Just Another Mississippi Whitewash by Jack E

advertisement

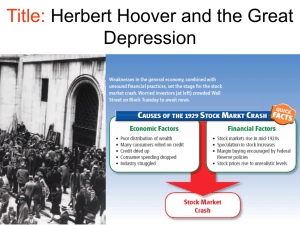

Just Another Mississippi Whitewash by Jack E. White Time, January 9, 1989 p. 60. Here we go again. Exploiting white America's ignorance of historic racial oppression, Hollywood casts a spotlight on the rich but neglected story of the black struggle for equal rights. As has happened with every popular work on the subject, from Uncle Tom's Cabin to Roots, Mississippi Burning evokes a gasp of horrified discovery from many whites who act as if they are learning about the viciousness of slavery and segregation for the very first time. Unfortunately, the film does little to deepen the knowledge of its audience. Though its producers say the movie is fictional, they so artfully commingle fact and invention that many viewers, whose ability to discern a whopper when they see one has been obliterated by an age of TV docudramas, are convinced of its veracity. They leave the theater believing a version of history so distorted that it amounts to a cinematic lynching of the truth. From its opening sequence, Burning convincingly recaptures the racial dread of 1964 Mississippi. But the verisimilitude is soon sacrificed for a bogus conclusion: that to protect the rights of blacks, the Federal Government sank to the same level of lawless terror occupied by the Ku Klux Klan. To the extent they appear at all, blacks are portrayed as ineffectual victims, helplessly waiting for the "Kennedy boys" to set them free. In due course, that is just what happens, as the FBI cracks the case by brutally intimidating a white witness. Not much of this is within spitting distance of what really occurred. Even the little details in the film -- such as placing James Chaney, a black thoroughly familiar with the terrifying back roads of Neshoba County, in the backseat of the station wagon he was actually driving -relegate blacks to the background of the drama of which they were the real-life heroes. One gets no sense of their courageous struggle against violent white supremacy and second-class citizenship. Even more twisted is the film's depiction of an FBI so zealous in its defense of black rights that it would resort to vigilantism to promote them. That contention is laughable to civil rights veterans of the early 1960s, who pleaded with the bureau to take a more active role in protecting blacks. Only two weeks before the murders, a delegation of Mississippi activists journeyed to Washington to implore federal officials to protect the civil rights workers who were flocking into the state for the Freedom Summer. Yet despite repeated appeals to the FBI and Justice Department on the night the three civil rights workers disappeared, nearby agents did not arrive in Philadelphia until the next day. By then it was too late. Only after the murders provoked a national outcry did the FBI enter Mississippi in force and begin a massive effort to undermine the Klan. Until then Director J. Edgar Hoover's insistence that the bureau was a strictly investigative agency forced FBI agents to invest far more energy in busting stolen car rings and foiling bank robberies than in probing even the most flagrant depredations against blacks. In 1961 the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights suggested that since the bureau was often so closely linked to Southern law-enforcement officials, another group might take over the handling of civil rights cases. Justice Department prosecutors became so dissatisfied with the bureau's lethargic performance in voting-rights cases that they concocted "coaching" memos that spelled out exactly which questions should be asked of exactly which witness in civil rights investigations. Only by boxing in the agents in that way could the lawyers be sure the FBI would gather the evidence needed to file discrimination suits. The truth is that Hoover loathed blacks and detested their leaders, and so did many of his men. According to an agent quoted by Hoover's biographer Richard Gid Powers, during the early '60s "in about 90% of the situations in which bureau personnel referred to Negroes, the word `nigger' was used." Until 1962 there were only five black FBI agents: Hoover's chauffeurs, houseboy and messenger. During the period dealt with in Burning, Hoover's bureau was indeed engaged in a lawless campaign against an enemy. But its target was Martin Luther King Jr. It began with wiretaps and buggings, approved by then Attorney General Robert Kennedy, aimed at digging up proof that King was under the influence of suspected Communists. The surveillance yielded plenty about King's extramarital affairs, which Hoover circulated among high government officials and journalists. In his important study of the civil rights movement, Parting the Waters, Taylor Branch writes that by 1963 Hoover was so convinced King was a danger to America that the bureau no longer alerted him to death threats. In late 1964 FBI agents mailed a threatening letter and tape recording of King's sexual escapades to his wife, apparently in hopes that the revelation would drive him to suicide. None of these facts are in dispute or particularly difficult to come by, but the makers of Mississippi Burning, in their pursuit of a box-office smash, chose to ignore them. In the process, they have not only turned history inside out but have also lent support to a racist myth. Says Seth Cagin, co-author of We Are Not Afraid, a rigorous account of the Philadelphia murders: "The film suits the fantasy of the Ku Klux Klan that the FBI was an invading tyrannical force that imposed its will on the South because it played dirty." It is bad enough that most Americans know next to nothing about the true story of the civil rights movement. It would be even worse for them to embrace the fabrications in Mississippi Burning.