automatically deleted 30 days after this. Due to storage limitations

and administration overheads it is not usually possible to keep your account and email active for any longer than the stated two months.

Q. Can I put my own paper in the printers?

16

A. Unfortunately it is not possible to put anything other than the University-supplied

paper in the printers. This is due to the potential risk of invalidating warranty and

service agreements.

Q. I’ve sent a job to print, it says ‘Sent to printer’ but nothing has come out?

A1. Check your print credit to make sure the credit is enough to print all the pages

you require otherwise the print server will discard the entire job.

A2. Check the document itself is set to the correct paper size.

Q. I’m in a lab at Northampton Square - where is the colour printer located and

what is it called?

A1. For A4 sized prints send your print job to service-centre-colour-A4, print cost

is 20p per sheet.

A2. For A3 sized prints send your print job to service-centre-b&w-a3, print cost is

20p per sheet for Black & White and £1 for Colour.

The printer is located in the IS Service Centre (E101) at Northampton Square.

Q. Can I install some software?

A. Strictly no software is to be installed without permission from Information

Services; you will be barred from using your account if found doing so.

Q. I printed something and don’t know where it has been printed out?

A. Go to File, then Print and see what the default printer is set to. You should

normally find your print-out at the local printer in the room where you are working.

Q. When I log in it takes a long time – can I get help?

A. If you are at Northampton Square, pay a visit to the IS Service Centre in E101 (or

your local support centre at other sites). The advisor will be able to investigate and

perhaps reset your profile.

This guidance note is produced by Information Services and Libraries and is

available on the ISL website: www.city.ac.uk/isl.

Also see related guidance notes on Moodle and Library services.

The Public Access IT Facilities

Our aim is to deliver a centrally managed, reliable and excellent quality IT service to

both staff and students, which complements the facilities provided by individual

departments.

The services we provide include the University email system, web servers, backup

and media storage, as well as a University wide local area network (LAN). An

Internet connection is supplied via JANET (Joint Academic Network).

There are over 1500 Windows and 46 Linux public access workstations available for

use across the University. A user account is required to gain access to these.

During term time these are heavily used during the day, especially at assignment

time, so you should plan your work accordingly.

17

Some workstation rooms can be booked for classes and as such may be

unavailable for long periods during the day and evening. These rooms should have

timetables posted on the door indicating booked/available periods.

‘At-Risk’ period

All centrally managed systems are designated as “at-risk” between 8am and 10am

every Tuesday, when essential maintenance work is carried out. This may result in

systems not being operational during this time. Information on service disruptions

can be obtained by calling 0207 040 8181 and choosing option 4.

The IT User Account

Consists of a username and password.

Is obtained via the Self-Registration process, which can be completed on a

Public Access workstation. Instructions can be picked up from your local

Support Centre; alternatively this can be done from home by visiting

http://www.city.ac.uk/itactivate and following the on screen instructions.

Provides access to the systems, applications, the Internet, your University email

account, your personal web space and also to your personal networked file

storage.

Choosing your password

Passwords must be 6, 7 or 8 characters long and must contain 1 digit and 1

UPPERCASE letter.

Changing your password

You can change your password yourself by visiting

http://www.city.ac.uk/changepassword or

o On the Windows system by going to Start, Programs, 3.Useful Utilities,

Change Password.

o On the Linux system by Telnetting to unix.city.ac.uk and using the change

password option.

If you forget your password you can visit your local support centre for assistance –

make sure you have your valid City ID card with you.

Saving files on networked file servers

You can save files on your allocated network space from both the Windows and

Linux workstations.

On the Linux system:

Save your files in your home directory area. This space is limited to 50Mb and

also includes your personal web space.

On the Windows system:

18

Save your files to your U:\ (MyDocs) drive. This space is currently limited to

200Mb.

NOTE: All systems give problems occasionally so it is advisable to keep copies of

important files on other media, such as USB pens or CD/DVD.

Extended hours service – *24 hours a day, 7 days a week

Located on the Northampton Square site on Spencer Street, there are three rooms

(EG05, EG03, EG04) which are open constantly (except during the Christmas

vacation). At times these rooms will be closed for maintenance; these times will be

clearly advertised. To access these rooms outside of normal opening hours you will

need to register your ID card with a PIN number for the out-of-hours access door.

To do this please visit the 24 hr PIN kiosk by the Student Centre and follow the on

screen instructions.

Scanners

These are available on the Northampton Square (NSQ) site. Located in the IS

Service Centre (room E101), due to demand it is advisable to call ahead and check

before making a special trip in to use them. They are allocated on a first come first

served basis.

Note: There may be legal restrictions on the amount of copyrighted information that

you can scan. For more information visit:

http://www.city.ac.uk/library/using/copyright.html

Printing

Credit can be purchased from all campus library service desks, or IT Support

Centres. Costs per sheet may vary between sites; refer to local support for

information.

All printouts are sent to a shared laser printer in the room you are working in,

unless you choose to send it to another printer.

A3 and A4 colour printing is available through the Service Centre

A4 Acetates can also be printed through the Service Centre

19

Note:

Printers are named based on their location, for example “ps-eg14” is a printer

located in room EG14

You cannot use your own paper/acetates in any centrally managed printer.

Using your own laptop on the wireless network

You can use your own laptop to gain access to the CityWifi wireless service.

Instructions on connecting can be obtained from the IS Service Centre at

Northampton Square, the Library or your local support office at other sites.

Once the computer is configured it should be able to connect to the Internet from

most locations throughout the University. Please check with your local support office

for full coverage details.

Support/Service Centre

Face to face/walk-in support is available via the IS Service Centre

o Located in room E101, Drysdale Building in Northampton Square

o Opening hours 8am-8pm (term-time), 8am-5pm (vacation time)

o Contact by phone on 0207 040 8181 or email via responsecentre@city.ac.uk

20

Support is primarily for students with issues relating to PCs in the public

workstation rooms.

You can also obtain support with configuring and troubleshooting problems

connecting to the University’s wireless service.

University Staff members will be able to receive assistance with setting up role

accounts, staff accounts and any other support queries relating to University IT

systems and services.

Students will be able to credit their printing account and get support with printing

problems.

Buy basic consumables such as CD’s, USB memory sticks or Digital Video

tapes for the loan Camcorders.

Support for the network in Halls of Residence, including troubleshooting

connection issues and advice on virus infections.

Public Access Workstation Rooms - Locations

(* denotes site location)

Room

*Northampton Square

College Building (A)

A217

A218

A220

A308

A307

Drysdale Building (E)

EG14 (unbookable)

EG13

EG12

EG07

EG05

EG03

EG04

IS Service Centre

Tait Building (C)

C218

C301

University Building

B309(Room A)

Library Level 2

Library Level 3

*Bunhill Row (CASS)

Cass IT Support

1001, 1002, 2000

2001

*West Smithfield

5th Floor

*Whitechapel

1st Floor

21

Term time opening

Windows

8am – 8pm

Linux

25

25

30

32

16

8.30am – 8.30pm

78

34

41

40

24 hour access area

8am – 8pm (during term

time)

21

10

20

*available for all support

queries

8am-8pm

6

30

9:00-20:30 Mon-Fri

9.30am -8pm (7pm

Fridays) (Sat 12:00-17:00)

29

40

64

9am-6pm (Mon-Fri)

8 am – 9.30pm

Teaching only

8.30am – 8.30pm

55

8.30am – 7.30pm

28

Audio Visual Services

Audio Visual provide equipment and technical support for all University members.

Their technicians offer assistance and advice in setting up and using all classroom

teaching equipment.

Classroom Facilities

The classroom podium, or Pod for short, is a purpose-built unit that houses various

lecture room technology at City University. The Pod offers you convenience and

flexibility: everything you need to start your meeting or lecture is at your fingertips

and all the technology is supported and maintained by the Audio Visual (AV) team.

Each classroom Pod comprises:

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

A networked Windows PC (based on the current student build)

A DVD/VHS player

An audio cassette deck

A Visualiser (document image camera)

A Sympodium (a touch screen / interactive pen display)

Video/audio/network cables for a laptop connection

A Crestron touch-control panel which allows you to switch between the

components of the Pod (Resident PC, Laptop, Visualiser, DVD, VHS and Audio

tape).

The visual output from each Pod is normally displayed via data projector onto a

screen, or in some rooms it is output onto a large plasma TV. All pods are also

connected to wall mounted speakers.

Equipment Loans

AV loans equipment to City University students and staff. Equipment can be

borrowed free of charge.

Available equipment:

o Camcorders: 10 x Digital Video Cameras with tripods

o MP3 Recorders: 5 x Zoom MP3 recorders with memory cards.

o Microphones: 8 x Microphones, 3 Lapel microphones

22

To borrow equipment, students must complete an equipment loan form, which

must be signed by a member of staff from their department and returned to the

Response Centre office, room EG02.

Booking forms are available from the Service Centre.

Portable loan equipment should be collected from EG02 and returned

immediately after use (note, late returns are subject to fines).

Users are responsible for security of equipment on loan.

We will require five days’ notice to book equipment.

Educational Advice and Guidance Service

The Educational Advice and Guidance Service provides support for all students and

can help with study skills, including how to learn more effectively, charting progress,

making the most of feedback from tutors and making decisions about future learning

needs.

The service is based on equal opportunity principles and delivered by suitably

trained and experienced staff who will refer students appropriately if they cannot

meet their needs.

Contact Number: ext 8771

University’s Policy on Student Support

The University has an agreed Student Support Strategy, which aims to provide a

clear plan for the overall organisation, management, development and resourcing of

the various services which support the University’s students in achieving their goals.

The Strategy is overseen by the University’s Student and Staff Services

Development Group (SSSDG), which includes student members. We hope that you

find it useful.

Personal Tutors

It is important from the point of view of your welfare as a student and individual that,

during your time at University, there is a member of staff who gets to know you,

whom you get to know, and who will give you guidance and support in academic

matters and on a personal level. In your case, the Programme Director (Shula

Chiat) will be your first point of contact and will play this personal tutoring role.

However, if issues arise which you would prefer to discuss with an independent

person, the Programme Director will identify a separate personal tutor for you.

Remember, it is your responsibility to get in touch with your Programme Director (or

personal tutor) whenever you have any problems and to keep them informed of any

changes in your circumstances. One of their functions is to inform Boards of

Examiners, Appeal panels and so forth, of any circumstances that may have

affected your performance. Furthermore, they will serve as a link with other

resources within and without the University, directing or referring you to appropriate

services if the need arises. They may also provide references for you at the end of

the programme.

To sum up: If you are in any difficulty whatsoever, academic or personal, please

discuss it with your Programme Director, or tell them that you would like to be

allocated an independent personal tutor to discuss such matters.

Other sources of support

In addition to support from your personal tutor, department and/or school, the

following services are provided by the University to support you during your studies.

23

Student Centre

Level 2, Refectory Building (Main University Building at Northampton Square)

Tel.: 020 7040 7040

Fax: 020 7040 6030

The Student Centre is able to advise you on any query you have whilst you are a

student at the City University.

The new Centre brings together a comprehensive range of support activities which

are easily accessible to all City University students.

The Centre will be a point of contact for information about the following areas:

Academic issues

Dyslexia

Disability

Employment

E-learning

Faith

Financial support

Health

Housing

International student support

Learning support and study skills

Library and computing

Payment of fees

Purchase of student cards and photocopy cards

Student appeals and complaints

Please see the website www.city.ac.uk for further information.

Students’ Union

The Students’ Union Welfare and Education Advisory Service employs

professional advice workers who can be consulted on a wide range of topics

including finances, grants and benefits, accommodation, health and safety matters,

and issues relevant to overseas students and other minority groups.

Further information on how to contact these services can be found on:

www.cusuonline.org

24

Centre for Careers & Skills Development

The University Centre for Career & Skills Development (CCSD) provides a service

to current full-time and part-time undergraduates and postgraduates and to recent

graduates of the University. Our aim is to give you the advice, information and skills

you need to make a smooth transition into the world of work.

Students can use the wide selection of careers resources at any time during

opening hours, call in for a brief chat with a Careers Adviser over the lunch-time

period, or book a longer appointment if needed. Careers Advisers also run regular

workshops on a range of job search related topics and may run specific sessions

within the School. For full details, please visit our website –

http://www.city.ac.uk/careers

The CCSD also runs the Vacancy Board service which can help you find casual

work while you are studying and it also advertises a wide range of graduate

vacancies. Opportunities for volunteering and mentoring can also be arranged

through the service.

The Careers Centre is located in Northampton Square, Tel: 020 7040 8093.

Programme

Please note that you can view the full Specification for your programme on the

University’s Programme Information and Specification Management (PRISM)

system, accessible at: http://was.city.ac.uk/External_Reports/ExternRepFront.jsp

Background

The Department has been providing education to speech and language therapists for

over fifty years, initially in the School for the Study of Disorders in Human

Communication and from 1982-1999 as the Department of Clinical Communication

Studies within City University. In 1999, the Department changed its name to

Language and Communication Science, in order to better represent the current range

of activities including Deaf Studies. Over 100 therapists graduate from the

Department every year, making it one of the largest centres of education for the

profession in the country. The Department’s extensive and expanding research and

applied activities provide valuable resources, supporting teaching that combines

academic excellence and innovative theoretical work with a practical focus. As part

of the School of Community and Health Sciences, the Department is also able to

draw on the strengths of a range of other departments involved in health-related

education and there are links with departments such as Psychology and Sociology.

The Department has a long-standing commitment to postgraduate education for

qualified speech and language therapists, instituting the UK’s first MSc degree in the

discipline. To keep pace with current developments we have developed the present

MSc programme, which is designed to be both academically rigorous and clinically

relevant. The modular nature of the MSc course enables students to tailor their

studies to meet their interests and professional development needs.

25

26

Aims and Objectives of the Programme

Aims

To provide a flexible, professionally-orientated MSc programme for Speech and

Language Therapists and others with a specific interest in the field of

communication and communication disorders.

To foster applied and theoretical expertise in the areas of speech, language,

and communication.

To develop students' research skills.

To provide students with opportunities to design their own course by selecting

from available modules.

To provide input from a wide range of experts in the fields of both theory and

practice.

To provide students with a recognised qualification indicating the level of

specialised expertise.

Overall learning objectives and outcomes

At the end of the course students will be able to:

synthesise and critically evaluate relevant research literature.

critically appraise and integrate different perspectives and theories within each

module and across modules.

demonstrate in-depth knowledge and understanding of current perspectives,

theoretical concepts, research methodologies and research findings in their

areas of study.

demonstrate knowledge and understanding of the principles of research design

and statistics.

consider and evaluate the implications of current research for

clinical/educational/social policy and practice.

engage in independent study using a range of research resources.

demonstrate written and verbal communication skills appropriate to Master’s

level.

show insight into and respect for the experience of service users and

participants in research.

Programme Organisation

The MSc programme comprises 8 taught modules of 15 credits plus a dissertation

module of 60 credits. Successful completion of all 9 modules (180 credits) leads to

the award of the MSc in Human Communication.

The taught modules can be taken on a part-time (one day a week) basis over two

years, or can be completed on a full-time basis over one year. It is anticipated that

clinically employed students will attend on a part-time basis, completing the taught

MSc programme in two years. Students can take the programme on an occasional

basis, i.e. by taking separate modules as convenient.

27

The dissertation is normally completed within one academic year after the

completion of the 8 taught modules.

Structure of the MSc

The compulsory modules of the MSc are:

Research Design and Statistics A

Research Design and Statistics B

UK Therapists on the MSc programme are encouraged to take:

Evidence-Based Practice

Clinical Management

Identity, Inclusion and Living with Disability.

All MSc students must additionally complete the research dissertation.

Diploma

Completion of 8 taught modules (120 credits) without the dissertation leads to the

award of the Diploma.

Individual Modules

Students can take modules on an individual basis, by agreement with the Module

Leaders. Successful completion of each module leads to the award of a Certificate

of Credit. Module outlines are provided at the end of this section.

28

Induction

Before the start of the Autumn Term, all new students are required to attend the

induction day on 29th September 2010:

10.00 – 12.00

Welcome and Registration

AG01

(for students who have not registered by post)

12.00 – 13.00

Introduction

(Shula Chiat and Vicky Joffe)

13.00 – 14.00

Lunch and Meeting with LCS Staff Members

(with information about Student Representation

and Student Experience)

14.00 – 15.00

Library and E-learning Induction

(Steve O’Driscoll)

Library Teaching

Room (far end of

Level 3 of Library)

Additional activities

As well as the induction day, there will be supplementary activities for all Human

Communication students. Students attending on Thursdays will be expected to

attend departmental research seminars held on those days. All students are

expected to be conversant with or attend training courses offered by the university in

such areas as internet database searching, e-mail, web design. Three optional

sessions on Information and IT are included in your programme:

Monday 25th October, 2.00-4.00: Introduction to Databases – Library IT Suite

Monday 1st November, 2.00-4.00: Evidence Based Practice – Library IT Suite

Monday 22nd November, 2.00-4.00: RefWorks – Library IT Suite

Full details of other courses may be found on the university website.

.

29

MSc Human Communication Timetable: 2010-11

Note:

If fewer than 3 students select a particular module, that module may not run, in

which case the student(s) who selected it may have to choose an alternative

module.

Please check the final timetable, with exact timing of sessions and confirmation

of rooms, which will be distributed at induction.

Autumn Term: Weeks beginning 4 October - 6 December 2010

Morning

Thursday

Friday

Afternoon

10.00-1.00

1.30-4.00

HCM002

HCM009

Clinical Management

Habilitative Audiology

D106

D107

10.00-12.30

1.30-3.30

HCM012

HCM007

Research Design and Statistics A

Dysphagia and Disorders of Eating and

Drinking

Level 3A

D112

Except:

8th October and 5th November

C135

HCM010

Identity, Inclusion and Living with Disability

This will run on four full days:

Tues 2nd November

Weds 3rd November

Tues 9th November

Weds 10th November

10.00-1.00

2.00-5.00

10.00-1.00

2.00-5.00

10.00-1.00

2.00-5.00

10.00-1.00

2.00-5.00

D107

D107

D106

C164

C357

C357

C357

C357

Optional Workshops on Information and IT

Monday 25th October, 2.00-4.00: Introduction to Databases – Library IT Suite

Monday 1st November, 2.00-4.00: Evidence Based Practice – Library IT Suite

Monday 22nd November, 2.00-4.00: RefWorks – Library IT Suite

30

Spring Term: Weeks beginning 24 January – 28 March 2011

Morning

Monday

Afternoon

10.00-1.00

HCM021

Case-Based

Clinical

Management

D108

Thursday

Friday

10.00-1.00

10.00-1.00

2.00-4.00

HCM003

HCM016

HCM008

Cognitive

Communication

Impairments

Speech Acoustics

& Speech

Perception

Evidence-Based

Practice

D106

D107

C220

10.00-1.00

2.00-5.00

2.00-5.00

HCM020

HCM001

HCM005

Research Design

and Statistics B

Acquired

Language

Impairment

Developmental

Language

Impairment

D112

D113

Level 3A

Project session: 10.00-13.00, Wednesday 2nd March 2011

HCM019

Language Learning and Development

This will run on three full days: Weds 19th January

Thurs 20th January

Weds 30th March

9.30-1.00

2.00-5.00

10.00-1.00

2.00-5.00

10.00-1.00

2.00-5.00

CG56

D113

D106

C313

D112

D106

MSc Human Communication Provisional Timetable: 2011-12

We expect the timetable to be the same as for 2010-11, but this may be subject to

change due to staff and/or student availability and student module choices. We will

give you as much notice as possible if any changes are required.

31

Module Outlines: MSc in Human Communication

32

HCM001 Acquired Language Impairment Module

Module Leader: Julie Hickin

Module rationale

This module will provide you with updated knowledge of new developments in

language processing theory and to encourage you to consider how to integrate

language work with social model approaches to aphasia therapy innovatively and

creatively.

Module aims

This module aims to update your theoretical understanding of aphasia and help you

apply that knowledge to clinical practice. It aims to encourage the integration of

language processing theory with social approaches to aphasia. It will explore specific

issues in aphasia, such as conversation and non verbal modalities, and specific

manifestations such as jargon aphasia. It will promote clinical and reflective thinking,

both with respect to the literature and clinical practice.

Indicative content

You will cover the following topics:

Levels of processing - single word models

Connectionist models

Semantic impairments

Sentence processing and 'thinking for speaking'

Conversation Analysis, conversational therapy approaches and outcome

measurement

Integrating the Social Model with language processing work

Quality of Life issues

Jargon aphasia - theoretical models and clinical applications

Bilingual aphasia - theoretical models and clinical applications

Implementing and analysing therapy

Module learning outcomes

On successful completion of this module, you will be expected to be able to:

Knowledge and understanding

Demonstrate an understanding of lexical and sentence processing models and

their application to the assessment and treatment of aphasia.

Demonstrate an understanding of how to assess and remediate conversational

skills in aphasia.

33

Demonstrate an in-depth understanding of the process of therapy and its

evaluation.

Demonstrate understanding of nonverbal modalities in aphasia and their

remediation.

Demonstrate an understanding of issues related to quality of life in aphasia.

Demonstrate understanding of specific manifestations of aphasia, such as

bilingual aphasia and jargon aphasia.

Skills

Engage confidently in academic and professional communication, reporting on the

intended remediation plans clearly and competently.

Demonstrate self-direction and originality in planning a remediation programme,

drawing on the ideas presented in this module.

Demonstrate an ability to think critically about research literature, synthesise

relevant research from a range of sources and apply this to clinical practice.

Integrate language processing and social model ideas in a clinically useful way.

Module learning and teaching methods

Methods will include seminars, workshops, and critical reading groups.

Assessment methods

You will be assessed through an oral presentation (50%) and literature review (50%)

to assess your understanding of relevant language processing methodologies and

your ability to integrate these with social model ideas, using recent research

publications.

In addition, the oral presentation will assess your self-direction and originality in

planning a remediation programme and your ability to engage in verbal

communication, and the literature Review will assess your written communication.

Pass requirements

In order to pass the module and acquire the associated credit, a student must

complete the assessment component and achieve an aggregate Module Mark of

50%.

The Module Mark shall be calculated from the Literature review weighted at 50.0%

with a minimum mark of 50% and Oral presentation weighted at 50.0% with a

minimum mark of 50%.

Indicative reading list

Basso, A. (2003) Aphasia and its Therapy. New York. OUP

34

Basso, A., Cappa, S. and Gainotti, G. (2000) Cognitive Neuropsychology and

Language Rehabilitation: A Special Issue of Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. Hove.

Psychology Press.

Byng, S., Swinburn,K. and Pound, C. (1999) The Aphasia Therapy File. Hove

Psychology Press. (Paperback published 2001).

Byng, S., Duchan, J. and Pound, C. (2006) The Aphasia Therapy File: Volume 2.

Psychology Press.

Chapey, R. (2008) Language Intervention Strategies in Aphasia and Related

Neurogenic Communication Disorders. Philadelphia. Lipincott, Williams and Wilkins.

Chiat, S., Dipper, L.T. & McKiernan, A. (2001) Re-dressing the balance: A

commentary on Duchan's Clinical Practices Re-examined. Advances in Speech

Language Pathology. Clinical Forum.

Duchan, J.F. (2001) Impairment and Social Views of Speech Language Pathology:

Clinical Practices re-examined. Advances in Speech Language Pathology. Clinical

Forum.

Hillis, A. (2002) The Handbook of Adult Language Disorders: Integrating Cognitive

Neuropsychology, Neurology and Rehabilitation. Psychology press.

Howard, D. & Hatfield, F.M. (1987) Aphasia Therapy: Historical and Contemporary

Issues. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Jordan, L. and Kaiser, W. (1996) Aphasia: A Social Approach. London. Chapman

Hall.

Law, J., Chiat, S. & Marshall, J. (1997) Language Processing in Children and Adults.

Whurr Publishers.

Lesser, R. and Perkins, L. (1999) Cognitive neuropsychology and conversation

analysis in aphasia : an introductory casebook. London: Whurr.

Martin,N., Thompson,C. and Worrall, L. (2008) Aphasia rehabilitation : the impairment

and its consequences. San Diego. Plural Publishers.

Nadeau, S. and Ganzalez-Rothi, L. (2000) Aphasia and Language Theory to Practice.

New York. Guilford.

Parr, S., Byng, S. and Gilpin, S. (1997) Talking about Aphasia.OUP.

Parr, S., Duchan, J. and Pound, C. (2003) Aphasia Inside Out: Reflections on

Communication Disability. OUP.

Pound, C., Parr, S., Lindsay, J. and Woolf, C. (2000)Beyond Aphasia: Therapies for

living with communication disabilities. Bicester. Speechmark.

Rapp, B. (2001) The Handbook of Cognitive Neuropsychology: What deficits reveal

about the human mind. Psychology Press.

Whitworth, A., Webster, J. and Howard, D. (2005) A Cognitive Neuropsychological

Approach to Assessment and Intervention in Aphasia. Psychology Press.

35

HCM021 Case-Based Clinical Application Module

Module Leader: Mary T. Lee

Module Tutors: Mary T. Lee, guest lecturers TBA

Module rationale

This module aims to provide you with advanced clinical experience through case

based learning focusing on clinical areas not addressed in other modules. You,

through your choice of client, will become familiar with the body of literature driving

clinical practice in a specific area.

Module aims

You will apply evidence from the literature in clinical decision making using a

range of client groups and presenting conditions.

You will apply advanced clinical decision-making in diagnosis and design of

intervention.

You will apply clinical knowledge and understanding to establish appropriate

intervention using conceptual frameworks and the cycle of intervention.

You will identify and develop use of advanced technical skills associated with

different approaches and patterns of SLT delivery.

Indicative content

You will concentrate on one of the following clinical areas throughout the course as

an exemplar case:

Voice / ENT

Hearing Impairment

Autism

Cerebral Palsy

Working with the chosen case you will assess, diagnose, design a treatment

programme, and provide rationale for intervention. The final case choice will be based

on majority preference as there must be a critical mass of 4-5 of you working on any

one case.

Module learning outcomes

On successful completion of this module, you will be expected to be able to:

Knowledge and understanding

Demonstrate a comprehensive understanding of the clinical area in which you are

working.

36

Understand the factors that influence effective clinical case management with

analysis of factors both within the immediate client team as well as the wider client

environment.

Understand the principles and information of clinical case management.

Skills

Critically evaluate and synthesise relevent research from a range of sources.

Demonstrate a level of conceptual awareness that allows for selection and use of

appropriate techniques of evaluation and analysis of data with minimum guidance

using the recommended frameworks and methods with critical awareness.

Interact effectively within a team/learning group as member contributing ideas,

receiving information, modifying responses and collaborating with others in pursuit

of a common goal.

Demonstrate independent learning ability in order to identify key areas to address

and to choose appropriate tools/methods for resolution.

Present information in a variety of formats appropriate to the stated goal and

target audience in a confident and professional way.

Demonstrate self-direction and autonomy in identifying key elements of problems

and choose appropriate methods for their resolution in a considered manner.

Module learning and teaching methods

This module comprises three lecturer-led sessions for information and discussion.

The remaining sessions will be you working in your group to address the

management of your client. You will be expected to work independently within the

group, to chair the sessions, establish goals and assign roles to other group members

for the purposes of information gathering and decision making regarding

management of the client.