Kirkpatrick on Baptism in the KJB

advertisement

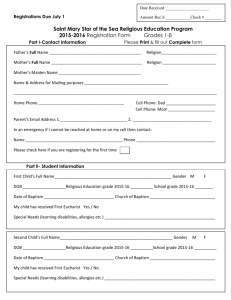

BAPTISM IN THE KING JAMES VERSION By Paul Kirkpatrick (Compelling Proof That "Baptism" Is Translated Correctly In The King James Bible) The Problem Stated In the course of examining the question as to why some groups use modes other than immersion for their baptism, one will occasionally come across the charge that is leveled by some people, Baptists in particular, that one reason for the existence of these variations in the mode of baptism is that the English word "baptism" and its cognate verb form "to baptize," which are found in the King James Version of the Bible, are extremely vague in their meanings. Should one ask of these same people their explanation of why the King James version's translators chose to use such words as these, rather than "immersion" and "to immerse," many of these people will offer in reply something on the order of the following line of reasoning: The translators (as well as King James I himself) were members of the Church of England (Anglican or Episcopalian Church) which uses sprinkling for their baptism. Because of this, when the translators come to the Greek words for this ordinance, which, implicit in their literal definitions, preclude anything else but immersion, they had to do something to conceal the true meaning of these words. To use "immersion" and "to immerse" would expose their erroneous practice. In order to accomplish this and to becloud the issue of the proper mode, they decided not to translate those Greek words. Rather, they transliterated the Greek letters of these words into Roman alphabet, thus coining a new set of English words - - "baptism" and "to baptize."(1) While such logic as this may make good material for exposing some aspect of Protestant deceitfulness, is such a charge as this an accurate one? Are the translators of the King James Version guilty of "taking away form the Word of God?" Moreover, if they mishandled this very important aspect of baptism, who is to say that they may have not also misrepresented other essential Christian doctrines and practices? Some Preliminary Considerations The purpose of this work is to examine the above viewpoint from three disciplines that are essential to determining its validity: (1) The etymology of these words, i.e., the study of their origin. (2) The history of the mode of baptism that was used in England up to the time that the King James Version was produced. (3) In conjunction with 1 and 2, an examination into the semantics of these words as they applied to the translators will also be taken into consideration. This work will deal with baptism only in the realm of its mode. Although there are other topics concerning baptism that may be important in their place, such topics lie beyond the scope of this work's purpose and therefore will not be dealt with in it. It should also be understood that any reference cited within this work does not necessarily constitute and endorsement by the author of any of that person's views, either on baptism or any other subject. Such references that do appear shall be used only as they relate to the subject at hand. Etymology Of "Baptism" Contrary to the opinions of those who maintain such a viewpoint as mentioned above, the study of the etymology of the words "baptism" and "to baptize" reveals that neither of these words could have been invented by the King James Version's translators, but instead it shows that they have a long history of usage behind them. These words have their ultimate origin in the Greek language. "Baptism" is derived from the noun baptisma, which means "a dipping in water."(2) It is found only in the Greek New Testament and later ecclesiastical writings.(3) The verb "to baptize" comes from baptizein or baptizo(4) (both of which are merely two conjugational forms of the same Greek verb stem),(5) both of which have the meaning "to dip, to immerse, submerge," and have been in existence from at least the time of Plato (c. 400 B.C.)(6) However, these words did not remain dormant for fifteen hundred years as the advocates of the above viewpoint might lead one to believe. From the Greek, these words were assimilated into Ecclesiastical Latin,(7) the style of Latin used primarily by the church fathers of the West. The Latin noun for this ordinance was baptisma ("a dipping" and the verb form was baptizare ("to dip").(8) Tertullian, a leader of the Montanists(9) and the creator of this style of Latin,(10) is credited as being the one who introduced this word into the Latin vocabulary,(11) most likely as a result of his important tract about this ordinance, De Baptismo, written perhaps as early as 190 A.D.(12) These Latin words went on to be adopted into the Old French language,(13) which was spoken from about the middle of the ninth century to about the time of the fourteenth century.(14) In this language the nouns appeared as bapteme or baptesma, and the verb form was baptiser.(15) Both noun and verb forms are cited as being found in an Old French poem entitled Vie de Saint Alexis,(16) written about 1040, (17) which is considered as being "the oldest French poem possessing literary merit."(18) The event that led to the appearance of the forerunners of the words "baptism" and "to baptize" in Great Britain was the Norman Invasion and Conquest of that island by William the Conqueror which began in 1066.(19) Its effects upon the language spoken on the island in general, and on ecclesiastical terminology in particular, were very considerable.(20) Old French-speaking clergymen who came to the island shortly after the invasion brought their words for this ordinance over with them.(21) The extent to which the Old French influenced this ordinance can be seen by the fact that the noun baptesme began to appear in the Old English,(22) the language that was spoken by the island's natives up to about 1150.(23) By the middle of the twelfth century, the language of England had shown sufficient changes from the Old English (Anglo-Saxon) that it was necessary for it to be given a new designation - - Middle English.(24) This form of English was in use form that time up to about the sixteenth century.(25) During that era the word for "baptism" was bapteme.(26) The earliest known work in which this word is recorded is a Northumbrian poem on Biblical subjects entitled Cursor Mundi, written about 1300.(27) The earliest recorded usage of the Middle English equivalent of the verb "to baptize" is in Robert of Gloucester's Metrical Chronicle, written in 1297,(28) a history of England written in rhymed couplets.(29) An even earlier date can be ascribed to the first known occurrence of the Middle English equivalent of the cognate noun "baptist." When referring to Christ's forerunner, the Trinity College Homilies, a collection of sermon manuscripts maintained by Trinity College, Cambridge, England, dated about 1200, uses the word Baptiste.(30) These Middle English words were the last link in the evolutionary process by which the Modern English words "baptism" and "to baptize"came into being.(31) Although the etymological evidence does show that the King James Version's translators could not have invented the words "baptism" and "to baptize," the advocates of the viewpoint under examination could still maintain that the translators may have chosen to use them to conceal their usage of baptismal modes other than immersion - - that is, if other modes were in fact used by them or their ecclesiastical superiors. To find out what baptismal mode was used by such people, one must investigate the history of baptismal modes in England up to the period of the production of the King James Version. the findings of such a study (which necessitates studying not only the history of baptism itself, but also that of Christianity in general on that island) do not afford those who hold to this view much evidence to support their claims either. History Of Immersion For Baptism In England The history of Christianity in England prior to the Norman Invasion of 1066 may be divided into two periods. The first one is considered as being the era of Briton Christianity, which began with the introduction of Christianity in that land until the time of the invasions by the Anglo-Saxons in the middle of the fifth century.(32) The second period is that of Anglo-Saxon Christianity, which had its start with the founding of a Catholic mission to these barbarians at the end of the sixth century and lasted until the Norman Invasion.(33) To assign a date for or to cite the name of the one who first brought the Christian Gospel to England is an impossibility. Almost a dozen legends about this do exist, all claiming to be the answer to this issue, all in conflict with each other, and none of which can be conclusively verified. However, it can be safely asserted that Christianity was known in Britain in the second century(34). The baptismal mode used by the Christians of that age was immersion(35). For about 300 years Christianity flourished on the island, but this first period was brought to an abrupt end when the barbaric Anglo-Saxon tribes began to invade Britain towards the middle of the fifth century, forcing those who remained of the Britons into isolated regions along the island's western coast line(36). During the interval between the first and second periods of Christianity in England lived a man who is well remembered even today: St. Patrick. His ministry included not only the Irish, but it extended to what is now known as Scotland and even among the Britons who had managed to escape the ravages of the Anglo-Saxons. The mode he used to baptize his converts was immersion(37). The year 597 marks the beginning of the period of Anglo-Saxon Christianity, an era that was ushered in by Augustine, the so-called "Apostle to the English" and personal envoy of Pope Gregory the Great(38). Augustine's labors among these people became very successful, and when he baptized he sought the use of rivers in order to perform total immersion(39). With regard to the mode of baptism, the subsequent years, both prior to and following the Norman Conquest, saw none other than the use of immersion in England. Venerable Bede (c. 700), the "father of English theology and church history(40)," held to a dipping in water as necessary for baptism(41). In 816 the Council of Calichyth, held under the auspices of the Mercian King Kenwold, strictly forbade any other baptismal mode except immersion(42). The Constitutions of the Synod of Amesbury in 977 recounted the widespread use of immersion in the island(43). A series of six church councils held in various English cities from the year 1200 to 1296 all admonished baptism to be performed by immersion(44). William Tyndale (1484-1586), the famous Bible translator, considered baptism as being a plunging in water(45). The reign of the Tudor family over England (1485-1603) saw many changes in the nation's religious life. It was during Henry VIII's reign (1509-1547) that the Church of England was founded in the year 1534(46). That baptism by immersion was still practiced is evident by the fact that he, his older brother Arthur, his sister Margaret, King Edward VI, and Queen Elizabeth I were all immersed(47). The turbulent era of the Catholic Queen Mary (1553-1558) was one in which only immersion was permitted(48). Christian states that "immersion was almost the universal rule in Elizabeth's reign"(49) (1558-1603) and refers to an important book entitled Reformation Legum Ecclesiasticarum which was written and published by high Anglican officials in 1571 and which required immersion for the Church of England's baptism(50). Although other modes for baptism did start to make their way into England about the beginning of the Stuart family's reign in England (1603), King James I (r. 1603-1625), the one for which the King James Version was named, was not an advocate of these other modes(51). Anglican officials consistently fought attempts to introduce sprinkling and pouring into the Church of England during the reign of Charles I (1625-1649)(52). As history bears out, it was not until 1644, thirty years after the King James Version, that the British Parliament, then under the control of the Presbyterians (who were temporarily able to wrest the political power from the Anglicans as a result of the English Civil War), decreed immersion as illegal in English churches(53). It is evident, therefore, that the history of the mode of baptism used in England confirms the fact that immersion had always been the predominant mode throughout all the years prior to an during the period of the work on the King James Version. The advocates of the viewpoint under examination have neither the findings of the disciplines of etymology nor history as a basis upon which their contentions may be proven. Not only does the negative evidence from these two studies invalidate their claims, but also, when these are coupled with the application of the discipline of semantics, there are other factors which make their assertions to be quite illogical. Semantical Relationships Of "Baptism" To The Translators In semantics, which is the study of the significance of words and the concepts to which they refer,(54) there is a basic principle that what a word means to its users is determined by what the users do with it(55). For the purpose of this study, this principle may be stated in the form of a question: Did the words "baptism" and "to baptize" mean "immersion" and "to immerse" to the King James Version's translators, i.e., were they synonymous to each other? There are three key sources of evidence which practically demand an affirmative answer to this question. The first of these decisive factors is that every Bible written in English from that of John Wycliffe's version,(56) the very first English Bible (c. 1384),(57) to that of the Rheims New Testament,(58) the Roman Catholic version of the English New Testament and the last English Bible to be produced prior to the King James Version (1582), all use either the exact words "baptism" and "to baptize" or their contemporary equivalents in their texts. What did the users of these Bibles take these words to mean? The study of the baptismal mode in England indicated that they all understood them to mean "immersion" and "to immerse." Secondly, facsimile reproductions of Baptist confessions of faith written in English, from before and on up to the very year that the King James Version was produced, all employ those exact words or their contemporary equivalents when referring to this ordinance(59). What did the users of these confessions of faith take these words to mean? It is common knowledge that the Baptists have had the historical distinction of being immersionists, and the Baptist of England at that time were no exception. Finally, perhaps the most devastating evidence of all to disprove the allegations of the viewpoint being examined is the testimony of the King James Version's translators themselves. As was indicated in the study of the history of the baptismal mode in England, other modes for baptism did begin to come into England by the turn of the seventeenth century. However, the people who practiced these other modes were not primarily those of the old-line Anglian persuasion but rather were those of the faction called Puritans, who probably had picked up the usage of these modes from the influence of Continental reformers with which they had come into contact when the majority of the leaders of this faction were temporarily forced into exile from Great Britain to the Continent during the reign of Queen Mary.(60) Although this faction did play an important role in prompting the idea for a new Bible (the result of which was the King James Version), only four of the forty-seven translators were Puritans.(61) In the Translators Preface of the King James Version, "The Translators to the Reader," which presently is seldom printed in the King James Version Bible, they have this to say about the words "baptism" and "to baptize" in their work: (d) We have on the one side avoided the scrupulosity of the Puritans who leave the old ecclesiastical words, as when they put washing for baptism....(62) From this statement by the translators themselves, it is obvious that, if they had had the Puritan baptismal modes of sprinkling or pouring in mind when they worked on the King James Version, they would not have used the words "baptism" or "to baptize" at all but would have used "washing" or "to wash" instead. They did not use the latter two because they wanted to employ the words that, to them, aptly expressed the Anglican concept of the mode of immersion -"baptism" and "to baptize." Conclusions To Be Drawn The evidence from etymology, from history, and from semantic reasoning, shows that the King James Version's translators did not coin the words "baptism" and "to baptize" as a deceptive front to hide the practice of sprinkling or pouring for baptism. To say that they did is totally unsubstantiated charge because: (1) These words already existed. (2) The Church of England, of which practically all the translators were high officials, still practiced immersion when the King James Version was produced. (3) If the translators had intended to convey the idea of baptismal modes other than immersion, they would not have used "baptism" and "to baptize" when they translated the references to this ordinance anyway. It is hoped that this work will help to show the innocence of the translators of the King James Version to the charge that has been thoughtlessly thrown at them and to give the users of this version another reason for them to assert that the King James Version is still the most reliable English translation available to the public today. FOOTNOTES 1. A representative sampling of this viewpoint, in whole or in part, may be found in (but not limited to) these sources: Milburn Cockrell, "The Proper Mode of Baptism," The Baptist Examiner, XLI (January 5, 1974), 1: E.G. Cook, Let's Study Revelation (Ashland, KY., 1970), p. 167; William Manless Nevis, Alien Baptism and the Baptists (Ashland, KY., 1962), p. 17; J.M. Pendleton, Baptist Church Manual (Nashville, 1966)< pp. 65-69; and Kenneth W. Wuest, "Romans in the New Testament," Wuest's Word Studies in the Greek New Testament (Grand Rapids, Mich., 1966), I. 96. 2. Ernest A. Klein, A Comprehensive Etymological Dictionary of the English Language (New York, 1966), I, 147. 3. Joseph Henry Thayer, Thayer's Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament (Marshallton, Del., n.d.), p. 94. 4. Klein, loc. cit.; and C.T. Onions and others, The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology (New York, 1966), p. 74. 5. J. Gresham Machen, New Testament Greek for Beginners (New York, 1951), p 584. 6. Thayer, loc. cit. 7. Klein, loc.cit.; and Onions, loc. cit. 8. Ibid. Se also Charton T. Lewis and Charles Short, Harper's Latin Dictionary (New York, 1907), p. 221. 9. Phillip Schaff, History of the Christian Church (n.p., n.d.), I, 378. 10. James H. Martinbrand, Dictionary of Latin Literature (New York, 1956), p. 274. 11. Lewis, loc. cit. 12. Schaff, loc. cit See also Augustus H. Strong, Systematic Theology (Valley Forge, PA., 1907), pp. 936-937 13. Onions, loc. cit. 14. Mario A. Pel and Frank Gaynor, dictionary of Linguistics (New York, 1954), p. 153. 15. Onions, loc. cit. 16. Oscar Bloch and W. Von Wartburg, Dictionaire Etymologuique de la Langue Francaise (Paris, 1950), p. 55; and Albert Dauzat, Dictionnaire Etymoloqique de la Langue Francaise (Paris, 1938), p. 73. 17. H. Stanley Schwartz, An Outline History of French Literature (New York, 1929), p. 13. 18. Edward Dowden, A History of French Literature (New York, 1929), p 14. 19. Albert C. Baugh, A History of the English Language (New York, 1963), p. 127. 20. Ibid. 21. Ibid. , p. 203; and Lincoln Barnett, The Treasury of Our tongue (New York, 1966), p. 132. 22. Klein, loc. cit. 23. Baugh,op. cit., p. 159. 24. Ibid., pp. 200ff. 25. Ibid., p. 59. 26. Klein, loc. cit.; and Onions, loc. Cit. 27. James Murray and Others, eds. The Oxford English Dictionary (London, 1933), I, pp. 659-660; and Baugh, op. cit., p. 164. 28. Walter W. Skeat, An Etymological Dictionary of the English Language (London, 1963), p. 47. 29. "Robert of Gloucester," Encyclopedia Americana, International Ed., 1973, XXIII, 567. 30. Murray, loc. cit. 31. Klein, loc. cit.; and Onions, loc. cit. 32. John Henry Kurtz, Text-book of Church History (Philadelphia, 1880), p. 297. 33. Baugh, op. cit., p. 133. The Norman Conquest had little effect on the English Church doctrinally, but a majority of church offices changed hands as native leaders were replaced by men from the Continent. 34. John F. Hurst, History of the Christian Church (New York, 1900), I, 575ff. 35. Ibid., p. 583. 36. Kurtz. loc. cit. 37. John T. Christian, A History of the Baptists (Texarkana, TX-AR, 1922), p. 178. 38. Ibid., p. 179. This Augustine (also called Austin) should not be confused with St. Augustine, Bishop of Hippo in North Africa, who lived some 200 years earlier. Scaff, op. cit., II, 399-403, 14-16. 39. John Godfrey, The Church in Anglo-Saxon England (London, 1962), p. 372. 40. Schaff, op. cit., II, 19. 41. Thomas Armitage, A History of the Baptists (New York, 1887), p. 426. 42. Ibid. 43. Thomas Collier, Ecclesiastical History of Great Britain, I, 471, cited in Christian, op. cit., p. 182. 44. Armitage, op. cit., p. 427. 45. Christian, op.cit., p. 188. 46. Roy Mason, The Church that Jesus Built (Tampa, n.d.), p. 53. 47. Christian, op. cit., pp. 427-428. 48. Christian, op. cit.,, p. 204. 49. Ibid., p. 213. 50. Ibid., pp. 296-297. 51. Pendleton, op. cit.,, p. 69. 52. Christian, op. ., pp. 287-288. 53. Ibid., pp. 296-297. 54. Pel and Gaynor, op. cit., p. 193. 55. Louis B. Salomon, Semantics and Common Sense (New York, 1966), p. 51. 56. Francis Henry Stratmann, A Middle English Dictionary (London, 1963), p. 43. 57. Schaff, op. cit., III, 157. 58. Luther A. Weigle, ed., The New Testament Octapla (New York, 1962), passim; and Eugene Cumminskey, ed., The Holy Bible Translated from the Latin Vulgate (Boston, 1852), passim. 59. William Lumpkin, Baptist Confessions of Faith (Philadelphia, 1959), pp. 93,111,119- 120. 60. Pendleton, loc. cit. 61. Terence H. Brown, "The Learned Men," Which Bible?, ed. David Otis Fuller (Grand Rapids, Mich., 1971) pp. 14-22. 62. Henry Barker, English Bible Versions (New York, 1907), pp. 171-172.