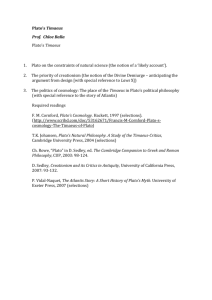

A Critique of Plato`s ideas in the Republic

advertisement

A Critique of Plato’s ideas in the Republic. The theory of forms. This idea underpins much of Plato’s philosophy. As Warburton observes, “Without it, it is difficult to see how Plato can overcome the problem of the one and the many, nor justify the concept of the philosophy ruler.” He must locate certainty outside the changing world of the senses and so, the metaphysical idea of the forms is postulated. Is this reasonable? Possibly not: Aristotle famously criticised the theory of forms on empirical grounds - if the senses cannot access the forms, then on what grounds may it be said to exist? Where do we draw the line? Plato seems to argue that types in the physical realm are represented in perfection in the world of forms. Such a proposition seems open to ridicule. i.e. if there is a form of a parrot, is there also one of a one legged parrot? Or a one legged, hunchbacked, blind parrot with a stammer?! If these things feature in the physical world, then surely they herald from the world of forms. How Plato understood the relationship between the forms and sensible particulars is not clear. The Third Man Argument (Mentioned by Plato in the Parmenides and developed by Aristotle) – infinite regress of forms. i.e. If there is a form of x (x1), then x and its form must share in something. This would then require another form (x2) which represents both x and the form of x. But, then x, x1 and x2 also share in something and would necessitate a form to represent this – x3! This process continues ad infinitum. R E Allen attempts to counter this argument, stating that x and the form of x should be understood in equivocal terms (used in different ways). The role of the soul The forms can only be known because the soul has once witnessed them. The soul longs to repeat this experience and draws human beings in pursuit of its perfection. Yet, this idea presumes the existence of a soul. Without a soul it is difficult to see how the forms could be known at all to those in the physical realm. Thompson criticises Plato’s belief that the only thing to be valued in the physical world is the soul. He argues that such emphasis is inconsistent with our experiences – when we experience physical pain, it seems very important to us! In addition, Plato’s fascination with Politics and the like seems to indicate that he gives greater credulity to the physical world than he is prepared to admit. Knowledge and Belief (& ignorance) Plato is concerned with knowing what something is. His quest is to uncover the essential nature of those things we experience (what Kant refers to as the noumina). Yet, can this quest ever be accomplished? How would we know when such knowledge is acquired? Can we be certain that there is nothing of “what is not” in our understanding? E.g. Before the Copernican revolution we “knew” that the sun rotated around the earth! Plato also insists that virtue is knowledge – no one does wrong willingly. Peter Vardy disagrees. He uses the example of smokers, arguing that such people know that what they are doing is damaging to themselves and those around them, yet they still wilfully smoke! The Philosopher. Both Vardy & Warburton observe that Plato’s utopian ideal is essentially elitist. Power is extended to a privileged few and there is to be no opportunity extended to those who are considered inferior – the noble lie (Gold in the soul of the philosopher etc). In addition, Plato seems to detract from his deontological standpoint in advocating the noble lie. This is a utilitarian mechanism – allowing the “evil” of dishonesty in order to secure the “good” of contentment for the majority. Warburton also argues that the analogy between the individual and the state is weak i.e. because wisdom must rule in the soul, the philosopher must rule in the state. Society’s rejection of philosophy. Plato places much of the blame on the sophists. He argues that it is through their relativism that philosophy has acquired a bad name. Yet, many would claim that this is unfair. Many of the sophists were highly respected teachers whose knowledge surpassed most. We might argue that society is right to fear philosophy – at least right to fear Plato’s brand of philosophy. To accept Plato’s ideas is to accept “…censorship not free speech, elitism not democracy, and the murder of children if the state found it convenient.” (Pinchin). The simile of the ship It could be argued that Plato underestimates the power and credibility of the people? Perhaps the captain will listen to the navigator? i.e. the electorate may opt to embrace the wisdom of the philosopher. Plato’s lack of faith in the ways of the common man is overtly cynical. Hamilton insists that there is a problem with the analogy as the science of navigation is very different from the art of politics. The simile of the large and powerful animal. Are political leaders so irresponsible? Many would argue that most democratic leaders come to power with a vision and a desire to change things for the better. Whether they manage this or not is a different matter. Yet, the fact remains that there are at least some who are prepared to take tough decisions, knowing full well that their actions may be against public opinion. E.g. Blair on Iraq?! It may also be argued that the relativism encouraged by democracy and taught by the sophists represents a far more reasonable picture of reality than Plato’s theory of forms! The form of the Good. Mel Thompson quite rightly asks “how are we to know what goodness is?”. It is an obvious criticism of any philosopher arguing an absolutist position. “Different philosophers can have different conceptions of the good and it is not clear what rational procedure could solve such disputes.” (Pinchin). Can Plato really make a claim to know the Good? How could such a claim be verified? Also, if the Good is beyond the experience of most people, then how can we expect them to believe in it? Again, Plato’s elitism does not appear particularly palatable. The simile of the sun It is only through the light of the good that anything can be known. Thus, Plato seems to be suggesting that things can only be known from a moral perspective. Everything has a moral dimension. Is this acceptable? Hamilton thinks not – one can have knowledge of a blue sky, but where is the moral perspective?! In defence of Plato, Taylor argues that the good is to be understood in a teleological way, not an ethical way. To know something is to know how it orientates us towards the good. The simile of the divided line. Plato presents a hierarchical structure of knowledge. The lowest stage- illusion, is considered far removed from the concerns of the philosopher, but is not some degree of illusion always going to be present in individual knowledge? Plato believes that the philosopher will master all branches of knowledge. Yet, this would seem an impossible goal in the modern world. The stage of mathematical reasoning is difficult to clarify. It seems more strongly attached to the physical world than Plato is prepared to admit, at least in its conceptual stage. Further, the leap from mathematical understanding to absolute knowledge is difficult. To some philosophers, it seems totally implausible to suggest that Plato can progress beyond the third stage in his simile of the divided line. Mathematical reasoning attempts to construct universals, but draws from phenomena in doing so. The fourth cannot be reached as it is severed from any tangible point of reference in the physical world. “We may well conclude that nowhere in The Republic does Plato himself go further than the third stage of the line.” (Norman). The simile of the cave. Vardy asks “How does one know that one has emerged from the cave and is not still in shadow?” It is not clear how the “would be philosopher” will know that he has graduated! Would the cave dwellers necessarily kill the returning philosopher? Could it not be possible that some would be grateful for his insight? Is this another example of Plato being overly cynical of his fellow Athenians? Some final thoughts. In an empirical age, Plato’s ideas can appear fantastical and certainly impractical. His absolutist stance does not rest well with popular moral relativism and his emphasis on certainty can seem arrogant. However, it may also be argued that those who are uncomfortable with such ideas represent the aspects of modern life that need to be challenged! Plato’s strong line on the truth is refreshing in a post modern age that seeks to reduce all value to personal preferences. We may also argue that if there is no such thing as truth, the questions that we now ask are pointless anyway!