Final manuscript

advertisement

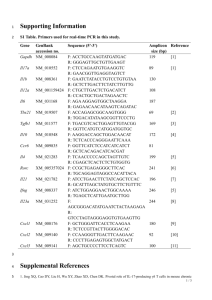

The role of SHIP-1 in T lymphocytes life and death Geoffrey Gloire1*, Christophe Erneux2 and Jacques Piette1 1 Center for Biomedical Integrated Genoproteomics (CBIG), Virology and Immunology Unit, University of Liège, 4000 Liège, Belgium 2 Interdisciplinary Research Institute (IRIBHM), University of Brussels, 1070 Brussels, Belgium. *Address for correspondence: Geoffrey Gloire, CBIG/GIGA, Virology and Immunology Unit Institute of Pathology B23, B-4000 Liège Belgium. Email: geoffrey.gloire@ulg.ac.be. Tel: + 32 4 366 24 26, Fax: + 32 4 366 99 33 Key Words: SHIP-1, T lymphocyte, PI3K, NF-κB, apoptosis, proliferation. ABBREVIATIONS PI3K: phosphoinositide 3-kinase; ITIM: immuno-receptor tyrosine inhibition motif; ITAM: immuno-receptor tyrosine activation motif; Dok: downstream of tyrosine kinase; FcR: IgG Fc receptor; PLCγ: phospholipase C gamma; BTK: Burton’s tyrosine kinase; GSK-3β: glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta; KLF2: Krüppel-like factor 2; NF-κB: nuclear factor κB; IκBα : Inhibitor of κB alpha; TGFβ: transforming growth factor beta. of neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages ABSTRACT SHIP-1, an inositol 5-phosphatase due to enhanced survival and proliferation expressed in hemopoietic cells, acts by of their progenitors. hydrolysing contributes to PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 metabolism the 5-phosphates from Although SHIP-1 phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-triphosphate in T lymphocytes, its exact role in this cell (PtdIns(3,4,5)P3) type is much less explored. Jurkat cells tetrakisphosphate and inositol-1,3,4,5- (InsP4), thereby have recently emerged as an interesting negatively regulating the PI3K pathway. tool to study SHIP-1 function in T cells SHIP-1 plays a major role in inhibiting because they do not express SHIP-1 at the proliferation of myeloid cells. As a result, protein SHIP-1-/- mice have an increased number reintroduction experiments in a relatively level, thereby allowing 1 easy to use system. Data obtained from and SHIP-1 reintroduction have revealed that chromosome SHIP-1 not only acts as a negative player PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 back to PtdIns(4,5)P2 [5], in T cell lines proliferation, but also and regulate critical pathways, such as NF-κB phosphatase-1 (SHIP-1), which hydrolyses activation, and also appear to remarkably the inhibit T cell apoptosis. On the other hand, phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-triphosphate experiments using primary T cells from (PtdIns(3,4,5)P3) SHIP-1-/- mice have highlighted a new role tetrakisphosphate (InsP4) [6]. SHIP-1, a for cell 145 kDa protein expressed in hemopoietic development, but also emphasize that this cells, contains a central phosphatase protein domain, an N-terminal SH2 domain and a SHIP-1 is in not regulatory required for T T cell tensin by homologue 10), deleted which SH2-containing 5-phosphates and hydrolyses inositol-5- from inositol-1,3,4,5- proliferation. In support of these results, C-terminal SHIP-1-/- lymphopenic, phosphorylable NPXY sites and proline- suggesting that SHIP-1 function in T cells rich sequences (Figure 1) [7]. SH2 domain differs from its role in the myeloid lineage. and NPXY sites mediate the binding of mice are domain on containing SHIP-1 with a series of consensus motifs or adapter proteins, like immunoreceptor INTRODUCTION The PI3K pathway regulates many signalling motifs (ITIM and ITAM) and important cellular functions, such as various Doks [8, 9]. Through its inositol survival, proliferation, cell activation and phosphatase activity, SHIP-1 influences migration [1-3]. Upon activation, PI3K PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 levels in many cell types, generates phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5- which has a crucial impact in the negative triphosphate (PtdIns(3,4,5)P3) from regulation of cellular proliferation and PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 attracts apoptosis. In support of this, SHIP-1-/- PtdIns(4,5)P2. pleckstrin homology containing proteins (PH) domain- mice have an increased number of myeloid plasma cells due to enhanced survival and membrane, which allows their activation proliferation of their progenitors, thereby and subsequent signalling. PH domain- resulting in splenomegaly and myeloid containing proteins include notably Akt, a infiltration in various organs, including key messenger in cellular proliferation and lungs [10, 11]. protection from apoptosis [4]. exhibit to the The SHIP-1-/- myeloid cells furthermore decreased negative regulation of the PI3K pathway is susceptibility to apoptotic cell death, an achieved notably by PTEN (phosphatase observation that has to be linked to the 2 constitutive Akt activation in these cells, of B cell development. leading mechanisms underlying SHIP-1-mediated to enhanced survival and The molecular A SHIP-1 SH2 Proline-rich Phosphatase domain NPXY NPXY B PI3K PtdIns(4,5)P2 PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 SHIP-1 PtdIns(3,4)P2 PTEN Akt, Btk, … Figure 1. A. Structure of the SHIP-1 protein. B. Through its lipid phosphatase activity, SHIP-1 dephosphorylates PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 to PtdIns(3,4,)P2, thereby negatively regulating the PI3K pathway. PTEN exerts the same function, but catalyzes PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 back into PtdIns(4,5)P2. See text for details. proliferation [11]. This observation is inhibition of B cell proliferation are now reinforced by the demonstration that a well understood. dominant-negative induced by BCR activation are inhibited by mutation reducing Signalling pathways catalytic activity of SHIP-1 was found to co-aggregation be FcγRIIB, a low affinity Fc receptor. This associated with acute myeloid leukaemia [12]. SHIP-1 also acts at different levels co-aggregation containing between occurs immune BCR when complexes and IgGbind in B cell biology. SHIP-1-/- mice exhibit a simultaneously the BCR and FcγRIIB and reduction in the number of pre-B and trigger tyrosine phosphorylation within immature B cells in the bone marrow, but immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibitory increased number of hypermature B cells motifs (ITIM) of the cytoplasmic tail of in the spleen. B cells from SHIP-1-/- mice FcγRIIB [17]. are also hypersensitive to BCR stimulation, induces the recruitment of SHIP-1 to the but less sensitive to apoptosis [10, 13-16]. tyrosine phosphorylated ITIM of FcγRIIB These data reflect that the inhibitory via its SH2 domain. signals mediated by SHIP-1 have positive dephosphorylates PtdIns(3,4,5)P3, leading or negative impacts depending on the stage to inhibition of PLCγ, Akt and Btk, thereby This phosphorylation SHIP-1 then 3 inhibiting calcium expression [29-31] has opened up new mobilisation ([18-20] and [13] for review). possibilities for studying SHIP-1 biological functions FcγRIIB- role in T cells by complementation mediated inhibitory signals upon FcεR1- experiments. Because of their deficiency induced degranulation in mast cells ([21- in SHIP-1 expression, Jurkat cells express 23] and [9] for review). a very high level of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 and a SHIP-1 proliferation also and in subsequent constitutive Akt activation ROLE OF SHIP-1 IN T compared to other leukemic cell lines LYMPHOCYTES (such as CEM, MOLT-4 or HUT78) or human PBLs [32]. Restoration of SHIP-1 activity in Jurkat cells was first carried out Data obtained from T cell lines Although the role of SHIP-1 has using a Tet-Off regulated system encoding been intensely studied in myeloid and B the lipid phosphatase core of SHIP-1 fused cells, its exact biological function in T to the transmembrane region of rat CD2. cells remains poorly understood. Pioneer Expression of this membrane-localized works tyrosine SHIP-1 in Jurkat was sufficient to reduce phosphorylation of SHIP-1 upon CD3 and Akt constitutive activation and the activity CD28 stimulation, and redistribution of its of downstream PI3K effector, constituting catalytic activity at the plasma membrane the first evidence that SHIP-1 is capable of [24, 25], without highlighting a clear modulating important signalling pathways biological role of SHIP-1 in the regulation in T cells [32]. Ectopic expression of the of T cell activation. complete have demonstrated a SHIP-1 was also SHIP-1 protein was also reported to interact with the ξ chain of the achieved in Jurkat cells by Horn et al. TCR, at least in vitro [26]. An embryonic SHIP-1 expressing Jurkat cells have work has also demonstrated that FcγRIIB reduced PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 level compared to co-aggregation with the TCR results in the tyrosine SHIP-1, diminution of Akt phosphorylation on indicating that, like in B cells, SHIP-1 S473 and T308. Phosphorylation of GSK- would be responsible for FcγRIIB-elicited 3β, an Akt substrate, is also down inhibitory signalling in T cells [27]. regulated upon SHIP-1 reexpression [33]. Finally, SHIP-1 was demonstrated to play Interestingly, expression of SHIP-1 in a role in LFA-1-dependent adhesion [28]. Jurkat also reduces cellular proliferation, phosphorylation of parental clone, and subsequent The finding that the Jurkat T cell notably by affecting the G1 cell cycle line was defective in SHIP-1 (and PTEN) regulators Rb and p27Kip1 [33] and KLF2, a 4 factor implicated in T cell quiescence [34]. pathway [38]. Importantly, we have also Altogether, reintroduction shown that Jurkat expressing SHIP-1 are experiments have highlighted a role for much more resistant to H2O2 and FasL- SHIP-1 in negatively regulating T cell induced apoptosis than the parental cells lines proliferation. In support of this, ([38] and manuscript under preparation). down-regulation of SHIP-1 expression has This result may appear discrepant with been described in adult T cell leukaemia previous data obtained with other cell (ATLL) [35]. types proposing that SHIP-1 increases these Using a lentiviral system, we have apoptosis by antagonising the anti- also express SHIP-1 in Jurkat cells and apoptotic function of PI3K. have furthermore positioned this protein as proapoptotic role of SHIP-1 was described a key adaptor in the activation of NF-κB in several cell types, including B, myeloid upon oxidative stress. After exposure to and erythroid cells [11, 14, 39-41]. On the H2O2, parental Jurkat cells activate NF-κB contrary, some authors have reported that through phosphorylation of the inhibitor SHIP-1 recruitment attenuates B cell IκBα on Y42, which triggers its calpain- apoptosis mediated degradation and allows the freed independently of BCR coligation, and that NF-κB to migrate into the nucleus [36, 37]. failure to recruit SHIP-1 increases the On the contrary, Jurkat expressing SHIP-1 apoptotic activate NF-κB through IκB Kinase (IKK) Furthermore, it is worth noting that SHIP-1 activation and phosphorylation of the deficient mice are lymphopenic [10, 11, inhibitor IκBα on S32 and 36 upon H2O2 44], suggesting that, depending on the cell- stimulation. Cell lines that express SHIP-1 type and the biological context, SHIP-1 naturally (i.e. CEM or the subclone Jurkat can exert either pro- or anti-apoptotic JR) also follow the same signalling functions (Table I). induced Indeed, a by phenotype FcγRIIB [42, Cell type Apoptosis inducer Role of SHIP-1 References Myeloid cells Sorbitol, Pro-apoptotic [11, 40] 43]. cycloheximide, anisomycin A, antiFas antibody, TNF-α Erythroid cells EPO deprivation Pro-apoptotic [39] B cells Aggregation of the Pro-apoptotic [14] 5 BCR Activin/TGF-β Pro-apoptotic [41] Clustering of Anti-apoptotic [42] Anti-apoptotic [38] FcγRIIB independently of BCR coligation T cells H2O2 Table I: Pro- or anti-apoptotic role of SHIP-1 in different hemopoietic cells and biological conditions. number of CD4- and CD8- double negative cells [44]. On the other hand, there is a Data obtained from primary T cells As described above, generation of reduced number of T cells in the spleen SHIP-1 deficient mice have considerably from SHIP-1 KO mice, due to a severe increased reduction of CD8+ T cells, suggesting that our understanding of its biological role. These mice have notably SHIP-1 revealed that SHIP-1 does not function CD4+/CD8+ ratio in the periphery. But the similarly in the lymphoid than in the most intriguing feature of CD4+ T cells myeloid lineage. Indeed, whereas SHIP-1 from SHIP-1 KO mice is that they are KO mice have more myeloid cells than wt phenotypically and functionally regulatory mice, they exhibit a reduction in the T cell T cells (Tregs) [44]. population [10, 11]. An elegant study cells from SHIP-1 KO mice are activated, carried out by the Rothman’s group but do not respond to TCR stimulation or recently addressed SHIP-1’s role in is important in maintaining Indeed, splenic T produce cytokines in response to PMA primary mouse T cells [44]. These authors stimulation. They exhibit furthermore have demonstrated that, like in B cells, Tregs markers (such as high TGFβ SHIP-1 appears to play a biphasic role in T production and expression of the transcription factor Foxp3) and are able to cell physiology. First, SHIP-1, together suppress IL-2 production by CD4+ CD25- with the adapter protein Dok-1, plays a key T cells upon CD3 stimulation. role in T cell development, since mice from mice deficient for both SHIP-1 and deficient for both SHIP-1 and Dok-1 Dok-1 exhibit an important reduction in the highlighting the crucial role of the adaptor percentage of CD4+ and CD8+ double Dok-1 for SHIP-1 activity [44]. positive, analogous cooperation of Dok-1 with together with an increased share the same T cells phenotype, An 6 SHIP-1 has already been demonstrated in under certain conditions, in B cells, it FcγRIIB signalling in B cells, where SHIP- appears to play an anti-apoptotic role in T 1 serves as an adaptor protein to recruit cell lines. iii) Moreover, the fact that T Dok-1 to the receptor, which in turn, cell specifc loss of PTEN produces some inhibits the Ras/MAPK pathway [45]. opposite phenotypes to SHIP-1 KO (i.e. T Altogether, these data prompt us to cells hyperproliferation) suggests that the conclude that SHIP-1 functions differently signalling role of SHIP-1 in T cells is not in T cells than in myeloid or B cells for at restricted to its lipid phosphatase activity least three reasons: i) SHIP-1 does not with respect to PtdIns(3,4,5)P3, seem to inhibit T cells proliferation (at common substrate of the two enzymes least primary T cells), but instead its [46]. absence opposite creates an anergy to TCR stimulation. ii) Whereas SHIP-1 is clearly the The mechanisms underlying these roles investigation are in currently our under laboratory. a pro-apoptotic protein in myeloid and, AKNOWLEDGEMENTS 5 This work was supported by grants from the Belgian National Fund for Scientific Research (FNRS, Brussels, Belgium), the Interuniversity Attraction Pole (IAP5/12, 6 Brussels, Belgium), and the ARC program (ULG 04/09-323, Belgium). GG is a PhD student from the Télévie program (FNRS, 7 Belgium), EC is supported by the FRIA (FNRS, Brussels) and JP is Research 8 Director from the FNRS. REFERENCES 1 2 3 4 Krystal, G. (2000) Semin Immunol 12, 397-403 Ward, S. G. (2006) Trends Immunol 27, 80-7 Ward, S. G. and Cantrell, D. A. (2001) Curr Opin Immunol 13, 332-8 Abraham, E. (2005) Crit Care Med 33, S420-2 9 10 Stambolic, V., Suzuki, A., de la Pompa, J. L., Brothers, G. M., Mirtsos, C., Sasaki, T., Ruland, J., Penninger, J. M., Siderovski, D. P. and Mak, T. W. (1998) Cell 95, 2939 Damen, J. E., Liu, L., Rosten, P., Humphries, R. K., Jefferson, A. B., Majerus, P. W. and Krystal, G. (1996) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93, 1689-93 Backers, K., Blero, D., Paternotte, N., Zhang, J. and Erneux, C. (2003) Adv Enzyme Regul 43, 15-28 Pesesse, X., Backers, K., Moreau, C., Zhang, J., Blero, D., Paternotte, N. and Erneux, C. (2006) Adv Enzyme Regul Rauh, M. J., Kalesnikoff, J., Hughes, M., Sly, L., Lam, V. and Krystal, G. (2003) Biochem Soc Trans 31, 286-91 Helgason, C. D., Damen, J. E., Rosten, P., Grewal, R., Sorensen, P., Chappel, S. M., Borowski, A., Jirik, F., Krystal, G. and Humphries, R. K. (1998) Genes Dev 12, 1610-20 7 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Liu, Q., Sasaki, T., Kozieradzki, I., Wakeham, A., Itie, A., Dumont, D. J. and Penninger, J. M. (1999) Genes Dev 13, 786-91 Luo, J. M., Yoshida, H., Komura, S., Ohishi, N., Pan, L., Shigeno, K., Hanamura, I., Miura, K., Iida, S., Ueda, R., Naoe, T., Akao, Y., Ohno, R. and Ohnishi, K. (2003) Leukemia 17, 1-8 Brauweiler, A. M., Tamir, I. and Cambier, J. C. (2000) Immunol Rev 176, 69-74 Brauweiler, A., Tamir, I., Dal Porto, J., Benschop, R. J., Helgason, C. D., Humphries, R. K., Freed, J. H. and Cambier, J. C. (2000) J Exp Med 191, 1545-54 Helgason, C. D., Kalberer, C. P., Damen, J. E., Chappel, S. M., Pineault, N., Krystal, G. and Humphries, R. K. (2000) J Exp Med 191, 781-94 Liu, Q., Oliveira-Dos-Santos, A. J., Mariathasan, S., Bouchard, D., Jones, J., Sarao, R., Kozieradzki, I., Ohashi, P. S., Penninger, J. M. and Dumont, D. J. (1998) J Exp Med 188, 1333-42 Muta, T., Kurosaki, T., Misulovin, Z., Sanchez, M., Nussenzweig, M. C. and Ravetch, J. V. (1994) Nature 369, 340 Scharenberg, A. M., El-Hillal, O., Fruman, D. A., Beitz, L. O., Li, Z., Lin, S., Gout, I., Cantley, L. C., Rawlings, D. J. and Kinet, J. P. (1998) Embo J 17, 1961-72 Aman, M. J., Lamkin, T. D., Okada, H., Kurosaki, T. and Ravichandran, K. S. (1998) J Biol Chem 273, 33922-8 Bolland, S., Pearse, R. N., Kurosaki, T. and Ravetch, J. V. (1998) Immunity 8, 509-16 Ono, M., Bolland, S., Tempst, P. and Ravetch, J. V. (1996) Nature 383, 263-6 Huber, M., Helgason, C. D., Damen, J. E., Liu, L., Humphries, 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 R. K. and Krystal, G. (1998) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95, 11330-5 Gimborn, K., Lessmann, E., Kuppig, S., Krystal, G. and Huber, M. (2005) J Immunol 174, 507-16 Lamkin, T. D., Walk, S. F., Liu, L., Damen, J. E., Krystal, G. and Ravichandran, K. S. (1997) J Biol Chem 272, 10396-401 Edmunds, C., Parry, R. V., Burgess, S. J., Reaves, B. and Ward, S. G. (1999) Eur J Immunol 29, 3507-15 Osborne, M. A., Zenner, G., Lubinus, M., Zhang, X., Songyang, Z., Cantley, L. C., Majerus, P., Burn, P. and Kochan, J. P. (1996) J Biol Chem 271, 29271-8 Jensen, W. A., Marschner, S., Ott, V. L. and Cambier, J. C. (2001) Biochem Soc Trans 29, 840-6 Mazerolles, F., Barbat, C., Trucy, M., Kolanus, W. and Fischer, A. (2002) J Biol Chem 277, 1276-83 Bruyns, C., Pesesse, X., Moreau, C., Blero, D. and Erneux, C. (1999) Biol Chem 380, 969-74 Sakai, A., Thieblemont, C., Wellmann, A., Jaffe, E. S. and Raffeld, M. (1998) Blood 92, 34105 Astoul, E., Edmunds, C., Cantrell, D. A. and Ward, S. G. (2001) Trends Immunol 22, 490-6 Freeburn, R. W., Wright, K. L., Burgess, S. J., Astoul, E., Cantrell, D. A. and Ward, S. G. (2002) J Immunol 169, 5441-50 Horn, S., Endl, E., Fehse, B., Weck, M. M., Mayr, G. W. and Jucker, M. (2004) Leukemia 18, 1839-49 Garcia-Palma, L., Horn, S., Haag, F., Diessenbacher, P., Streichert, T., Mayr, G. W. and Jucker, M. (2005) Br J Haematol 131, 628-31 Fukuda, R., Hayashi, A., Utsunomiya, A., Nukada, Y., Fukui, R., Itoh, K., Tezuka, K., Ohashi, K., Mizuno, K., Sakamoto, 8 36 37 38 39 40 41 M., Hamanoue, M. and Tsuji, T. (2005) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102, 15213-8 Takada, Y., Mukhopadhyay, A., Kundu, G. C., Mahabeleshwar, G. H., Singh, S. and Aggarwal, B. B. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 2423324241 Schoonbroodt, S., Ferreira, V., Best-Belpomme, M., Boelaert, J. R., Legrand-Poels, S., Korner, M. and Piette, J. (2000) J Immunol 164, 4292-300 Gloire, G., Charlier, E., Rahmouni, S., Volanti, C., Chariot, A., Erneux, C. and Piette, J. (2006) Oncogene Boer, A. K., Drayer, A. L. and Vellenga, E. (2001) Leukemia 15, 1750-7 Gardai, S., Whitlock, B. B., Helgason, C., Ambruso, D., Fadok, V., Bratton, D. and Henson, P. M. (2002) J Biol Chem 277, 5236-46 Valderrama-Carvajal, H., Cocolakis, E., Lacerte, A., Lee, E. H., Krystal, G., Ali, S. and Lebrun, J. J. (2002) Nat Cell Biol 4, 963-9 42 43 44 45 46 Pearse, R. N., Kawabe, T., Bolland, S., Guinamard, R., Kurosaki, T. and Ravetch, J. V. (1999) Immunity 10, 753-60 Ono, M., Okada, H., Bolland, S., Yanagi, S., Kurosaki, T. and Ravetch, J. V. (1997) Cell 90, 293301 Kashiwada, M., Cattoretti, G., McKeag, L., Rouse, T., Showalter, B. M., Al-Alem, U., Niki, M., Pandolfi, P. P., Field, E. H. and Rothman, P. B. (2006) J Immunol 176, 3958-65 Tamir, I., Stolpa, J. C., Helgason, C. D., Nakamura, K., Bruhns, P., Daeron, M. and Cambier, J. C. (2000) Immunity 12, 347-58 Suzuki, A., Yamaguchi, M. T., Ohteki, T., Sasaki, T., Kaisho, T., Kimura, Y., Yoshida, R., Wakeham, A., Higuchi, T., Fukumoto, M., Tsubata, T., Ohashi, P. S., Koyasu, S., Penninger, J. M., Nakano, T. and Mak, T. W. (2001) Immunity 14, 523-34 9

![Historical_politcal_background_(intro)[1]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005222460_1-479b8dcb7799e13bea2e28f4fa4bf82a-300x300.png)