Headache Resource - Swansea Acute GP Services homepage

advertisement

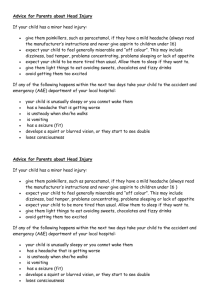

Swansea Minor Injuries and Ambulatory Care Unit-Acute GP Unit GP referrals with acute presenting complaint of “Headaches” Prepared by:Dr Chris Johns http://www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/sign107.pdf Headaches generally fit into 5 categories When assessing the person with a headache emergency, it is important to realise that there are about 5 different categories of headache that present as an emergency. 1. Thunderclap Headache (SAH until proved otherwise) 2. Headache and Fever 3. Headache with Focal Neurology (Visual symptoms, Numbness, Speech difficulty, Weakness, Vertigo, Epileptic Seizures,Confusion) 4. New Onset Persistent Headache 5. A Previous Headache Disorder that is difficult to control-almost always migrainous Headache is common, with a lifetime prevalence of over 90% of the general population in the United Kingdom (UK). It accounts for 4.4% of consultations in primary care2 and 30% of neurology outpatient consultations. Primary headaches are best treated by the GP and referral to the Acute GP unit should be for those will a history suggestive of secondary (caused by another condition) headache. See above highlighted in red Symptoms Patients who present with a pattern of recurrent episodes of severe disabling headache associated with nausea and sensitivity to light, and who have a normal neurological examination, should be considered to have migraine. Patients who present with headache and red flag features for potential secondary headache should be referred to a specialist appropriate to their symptoms for further assessment. Patients with a first presentation of thunderclap headache should be referred immediately to hospital for same day specialist assessment. Giant cell arteritis should be considered in any patient over the age of 50 presenting with a new headache or change in headache. Investigation Neuro-imaging is not indicated in patients with a clear history of migraine, without red flag features for potential secondary headache, and a normal neurological examination. In patients with thunderclap headache, unenhanced CT of the brain should be performed as soon as possible and preferably within 12 hours of onset. Patients with thunderclap headache and a normal CT should have a lumbar puncture. Secondary Headache Secondary headache (ie headache caused by another condition) should be considered in patients presenting with new onset headache or headache that differs from their usual headache. Observational studies have highlighted the following warning signs or red flags for potential secondary headache which requires further investigation: Red flag features: new onset or change in headache in patients who are aged over 50 thunderclap: rapid time to peak headache intensity (seconds to 5 mins) new history of cancer focal neurological symptoms (eg limb weakness, aura <5 min or >1 hr) non-focal neurological symptoms (eg cognitive disturbance) change in headache frequency, characteristics or associated symptoms abnormal neurological examination headache that changes with posture headache wakening the patient up (NB migraine is the most frequent cause of morning headache) headache precipitated by physical exertion or valsalva manoeuvre (eg coughing, laughing, straining) patients with risk factors for cerebral venous sinus thrombosis jaw claudication or visual disturbance neck stiffness fever new onset headache in a patient with a history of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection Diagnosis and management Neuroimaging is not indicated in patients with a clear history of migraine, without red flag features for potential secondary headache, and a normal neurological examination. Clinicians requesting neuroimaging should be aware that both MRI and CT can identify incidental neurological abnormalities which may result in patient anxiety as well as practical and ethical dilemmas with regard to management. Brain CT should be performed in patients with headache who have unexplained abnormal neurological signs, unless the clinical history suggests MRI is indicated. CT scanning alone is not enough to rule out SAH-lumbar puncture is required. No evidence has been identified on the benefits of routine full blood count assessment or the use of X-ray of the cervical spine in the diagnosis of patients with headache. When SAH is suspected, CT brain scan should be carried out as soon as possible to maximise sensitivity. Sensitivity of CT for subarachnoid haemorrhage is 98% at 12 hours dropping to 93% by 24 hours. Acute GP Unit triage and assessment Take a history of the headache pattern from the GP and categorise into one of 5 groups A Previous Headache Disorder that is difficult to control group. If the headache is likely to be primary (including migraine) encourage the GP to manage the problem in Primary Care including the option for urgent GP generated CT scanning or neurology OPD assessment. If the history is “classic” SAH (thunderclap with/without neurological signs refer direct to SAU as will need both CT scan and lumbar puncture. New Onset Persistent Headache If history is very suggestive of GCA advise referral to Rapid Access Eye Clinic. If GCA possible and no ESR see in AGPU and organise acute investigation and referral if required. New Onset Persistent Headache If history suggestive of secondary cause then see and assess in AGPU. Organise investigation (CT scan) if required. Urgent referral to neurological OPD slot also an option. Headache and Fever If the history of a headache with fever some of these patients and it is very dependent on the history and examination from the GP may be appropriate for AGPU assessment. However if bacterial meningitis is very likely then direct referral to SAU is appropriate. Headache with Focal Neurology (Visual symptoms, Numbness, Speech difficulty, Weakness, Vertigo, Epileptic Seizures, Confusion). Some of these patients if their symptoms are transient may need referral to TIA pathway via GP. If other red flags most will need referral to SAU. Headache with a fever Causes o o o o o o Systemic Illness Headache (including viral headache) Viral Meningitis Acute Sinusitis Bacterial Meningitis Cerebral Abscess Viral Encephalitis Bacterial meningitis in adults - clinical presentation Features of meningitis: fever nausea/vomiting malaise headache neck stiffness (absent in 30% of cases) photophobia lethargy drowsiness, confusion, impaired consciousness seizures - late sign positive Kernig's and Brudzinski's signs raised intracranial pressure (ICP) - late sign Glasgow Coma score less than 8 dilating, unequal, or poorly reacting pupils irritability Symptoms suggestive of bacterial meningitis will always require assessment in SAU Viral meningitis may be clinically indistinguishable from bacterial meningitis but features may be more mild and complications (e.g. focal neurological deficits) less frequent. Any person presenting with suspected meningitis should therefore be managed as having bacterial meningitis until proved otherwise. Individual symptoms have low diagnostic accuracy. Absence of fever, neck stiffness, and altered mental status makes the diagnosis of meningitis much less likely. Systemic illness headache About 25% of cases had a non-serious secondary headache associated with infection - so called systemic illness headache. The AGPU may been able to treat many of these will appropriate assessment, treatment and follow up beyond that of a normal GP. Additional Information on Headaches (CKS summary) Suspect a serious cause if a headache: Follows trauma to the head and the headache is progressive, and especially if o it is associated with impaired consciousness and/or a focal neurological deficit. If this occurs, suspect an epidural or subdural haematoma. Is sudden, with a rapid time to peak headache intensity (that is, from a o few seconds to 5 minutes). If this occurs, suspect a subarachnoid haemorrhage. Develops simultaneously with a sudden onset of neurological o impairment of speech, sensation, power, or consciousness, especially if the impairment lasts longer than 1 hour. If this occurs, suspect a transient ischaemic attack or stroke (including subarachnoid haemorrhage). Is associated with fever and impaired consciousness, neck stiffness, or o photophobia. If this occurs, suspect an intracranial infection (such as meningitis or encephalitis). Is associated with tenderness over the temporal artery in a person older o than 50 years of age. If this occurs, suspect giant cell arteritis. Is associated with features indicating a high risk of a space occupying o lesion, including people with: o A new headache accompanied by features suggestive of raised intracranial pressure, including papilloedema, vomiting, posture-related headache, or headache waking them from sleep (unless it is clearly cluster headache). A new headache accompanied by focal neurological symptoms, or non- o focal neurological symptoms such as blackout, change in personality or memory. o An unexplained headache that becomes progressively severe. o An unexplained headache in anyone previously diagnosed with cancer. o A new-onset of epileptic seizures. Is associated with features indicating a moderate risk of a space o occupying lesion, including people with: A new headache, when a diagnostic headache pattern has not emerged o after 8 weeks. A new headache, in a person older than 50 years of age. o Is associated with severe unilateral eye pain, red eye, fixed and dilated o pupil, hazy cornea, or diminished vision. If this occurs, suspect acute glaucoma. Is associated with nausea and impaired concentration in a person o exposed to a potential carbon monoxide source, including smoke, engine exhausts, or gases from gas or solid fuel appliances retained in an enclosed space. Severe poisoning can cause impaired consciousness, chest pain, and a wide range of neurological deficits. If symptoms of a serious cause of headache are excluded assess for medicationoveruse and other secondary causes of headache. Exclude symptoms of serious secondary causes of headache, before considering other secondary causes. Suspect medication-overuse headache (MOH) in people with tension-type headache (TTH) or migraine, when they experience a chronic headache (headache on more than 15 days a month) that develops or worsens with frequent use of any pain relief medication. o MOH can occur with frequent use of any symptomatic treatment for acute headache. Typically, it develops with drug treatment of episodic migraine or TTH, but may occur in people with migraine or TTH who take analgesics for other painful conditions. o The symptoms of MOH resemble chronic TTH or chronic migraine; people overusing triptans are more likely to have migraine-like symptoms. o MOH resolves following withdrawal of symptomatic treatment. This may result in complete resolution of the headache or leave the person with their original episodic migraine or TTH. Suspect other secondary causes when headache is associated with: o Caffeine withdrawal, in people consuming frequent caffeinated drinks such as tea, coffee, or colas. o Medications known to cause headache, such as nitrates and calcium channel blockers. o Pain that is localized to structures in the head and neck (such as the eyes, ears, sinuses, temporomandibular joint, teeth, or neck) indicative of conditions such as acute otitis media and sinusitis. o Fever or general malaise and evidence of systemic infection. o Head or facial pain in the area of a herpetic eruption. If symptoms of a secondary cause of headache have been excluded, consider a diagnosis of tension-type headache or migraine (common primary causes of headache).