`Research Methods` portfolio? - Research Skills Online

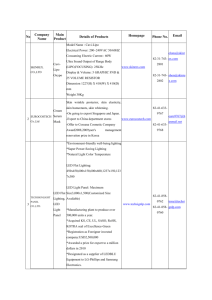

advertisement

RESEARCH SKILLS MASTER PROGRAMME: ‘RESEARCH METHODS’ PORTFOLO 1 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION TO THE RESEARCH SKILLS MASTER PROGRAMME: ‘RESEARCH METHODS’ PORTFOLIO RESEARCH METHODS IN THE ARTS & HUMANITIES RESEARCH METHODS IN THE SOCIAL SCIENCES RESEARCH METHODS IN THE SCIENCES RESEARCH METHODS IN LITERATURE REVIEW 2 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | 3 6 17 38 49 INTRODUCTION TO THE ‘RESEARCH METHODS’ PORTFOLIO 3 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH SKILLS MASTER PROGRAMME: Introduction to the ‘Research methods’ portfolio What is the ‘Research Methods’ portfolio? Welcome to the ‘Research methods’ portfolio. This document accompanies the four courses on ‘Research methods’ in the Research Skills Master Programme. What is the ‘Research methods’ portfolio? This portfolio is intended to supplement and enhance your learning as you progress through the Research Skills programme in the following ways: The portfolio draws together all of the documents and supplementary materials available to download throughout the main course, so that they are easily accessible from a single location. Throughout the main course, you will be invited to undertake various reflective and supplementary activities (called ‘Portfolio activities’). These are accompanied by the portfolio icon, above. The portfolio provides a space for you to record your thoughts for each of these activities. You may like to return to these notes and extend or refine them as you progress through the programme. Your portfolio should continue to prove an invaluable tool once you have completed the Research Skills programme, with summary sheets, templates, and your own notes and reflections providing a useful reference manual for the duration of your research career. 4 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH SKILLS MASTER PROGRAMME: Introduction to the ‘Research methods’ portfolio Your ‘Research methods’ portfolio: How to use this document How do I use my portfolio? Save a copy of this document on your computer. Keep the portfolio open as you work through the Research Skills programme. Each time you undertake a ‘Portfolio activity’, or are asked to keep a note of the results of an in-course activity, you will find a corresponding page in this document for you to complete. (See ‘How do I navigate my portfolio?’ below for more details.) Refer to, or complete, each portfolio document as instructed in the corresponding section of the main course. How do I navigate my portfolio? To navigate your portfolio easily, ensure that you have the ‘Document Map’ or ‘Navigation Pane’ feature in Microsoft Word enabled. To do this, go to ‘View’ and tick ‘Document Map’. On the left-hand side of your screen you will see each of the three ’Entrepreneurship’ courses listed, followed by its accompanying portfolio documents, in order of appearance in the programme. The titles in the ‘Document Map’ correspond with the course screen titles to enable you to easily locate the desired document. The course and module are also displayed at the top of each portfolio document for ease of use. Click on a course title or a document name to jump to that section of the portfolio. Where a section in the main course has more than one portfolio document associated with it, the documents are numbered in brackets in order of appearance in the corresponding section of the main course. 5 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN THE ARTS AND HUMANITIES 6 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN THE ARTS AND HUMANITIES: Orientation Learning outcomes Before you begin this course, take a moment to reflect on the learning outcomes presented in this section, and your current awareness and understanding of different research methodologies in arts and humanities projects. Do you understand what is meant by 'research methodology'? Have you considered the impact your research methodology might have on the shape of your research project? What research methodology/methodologies might you be using for your own project? Have you thought about how you will critically engage with the material you study as part of your project? Are you familiar with the major different critical theories? Will you apply any of these to your research? Have you thought about taking an interdisciplinary approach to your research? What benefits might this have? What would you like to learn or improve as a result of taking this course? You may wish to make a note of your thoughts in the space below. 7 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN THE ARTS AND HUMANITIES: Introducing research methodology in the arts and humanities The relationship between research questions, research material and research methods Your research methodology Which research methods are you already familiar with? Write a list of different kinds of projects and evidence you have worked with before What research methods did you use? How was your methodology directed by the kind of questions you were asking or by the kind of research material you were using? You may wish to use the table below to record your answers. Estimated duration: 30 minutes Project/evidence Research methods used 8 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | How was methodology directed by questions asked/research material used RESEARCH METHODS IN THE ARTS AND HUMANITIES: Approaching archives, artefacts and other evidence Approaching artefacts Artefacts in everyday life Try using Fleming’s methodology on a material object of your choice: you can select something relevant to your research topic, but it doesn’t have to be related, or even something you might think of as a historical artefact. What can you say about its history, material construction, design and function? Can you specify when you are using processes of identification, evaluation, cultural analysis and interpretation? Record your notes in the space below. Estimated duration: 30 minutes 9 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN THE ARTS AND HUMANITIES: Thinking critically, thinking theoretically Developing your argument Approaching topics from different theoretical angles Practise your critical skills by making a mind map for a research topic on the rise in popularity of home improvement television shows in the United Kingdom in the 1990s. What kind of questions might you ask? What kind of different questions might a sociologist ask? How about a historian? How about someone interested in gender studies? What research material might these questions suggest? Can you come up with some hypotheses that you could test and explore? Select one or two of your hypotheses and put them into order by translating them into an argument map. You may wish to repeat this process in relation to your own research topic. Reflect on whether it raises any questions or identifies any research material that you hadn’t previous considered. Estimated duration: 30 minutes 10 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN THE ARTS AND HUMANITIES: Thinking critically, thinking theoretically The place of theory Different theoretical approaches Taking a particular theoretical approach will affect the kind of research material you will use and the kind of research questions you might ask. Estimated duration: 30 minutes Consider the development of department stores in London in the early part of the twentieth century from both a Marxist approach and a feminist approach. What different kinds of research questions might they ask? a) Marxist approach b) Feminist approach Now consider different theoretical approaches in the light of your own research project: 11 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN THE ARTS AND HUMANITIES: Understanding disciplinarity and interdisciplinarity Disciplinarity and interdisciplinarity in the humanities Interdisciplinarity in your own research Consider whether there is an interdisciplinary element to your own research Draw a Venn diagram to illustrate the different disciplinary subject matter and research practices that you might need to familiarise yourself with Estimated duration: 40 minutes 12 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | Can you consider at least three ways in which aspects of your research might become more interdisciplinary? To you help you do this, consider: If a scholar from a different discipline was looking at my topic, what kind of research questions might they ask? Would they be very different from my own research questions? Are there ways I could incorporate their questions into my research? Would scholars of different disciplines be looking at different kinds of research material from me? What sort of material might they be using? Is there a way I could carefully use this material in my own research? Make a note of your responses in the space below. 13 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN THE ARTS AND HUMANITIES: Is it working? Identifying and avoiding common problems (1) Tips for managing the scope and volume of your research Begin with clearly defined research questions, discussed and agreed with your supervisor. Although you will probably modify and refine your questions as your research develops, it is crucial that you keep them in focus throughout the research and writing stages of your work, and speak to your supervisor if you feel that you are losing control of your material. Remember that not all the material you discover necessarily has to go into your final thesis – indeed, if it is not strictly relevant then it probably shouldn't do. But this is not to say that you have wasted that work. It could instead be the groundwork for a conference paper or journal article. 14 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN THE ARTS AND HUMANITIES: Is it working? Identifying and avoiding common problems (2) Making the best use of your material Identify whether you have some primary material which you cannot use in your PhD project, either because it is not entirely relevant or you do not have the space for it Consider whether the material could form the basis of a separate conference paper or journal article, and whether you could perhaps collaborate on it Speak to your supervisor and/or do some research on finding a suitable conference or journal to which you could submit. You may wish to record your thoughts in the table below. Estimated duration: 60 minutes Primary material Notes from discussion with supervisor 15 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | Results of research into suitable conference or journal RESEARCH METHODS IN THE ARTS AND HUMANITIES: Learning assessment Learning evaluation Take a moment to consider the reflective piece you wrote before undertaking this course. Think about the questions you answered and the goals you outlined at the start of the course. To what extent do you feel you have met the course learning outcomes, and your own learning needs? Do you feel better able to apply your knowledge to your own research? You may wish to make a note of your thoughts in the space below. 16 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN THE SOCIAL SCIENCES 17 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN THE SOCIAL SCIENCES: Orientation Learning outcomes Before you begin this course, take a moment to reflect on the learning outcomes presented in this section, and your current awareness and understanding of the process of publishing your research. Do you understand the difference between a positivist approach and an interpretative approach in research in the social sciences, and where your own research sits within these approaches? How familiar are you with common research designs, and do you know which design(s) you might use for your own study? How familiar are you with different data collection and analysis methods, and do you know which you might use for your research? How much do you know about the process of publishing your research? What would you like to learn or improve as a result of taking this course? You may wish to make a note of your thoughts in the space below. 18 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN THE SOCIAL SCIENCES: Before you get started Epistemology: The study of knowledge Positivist and interpretative approaches Think about the examples of positivist and interpretative approaches in this section, and then think about your own research topic. How might you consider it in the light of the positivist and interpretative approaches? Which approach might be more suitable for your research project? You may wish to record your thoughts in the space below. Estimated duration: 20 minutes 19 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN THE SOCIAL SCIENCES: Framing your research question What makes a good research question? Rewording your research question Having considered the advice in this section, try writing and re-writing your research question in as many different ways as possible. How does wording your question differently frame the question in a different way? Which wording might be suitable for your research project? Remember to consider all the elements of a good research question outlined in this section of the main course. You may wish to record your ideas in the space below. Estimated duration: 30 minutes 20 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN THE SOCIAL SCIENCES: Framing your research question The implications of your research question Considering the possible outcomes of your research question Think about your own research question. Write down all the possible outcomes or findings you might end up with as a result of your study. What would be the implications for each finding? Consider whether you might need to alter your research question or design as a result of this exercise. Estimated duration: 40 minutes Possible outcomes/findings of your study Implications 21 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | Do you need to change your research question as a result of the above exercise? If so, make a note of some options in the space below. 22 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN THE SOCIAL SCIENCES: Framing your research question Your values and priorities Preparing for external influences on your research Think about the issues identified in the corresponding section of the main course. Estimated duration: 20 minutes What values, assumptions or experiences might influence your approach to your research? How will they influence it? Are any of the ‘external’ considerations in the final activity in this section applicable to you? Will you need to take them into account when designing your research? 23 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN THE SOCIAL SCIENCES: Framing your research question Resources, time and feasibility (1) Considering your resources Write down – realistically – what resources you have available to you. For example, think about the facilities and human resources you will need, and the funding you have. Be realistic about the input you can expect from others, including your supervisors. If you do not have additional funding to support your research, you need to make sure you can fund the project as it is unlikely that there will be additional resources to support you. You may wish to record your thoughts in the space below. Estimated duration: 20 minutes 24 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN THE SOCIAL SCIENCES: Framing your research question Resources, time and feasibility (2) Planning your time Take a moment to consider how much time you have available to complete your research, and how long each stage of your research will realistically take you. You might like to use the table below to record your thoughts, and the space beneath it to record any feedback from a discussion with your supervisor. Estimated duration: 30 minutes Stage of research Duration of stage 25 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | Feedback from discussion with supervisor: 26 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN THE SOCIAL SCIENCES: Planning considerations Research ethics Considering others when planning your research Consider the examples of those who might be adversely affected by a research project in the corresponding activity in this section. Estimated duration: 45 minutes Do any of these examples apply to your own research? Can you think of any other individuals who might be affected by it? What steps can you take to minimise any adverse effects on others? 27 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN THE SOCIAL SCIENCES: Planning considerations Qualitative versus quantitative The influence of different approaches Search for research that has been done in your area, and consider whether it has been done using a qualitative or quantitative approach. How might these different approaches influence the way you design your project? You may wish to record your thoughts in the space below. Estimated duration: 45 minutes Research Approach Influence on my project 28 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN THE SOCIAL SCIENCES: Designing your research Some design examples Different research designs explained This document will give you some more detailed information on the different types of research design introduced in this section of the main course. Case studies A case study usually involves a sample of one. You can use a case study to do a very in-depth study of what is going on within that sample, identifying key issues and processes to be followed up later with other designs and larger samples. A common example is using one organisation as your case study, often, your own organisation or one where you happen to have contacts. Case studies can be good for using in-depth methods, which would take too long to use on a larger sample size. This can be very useful for identifying what the real underlying issues are, if you're tackling a problem where it's not obvious. Case studies can also be useful as a clear, specific illustration of principles that occur widely. A famous example is Faraday using a single candle to demonstrate the key principles of thermodynamics. They can also be invaluable as examples of a 'white crow' finding, where one single example is enough to disprove a claim: for instance, finding one white crow is enough to disprove the claim that all crows are black. They are also useful for 'demonstration of concept' studies, where you show that something is possible which had not been done before. Case studies have limitations. The most obvious is small sample size. You have no way of being sure how representative your sample is of the world at large. With a case study, you're also totally dependent on that single case for your data. If you have to abandon that case study because of a change of manager in the organisation who decides to stop helping you, for example, then you may have serious problems finding a new one. If you do find a new one you will probably have to start right at the beginning again and be unable to use any findings from the abandoned study. Some case studies observe the case without trying to intervene, others involve a deliberate intervention and this is usually known as action research. Action research is popular in some disciplines but unpopular in others, because it's not usually possible to untangle effects caused by the intervention from effects caused by outside factors. Action research Action research involves systematically combining action and reflection with the aim of improving practice. It is usually incorporated into work roles by practitioners (e.g. teachers). Action research gives rich information about issues and processes involved. It is often a convenient approach for part-time students who can do action research in the organisation where they work, and can be useful for the host organisation if the intervention works well. 29 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | However, small sample sizes mean that it can be difficult to generalise the findings. There are usually problems with observer effects, and it can be difficult to distinguish results caused by the intervention from results caused by other outside factors. It can be costly for the host organisation if the intervention causes unexpected problems. Field experiments A field experiment involves performing an intervention systematically in the outside world, as opposed to in your office or in the respondent's house. For example, if you are studying the effects of music on social behaviour, you might get a street musician to play different types of music near an office doorway and then observe whether the number of people holding that door open for other people varies with the type of music being played. A well-designed field experiment will usually have fairly high external validity and can give you a respectable sample size. However, field experiments are dependent on the outside environment, so if, for example, you are interested in how a particular social group behaves in a given situation but none of them happen to pass by the place where you are doing your field experiment, then you have problems. They can also raise ethical problems, depending on the type of intervention involved. Controlled experiments A formal, controlled experiment involves varying one or more factors systematically, while keeping all the other factors constant and then seeing what happens to one or more variables. A classic early example involved finding out the cause of scurvy, a disease which frequently used to affect sailors at sea. A naval surgeon divided sailors with scurvy into several groups, with each group as similar to the others as possible, and then gave each group a different treatment and observed what happened to their health. In this example, the treatment was varied systematically between the groups. The factor that is being varied systematically is known as the independent variable. The thing being observed, in this case the sailors' health, is known as the dependent variable, because its value is expected to depend in some way on the value of the independent variable. A properly designed controlled experiment allows you to establish cause and effect, to measure the strength of an effect and to separate the effects of one variable from the effects of other possible variables. Controlled experiments are usually combined with statistics, particularly inferential statistics. Inferential statistics allow you to calculate how likely it is that your results are due to something other than random chance variations in your sample. (Descriptive statistics, in contrast, simply summarise your results.) Conducting a controlled experiment properly involves careful attention to detail and may be time-consuming. As most controlled experiments involve respondents in an unusual situation there can be issues about the external validity of the findings. This is why controlled experiments are usually preceded by pilot studies to check that the experiment will have acceptable external validity. There are numerous classic experimental designs, each suitable for different purposes and situations (for example, designs involving groups which contain different numbers from each other versus groups which contain the same numbers, or designs involving repeated measures on respondents versus designs involving only a single measure on each respondent). Each design is usually suitable for a limited number of statistical tests. If you use the correct design and corresponding statistical test, this can dramatically reduce the amount of data collection you need to do. If you are planning to conduct a controlled experiment, then it is highly advisable to ask an expert for advice as early as possible in the planning stage. This can avoid a lot of problems and can lead to much better work. 30 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | Ethnography Ethnography involves working and/or living with the people you are studying. This approach can lead to much richer information than you would get from an interview, including visual information, everyday detail that people forget to mention in interviews and questionnaires, and access to information that isn't usually shared with outsiders. However, this approach is usually very time-consuming (weeks or months in the field). The information is usually in a format which is difficult to summarise and write up, and there may be ethical questions over disclosing information given in confidence when you write up your results. Simulations Simulations involve building a working model of something, and seeing what happens when the model runs. The model is usually a simplified version of the real-world phenomenon being studied and is frequently software-based, although this is not obligatory. Some problems are better modelled using mechanical models. Simulations can be invaluable for gaining insights, particularly into areas that are difficult or impossible to study in other ways, such as flocking behaviour in flying birds. Software simulations showed that you could produce realistic simulations of this complex-looking phenomenon using only a small set of simple variables. This approach is now widely used to simulate the behaviour of human crowds and has practical applications, such as designing fire exits in aircraft. Simulations can give interesting insights, but this does not guarantee that the processes in the simulation are the same as the processes in the real-world phenomenon. Very similar surface appearances can be caused by very different deep structures. Simulations can also be affected by unintended side-effects of the technology used in the simulation. For example, the way the software rounds off decimal values may produce accidental and unintended regularities, which may be mistaken for properties of the phenomenon itself, rather than properties of the software language. Surveys Surveys attempt to find out how widespread something is across a population, for example, how many people engage in a particular activity or have a particular belief. An obvious way of doing this is via interviews or questionnaires, but an obvious problem is that they may not tell you the truth. There is a substantial and sophisticated literature on survey design, implementation and analysis. If you are thinking of doing a survey, you should make yourself familiar with this literature, and follow best practice. It's possible to do a survey without asking any respondents to answer any questions. For example, you could do a survey of the ages and types of cars parked outside houses in two different areas, as an indirect indicator of likely income in those areas. Done correctly, a survey can tell you a lot about how widespread something is, and about correlations between it and other factors, such as correlations between income and lifestyle. However, surveys are usually very time-consuming, usually have problems with external validity, involve an agenda of questions set by the investigator and often have low response rates if they are questionnaires. A response rate of below 10% is common for mail shot questionnaires, meaning that the responses are likely to have very low external validity. 31 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN THE SOCIAL SCIENCES: Designing your research Methodology versus ideology Identifying alternative methodologies Think about Peter Ayrton’s recommendation in the video in this section of the main course that researchers use a variety of methodologies to procure more diverse findings. Now take a moment to consider which methodologies might be suitable for your own research. Are there any new or different methodologies that you might now consider using? You might wish to record your ideas in the table below. Estimated duration: 30 minutes Methodology Advantage for my research 32 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN THE SOCIAL SCIENCES: Data analysis The importance of planning your data analysis in advance Comparing qualitative and quantitative analysis Think about the studies you found for the ‘Portfolio activity’ in the ‘Qualitative versus quantitative’ section earlier in the main course. Consider the ways in which the data in the studies has been analysed. If the approaches have been quantitative, can you see clear evidence of how the statistics have been analysed? If the approaches have been qualitative, consider the ways in which the data has been analysed using coding and themes. You might like to use the table below to record your thoughts. Estimated duration: 30 minutes Study Notes on data analysis 33 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN THE SOCIAL SCIENCES: Starting your research Checklist of good and bad ideas Planning your research: Key considerations Who are the main previous researchers in your research field? What are the key findings of previous researchers in your field? Are you flexible in terms of the potential results from your research? How are you going to analyse your results? Have you considered the different outcomes that may arise from your research? Is your research design original? Have you identified risks in your research and do you have a contingency plan in place? 34 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN THE SOCIAL SCIENCES: Reporting your research Writing up and audiences (1) Considering the types of publication in your area Have a discussion with your supervisor about the different types of publication in your area. After your meeting, think about: Which topics you are particularly interesting in developing The timeframe you can realistically work to. Write your notes in the space provided below. Estimated duration: 45 minutes Write your notes here: 35 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN THE SOCIAL SCIENCES: Reporting your research Writing up and audiences (2) Tailoring your article to specific journals If you are considering preparing a journal article, have a look at the different journals in your professional area and review the guidance for authors. Consider: Whether the journal editors are looking for short or long papers The type of studies commonly published The scope of academic papers covered in the journal. You may wish to use the table below to record your thoughts. Estimated duration: 45 minutes Journal title Long or short papers? Type of studies commonly published 36 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | Scope of papers covered in journal RESEARCH METHODS IN THE SOCIAL SCIENCES: Learning assessment Learning evaluation Take a moment to consider the reflective piece you wrote before undertaking this course. Think about the questions you answered and the goals you outlined at the start of the course. To what extent do you feel you have met the course learning outcomes, and your own learning needs? Do you feel better able to apply your knowledge to your own research? You may wish to make a note of your thoughts in the space below. 37 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN THE SCIENCES 38 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN THE SCIENCES: Orientation Learning outcomes Before you begin this course, take a moment to reflect on the learning outcomes presented in this section. How confident are you in your current ability to formulate an effective research question and to design and plan a scientific research study around it? Have you considered what makes a good research question? Are you familiar with different approaches to experimental design and do you know which approaches would be most suitable for your project? Do you think it is important to consider how you will analyse your data when planning your research design? Have you thought about the practical problems that could affect your research study and how you might manage them? You may wish to use the space below to make a note of your thoughts. 39 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN THE SCIENCES: What is science? What is scientific research? What makes a good scientist? There are a number of excellent online resources which explore this question. Try to find a few key attributes. Which of the attributes that you found do you think you demonstrate? How will they be of benefit over the course of your research? You might like to use the table below to record your thoughts. Estimated duration: 30 minutes Attribute of a good scientist Do I demonstrate this attribute? 40 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | How might this be of benefit? RESEARCH METHODS IN THE SCIENCES: What is science? Types of research The best type of research for your project Which type(s) of research listed in the corresponding activity in this section might be the best match for your research project, and why? Exploratory Observational Survey/sampling Hypothesis testing Modelling and simulation Problem solving. You may wish to use the space below to make a note of your thoughts. Estimated duration: 30 minutes 41 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN THE SCIENCES: Identifying and formulating the research question Finding a question Using different types of evidence to answer your research question Think about a possible research question on which to base your research project. What types of evidence might you use to help frame your question? Evidence might include data and ideas derived from: A literature review An internet search Your own observations or thoughts A pilot study Currently accepted theory Conversations with colleagues/visiting academics Internal and external lectures Even the media, TV shows, newspapers, etc. How will you use this evidence to answer your question? Use the space below to record your thoughts. Estimated duration: 30 minutes 42 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN THE SCIENCES: Identifying and formulating the research question Deconstructing questions Your research question Using the video in this section of the main course as an example, practise breaking down a research question into manageable sub-questions. Write down an idea for a research question in your discipline. Do you think you would be able to answer this question by the end of your PhD? If not, try creating a tree diagram to break the question down into sub-questions until you reach a question that might be manageable for a PhD project. Estimated duration: 30 minutes 43 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN THE SCIENCES: Identifying and formulating the research question Questions worth asking Considering the outcomes of your research question Draw up a table of all the possible results for your prospective research question Would all the potential outcomes be significant in some way? If not, can you modify your research question to ensure that all outcomes would be significant? You might like to use the table below to record your thoughts. Estimated duration: 30 minutes Possible results from prospective research questions Significant outcome? (Y/N) 44 | Page If no, how can you modify your research question? © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN THE SCIENCES: Evaluating research questions Bias and limitations Bias in your own research Estimated duration: 30 minutes Can you think of any examples of bias in relation to your own research? What agendas or assumptions are behind your research question? What decisions have you made about your data collection and analysis? Can you foresee any difficulties in carrying out your experiment(s) which might distort your results? 45 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN THE SCIENCES: Designing and planning your research Pilot studies Preparing for piloting Think about your own research project. Estimated duration: 45 minutes How might carrying out a pilot study help you? What are the things you most want to check in the piloting? What would you do as a fallback if the piloting showed that your original idea wouldn’t work? 46 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN THE SCIENCES: Designing and planning your research Practicalities Your practicalities of your research situation Reflect on the situation in your laboratory and office. Estimated duration: 30 minutes Are all the facilities required in place? Have all the necessary practicalities been taken into account? What, if anything, could be improved? What action can you take? 47 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN THE SCIENCES: Learning assessment Learning evaluation Take a moment to consider the reflective piece you wrote before undertaking this course. Think about the questions you answered and the goals you outlined at the start of the course. To what extent do you feel you have met the course learning outcomes, and your own learning needs? Do you feel better able to apply your knowledge to your own research? You may wish to use the space below to make a note of your thoughts. 48 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN LITERATURE REVIEW 49 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN LITERATURE REVIEW: Orientation Learning outcomes Before you begin this course, take a moment to reflect on the learning outcomes presented in this section, and your current awareness and understanding of the process of publishing your research. Do you understand why a literature review is so important, and the processes involved in undertaking a review? Do you feel confident in your ability to develop a methodical searching strategy for your review? Do you feel confident in your ability to identify different types of literature and whether they will be useful to you? Do you feel confident in your ability to critically appraise the references included in your review? What would you like to learn or improve as a result of taking this course? You may wish to make a note of your thoughts in the space below. 50 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN LITERATURE REVIEW: Planning your literature review What is a literature review? Identifying what you want from a literature review Think about the research project or study that you are about to undertake. Estimated duration: 30 minutes What kind of literature review will you be undertaking? Will you be using a ‘literature review’ approach as the basis of your research project, or do you need to understand what research has been carried out in your field before you begin your own project, that is, undertake a preliminary review? You might want to consider the most important information that you need to identify through your literature review. For example, check whether your research question has been answered before and the previous methods that have been used. Make a note of your findings and thoughts in the space below. 51 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN LITERATURE REVIEW: Planning your literature review Adopting a methodical approach to your literature review Comparing literature reviews from different disciplines Explore some of the literature reviews that have been undertaken within your discipline. How have these been presented? Now consider some reviews that have been done in other disciplines. Did you find any common ground between the two? What were the strongest points of each type that you can use in your own review? You may wish to record some notes on the example reviews in the following table. You could also use the space provided below to list the strongest elements which you might use in your own review. Estimated duration: 45 minutes Review title Discipline Notes Elements to use in my review: 52 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN LITERATURE REVIEW: Planning your literature review Adopting a focused review question Thinking about your research literature review question Define the terms you will use in your literature review. Remember that many terms have different meanings and it is important to be clear about the scope of your review right from the beginning. Write out your literature review question in different ways to see which best reflects the needs of your research project. You may wish to record your ideas in the space below. Estimated duration: 45 minutes Terms to be used in literature review: Different versions of review question: You might consider writing out your question on a Post-it note and posting it anywhere you will see it regularly. Every time you read your question, consider if it is the appropriate question for you. After a week or two, consider these questions: Are you happy with your final question? Does it convey exactly what your literature review is about? Is there anything you would still like to change? 53 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN THE LITERATURE REVIEW: Searching for literature What literature will be relevant to my review? Developing a hierarchy of evidence Try to work out the most relevant types of evidence needed for your review by developing your own hierarchy of evidence below. Consider: Which types of evidence might be stronger than others in relation to your review question? Which types of evidence might you use if you cannot find the strongest evidence? The types of evidence you might consider could include: Systematic reviews Qualitative studies Randomised controlled trials Cohort studies Case-control studies Case reports Editorials Expert opinions Media coverage Eye-witness reports Anecdotal evidence, etc. Remember that it is important to work out your ‘hierarchy of evidence’, which will depend entirely on the nature of both your research and review questions, and the evidence available to you. Estimated duration: 30 minutes 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 54 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN LITERATURE REVIEW: Searching for literature Identifying inclusion and exclusion criteria Your research question: Inclusion and exclusion criteria Think about the research question for your review and write appropriate inclusion and exclusion criteria for your search. Remember to be as specific as you can and remember that the criteria will be a mixture of pragmatism (you may not be able to access all available literature, for example, in different languages) and the needs of your review. Estimated duration: 30 minutes Inclusion criteria Exclusion criteria 55 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN LITERATURE REVIEW: Searching for literature Searching for literature electronically Searching strategies Think about possible keywords that you could use for your literature search. Consider words used in the UK and other countries, and out-of-date or ‘politically incorrect’ terms that might have been used in previous years. Remember that terms which are too broad will retrieve far too much literature and terms that are too narrow might limit your field excessively. Try running different searches using different keywords in databases that are relevant to your subject. Estimated duration: 45 minutes Term Relevance Search results 56 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN LITERATURE REVIEW: Searching for literature Additional searching strategies Alternative methods Sometimes even careful and considered electronic searches do not pull the required information, or an adequate number of resources. As discussed in this section of the main course, there are a number of alternative searching strategies, including: Searching sources by hand Searching indexes of sources Author searching Contacting the main authors in the field Checking citation information. Think about instances in which your electronic database searches have not been successful. For each search term or topic, try the alternative methods listed above, and note down your findings in the table below. Can you think of any other alternative search methods? Add the results of these to your table too. Estimated duration: 45 minutes 57 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | Search term or topic: Alternative strategy Results 58 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN LITERATURE REVIEW: Searching for literature Documenting your searching strategy A summary of your searching methods Documenting your searching strategy will demonstrate that you have undertaken a systematic and comprehensive searching process. Using your summary, it should be possible to replicate your search process to check your findings or build on your search. You may be required to provide a summary of your searching methods as part of your final thesis. Your summary should include: Details of your own ‘hierarchy of evidence’ Details of any inclusion or exclusion criteria you applied Search terms and keywords Strategies you used in addition to searching electronic databases. Using the information that you have built up for the last four portfolio activities in this module, write a summary of your searching strategy below. You may wish to discuss how to present your searching strategy in your thesis with your supervisor. Estimated duration: 30 minutes Write your notes here: 59 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN LITERATURE REVIEW: Evaluation of the literature The need to be critical Considering the credibility of the material in your literature review In the example of the (now retracted) Wakefield paper (1998), we have seen the importance of being critical of the information you use in your literature review. Take some time to think about the material you will use in your literature review. Read and re-read it Is it credible? Can you cite it confidently? Are there any related papers that you should identify in reference to it? You may wish to record your thoughts in the table below. Estimated duration: 45 minutes Material in your review Notes 60 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN LITERATURE REVIEW: Evaluation of the literature Critical appraisal tools Using appraisal tools for your review Search for critical appraisal tools that are used in your research area. You are looking for tools that help you to assess the strengths and weaknesses of literature and consider whether it is useful for your review. Some key texts also contain appraisal tools or they can be found using a generic internet search. This time, you might have to search broadly to find appraisal tools which might be hard to locate. You may wish to record your thoughts in the table below. Estimated duration: 45 minutes Critical appraisal tool Notes 61 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 | RESEARCH METHODS IN LITERATURE REVIEW: Learning assessment Learning evaluation Take a moment to consider the reflective piece you wrote before undertaking this course. Think about the questions you answered and the goals you outlined at the start of the course. To what extent do you feel you have met the course learning outcomes, and your own learning needs? Do you feel better able to apply your knowledge to your own research? You may wish to make a note of your thoughts in the space below. 62 | Page © Epigeum Ltd, 2013 |